“What Drives Anyone Who Has Obsessive-Compulsive Leanings?” Juliana Hatfield Talks Creativity and Songwriting

The alt-rock songstress reveals the inspiration behind her many albums and collaborations.

Juliana Hatfield is best known for her alt-rock hits “My Sister” and “Spin the Bottle,” both from the Juliana Hatfield Three’s 1993 album, Become What You Are, and for her stint in the Lemonheads the previous year, when she played bass on It’s a Shame About Ray.

Those who jumped ship when the ’90s faded have missed a lot. In back-to-back releases like Beautiful Creature and Total System Failure, Hatfield expressed her love of pop songcraft and grimy blasts of distortion, respectively, a dichotomy she wields masterfully.

“I’m just trying to express who I truly am, and I’m a very conflicted person,” she says. “Even with my moods I’m like that. I go back and forth, and I’m always trying to figure out who I am and how to integrate my authentic self into one whole self. My music is just an expression of that.”

You’re known as a guitar player and songwriter, but you studied piano at Berklee College of Music before taking up bass. How did those experiences feed into the type of music you make?

I think that people with unique voices are born with those voices, so I don’t know how much Berklee helped me as a songwriter. It definitely helped me open up my ears – helped me to listen more carefully and more closely.

I never really paid much attention to how the different elements in a song were working together. I was not well-versed in the language and with theory. All the ear training and learning to distinguish intervals and chords really helped me communicate to other musicians.

Were you already playing guitar at that point?

I was getting really burned out on playing piano, but I used my piano-playing background to get into Berklee. I don’t think they would have admitted me otherwise, because I had no vocal training and no guitar training.

For one semester I studied jazz piano intensively. I learned how to comp and how to read a lead sheet, which ended up being really helpful to me later on. After that one semester, I could notate my songs, and now when I’m in the studio and I want to put a keyboard on a track, I can write myself a little lead sheet and play off of that.

Then I started studying voice at Berklee, because I had never had any voice lessons. At the same time I was starting my first band, the Blake Babies, and I was very new at playing guitar.

On 2019’s Weird, you layer elements like fuzzy riffs and solos onto a foundation of clean, articulate playing, which is also something you’ve done on earlier albums. Are you drawn to the opposite natures of those sounds?

They’re just little moments that are really exciting to me. Like on [1995’s] Only Everything, I really loved the solo on “Simplicity Is Beautiful.” I think it’s a couple of solos on top of each other. I was trying to capture that kind of feeling that a J. Mascis [of Dinosaur Jr] solo captures. It’s definitely not the same kind of dexterity with my fingers, but that was just a great moment for me.

I was trying to capture that kind of feeling that a J. Mascis solo captures.

Juliana Hatfield

There are a lot of really cool guitar moments on that album, like how the solo in “Dumb Fun” develops. I think in the beginning of the song I was trying to be like Kurt Cobain, playing the vocal melody on the guitar like in “Come as You Are.” Then I went off in different directions, and it just became this really fun thing.

You’ve done several side projects, like the I Don’t Cares with Paul Westerberg and Minor Alps with Matthew Caws of Nada Surf. What drives you to collaborate?

Emotional instability, I guess. What drives anyone who has obsessive-compulsive leanings? I can’t stop writing songs, and I have too many, so I have to find other people to record with so people don’t get barraged with too many Juliana Hatfield records.

Plus, Matthew Caws is one of my favorite singers and songwriters. To be able to work with him was kind of like a dream, you know? If I’m going to have an opportunity like that, I’ll definitely go for it.

What about Paul Westerberg? Were you a Replacements fan early on?

Yeah. Huge Replacements fan. A long time ago in the ’90s, Paul and I were supposed to do a tour together. He was doing a tour for one of his solo albums, but he threw out his back and had to cancel the tour, so that never happened, but we were in touch.

He had tons and tons of songs recorded. Some of them were just so great, and I would say, “Why don’t people know this song? Let’s work on this.”

It’s still just me alone in a room with an acoustic guitar. But I’m less miserable now. I’m not so focused on my own anguish in my songs.

Juliana Hatfield

You reissued your solo debut, Hey Babe, on vinyl. Does it feel different to pick up a guitar and write songs now than it did back then?

It does and it doesn’t. I mean, I still do it the same way. It’s still just me alone in a room with an acoustic guitar. But I’m less miserable now. I’m not so focused on my own anguish in my songs. I think my subject matter has shifted a little bit away from myself. I’m not as anguished as a songwriter. I’m more confident, maybe. I don’t know if that makes my work better or worse. Some people want their artists to be tortured and suicidal.

Check out Juliana Hatfield’s latest album – Blood – here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jim Beaugez has written about music for Rolling Stone, Smithsonian, Guitar World, Guitar Player and many other publications. He created My Life in Five Riffs, a multimedia documentary series for Guitar Player that traces contemporary artists back to their sources of inspiration, and previously spent a decade in the musical instruments industry.

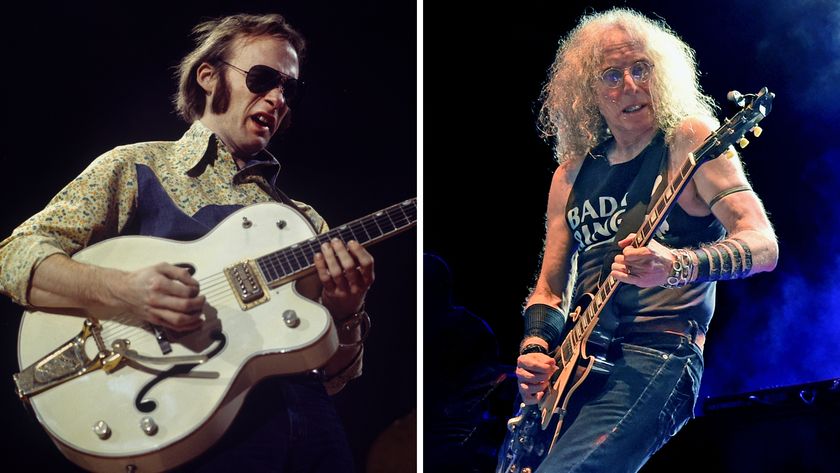

“I don’t see why I have to go through all the BS of high school to learn music." Watch 17-year-old Alex Lifeson argue with his parents about his future with Rush in a 1971 documentary

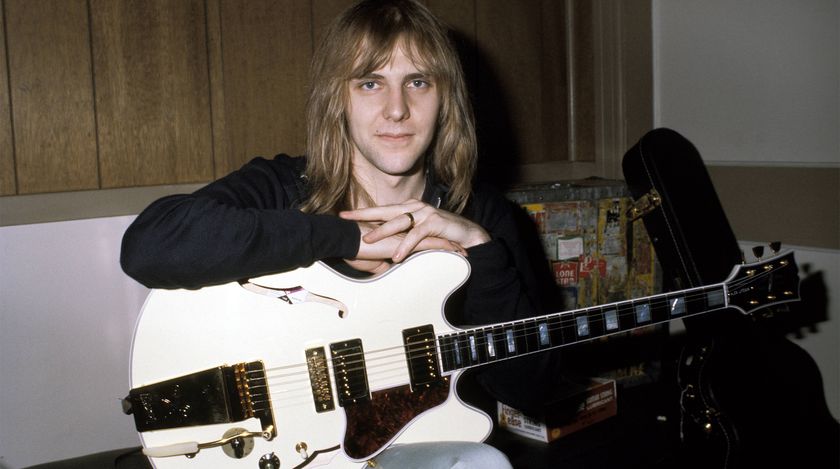

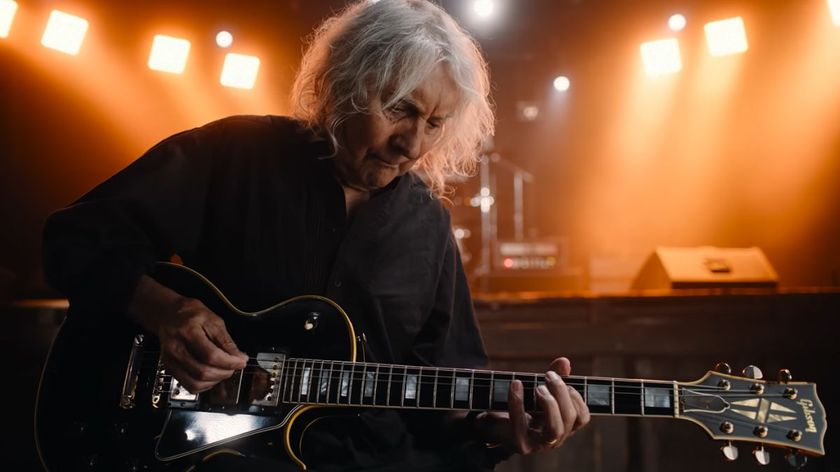

“Eric never asked for the guitar back. He was happy that I was enjoying it and using it onstage.” When Albert Lee received a Les Paul Custom from Eric Clapton, he had no idea how much history it held