“We Were Still the Little Band From Texas, Interpreters of That Great American Art Form the Blues”: Billy Gibbons on the Making of “Gimme All Your Lovin’”

How ZZ Top’s 1983 classic took the blues “up a notch”

ZZ Top’s Eliminator album was tracked in 1982 against a backdrop of synthesizer-infused rock music.

As the popularity of electronic instruments boomed and studio technology continued to move forward, music makers naturally changed with the times – and Billy Gibbons was no exception.

The band’s most commercially successful album, 1983’s Eliminator, was famously recorded using drum machines and synths.

Furthermore, the ZZ Top frontman’s classic Les Paul/Marshall rig had been put to one side in place of a Dean Z electric guitar and Legend 50 amp.

Here, Gibbons explains how “the little band from Texas” continued to enthral audiences in a rapidly evolving music scene with their unique interpretation of the blues.

Your tone on "Gimme All Your Lovin'," and the Eliminator record in general, is great. But at this time your setup was pretty far from Pearly Gates through a Marshall. You were using a Dean Z guitar and a Legend amp.

We liked what Dean was doing back in the day

Billy Gibbons

Back then, Frank Beard, our fearless drummer and the man with no beard, he had put together a nice recording studio, and he had a houseguest, Linden Hudson, who had previously worked as an engineer. And it was at Linden’s behest that we crank up and aim toward a little richer tone that the Eliminator sound came together.

We had gotten pretty handy with the cleanliness of Fender and that icy brilliance that Strats and Teles have. But we liked what Dean was doing back in the day.

And I had just taken delivery of an amplifier, the Legend 50, which was being made by a guy in Syracuse, New York. It was a hybrid solid-state and tube amp with a natural wood cabinet, and the sound was ferocious. It was sensational.

Famously, you used drum machines and synths in the recording of Eliminator. How did that affect the outcome of songs like “Gimme All Your Lovin’”?

A lot of the sounds coming over the airwaves were generated from drum machines

Billy Gibbons

It enhanced the focus on tuning and tempo. Tuning and timing became the goal. By this time, the sounds coming from the U.K. were getting so popular, and it was the British that really brought forward the elegance of timing into the recording scene.

Keep in mind, the economy in Britain was such that a lot of bands didn’t have the affordability to spend a lot of time in the studio. They didn’t have two weeks to get a sound on a snare drum or two weeks on a hi-hat. And so a lot of the sounds coming over the airwaves were generated from drum machines.

Hell, all you had to do was program the damn thing, plug it in and then you’re out of there. You’ve got your song done in 30 minutes. So we really became keen on those two elements – timing and tuning.

We’d get everything in good tune, and once the timing was tight, it opened up the space and allowed the rhythm changes to come together, and the whole thing was just tighter. It was a very magnetic and very appealing sound.

[Jim Dickinson] said to me, 'Man, you’ve taken the blues up a notch. Don’t change a thing!'

Billy Gibbons

Do you think that approach had an effect on the music’s stylistic direction?

As far as the effect on the writing, no, we were still the little band from Texas, interpreters of that great American art form the blues.

And I remember our good friend, the late [record producer and musician] Jim Dickinson, he was one of the resident house engineers [at Ardent Studios in Memphis, where Eliminator was recorded], and he was always around.

And he said to me, “Man, you’ve taken the blues up a notch. Don’t change a thing!” I took that as a high, high compliment.

Order ZZ Top's Eliminator here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

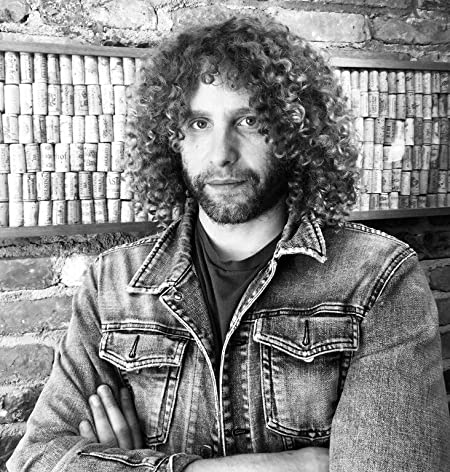

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue

"Get off the stage!" The time Carlos Santana picked a fight with Kiss bassist Gene Simmons and caused one of the guitar world's strangest feuds