Yngwie Malmsteen Dishes on How He Went Back to His Roots on 'Blue Lightning'

"If you ask me what I like to play, it’s hard rock with that symphonic-classical feel. That’s what I prefer. Fifty Marshall stacks and a smoke machine!"

Arguably the most immediately recognizable name of all is that of Yngwie, the man who invented an entire genre of music known as neoclassical rock.

Yngwie J. Malmsteen’s astounding technical ability and unprecedented approach to virtuoso guitar playing set the bar to a previously unimaginable level when he was first heard on record in 1983, on the self-titled debut album from American heavy-metal band Steeler.

For those old enough to remember, Malmsteen’s initial appearance in the U.S. press was in Mike Varney’s “Spotlight” column in the February 1983 issue of Guitar Player. The tape he submitted to Varney has surfaced on YouTube and serves as a sobering example of the difference between a great guitarist and one who is truly gifted. The 19-year-old’s style was already fully formed and unlike anything else that came before it. Critics will sometimes try to point to some of Malmsteen’s influences, such as Ritchie Blackmore, but his playing and chops were from another universe.

At the time of his emergence, the undisputed god of all things shred was Eddie Van Halen. Remarkably, Malmsteen rapidly became as influential as Eddie, and was copied by many — from players who threw a few harmonic minor runs into their solos to imitators who appropriated his technique wholesale. The copycats are considerably fewer these days, but Malmsteen’s 1984 debut album, Rising Force, remains one of the definitive go-to shred albums of all time.

Malmsteen is currently promoting his new release, Blue Lightning (Rising Force). Early rumors tantalizingly suggested it would be a blues album. In actuality, it features his signature takes on a number of classic rock staples, mixed in with a handful of original songs. Performed entirely by Malmsteen and recorded in his own studio, Blue Lightning is a testament to his ability to take songs like the Rolling Stones’ “Paint It Black” and Eric Clapton’s “Forever Man” and make them his own. In addition to playing all the instruments, Yngwie sings all vocals, as he has since 2016’s World on Fire. His voice has continued to develop with each release, making the final product an even more personal statement.

Malmsteen has a reputation for taking no B.S. and pulling no punches with interviewers, but his sense of humor is often underestimated. Not only can he laugh at himself and the absurdities of the music business but he is also grateful to sustain a lucrative career in this age of the ever-shrinking music business. Given Guitar Player’s pivotal role in his rise to prominence, he was especially happy to reconnect with the magazine to discuss his new album and early years in America.

Blue Lightning features some interesting song choices that are well outside what people would expect of you, like “Forever Man” and “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” How did you go about selecting which songs you’d cover?

Everyone knows me for the neoclassical style, and for years people have said, “You should do a blues album, man!” Then, about a year and a half ago, Mascot Records actually did ask me to do a blues album. I said, “I don’t think I want to do a blues album — but I could do a ‘bluesy’ album.” They wanted to pick some classic songs for me, but I said I’d rather come up with the tracklist myself. They liked what I chose, so that worked out well. Some selections were made automatically — for example, songs that I’d loved forever — and some were songs that I’d found interesting when I heard them on the radio but never tried to play or sing. “Smoke on the Water,” of course, was something I’ve played my whole life, since I was a kid. In terms of singing, it was very interesting to approach some of the songs I’d never played before and to think about the phrasing and the keys. But because I am always on tour, I’d have to go home to cut a song, then head back out again to gig. The album was really created song by song.

As I understand it, your home studio is not just a small project studio but a full, professional facility.

For sure, and I’m always adding things and improving and upgrading it. A couple of months ago, before I went on the road, I had the space completely refurbished. I had a new console put in, and everything was updated to the top specifications. But then I went out on the road, so I haven’t really had a chance to use the new equipment yet. I’m looking forward to getting some time with the new gear.

You recorded your first covers album, Inspiration, in 1996. That disc included Deep Purple’s “Demon’s Eye,” a song that you’ve cut again on Blue Lightning. Why did you remake it?

I was eight years old and a little tyke when I got my first record. It was Fireball, by Deep Purple. Most versions came with “Strange Kind of Woman” on it, but mine came with “Demon’s Eye.” When I was growing up in Sweden, we had nothing like that music. So that album was a revelation, and I really loved that song. As it happens, when I recorded it for Inspiration, I did it in a different key and, of course, I didn’t sing it. But the song is amazing, so I decided to do it in the right key and sing it myself.

If you ask me what I like to play, it’s hard rock with that symphonic-classical feel. That’s what I prefer. Fifty Marshall stacks and a smoke machine!

It adds a new dimension to your music to hear you perform the vocals. It’s obvious that your vocal abilities have continued to develop over the years. Is that something you’ve focused on?

When I’m on the road, I don’t drink or smoke. I do my exercises, I get enough sleep, I drink some tea, and I sing every night. As a result, I’m developing all the time, and I’m not doing anything that might have a negative impact on my voice. The fact that I’m doing it so much helps it develop naturally and become stronger. It seems like the more I sing, the stronger it gets. I have very good ancestry for singing. Both of my uncles were opera singers, my mother sang in a choir, and my father and sister are also singers. When I grew up in Sweden, I was always the singer in my band as well.

Why didn’t you sing on your earlier albums?

In the past, I wrote all the lyrics and the melodies, and then I had the singers sing exactly what I wanted them to sing — no more and no less. But of course, to sing it yourself is much better. I think partly what happened is that when I came to America, I had an invitation to join a band — Steeler — and then I went on to join Alcatrazz, where I was the guitarist. When I did the first album of my own in 1984, the logical development was to focus on playing. I didn’t really question it or give it a second thought. Now I am singing everything in the live show, except for a couple of songs that the keyboard player sings.

Let’s go back to your earliest appearance in the U.S., in Guitar Player’s “Spotlight” column, in the February 1983 issue. You’ve said you’d been a reader of the magazine for years. What was the music press like in Sweden when you were growing up?

We had the NME and Melody Maker from England, and Guitar Player from the U.S. They were magazines that I bought religiously. I always thought that I would move to England, as it was only a couple of hours away by plane. All my favorite bands were English, and it seemed like the obvious thing to do, as there was nothing in Sweden. But when I saw the column in Guitar Player, I thought, I’m gonna send my tape in to that!

Listening to the tape now — you can find it all over YouTube — it’s amazing how fully formed your style and technique were even back then. Obviously, you’ve continued to refine and improve over the years, but in essence, anyone hearing that first tape couldn’t fail to be blown away. Did playing guitar come easily to you?

It’s an interesting question. For my fourth birthday, I got a violin, for my fifth I got a guitar, and for my sixth I got a trumpet. At first, I didn’t really play anything. But when I was seven, I saw Hendrix on TV smashing his guitar, and it made me think about playing. Immediately, I picked up my guitar. It just felt very natural. It was the same when my son, Antonio, began to play guitar. He sounded like he’d been doing it for years. He is an amazing player.

The story of how you moved to America in 1981 has been told over the years — how you arrived with your guitar, a toothbrush and a pair of jeans. Is it accurate, and did you feel confident you’d have success?

It is true. But to come to America as I did, you have to remember that ’70s Sweden was like a musical desert. A wasteland. When Guitar Player invited me to come to America, it was a very easy decision to make, and it completely replaced my original, loosely formed idea about moving to the U.K.

Did Shrapnel [Mike Varney’s record label] put you on a retainer?

I didn’t get any money, man! I was living in Steeler’s warehouse, where the rest of the band lived. It was pretty disgusting. I was only there for about a month, and then the word got around. People were asking, “What the f*ck’s this kid doing?” No one knew what my style was. I love Van Halen, but my style was completely different, and everybody was following that kind of direction, copying Eddie’s style. The note selections for my riffs and solos were completely different from what everyone else was doing. Unlike Europe, I think the American rock audience had very little, if any, exposure to classical music. They had no knowledge of where I got these ideas, or that I’d been influenced by Bach, Vivaldi and Paganini. They didn’t know what I was doing!

I remember the first gig I did. We were opening up for Glenn Hughes, who is a dear friend of mine, and the first time we played, there were about 70 people. A couple of days, later we were playing the Troubadour in Santa Monica, and you could see down the street from the dressing room upstairs that there was a line going around the block. I asked some guy at the club, “Who’s performing tonight who can draw such a crowd?” and he said, “It’s you!” That’s how fast it was. It went crazy, like a mania. I couldn’t believe after all my years of struggling in Sweden, I was in America one week and it was already happening like that.

How did you feel when other guitarists began to copy your style?

Irritated. [laughs] Yeah! It was so funny, because it was so blatant. Then you’d see the interviews with them: “Who were your influences?” “Bach.” Yeah, sure! But whatever, y’know?

Imitators aside, do you feel satisfied that your vision has been validated?

Yes. It is really remarkable. On this tour I’m playing 39 cities in America, and wherever I go, it’s packed. I wonder how this is still happening to a kid from Sweden 35 years later. I’m still here, I’m still doing it and people are coming to see me. I’m blown away. It is very rewarding for me, because I never compromised. I always said, “It’s my way or the highway!” I’m a very lucky man. But it doesn’t feel like any time at all has passed. It’s all gone by so quickly.

You’re frequently referred to as a neoclassical shredder, but it would be just as easy to say you’re a rock guitarist. You’ve recorded an acoustic album, and you’ve recorded in other styles as well. Are you bothered when people pigeonhole you in that way?

Sure. It’s the dumbest thing someone can say. One of my favorite bands in the world is AC/DC. I love that band, and I love Angus. They play three chords. Their music hasn’t changed, their style hasn’t changed. Why should it? If somebody comes out with something that’s theirs, that’s what’s amazing and great. Music is not a fashion show, where you have to have something different every year. Musicians are like artists, with their own style of painting. You can hear my earliest recordings from before I came to America, and you can hear that I’ve always composed the same way. Because that’s me.

But, yes, I’ve done an acoustic album, a symphonic album. And this new album is different. I don’t do all the same things. If you ask me what I like to play, it’s hard rock with that symphonic-classical feel. That’s what I prefer. Fifty Marshall stacks and a smoke machine!

You’ve always had a lot of amps onstage kicking out some serious volume. Have you ever suffered any issues with your hearing?

What? [laughs] No, my hearing is fine. It is loud onstage, but it is the quality of the sound that matters — the sweetness of the Marshalls. I think P.A. systems can be problematic, but onstage the volume doesn’t trouble me. I think if you went to a lot of shows and stood out front, where you get the full impact of the P.A., that could affect your hearing.

You love the late-’60s Fender Stratocasters with the big headstock and the various customizations you prefer — scalloped fretboards, for example. Do you have any interest in vintage guitars, given how different they are from your signature models?

I have old Strats from the first year of manufacture, as well as vintage Gibsons. I have a ton of vintage guitars, and I do love old guitars. But as far as playing onstage, I use my signature Strats. Fender is about to bring my new signature model out soon. It’s based on a ’68 Strat, whereas the ones I have usually played have been based on a ’72 Strat. That’s what my first main Strat was, the one that I nicknamed the Duck.

How much maintenance is required to keep your playing where you need it to be? Do you play every day, and do you have any kind of regimen?

When I’m at home, there’s always a guitar sitting next to the sofa, and if I’m watching TV, I’ll play. I’ll often get ideas, then go to my studio and record them. My other passion is my Ferraris. I do spend a lot of time with them. I don’t think I would ever usually go more than a day without playing the guitar. Now that I’m on tour, I’m playing all the time, of course.

You seem to arouse a lot of hostility in other guitarists and musicians, who are often very vocal with their criticisms of you. For example, last October, Jake E. Lee went on a tirade on the Talk Toomey podcast about your personality and how he doesn’t like your playing. How do you feel about these attacks, and what do you think is behind them?

[laughs] I don’t know! I don’t even pay attention to stuff like that. First of all, music is not a competition, and secondly, I’m very much in my own little world when it comes to music. I definitely don’t want to be influenced by other people. I like music to come from within. I don’t pay attention to what other people do. I think it’s a distraction. If they say bad things, then I’m sorry to hear that.

You’ve given a lot of interviews over the years, and you’ve probably answered the same questions many times. Is there any question you wish you’d been asked instead of the usual ones?

[laughs] No. I understand that there’s going to be certain things everyone will ask, and if I’m promoting a new album it’s understandable that there will be a lot of similar questions. But I’m really grateful to still be talking to magazines about my music after all these years, and to have a career that’s lasted this long. I feel very lucky.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Guitar Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful guitar publication for passionate guitarists and active musicians of all ages. Guitar Player magazine is published 13 times a year in print and digital formats. The magazine was established in 1967 and is the world's oldest guitar magazine. When "Guitar Player Staff" is credited as the author, it's usually because more than one author on the team has created the story.

“It’s tongue in cheek!" The story of The Beatles song with three guitarists, three bassists, McCartney on drums — and a lyric that made enemies

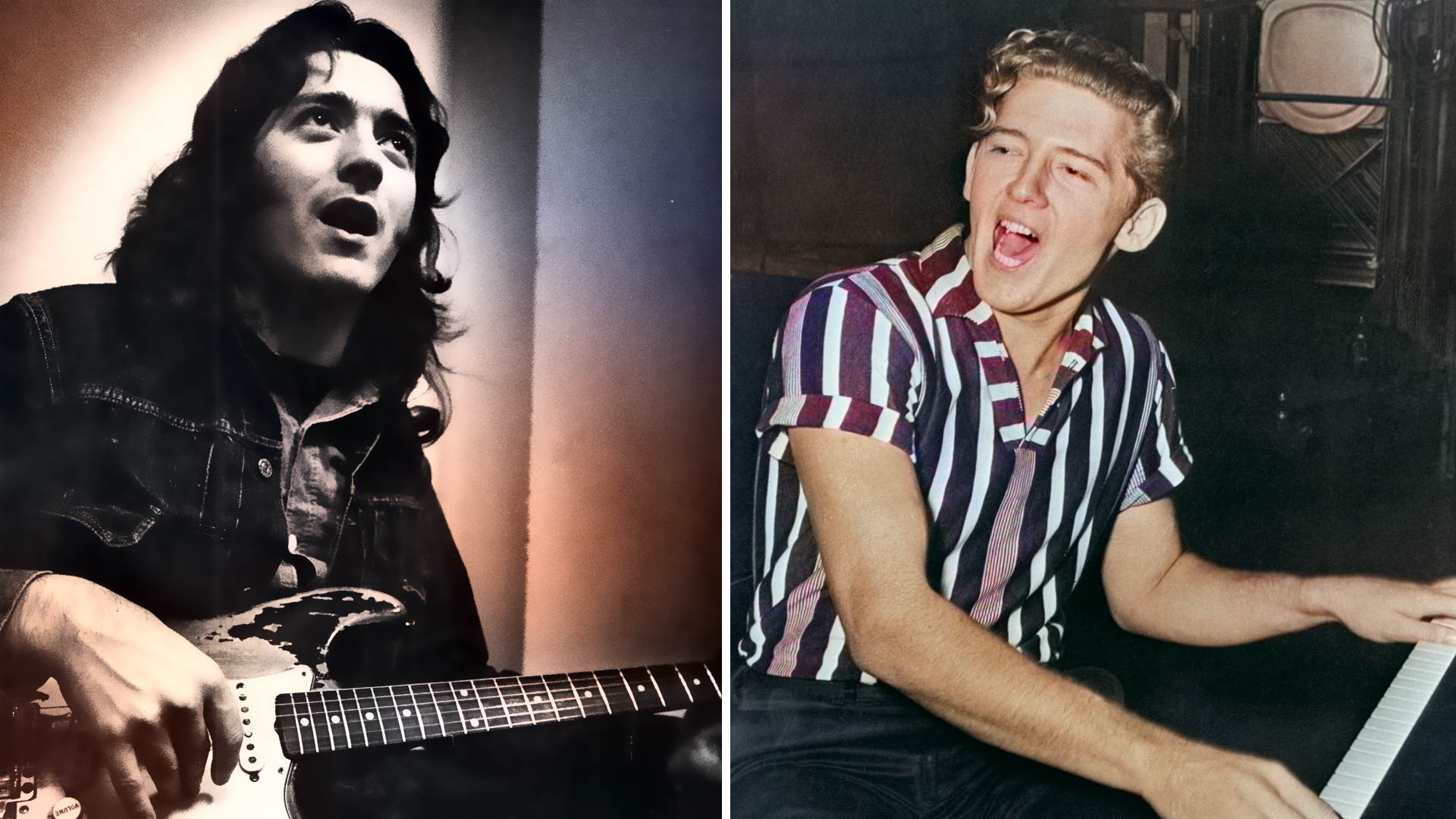

“He goes, ‘Play, boy,’ in that very southern way. I start taking my solo, sweating: ‘He’s going to hit me! I know it’s coming.’” How Jerry Lee Lewis terrorized Rory Gallagher, Dave Davies and Ritchie Blackmore