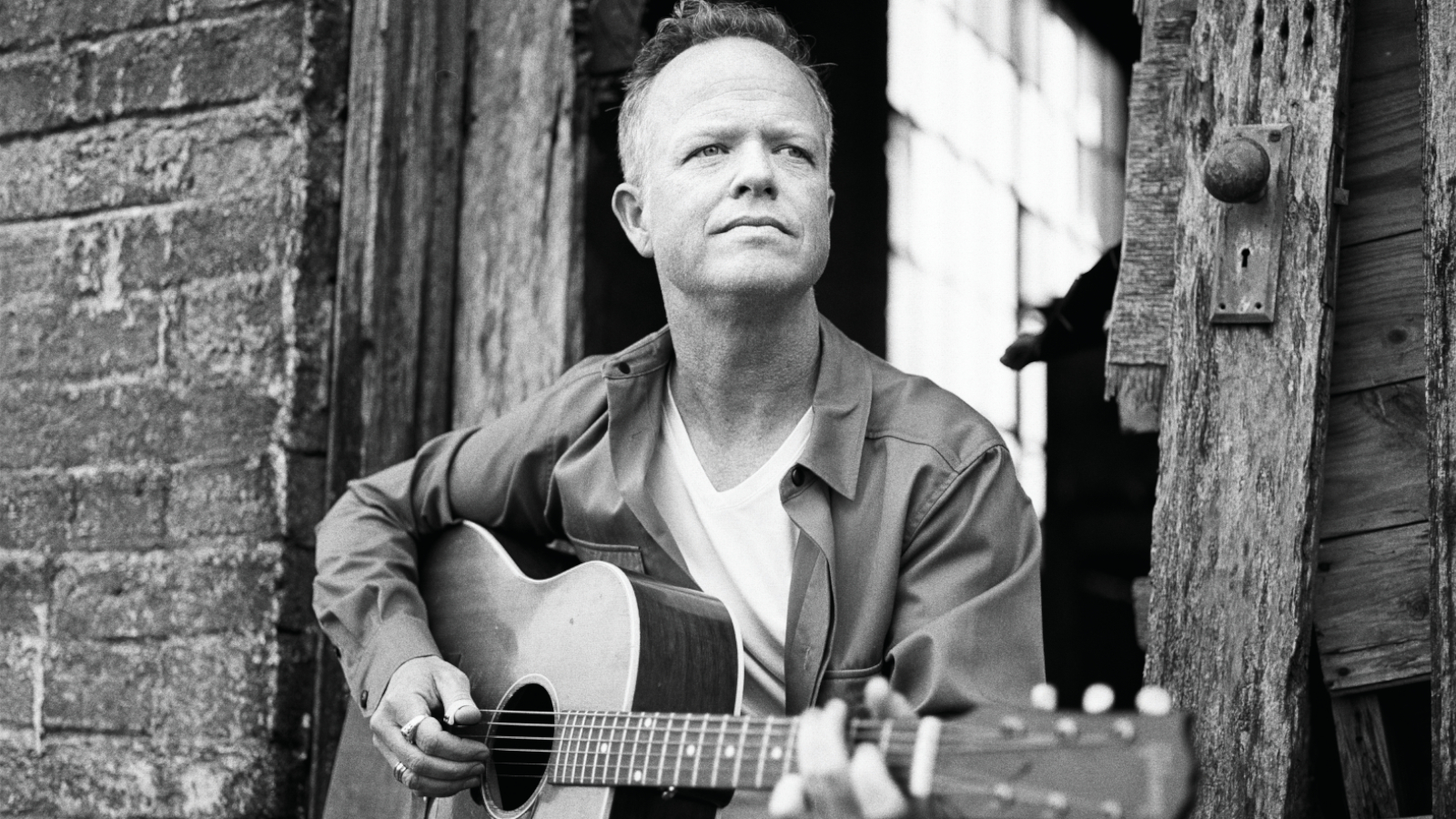

With 3 Solo Albums in 2 Years, Steve Dawson Hasn’t Let a Worldwide Health Disaster Slow Him Down

The Canadian artist, engineer, producer and podcaster has found the early '20s to be some of his most productive years.

Canadian-born Steve Dawson was well into the second act of his music career when the pandemic hit.

After a successful run as an artist, sideman and producer north of the border, the guitarist had relocated to Nashville. He set up a busy studio there while continuing to record and tour with, among others, future Americana superstar Allison Russell’s band Birds of Chicago.

Remarkably, Dawson has found the past two years to be some of his most productive.

For starters, he recorded three solo records, the first of which, Gone, Long Gone (Black Hen Records), offers a master class in all things slide, from the Cooder-tastic “Dimes,” to the Weissenborn-style Hawaiian inflected “Kulaniapia Waltz.”

He also continued his terrific podcast, Music Makers and Soul Shakers, which features in-depth player-to-player interviews with musicians, including guitarists Ariel Posen, Guthrie Trapp, Charlie Hunter, Jim Campilongo, et al.

And he set up a remote recording crew capable of safely churning out records for musicians young and old.

People started asking me to produce. That appealed to me because it allowed me to stay off the road

Steve Dawson

Yet somehow he still found time to get deep into the weeds with GP on the making of his record and the joys of multiple amps.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Did you develop your career in Canada as a solo artist, session player or both?

It was a bit of everything. I made solo records and had a duo with a violin player doing unusual acoustic instrumental music. Weirdly, the latter took off; we won awards and got booked at festivals.

And then people started asking me to produce. That appealed to me because it allowed me to stay off the road.

How did you develop as a producer? Do you have engineering skills?

I’d been around studios and made records. I was not confident enough to engineer, but I could gather a group of people, put them in interesting scenarios, and make everyone comfortable.

I knew how I wanted things to sound, so I hooked up with a couple of engineers and learned a ton from them. Now I engineer all the time. Also, 12 or 13 years ago I started mixing records for people.

With players not congregating in studios, how did you create tracks for the new record?

One thing I got out of Covid was making friends with a click track again

Steve Dawson

One thing I got out of Covid was making friends with a click track again. I hadn’t used one for about 15 years and had hated them. I would do a rough outline of the song to a click, and send that to the drummer – either Gary Craig in Toronto or Jay Bellerose in L.A.

I would get the song back and maybe arrange it slightly differently, or do a little drum editing, and then send it to the bass player, Jeremy Holmes in Vancouver.

At that point, I would record all my keeper tracks, do a rough mix of everything and send that to other musicians.

Every day was like Christmas because I’d get these great files in return. Those might inspire me to change some of my parts or guitar sounds. It was time consuming, and not the way I would’ve usually made a record, but fun.

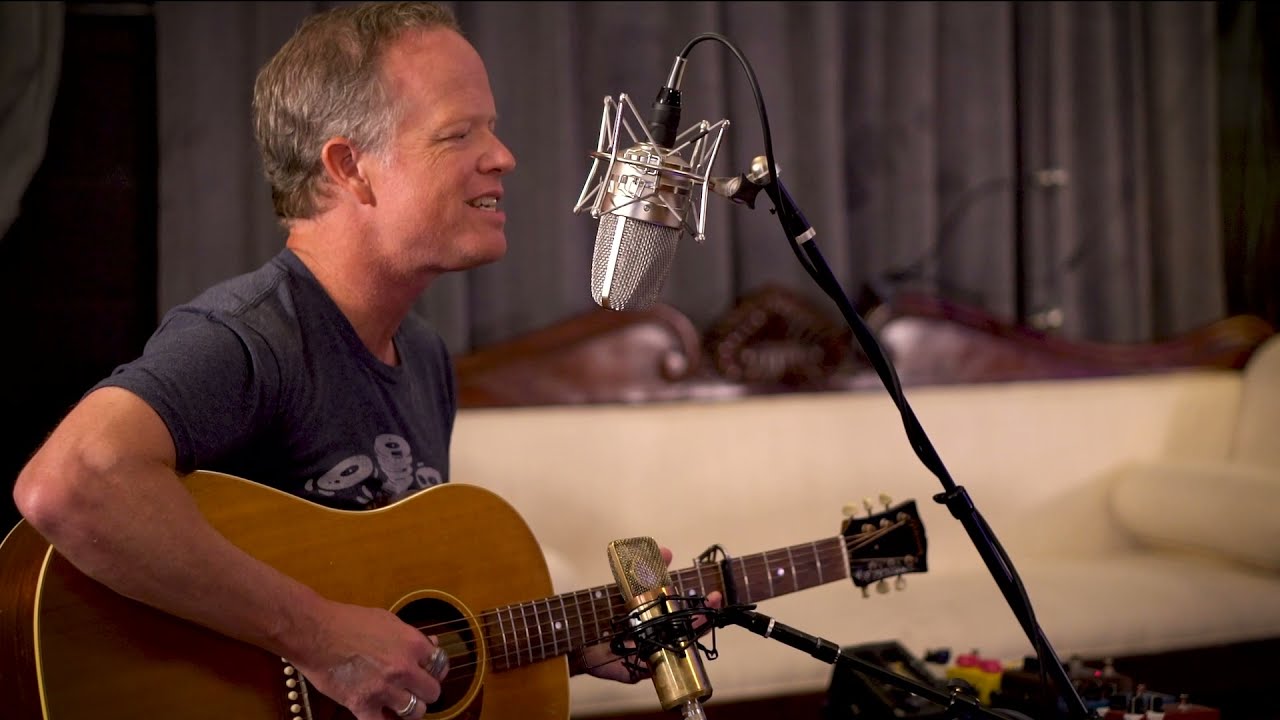

In the video for “Dimes,” it looks like you’re playing a Ry Cooder-type guitar.

It’s a Fender Stratocaster I bought new in ’91. I was into Stevie Ray Vaughan then, but by ’94 I was sick of Strat sounds so I got rid of all the pickups.

Over the years, I’ve probably had 30 different combinations in there. I have always used it for slide, but during Covid I said, “Screw it, I’m going full-on Coodercaster.”

I got a gold-foil pickup and lap-steel pickup from Mojo Pickups in England.

What strings are on it?

I mostly use D’Addario NYXLs: .015 on top to .062 on the bottom. I usually tune the two E strings to D [low to high, D A D G B D]. Coming from playing in open D and open G, I find it is the best of both worlds.

By ’94 I was sick of Strat sounds so I got rid of all the pickups

Steve Dawson

I’ve got my slide on my fourth finger and the middle four strings are tuned standard, so I’m able to still play all kinds of chords.

Which slide are you using?

I picked it up in England. Some guy tagged me on Instagram and said he made it. It looks like glass, but I don’t know what the hell it is. [laughs] It’s a little heavier than glass.

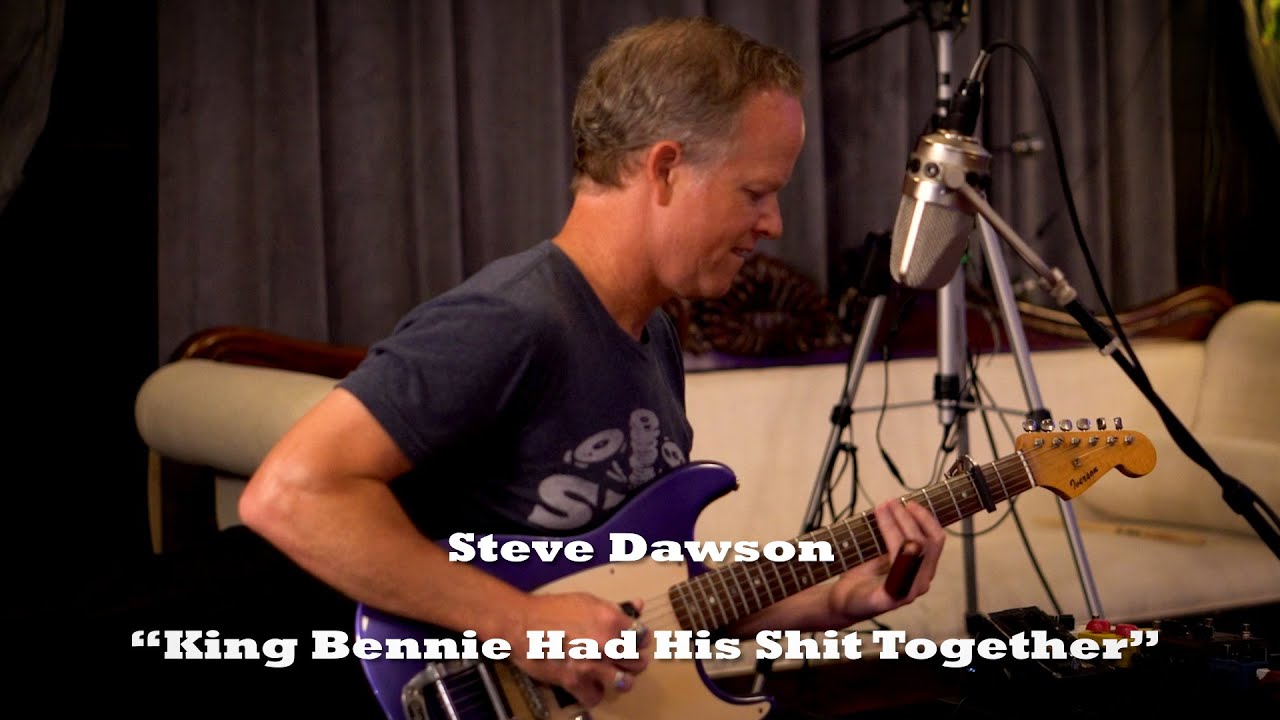

What about amps?

I had four amps set up the whole time. I had a Radial Shotgun box that splits the guitar signal four ways. It deals with any phase-inverting or ground issues.

One amp was a Flot-a-tone accordion tube amp from the ’50s. It gets hot and smells funny [laughs], but it sounds great.

There was a ’53 tweed 5E3 Deluxe. It’s the super-primitive one that you can’t jump the inputs on. You can’t turn it up very loud either; it has to be close-miked.

The third was a Premier 88, which is a crazy amp that comes attached to a separate cabinet that has one 15-inch and two three-inch speakers. It has five white tabs; when you flick them down, they cut certain frequencies. There’s a tremolo on it that’s somewhere between a brown Princeton or Deluxe and a choppier Twin.

Finally, there was a Fender Princeton. I’d use a combination with no EQ. I’d just turn one or another of the amps up in the mix to create the tonal palette.

The tremolo comes from the amps, for the most part, although I did have a Strymon Flint

Steve Dawson

Did you ever use fuzz for the slide solos?

I used fuzz a lot. My Vancouver friend Chris Young’s company, Union Tube and Transistor, makes amazing pedals. His early prototype fuzz, the Buzz Bomb, gets a lot of play in the background.

His other one, the Sone Bender, is a Tone Bender knock-off, but it’s more reliable than a vintage fuzz pedal. I used that on a lot of the solos.

For more subtle overdrive I used a Greer Lightspeed.

The tremolo comes from the amps, for the most part, although I did have a Strymon Flint. A Strymon Volante created some delays, and I used a Tel-Ray oil can delay for slapback.

Your Weissenborn-style lap guitar sounds different on different tunes.

The tunings are different, usually variations on C tuning. For bluesy or original stuff, like “Bad Omen,” it’s [low to high] C G C G C D. Sometimes I vary it, like tuning the high string to a C unison or Eb, or the 2nd string C to a Bb for a dominant 9 chord.

But when I play traditional ’20s and ’30s Hawaiian music, like “Kulaniapia Waltz,” I tune it to G [low to high, D G D G B D]. G tuning makes me play very differently.

Also, on that tune, the mic would’ve been a lot farther away, whereas with “Bad Omen” it’s closer and more compressed, so it sounds more aggressive. On that tune you’re hearing a combination of the acoustic sound and an amp signal from the pickup adding some grit.

There’s a bit of tremolo, but it’s subtle because it’s on the electric channel only.

After a year we realized everyone we were recording was over 40, so we started a contest to connect with younger people

Steve Dawson

You also play some smoking single-line solos.

When I play “normal” guitar stuff, I tune to standard and usually use a Nash T-style. That’s my main electric guitar, but I also have a Gibson ES-335 and an Epiphone Casino.

Tell us about the Henhouse Express Junior project.

It’s our name for an inexpensive way for people to record during Covid. We would Zoom with the artists to get their feedback on what the songs were about and what they wanted to hear.

We did the same process for my record. After a year we realized everyone we were recording was over 40, so we started a contest to connect with younger people.

It was free; there was no commitment and no strings attached. We just wanted to have fun and do something with kids. It does help promote our services to a new generation, though, which is great.

Gone, Long Gone is the first of three records you made for yourself during Covid. What are the others, and how do they differ?

The second is an all-instrumental pedal-steel psychedelic record called Phantom Threshold and will come out around July. It’s billed as Steve Dawson and the Telescope Three.

The third is more like the first, except it has more traditional stuff. Half is brand-new songs, but it’s geared toward interpreting old stuff.

Order Gone, Long Gone here.