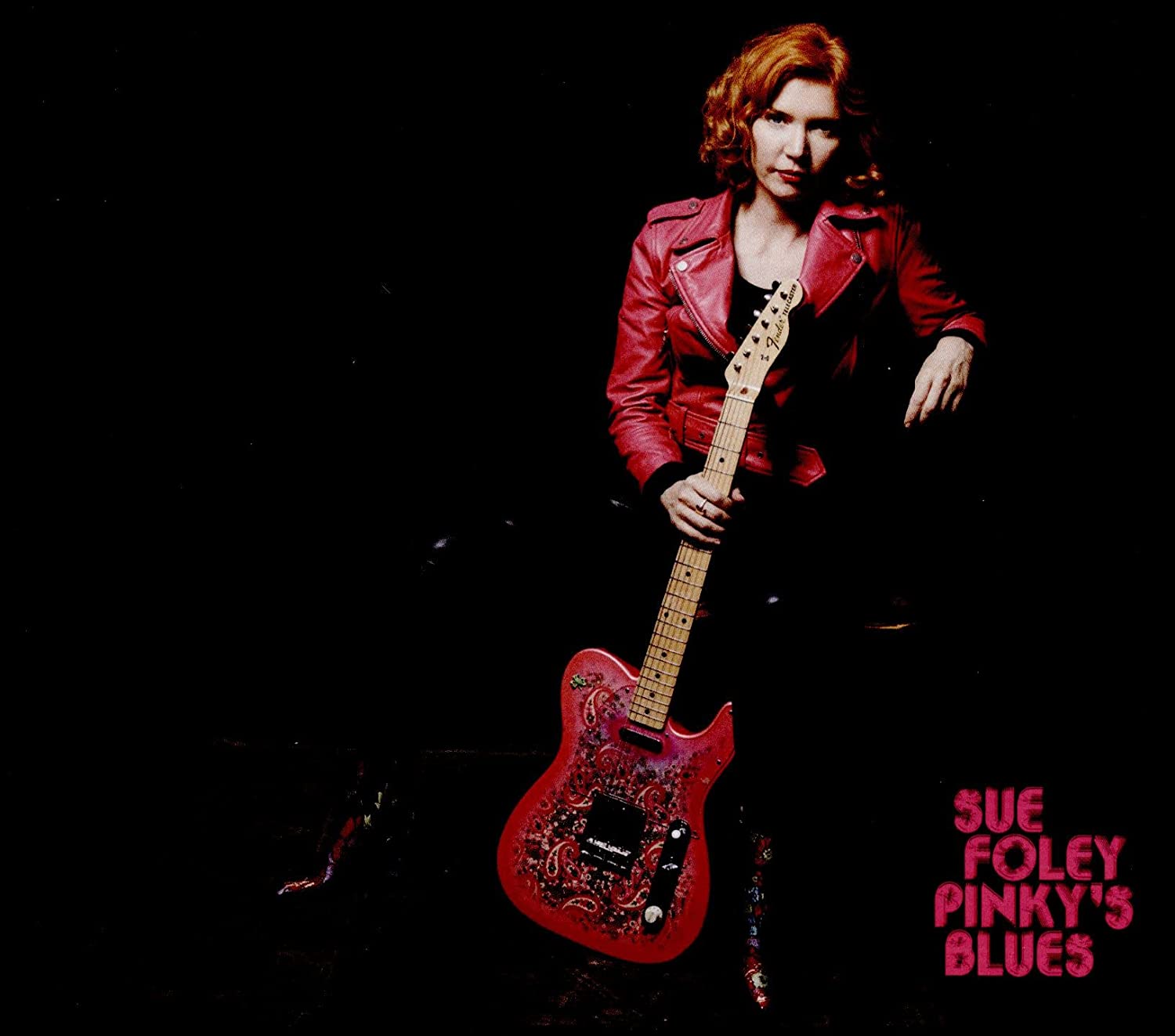

“Your Tone is Your Voice”: Sue Foley Returns with Ballsy Texas Blues Album

The Canadian guitarist brings swagger, sweetness and bite to the bold and unfiltered ‘Pinky’s Blues.’

Although Sue Foley is originally from Canada, on two major occasions her life has directed her to Texas. At the end of the ’80s, the guitarist and singer-songwriter moved to Austin when the city’s late blues impresario Clifford Antone signed her to his record label and became her mentor. The timing and location couldn’t have been more perfect for a 21-year-old blues guitarist building a career.

Right when Stevie Ray Vaughan was blowing the music world away and putting Austin on the map, Antone made sure Foley shared the stage with every national and local blues master who came through his eponymous club.

Playing three sets per night, six nights a week, Foley honed her chops and found her musical home and kindred spirits within the Texas blues community (one memorable off-stage moment involved shooting dice with Albert Collins).

Seeing her potential and dedication, Antone also ensured Foley went on the road to open for Buddy Guy, Koko Taylor and Johnny Winter.

Following her pregnancy and marriage, Foley returned to Canada to raise her son but continued touring and releasing a number of albums, always staying faithful to her love for traditional blues, even as she began studying flamenco guitar and incorporating some of those influences into her blues.

Then she was suddenly contacted by Mike Flanigin, a Hammond B3 player with Jimmie Vaughan and Billy Gibbons, and an old friend from her Austin days. The Antone’s club had re-opened, and Flanigin wanted her to come down and play. This led to them working together on Foley’s critically acclaimed 2018 album, The Ice Queen.

Anchored in Texas electric blues, yet musically varied with horns and acoustic solo numbers, the album featured duets with Gibbons, Vaughan and Charlie Sexton, and showcased Foley’s talent for writing blues songs and lyrics that avoid genre clichés.

It also showed that it’s fully possible to make a blues album with a modern approach and still win the Blues Foundation’s Koko Taylor Award for Best Female Traditional Blues Artist, which Foley did in 2020.

Riding a wave of success – including appearances with Vaughan at the Beacon Theater and Royal Albert Hall, and a packed calendar of festivals and international tours – Foley saw her performance schedule grind to a grim halt with the pandemic.

As a response to current circumstances and restrictions, she presents Pinky’s Blues with no overdubs and few guest musicians, capturing a heavyweight blues power trio with bassist John Penner, and drummer Chris Layton in electrifying interactions.

The result is a raw and unfiltered tribute to Texas blues and R&B. We spoke with Foley about the album after seeing her perform in Chicago with her trio, featuring Penner on bass and Corey Keller on drums.

You’ve followed up The Ice Queen with a straight-ahead Texas blues album. What made you go in this direction?

It was actually our producer, Mike Flanigin, who came up with the idea to make a blues guitar album. He produced The Ice Queen as well, and that was an artistic project that was really varied, where we were looking at each song individually and having different lineups of musicians. Then we did Mike’s album, West Texas Blues, which used the same group of players in the studio. So we decided to take the more stripped-down approach.

Since we were in the framework of not gathering in big groups, we knew it was going to be a small, close session, with just a few people spaced out in a big room, and that we had to do everything live with all of us playing together and in the moment.

The album sounds bold and ballsy, and your playing has the swagger to match.

Thank you. I listened to it recently to refresh my memory before touring, and I thought, Yeah, this sounds pretty greasy!

We were letting out a lot of energy, since we hadn’t been able to play live for a while

Sue Foley

But we were also just having fun. Whatever vibe you’re picking up from the studio, we were letting out a lot of energy, since we hadn’t been able to play live for a while. So there’s some lighthearted fun there too. We were just happy to hang out together.

There is some tender and lyrical R&B playing on it too, but the overall vibe is intense.

Well, we took a deep-dive into some really great songs, mostly the Texas blues catalog, with Clarence Gatemouth Brown [“Okie Dokie Stomp”], Frankie Lee Sims [“Boogie Real Low”] and Lavelle White [“Stop These Teardrops”], but also Chicago stuff like Robert Nighthawk [“Someday”] and Junior Wells [“When the Cat’s Gone the Mice Play”], and then my own songs [“Hurricane Girl,” “Dallas Man,” “Pinky’s Blues”]. When you play that kind of stuff, you’ve got to be really committed to it.

The title track is a slow instrumental blues. Two minutes into it, you do a very cool thing that almost sounds like sparks are coming out of your Tele. Is that just a backward rake?

It is, and it’s something Freddie King did a lot on songs like “San Ho Zay,” but he was using metal fingerpicks. I use a thumbpick and my fingers, but I have acrylic nails on my right-hand fingers, and those kind of act as fingerpicks.

Those have got to be hard to maintain?

They are. I try to keep them up, because I do a lot of Spanish nylon-string guitar playing at home, and sometimes on the road, too. I find that you can apply some of the Spanish fingerstyle techniques to a Fender Telecaster, they’re very compatible.

Why the Telecaster in particular? Is it because of its tonal clarity?

Yeah. Teles are very simple and pure. There’s just a tone and a volume knob, and all the nuances that you do in that framework are yours.

Teles can be tough taskmasters, too, since they don’t sustain as easily as a guitar with humbuckers.

Exactly. You’ve got to get used to playing pretty clean. I think if you can play a Tele well, it shows that you have good technique, because you have to play kind of precise and clean. There’s nowhere to hide.

I think if you can play a Tele well, it shows that you have good technique... There’s nowhere to hide

Sue Foley

How did Chris Layton’s presence behind the drum kit influence your playing?

A lot. When I talked about the album sounding greasy, that’s Chris. He’s just got that really deep pocket. When you’re playing with somebody that strong, you feel really supported, and they also help direct where a song’s gonna go. And you trust them, because you know that they know where it should go.

It’s not that Chris is telling me how to play; he’s directing things to where the groove is so deep that you’re comfortable, and it’s just going where it needs to go. He knows what’s happening, and he’s in the driver’s seat in a lot of ways.

But you like where he’s driving, so you don’t mind.

I love where he’s driving, and I think the drums on this album sound amazing, partially because of that big open room we were in.

How did you record the album?

We were set up just like we’d be onstage at a live gig, but with a few baffles between us, and a lot of room mics. The drums were in the middle, with the guitars and bass on each side, and the vocals were up in the middle.

[Engineer] Chris Bell was capturing all of it, so you’ll hear mic bleed, like guitar in the drum mics. And the bass was going through a mic’d amp, as opposed to going direct.

Where did you record?

Fire Station Studios in San Marcos, Texas. It’s the same place where I recorded The Ice Queen. It was all done in about two and a half to three days. What you’re hearing is all live, and mostly first or second takes. Vocals and guitars recorded at the same time. We couldn’t even overdub if we wanted to.

On the slow blues, “Say It’s Not So,” your vocals are very emotive. You’re completely connected to the lyrics, and you go into a wailing solo on the next beat. It takes a lot of live performing to reach that comfort level with music and lyrics, and on both instruments.

Singing was never what drove me. I wanted to play guitar, but I had to sing, and over time I learned to enjoy it. It is about doing a lot of gigs and pushing yourself, but I always stress that it’s also important who you listen to. It used to be pretty common for a guitar player to also be a great singer. Think of T-Bone Walker, or Freddie, B.B. and Albert King.

It is about doing a lot of gigs and pushing yourself, but I always stress that it’s also important who you listen to

Sue Foley

You also do a blazing version of Gatemouth’s “Okie Dokie Stomp.”

I’ve been playing it since I was in my early 20s. That song is a rite of passage in the blues guitar playing world, especially in Texas blues, but Hollywood Fats in California also did a famous version of it in Eb, where he adapted those horn lines to guitar.

Ronnie Earl’s version is insanely great too, and it’s in C, which is the same key I do it in, so I kind of reference Ronnie’s version, to be fair. It’s a fun song to get under your belt, like the Freddie King instrumentals. Back in the day, we had to know these songs.

Your rig is minimal, but the tone you get onstage and in the studio is full and rich. Let’s talk about that, starting with your signature guitar of many years.

Well, Pinky is a stock Fender Telecaster with the pink paisley design that was reissued in the mid-to-late ’80s, and I got it in 1987. They’re made in Japan, and for whatever reason, the Teles from that era are really good. I haven’t changed anything on it. I use the stock pickups. I’m afraid to change them, since I like the sound so much and I might not get it back.

I’ve had it refretted a few times. [Foley has three “Pinky” Telecasters, and her first is now off the road.] As for strings, I’ve used D’Addario [EXL 110] .010–.046 strings for probably 30 years. I change them every few gigs if we’re playing steady, since I like them kinda fresh.

On Pinky’s Blues, you use your original Fender Bassman that you’ve had for the past 30 years. Have you modded it in any way?

I don’t really mess with the speakers. It’s very rare that I change them. The only thing I change a lot is the [6L6] tubes. But, man, you can’t kill those Bassmans! They stand up on the road, night after night. It’s a simple workhorse of an amp, but if you get one in good shape, you can get a killer sound.

If the amp sound has a lot of body, like the Bassman, which has 40 loud watts, the 4x10s get the sound across with the right amount of power. You can drive the amp and speakers without getting as loud as the 2x12s on a Twin. It’s really versatile and will handle a small, medium or big stage. I find that you can get a full sound and get it to move around.

Sometimes when I play a smaller room, I’ll put the amp on its back, aiming it straight up. I learned that from Jimmie Vaughan

Sue Foley

How do you position the amp live?

It depends on the stage and the room. Sometimes when I play a smaller room, I’ll put the amp on its back, aiming it straight up. I learned that from Jimmie Vaughan. If you’re in a theater and you need the sound to be in the system too, you can baffle the amp to deflect the sound a bit, and if you’re on a big stage, like at a festival, you can have the two of them together and wide open.

You also don’t use pedals very much.

I do love reverb, so I use the Boss RV-5, and I also use some tremolo, like a Boss TR-2 or Strymon Flint, on a couple of tunes. Since the sound of a Telecaster is very clean and straight ahead, I sometimes use an Xotic RC clean boost, just to get sustain and widen the tone ever so much if I’m playing at a lower volume but still want to hear the pure tone. Cindy Cashdollar taught me that. But I literally keep the boost at the lowest possible setting. If I can drive the amp hard enough, I won’t use it. I like the sound out of the amp mostly.

You’ve got to create yourself and your tone, and then use the pedal, but a lot of times people go the opposite way. They use the pedal to create themselves

Sue Foley

Anybody can hide behind pedals. I don’t. You don’t want to lean on them too much or they’ll start to shape your tone when it really should come from the guitar, amp and your hands. You’ve got to create yourself and your tone, and then use the pedal, but a lot of times people go the opposite way. They use the pedal to create themselves. It’s backwards, and it’s so pedal-heavy that you can’t tell who that player is. So many players all sound the same – like the pedal.

Do you have any tips for improving tone?

I stress being picky about who you listen to, or at least spending a lot of time listening to the tone masters and soaking it in. Your creativity, phrasing, technique and inventiveness are so important, but your tone is your DNA and your musical stamp. You can have all the flash in the world, but if your tone sucks, you’re nowhere. I’d rather have a great tone and less chops than all chops and no tone.

I’d rather have a great tone and less chops than all chops and no tone

Sue Foley

It means so much that people have been saying that they like the tone on this album. But it isn’t just about me. There’s Chris with his mic placements, and Mike who was stubborn about all of us being in one room. So you’re hearing the guitar through all of these other instruments, too.

When we enjoy hearing master singers like Aretha Franklin or Ray Charles, the reason their voices sound so compelling isn’t just because of their phrasing or vocal technique. It’s also their timbre and sound that we love.

Yeah. It’s the same thing with guitar. Your tone is your voice.

Buy a copy of Pinky’s Blues by Sue Foley here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"When they left town, I went to the airport and got to meet Ritchie, and he thanked me for covering for him." Christopher Cross recalls filling in for a sick Ritchie Blackmore on Deep Purple's first-ever show in the U.S.

"It’s as if all of Jeff Beck’s genius is right here on one album. There’s a taste of everything.” Joe Perry riffs on Beck, the Yardbirds and "The 10 Records That Changed My Life"