John Frusciante Called This Album “Beautiful” While John Petrucci Played It “Over and Over and Over”: Here’s Why Yes’s ‘Close to the Edge’ Remains a Prog Rock Masterpiece

“It’s astounding. Even I can see that,” said Steve Howe

“Yes may be the single most important of all the progressive rock bands,” claimed Geddy Lee while referencing the band's fifth studio effort, Close to the Edge, as among his “favorite rock albums of all time.”

For many fans of prog rock in the early 1970s, the arrival of the Yes album Close to the Edge in 1972 was not unlike the release of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band some five years earlier.

Like that early psychedelic landmark, Close to the Edge was a sprawling, genre-melding sonic wash of sound unlike anything anyone had heard before.

From its 18-minute title track, which took up all of side one, through the operatic sweep of the 10-minute-long “And You and I” and the hard rock-jazz fusion of its closing track, the evocatively titled “Siberian Khatru,” Close to the Edge wasn’t just another album; it was a sonic journey that you experienced from one end to the other (preferably on headphones), and then, in all likelihood, repeated once the needle reached the inner groove of side two.

It’s little surprise many fans thought Yes hadn’t just gone close to the edge – they’d gone clean over it.

Beyond the sheer grand scope of the album and level of musicianship displayed, what impressed me most about Close to the Edge was the ensemble playing on display. Just listening to it, you could tell Yes were a tight and supportive band.

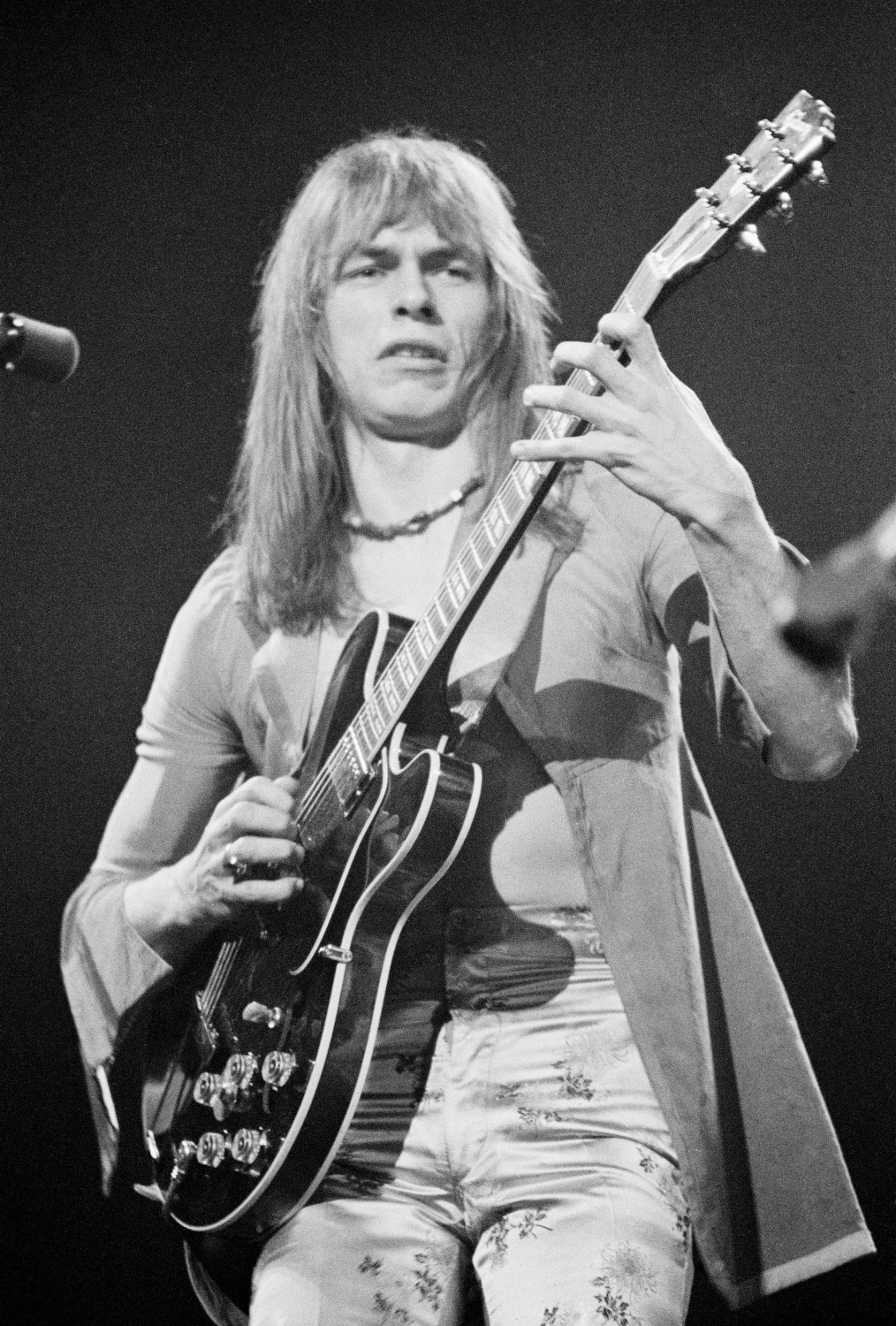

The music gave equal room to Steve Howe’s breathtaking range of guitar virtuosity – from Duane Eddy-era rock and roll to John McLaughlin fusion – and Rick Wakeman’s dazzling keyboard skills, all of which was ably supported by the melodic “lead” bass work of Chris Squire and the mind-blowing jazz-tinged drum work of Bill Bruford.

The fact that they all performed this music on behalf of Jon Anderson’s cryptic lyrics made the group seem like a sect of some mysterious religion.

The underlying sense I had was that this was how a band was supposed to be: like a supportive team. Which is very much the way Steve Howe describes Yes at this time in its development.

“We were young, enthusiastic, and adventurous, and we had this incredible breakthrough success with Fragile,” the guitarist told GP. “We saw our next album as a real opportunity to prove our worth as a band. The door had been opened and we weren’t going to go backward. We wanted to sharpen our skills as far as writing and arranging.”

Although the success of the “Roundabout” single helped launch their top-ten 1971 album, Fragile, Yes eschewed radio-friendly hits while pursuing a different direction that allowed the band to expand their music without any regard for commercialization. “We cared if people listened to it,” Howe told Guitarist, “but we didn’t want to fit into the box of being a three-and-a-half-minute hit band.

“We went in the opposite direction. Sometimes Yes purposely decommercialized music.”

Order Close to the Edge here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.

"This 'Bohemian Rhapsody' will be hard to beat in the years to come! I'm awestruck.” Brian May makes a surprise appearance at Coachella to perform Queen's hit with Benson Boone

“We’re Liverpool boys, and they say Liverpool is the capital of Ireland.” Paul McCartney explains how the Beatles introduced harmonized guitar leads to rock and roll with one remarkable song