“You Certainly Don’t Want to Be Looking for Commercial Success”: Andy Summers Reveals the Evolving Strategies That Keep His Creative Life Busier Than Ever

“You have to be very much engaged in the pursuit of finding new and unique ways to express your art,” says the Police guitarist

***The following appeared in the Holiday 2019 issue of Guitar Player***

It’s a very good thing being Andy Summers, but perhaps not for the more obvious reason pop fans might surmise.

Sure, no one can say it wasn’t colossally awesome to be one-third of a legendary band that was once the biggest act in the world, won a whole bunch of Grammy Awards, sold millions of records, performed in arenas and stadiums across myriad countries and was inducted into the Rock and Rock Hall of Fame in 2003.

Believe it or not, Summers’ story has two elements that may be even more astounding than his being a member of the Police.

First – and this is a life lesson for all who dive headlong into the beautiful morass that is the arts – his creative curiosity never slowed. He kept exercising his muse and expanding his chops, and he continued to produce work.

In the musical arena, Summers has released 15 solo albums in addition to a goodly number of collaborative LPs and guest appearances. He has also composed or contributed to numerous film soundtracks.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But wait – there’s more!

He wrote his autobiography, One Train Later, in 2006 and has penned essays for other publications. His latest book, Fretted and Moaning, was released in 2021.

Then there’s the photography career: His magnificent black-and-white photographs have been collected in four volumes to date and celebrated in museum and art gallery exhibitions all over the planet.

In 2015, he executive produced the documentary Can’t Stand Losing You: Surviving the Police, which was directed by Andy Grieve and based on One Train Later.

The second element is that Summers is hardly in any kind of “Hey I’ve done tons of stuff and now it’s time to get off the Tilt-A-Whirl and rest” decline. In fact, he is almost as busy today as some ambitious youngster burning to rule the world.

A rocker who was semi-retired, either by choice or popular standing, certainly wouldn’t be jotting down in his or her Google calendar all the things Summers has done recently.

Here’s a brief list: He worked with the Fender Custom Shop and Leica to produce two limited editions: the Fender Custom Shop Monochrome Strat and the Leica M Monochrom Signature Camera.

He brought his solo multimedia show, A Certain Strangeness, where he improvises guitar to images culled from his photography book, to galleries in the Netherlands, France and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

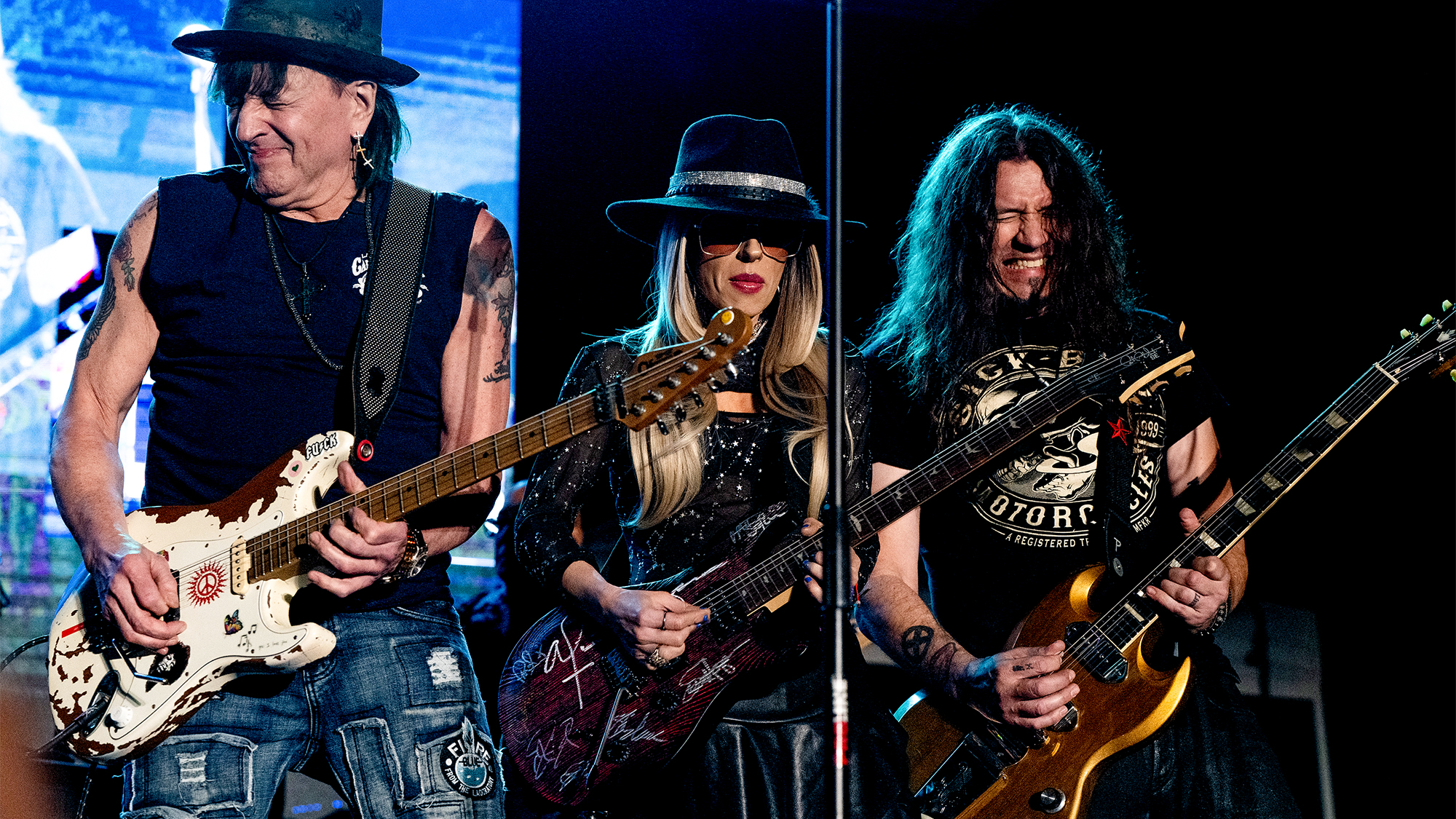

And, in a wacky career boomerang of sorts, he toured with the Brazilian Police tribute band Call the Police (with bassist Rodrigo Santos and drummer João Barone), looking all fired up and happy in the group’s YouTube videos.

None of this takes into account the many days Summers goes to his studio to work on music, test new guitar gear, pore over photos, deal with any legacy Police business and strategize his next creative moves.

At the risk of appearing too high-brow, Summers’ tireless productivity shows yet again that true artists don’t slow down. Like Picasso, Balanchine and Hitchcock, you create because it’s what you do, and you do it until mortality comes calling.

While it would take volumes to dive comprehensively into every aspect of Summers’ artistic life, we can visit some touchstones of his musical approach with the Police and beyond.

We should all be lucky enough just to keep up.

The Police were birthed during that boiling cauldron of the punk-rock movement in London. What was that like for you, Sting and Stewart Copeland?

It was like this: You had to be punk or you couldn’t even think about getting a gig. You’d never get one, because the punk scene pretty much ruled everything in London. There was a sort of religious fervor about it, and it was a bad moment if you were offering something other than raw anguish, let’s say.

Record companies were signing any old shit as fast as they could if they thought it was punk, and corporate-rock bands were changing their vibe and appearance almost overnight

Andy Summers

It was like a great recession of music. It was horrifying. Record companies were signing any old shit as fast as they could if they thought it was punk, and corporate-rock bands were changing their vibe and appearance almost overnight. Everything was out, except punk, and that was freaking everyone out. It was like some great lemming suicide rush to be in style.

Before I joined the band, Stewart was desperately trying to write something that was fast and furious. I’m sure Sting made some contributions in that regard, as well, but the timing wasn’t right for Sting to truly emerge as a songwriter in the punk era.

Before, after and during the early years of my being in the group, everyone involved was locked into just sustaining the band’s life, basically, by having the appearance of a punk band. It was all very dodgy, and it didn’t really work. We weren’t real punks, as it were. We were kind of fake. We could play fast and furious, but, yeah, we were suspect. We were sort of too good to be included in the scene.

Was Sting’s creativity hampered as a writer by the punk movement?

Oh, I didn’t mean to say that Sting didn’t emerge as a songwriter until after the punk thing. He was writing all the time, and he had a lot of songs already. He had “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic” right from the start. But when I joined, the possibility that these types of songs could be played was revealed to him. The whole atmosphere changed.

Punk music having different sounds is crucial, and one of the things about the punks was that they were okay with reggae

Andy Summers

The early resistance to the band is interesting to me, because in the States, punk was branching out into these pockets of punk poetry, art, journalism, acoustic punk, and so on. I loved that the early Police fused punk energy with reggae, and I remember being pissed off if a magazine or newspaper called you “blond posers” or dismissed the music.

It was an interesting time, that’s for sure. But what you said about punk music having different sounds is crucial, and one of the things about the punks was that they were okay with reggae.

However, I don’t believe we made it a political move. It wasn’t at all like, “Oh, let’s do reggae, then they’ll like us.” There was no deep analytical thought. We were just trying to pay the rent, and the reggae thing came slightly out of necessity and slightly out of our trying to do something different musically. It was pretty organic.

Soon, this thing started to pull itself together, and the true Police emerged. But not without lots of intensive rehearsal, I might add. We practiced all the time.

The Police’s punk-reggae hybrid may have been organic, but it had to bubble up from somewhere. What inspired or triggered the fusion?

Reggae and Bob Marley were definitely a heavy presence at the time. The music was very popular. You couldn’t get away from it. But, for us, the reggae influence was kind of a musical convenience, particularly for Sting. He could play those more spacey bass lines and sing over the top. He didn’t have to hammer out 16th-note or eighth-note bass lines in every song.

We could do something with reggae that would probably be acceptable in the punk scene

Andy Summers

Instead, we could do something with reggae that would probably be acceptable in the punk scene. When these things came together, they eventually mutated into “Roxanne” and “Walking on the Moon.”

We also started to emerge organically from the whole politics of punk, as well as from trying desperately to get a gig, quite honestly.

I love that Sting didn’t want to play da-da-da-da-da all the time and sing. It’s amazing how attacking a creative or technical challenge can lead to something new and exciting.

Exactly. Sting is really brilliant at being able to play independent bass lines from his vocal melody. I mean, anyone could have said, “Well, we can play reggae bass lines too.” But you know what? It’s not very easy. In fact, it’s really difficult unless you’re talented, and Sting is talented.

For some other bassists who sang, I’m sure it was probably much easier to just hit eighth notes and get to singing.

What was typically the first thing you did when Sting would show you and Stewart a new song?

I’d always address the vocal, because I’d never want to play even a single note that would conflict with his singing. I had to take care to make sure whatever I did was being supportive to the melody, but once I changed the chord voicings to where I thought they should go from what Sting originally played, it all got a lot more interesting.

I’d always address the vocal, because I’d never want to play even a single note that would conflict with his singing

Andy Summers

Some session players I’ve interviewed have said songwriters would often play open, folk-style chords to them, and they’d have to develop seductive parts from there. Did Sting provide similarly basic templates for you to work from?

No, it was never like that. He wouldn’t just strum a G chord. He’d always have the harmony down, but he would say, “Figure out what you want to do on the guitar.” And I would always try to do something different with his chord progressions – all the classic things I do, like arpeggiations, taking out the thirds of the chords, playing parallel fifths, or adding ninths, and the way I would use the Echoplex, so on and so forth.

It’s also whether you’d start on a downbeat or an offbeat, and how you’d react to whatever pattern the drummer is playing. For me, it was also about when to use muscle and when to use space.

On that note, can you talk about how you approached the trio format?

My thing about playing in trios is that it has to be different parts all of the time. When people play what I play, it just seems dumb. I’ve had this trouble with other musicians where I would start playing something and they’d begin playing what I’m playing. No! Play against me, not with me. Then it starts to sound like music.

How so?

Call it counterpoint, I suppose. But this is really a deep thought about making music. How it happens for anyone is based on years of experience, how you feel time, and everything else. When you’re starting out, it’s sort of an unconscious process. Hopefully, you develop a feeling for it later and you can get more analytical about what you choose to play.

When I joined the Police, I discovered the MXR Phase 90. 'Oooh... It’s the sound of a jet flying over.' It was a big deal to me

Andy Summers

For me, in that context, we were three young guys becoming famous. This was really our moment, and it was sort of incumbent upon me to make the guitar interesting. I had to make the most of it. Being in a trio is about as naked as it can get, and I didn’t want to be a boring guitar player.

You played in the Animals in 1968 and came away with a deep knowledge of music and a lot of skill, but your sound was conventional. Then, in the Police, you became a wizard of effects and beautifully eccentric chord voicings. Was there a moment where this approach kicked in, or did it develop through experimentation?

That’s a good question. By the time of the Police, guitar technology was really starting to come about. During my earliest incarnations as a guitarist, there were just the tone controls on the amp and maybe I’d add a little reverb or vibrato.

Eventually, I’d try out a pedal with some novelty sound. When I joined the Police, I discovered the MXR Phase 90. “Oooh... It’s the sound of a jet flying over.” It was a big deal to me.

Because of the option for added sonic textures, or was there more to it?

Guitar effects suited me because it was all down to me to spread the guitar around over a one-to-two-hour show and make it sound interesting all the time. It wasn’t my sensibility at that point to just use a blasting, overdriven guitar tone in a trio. I wanted to do something else.

Perhaps, I’m a bit more fragile. I like delicate sounds and spacey sounds. But it kind of all came together in the Police, partly due to my personality and partly practical. You know, “Let’s keep changing the sound of the band a lot so that our concerts are more dimensional and exciting.”

Put simply, the effects have to serve the music

It was an interesting challenge, and it was all very simple in the beginning. For example, I think I just had an MXR Dyna Comp, an Electro-Harmonix Electric Mistress and an Echoplex when we recorded “Walking on the Moon.” But I became noted for using effects early on, and it gave the band a very distinctive sound.

Of course, it evolved from something simple – a few pedals – to a custom Pete Cornish pedalboard, which was state-of-the-art in England.

Some guitarists just stomp on a pedal and they’re done. But there was more light and shadow in what you did. It seemed that you would really marry a particular effect to just the right guitar part, and use a cool inversion to bring everything together in a way that was almost cinematic in its scope.

Put simply, the effects have to serve the music. Even today, when I compose, the starting point is a sonic thing – a quality. I sit in my studio with all these various devices, and at first it’s playful. I hook them up this way and that way to see what they can do. Suddenly, something may emerge from all of this electrical chemistry, and you identify it as fresh: “Well, I haven’t heard that!”

A sound can be the inspiration point. Often, I’ll record 32 or 64 bars of something – maybe playing freely, or maybe playing to a click track – and see what that promotes.

But how does what you choose to compose often sound so otherworldly, whether it’s a hit song in the Police or an instrumental from a solo record like Triboluminescence?

I think if you spend your life doing music – like with all things – you get more sophisticated, and you probably go more and more toward abstraction. This is certainly true for photography, and it’s true for music, as well.

I think if you spend your life doing music – like with all things – you get more sophisticated, and you probably go more and more toward abstraction

Andy Summers

Maybe you spend years doing all the things that are expected of you as you develop your art, and you can still follow all the rules and such when you want to, but you also start looking for new territories.

There’s all this information on the outside that you’ve spent a lifetime accumulating, and you also have to rely on the world inside your head. You don’t want to repeat yourself. Some of this process you can define, and some of it is indefinable.

I do know that you have to be very much engaged in the pursuit of finding new and unique ways to express your art. You certainly don’t want to be looking for commercial success.

I’m not playing around with these things trying to make a hit. I’m trying to stay interested.

Order Andy Summers' latest album, Harmonics of the Night, here.