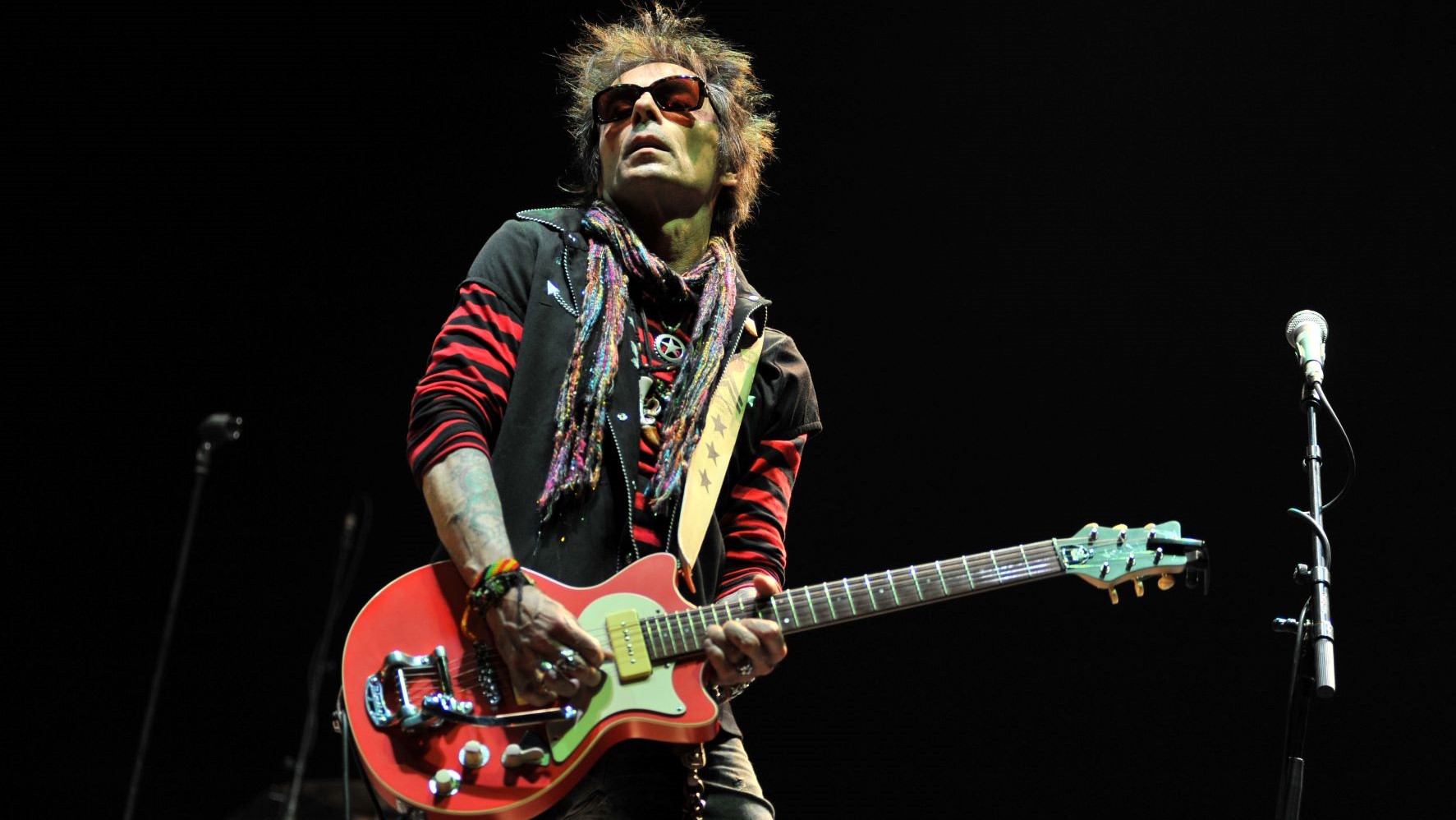

“When You Were Around David, the Process of Recording Wasn’t Weird Compared to the Rest of the Stuff Going On”: Earl Slick Talks David Bowie and John Lennon

Earl Slick can remember the last gig he played – right off the top of his head. “It was March 7th, 2020, with [former Sex Pistols bassist] Glen Matlock, in London,” he says. “Ever since then, I’ve been mostly on my own, like everybody. And let me tell you, you tend to go a little batty with so much free time on your hands.”

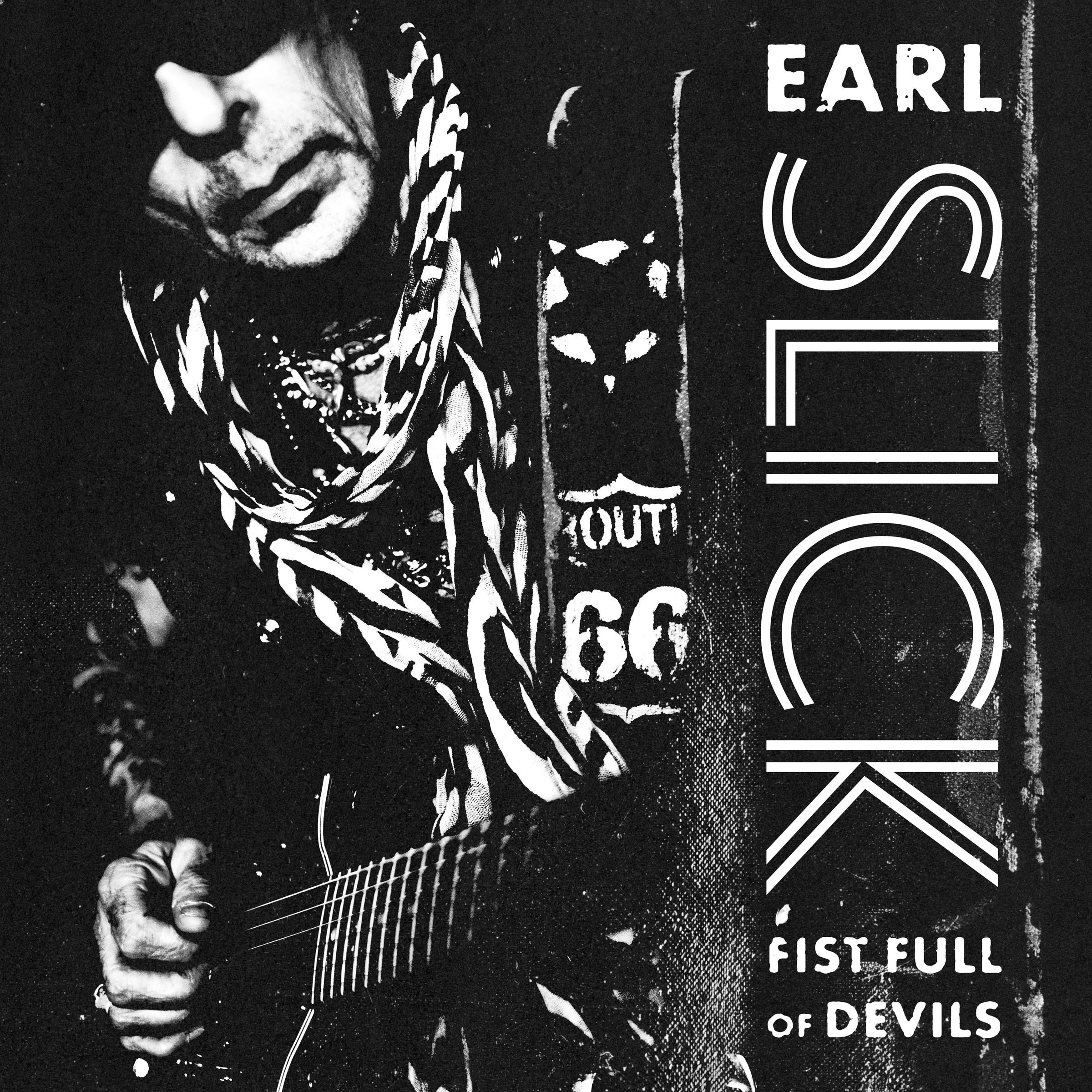

The veteran guitarist hasn’t exactly done nothing during the past year, and he says the period of relative isolation has been a blessing. It’s given him time to work on a memoir, which he says he’s close to finishing (“You keep thinking you’re close to being done, and then you go, Oh, wait, there’s that other thing!”), and it afforded him a clear chunk of time to record Fist Full of Devils, his first solo album in nearly 20 years.

Mostly, though, the extended lockdown has provided Slick with the opportunity to do something he rarely does. “I just sat around and thought a lot,” he says. “I’m always so busy doing this or that, and if I’m not doing something, my mind is on whatever I’ve got to do next. For the past year and a half, things kind of stopped, and I’ve had a lot of time to just think about who I am and what I’ve done.”

He pauses. “Funny things come into your head, like, ‘Did I just fake my way through it all?’” He laughs. “But then I go, ‘No, come on. That’s crazy.’ Some of the stuff I did, you just can’t fake it.”

Fakers don’t get to play with rock royalty like David Bowie and John Lennon, two of the more celebrated names on Slick’s star-studded resume.

Slick was just 22 years old in 1974 when he began what would become a 30-year, on-and-off association with Bowie. After hearing the “unschooled, street player” jam along to unmixed and unreleased recordings of songs such as “Rebel Rebel,” Bowie hired Slick to replace Mick Ronson in his band for the Diamond Dogs tour.

“I don’t know how many people were up for the gig, but I got it,” Slick says. “After that, I was off and running.”

Years earlier, like millions of other teens, the guitarist sat mesmerized in front of his TV set as the Beatles were introduced to America on The Ed Sullivan Show. The next day, he pestered his father to buy him an electric guitar – a $30 secondhand Danelectro.

“Did I ever think that one day I’d get good enough to play with John Lennon?” he asks rhetorically. “Of course not. The idea still blows my mind. Lennon was this huge guy; he was a hero. A little kid from Brooklyn doesn’t get to be in a room with him.”

Slick took all of three guitar lessons before embarking on what he calls “a dedicated period of musical self-education.” Instead of playing rudimentary exercises, he hunkered down with the radio and records.

At first, he picked along to the pop songs of the British Invasion bands, but soon he gravitated to the Rolling Stones and the Animals, and from them he learned about their roots – Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy and Chuck Berry.

“I got really into the blues and became sort of the outlier at school,” he says. “My friends were still learning to play pop songs, and I’m playing the blues.”

Moving to New York City in the early 1970s, Slick tried to make a go of it in bands. There was an outfit called Mack Truck, and for a short time he played in a duo called Slick Diamond (with Scottish singer-songwriter Jim Diamond).

Acing the Bowie audition changed everything for Slick, and together they changed music.

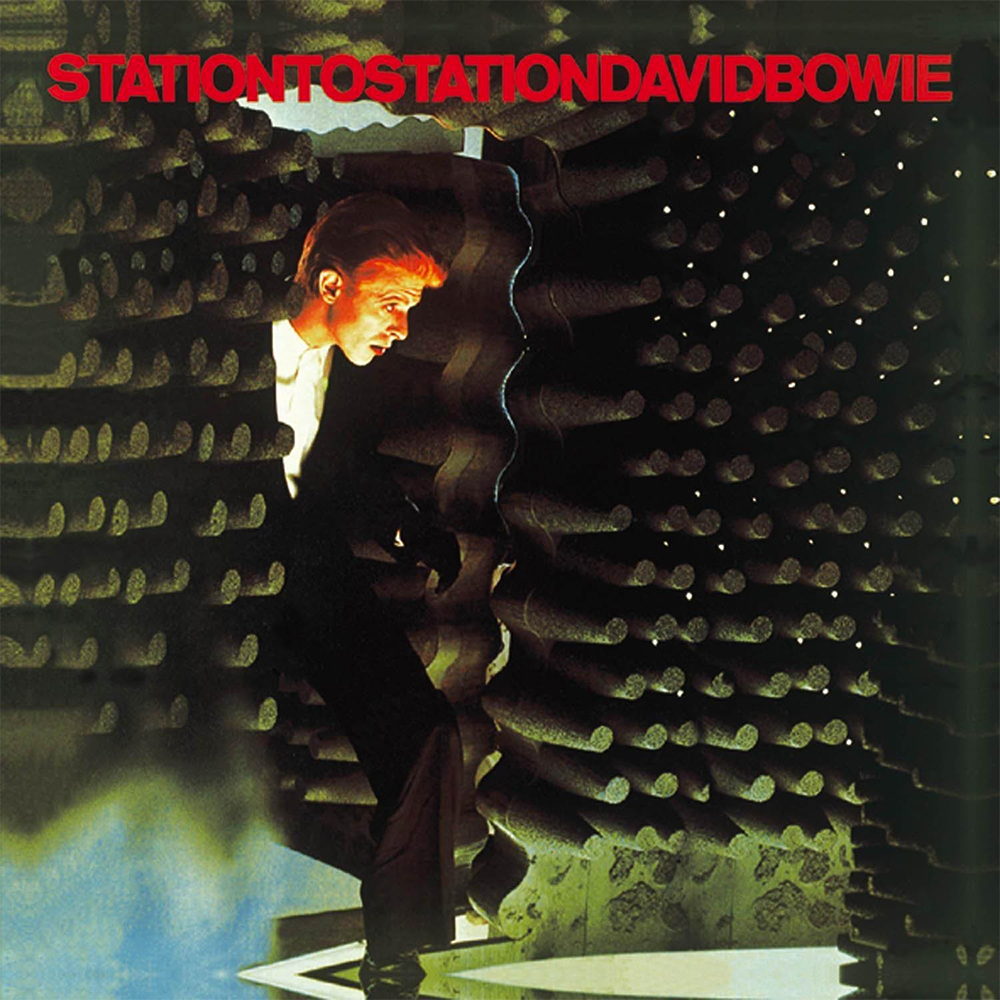

Their daring experimentation on the title track to 1976’s Station to Station, fueled by Slick’s ragged, at times atonal leads, combined funk, soul and art rock for an overall effect that became revolutionary.

Between tours and sessions with Bowie, Slick collaborated with artists such as Ian Hunter, John Waite, Tim Curry and David Coverdale, among others. After playing on John Lennon’s Double Fantasy (as well as tracks for a follow-up record, which was released in 1984 as Milk and Honey), he worked with Yoko Ono on her 1981 album, Season of Glass.

Along the way, he formed the band Phantom, Rocker & Slick with the Stray Cats rhythm section of Slim Jim Phantom and Lee Rocker, as well as the short-lived band Dirty White Boy.

“I did a lot,” he says with a laugh. “That’s one of those things that has run through my mind during this whole pandemic. I don’t spend a lot of time on social media, but I recently hired a guy to work my web page and all that, and before I knew it, fans started popping up, and it reminds you of all the things you’ve done. It’s sort of mind boggling.”

Slick’s fans will find a lot to like about Fist Full of Devils, a diverse set of instrumentals that spans smart-alecky blues, poignant torch songs, white-knuckled rockers and a host of tracks that toss genres into a blender.

At age 68, the guitarist still has plenty of spunk in the trunk. He doesn’t so much strum an acoustic as dance with it, and his electric solos sing, swoon, sputter and roar.

My whole thing is feel. Personality. It’s what’s carried me this far, so I’m sticking with it.

Earl Slick

“The funny thing is, playing solos is my least favorite thing to do,” he says. “I could play rhythm all day and be perfectly happy. When I was cutting these songs, I didn’t construct every note of the solos – I never do that. But I hear things in the chord changes and that guides me through a melody.”

He makes it clear that anybody expecting a record of guitar-clinic shred can look elsewhere. “The world doesn’t need another wanking guitar album,” he says. “Besides, I’m not proficient enough to pull that off. My whole thing is feel. Personality. It’s what’s carried me this far, so I’m sticking with it.”

What was it like in New York City for a young guitarist in the early ’70s? Was it a hotbed of players all competing for the same gigs?

At the beginning it was competitive, but not between players – it was competitive in terms of bands. This went on for a while, and then things started to change. As we started to play out more, that’s when people were being offered gigs as guitarists. At that point, it started to become competitive.

Did you have the mind-set of, “Well, if my band doesn’t make it, I could be a session guy”?

No, not at all. The only thought I ever had about anything – other than having my own band – was that, if the Rolling Stones ever needed a guitar player, I was their guy. I don’t even think the word sideman was coined yet. My idea was to stick with my band, get a record contract and have a hit record. I didn’t consider any other kind of career.

Which guitars and amps were you using at the time?

I had one guitar and one amp: my ’65 SG Junior and a 100-watt Marshall stack. And the cool thing was we had buddies who used to hang around, and the idea of being a roadie appealed to them. I was a smart little fucker, and I learned that I didn’t have to haul my own stuff around when I could get other people to do it.

I wasn’t nervous about the audition, but I didn’t tell anybody about it, in case I didn’t get it.

Earl Slick

You were only 22 and hadn’t been around much when you auditioned for Bowie. How did you not get rattled by his fame?

The funny thing was, I wasn’t too nervous. I mean, I knew David was a major star, but I only owned one David Bowie record – Aladdin Sane – and the reason why I bought that was because of Mick Ronson. I mean, “Jean Genie” is “Mannish Boy.” “Panic in Detroit” is Bo Diddley.

Mick’s guitar playing was a twist from the way it would normally be played, and I loved it. So I wasn’t nervous about the audition, but I didn’t tell anybody about it, in case I didn’t get it.

When Bowie hired you, did he ever verbalize what he liked about your playing?

In his own roundabout “David” sort of way. Once I got the gig, I got a little rattled because I didn’t know if I had to play and sound like Mick Ronson. Did I have to play the stuff note for note from the records? Quite frankly, I was terrified, so I asked David if that’s what he wanted. Thankfully, he said, “No. I hired you because I like the way you play. I want you to do what you do.” That was a big relief.

How did your experience with Bowie expand your playing beyond the blues rock that you grew up on?

It opened me up, but not so much at the beginning. At the very start, I was just doing what I always did. You can hear that on David Live. I was just playing how I played at the time. When we hit Station to Station, that’s when things changed.

You’re dovetailing into our next question.

Yeah, Station to Station – everything changed because he changed. In his own way, he would push me into new areas to get me uncomfortable. Even though he still wanted me to do what I did, there were certain things he wanted me to rethink. It opened me up, for sure. What was nice was that these ideas he had felt very natural to me.

So even the title track to Station to Station – which now sounds so trendsetting and prescient – it didn’t seem avant-garde to you?

I don’t think you can tell what’s trendsetting at the time you’re making something. Whatever we recorded, my attitude was, This is what we’re doing. I didn’t really think about the impact it would have.

The thing about that song – and the whole record, really – was that David didn’t bring in finished pieces. Take the title track: That was three pieces of music that he brought in. I thought they were going to be three separate songs. Somehow it glued itself together to become the epic that it is.

And that felt natural to you?

It just was what it was. The way we communicated was, “Here’s what we’re doing.” It didn’t seem weird. When you were around David, the process of recording wasn’t weird compared to the rest of the stuff going on.

Did he play you music he was listening to, bands like Kraftwerk, just so you could get an idea of where he was at?

No. No, he didn’t play me that stuff. He would try to feel me out in certain ways, though. Before Station to Station, he took me out to see Lou Reed and Roxy Music. He really liked what they were doing, and I think he was trying to feel me out and get my reactions.

What kinds of guitars were you playing on Station to Station?

I had an early ’70s Les Paul, a Strat from ’64 or ’65, and my SG. Oh, and my Gibson J-45.

John Lennon tapped you to play on Double Fantasy. The two of you had already worked together on David’s Young Americans album.

Yeah, it was at John’s request that I was on Double Fantasy, and it was based on us both doing “Fame” together. The funny thing is that I had no recollection of it – none – which was a running joke the whole time.

During our conversations, John would tell me the story of recording the track, and he knew that I was involved, but I couldn’t remember it at all. I was a little high back then, as we all were. But John remembered. I didn’t.

They were strange times.

Earl Slick

That’s so funny. Most guitarists would remember recording with John Lennon.

Yeah, well, they were strange times.

So you get a call to play on Lennon’s record, his return from retirement. That must have been pretty head-spinning.

It was way more head-spinning than Bowie because I was a real John Lennon fan. It was because of the Beatles that I was exposed to rock and roll and decided I wanted to get involved with it. And John was the guy that I gravitated toward. So yeah, it was a trip.

When John was in the studio with you, did he have firm ideas of what he wanted from you guitar-wise? Or did he just let you play to see where you were going?

He pretty much did the latter. What he would do with all of us as a group, he would go, “I want this kind of a feel.” He would guide you, but he didn’t dictate parts. I was the only one on the sessions that didn’t read charts, and apparently John remembered that from Young Americans.

He wanted one guy in the room who was more of a street player. The other people were the best session guys on the planet.

Did you ever play that crazy Sardonyx guitar that Lennon was using during those sessions?

Yeah. I even bought one. I wish I still had the freaking thing. I sold it to somebody, and I know who he is. Because it’s very important to the guy, I never offered to buy it back from him.

What did it sound like? Is there a track on Double Fantasy you can point to as an example?

I can’t mention a particular track. John used it a lot. It was a stick body with two wings on it, and it had a pair of humbuckers. I don’t really remember what it sounded like. I don’t even know why he bought it, because he still liked to play his Casinos.

A few years later, you stepped back into Bowie world after Stevie Ray Vaughan pulled out of David’s Serious Moonlight tour. How much time did you have to prepare before you hit the road?

I didn’t have any time at all. I mean, from the time they called me, I think I had maybe three or four rehearsals with the band. I had to learn the whole show.

Now granted, I’d either played or recorded half the show anyway, but there was new stuff I wasn’t familiar with, and I had to learn it. I sat with a cassette deck in my hotel room in Brussels and did the best I could to digest all the stuff.

Regarding the tunes he had recorded with Stevie, did David give you the same direction as he had when you first started working together – to just be yourself?

All he told me was, “We’ve got a big festival coming up really soon. Do you think you’ll be ready?” And little arrogant me said, “What, are you kidding me? I’ll be ready from the first gig.”

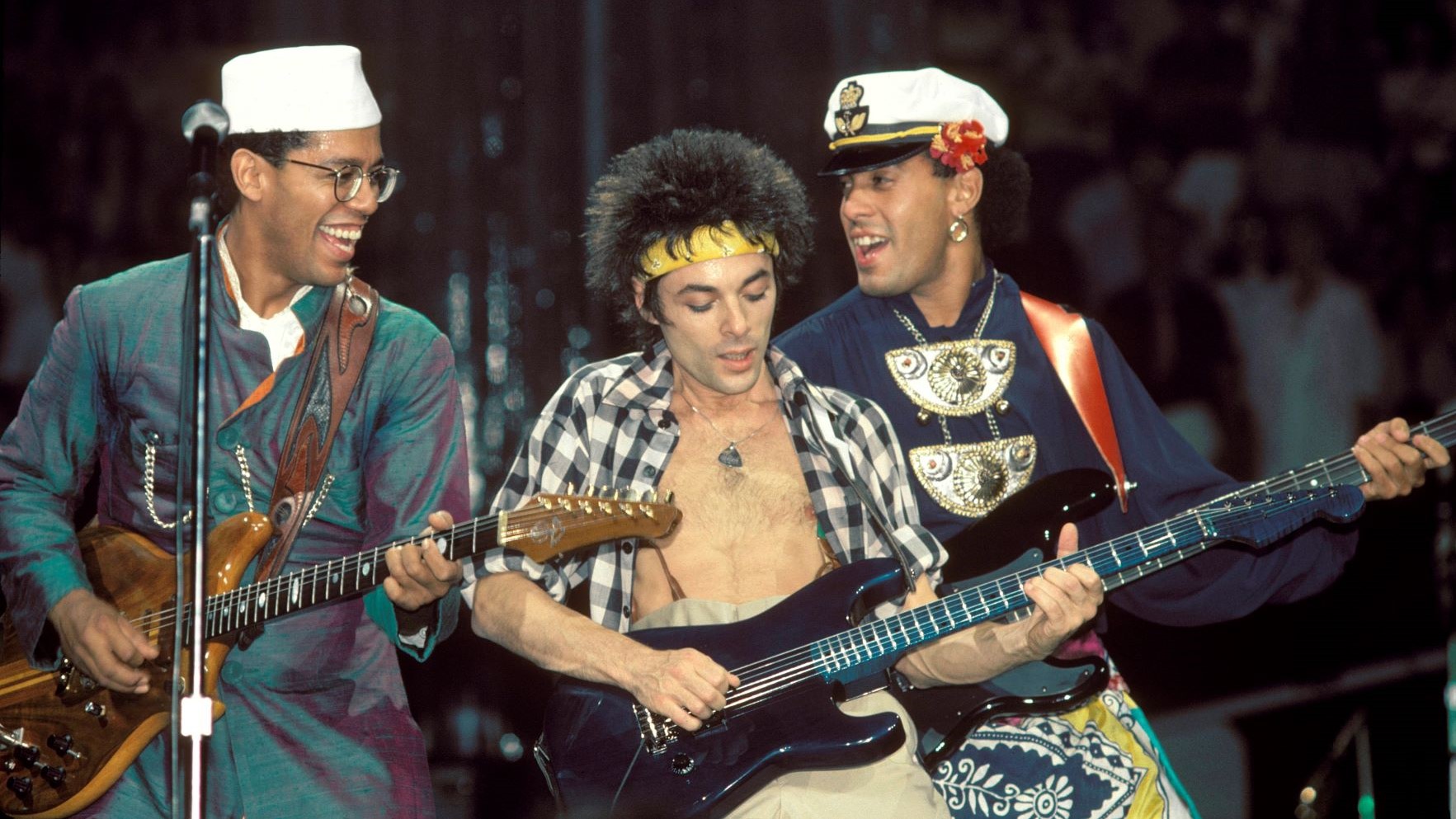

What was your relationship like with Carlos Alomar? You guys ended up as bandmates on that tour.

It was good. We had a good working relationship because our roles as guitar players were very defined. We didn’t play alike at all. He covered his bases, and I covered mine. There was no competition. Maybe if we played the same way it could have gotten strange, but that was never the case.

What’s the story with Mick Ronson showing up at a gig and trashing one of your guitars?

Oh, that’s a funny one. He sat in with us at an outdoor gig in Canada. I don’t know what song we were playing, but he borrowed one of my guitars – it was a custom-made DiMarzio – and he started swinging the thing around over his head and put some dents in it. I wasn’t even pissed off or anything, but I was a little terrified. [laughs] Now people pay a lot of money to get beat-up guitars.

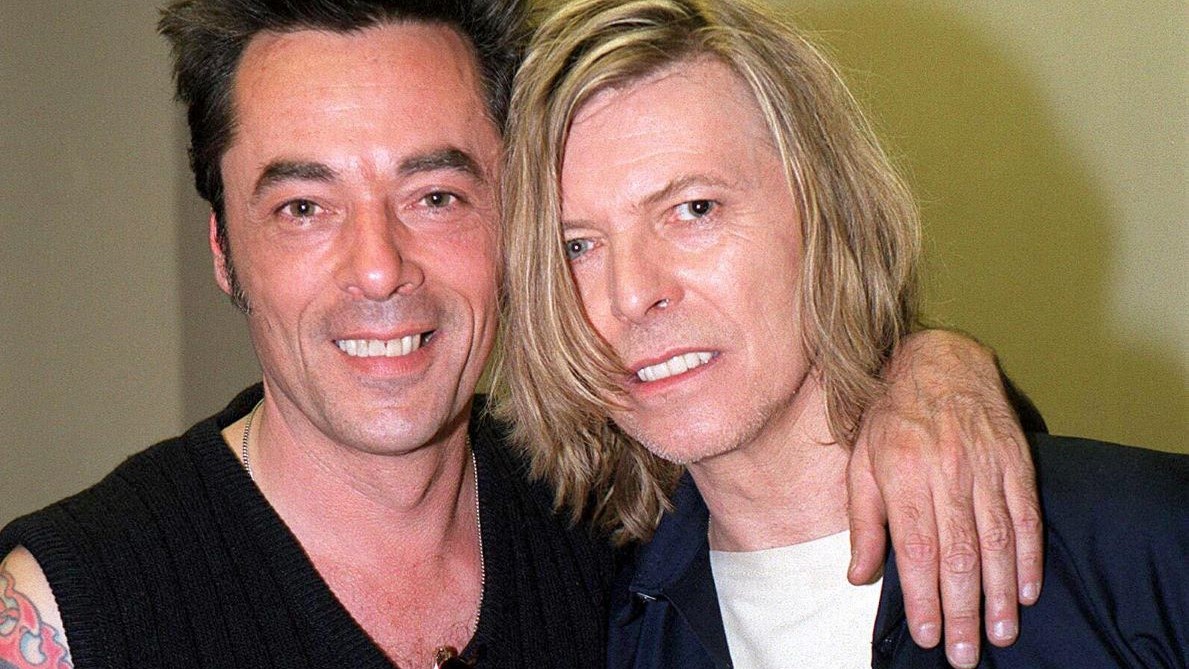

You worked with Bowie on a series of his latter-day albums. Would you speak during those long times apart? Did you have to renew your relationship?

Funny thing about that was, it was seamless. When we started working together again back in the late ’90s or early 2000s, we hadn’t seen each other or had any contact in a long time. I was on the West Coast at the time, so I flew to New York to play with the band he had, and the first thing David had me play was “Stay.”

David wasn’t even onstage with us – he was sitting on a lounge chair or something – but the second he heard me playing, this big-ass smile came across his face. It was like a minute hadn’t even gone by between us.

During the time we were apart, we both changed a lot, and our relationship grew tighter once we took up again. We talked a lot more about personal things, which we never did before.

Earl Slick

Now, what’s interesting is, it became more of an open relationship. We really became friends. Back in the day, we weren’t really friends, maybe because we were both so out of it. We weren’t enemies; we just weren’t buddies.

But during the time we were apart, we both changed a lot, and our relationship grew tighter once we took up again. We talked a lot more about personal things, which we never did before. So that was nice.

Your new album is notable among guitar instrumental records in that there’s a distinct lack of noodling. It’s virtuosity without showboating.

Yeah, well, I don’t do the noodle thing – that was never my thing. Some of the songs are really based in the piano as far as the writing. Al Morris, who played piano on the record, he would come up with really cool, unusual stuff, and that pushed me into all sorts of atmospheres – not so much melodies.

Some of the tracks, like “Vanishing Point” and “Black,” sound like they could be film scores.

Yeah, yeah. “Vanishing Point” is something I started writing in the ’90s. Al helped me get it in shape. “Black” is pretty cool. It sort of came from the frame of mind I was in at the time – a little tortured – but the inspiration for the overall sound comes from Angelo Badalamenti, David Lynch’s guy. I’m a major David Lynch fan, and I love what Angelo does with him. In the movie Fire Walk With Me, there’s this really ominous bar scene. It’s shot with red backgrounds, and there’s all kinds of weird shit going on. I purposely tried to write something with that same feel.

What’s cool is, although it sounds like a score, parts of it also feel like a jam.

That was the idea. There was just enough structure in it, and then out of the blue, Al started to play this sort of ’50s piano thing, in a happy, major key. We jumped on that. It goes from this dreary, dark, echo-y thing into this really happy bridge. It was a great trick.

I’ve gravitated right back to where I started – to the Teles.

Earl Slick

What are your main guitars these days?

I’ve gravitated right back to where I started – to the Teles. There’s a lot of Telecaster on the record. I used my famous signature model on it. Some of the little Hendrix-y rhythm things that you hear, these little double-stops that remind me of “Little Wing” – that’s not a Strat, although it sounds like one. That’s my signature model, with P-90s in it.

I also used my SG and an Eastwood Airline Tuxedo. The acoustics were mainly the two Gibsons and a Tacoma 12-string. That’s one of the best 12-strings I own.

I just do what I do, and people seem to like it. It’s always worked for me, so I can’t complain.

Earl Slick

Last question, and it sort of goes back to what we started talking about. Do you ever stop and ask yourself, “Why me? Of all the guitar players in the world, how did I manage to play with all these people?”

Oh, God, all the time. I mean, I look at a guy like Steve Lukather, who is just amazing. In my mind, he’s like a modern-day Tommy Tedesco or Steve Cropper. Steve Lukather is the only session guitar player I’ve ever heard who can convincingly play any style. If he’s doing a blues thing, he sounds like a blues player. If he’s doing jazz, he sounds like a jazz player. He doesn’t sound like a session guy faking it.

So this goes back to “Why me?” I mean, I’ve sat in with Steve, and I’m afraid to play around him. It’s like, holy shit. He’s embarrassing me. I can’t do what he does. Nobody can. I just do what I do, and people seem to like it. It’s always worked for me, so I can’t complain.

Grab your copy of Fist Full of Devils here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened