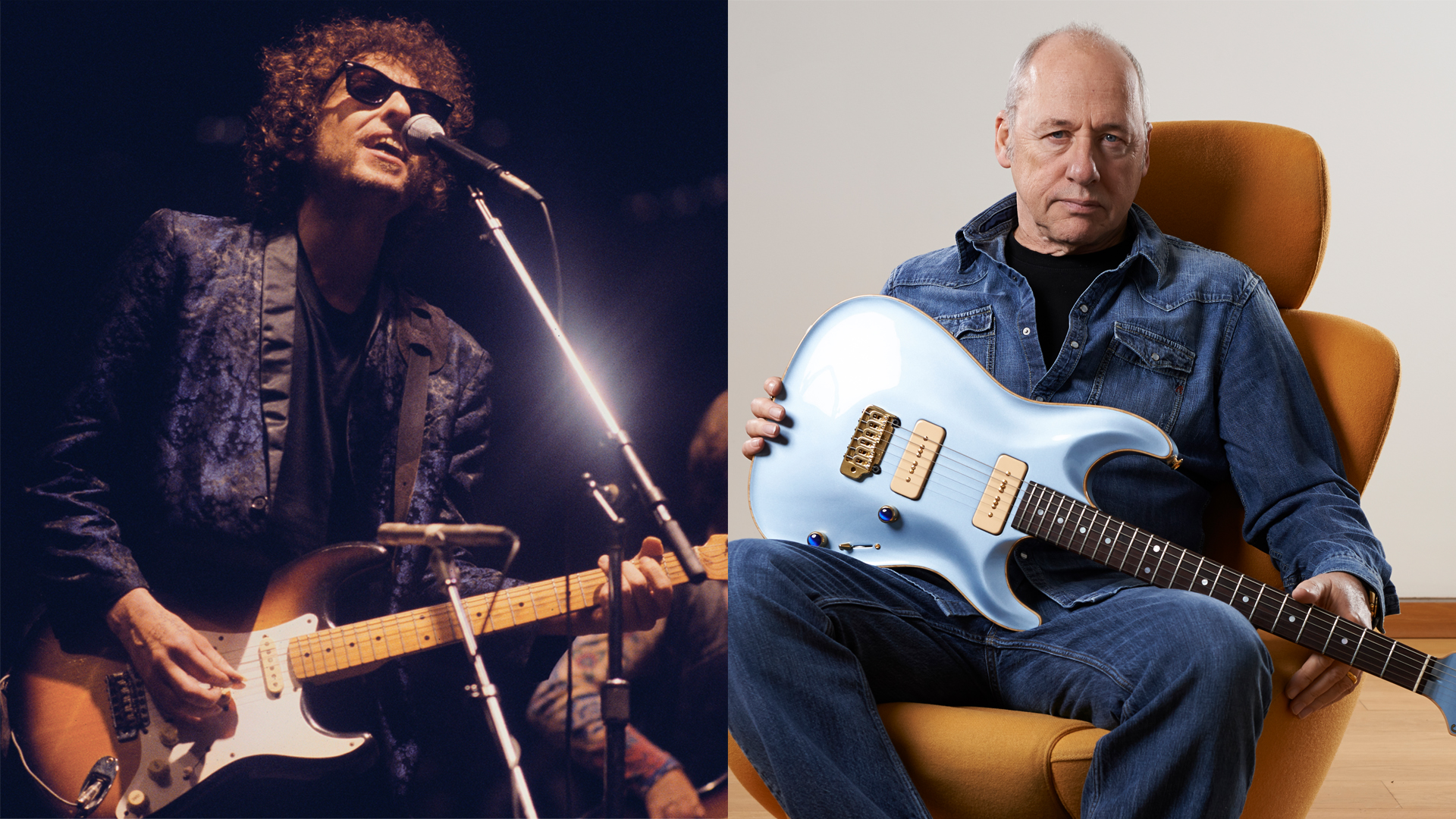

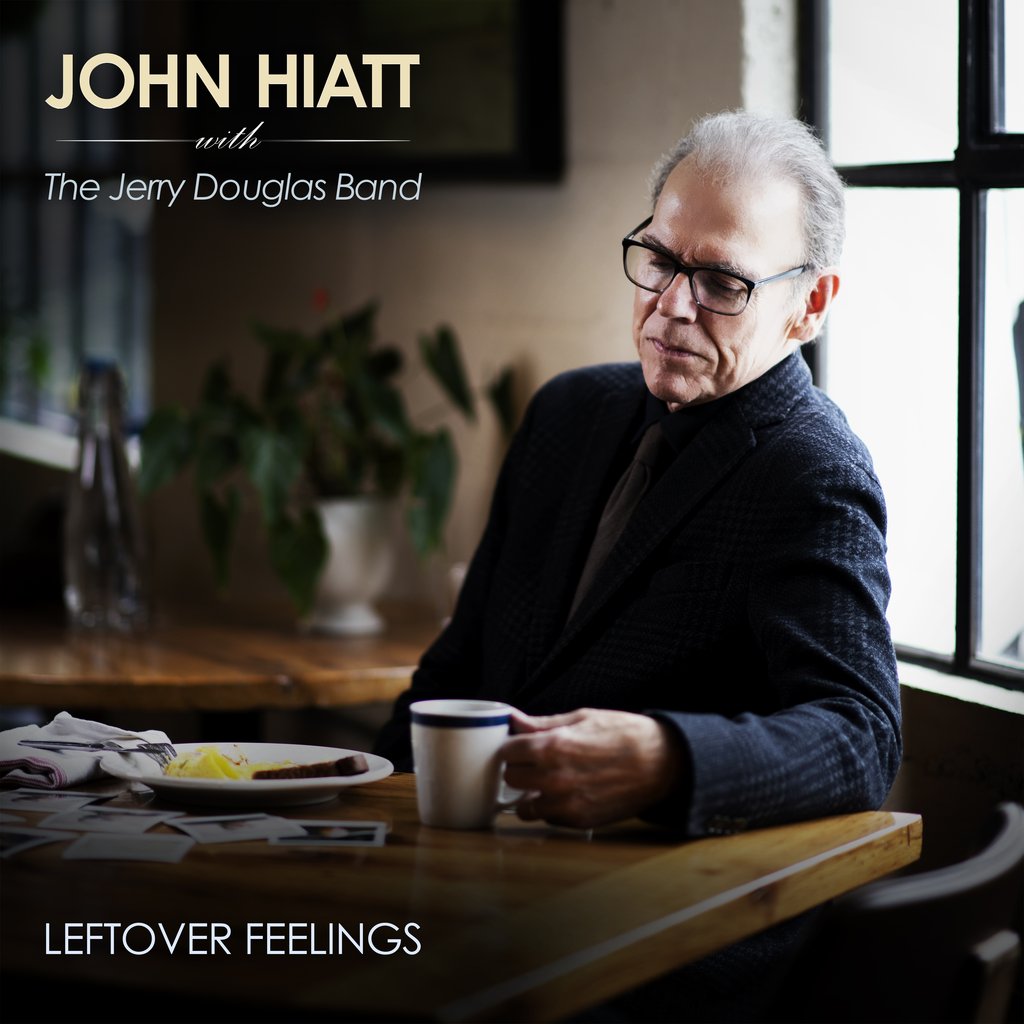

“We Were Halfway Into the Record Before We Realized There Wasn’t a Drummer on It”: John Hiatt Talks Songwriting and Recording His Latest Album 'Leftover Feelings' with the Jerry Douglas Band

Despite the pandemic the legendary songsmith gets under the red light of Nashville’s storied RCA Studio B.

A lot has changed since John Hiatt recorded The Eclipse Sessions in 2018, and his latest release, Leftover Feelings (New West), is all the more significant for a couple of reasons: It was made during the 2020 pandemic, and it was recorded at Nashville’s legendary RCA Studio B, during a time when tourists had virtually stopped visiting the historic site.

As Hiatt explains, “If the pandemic had any plusses, it was that we were able to get in there and record during the day. Normally you can only record at night at Studio B, and you have to break your gear down after each session. We got in there last October and we settled on four days. Every day we got tested, and when we were in the control room we wore masks and stayed apart and all that.”

It was worth the precautions to bring such a confluence of talent to bear on the project. Between the richness of Hiatt’s songs and the awesome musicianship of Jerry Douglas’s band – which includes Mike Seal on acoustic guitar and electric guitar, Daniel Kimbro on bass and Christian Sedelmyer on fiddle – Leftover Feelings is a superb, live-in-the-studio album that has the atmosphere of a very special room and the sense of togetherness that can only happen when players are in it as one.

However, it wasn’t a given that the project would actually take flight. “I think like everybody else I was initially just staying home, and I wasn’t terribly creative at all,” Hiatt says. “I was just fumbling around in the dark, doing some reading, but not really writing much.

“But after a while, I started writing some songs and making demos in my little home studio and got interested in that. Things that threaten life can also be life enhancing if you can turn them into something positive. To be able to make music during this time was just a miracle, and then to get together with Jerry and the guys and do the recording – we were just grinning ear to ear to be able to make music again after having not done it for a year.”

The album rolls out of the gate with “Long Black Electric Cadillac,” Hiatt’s whimsical nod to a “green” tail fin-festooned luxury ride. “I hope there will be a 1,000-mile battery in a long black electric Cadillac,” he says. “I’ll be first in line! It was fun to write that song and to start with something that had some levity. Then we head down to Mississippi [“Mississippi Phone Booth”] with another traveling song about a trip that a guy makes out of his personal hell, and he’s making the phone call home, saying, ‘Please don’t hang up on me this time!’”

Leftover Feelings is all about the light and dark contrasts in Hiatt’s stories, and so it follows that tracks like “Buddy Boy” and “Keen Rambler” offer respite to the album’s heavier songs, like “Light of the Burning Sun,” where he reveals the emotional weight of his brother’s suicide. “He was 21 and I was about 11,” Hiatt explains. “There were seven of us, and he was the oldest. So it’s the story of what happened and how it impacted the family, as suicide does. I was finally able to write a song about it.

I write songs as kind of a way to get my bearings at a certain point in my life, or maybe figure out things by telling stories.

John Hiatt

“I write songs as kind of a way to get my bearings at a certain point in my life, or maybe figure out things by telling stories. I figured it was bound to come up, and it was good to write about it. I was kind of reluctant to put it on the record, to be honest, because I thought it was too dark. But Jerry said, ‘Man, people have been through this and have lost loved ones this way, and they need to hear it.’”

How was the decision made to record the album at RCA Studio B?

It’s funny, because Ry Cooder and I had talked about doing a project there when he was here in 2019, and we went and looked at the studio. And then we thought maybe we should do it at FAME, down at Muscle Shoals. So we kind of logged that, but we crisscrossed paths and the songs didn’t come together for that project, and we put it on hold. And then I started talking to my manager about what we might want to do for a new record, and he said, “How about Jerry Douglas?”

I thought that was a fantastic idea, and so when that came up, I immediately thought RCA Studio B. Jerry played with Chet Atkins, and he’s done a lot of recording there. He came to Nashville in ’78, about eight years after I did. But I never recorded there. It’s funny, because I wrote for Tree Publishing, which was just up the street.

I rented a room in a boarding house with four or five other songwriters and paid 11 bucks a week for my spring bed, a hot plate and a bare light-bulb hanging down.

John Hiatt

When I came to town in 1970, the music business was on two streets: 16th Avenue South and 17th Avenue South. And all the publishing houses and all the studios, except RCA, were in houses. And next door to a publishing company would be a boarding house with six or eight songwriters living there. I lived just five blocks up the street from RCA, and my first year I rented a room in a boarding house with four or five other songwriters and paid 11 bucks a week for my spring bed, a hot plate and a bare light-bulb hanging down. I was writing songs and thinking I was all in it.

It’s interesting that you’ve come full circle to recording at a place that was once ground zero for country music.

When I got here, I didn’t write country songs and really didn’t know much about country music. Coming from Indianapolis, I wasn’t raised on it necessarily. I listened to AM radio as a kid. I knew Hank Williams and Jimmie Rodgers and some of that stuff, but I didn’t really know the depth of country music until I got out here and started getting schooled a little in what it was all about.

What was the live scene like in Nashville at that time?

The first year or two I was here, Tut Taylor, the great Dobro player, opened the Old Time Pickin’ Parlor, and people like Norman Blake, John Hartford and even Dylan played there. That was a place for acoustic music, and then I think, in ’70 or ’71, a couple of guys opened the Exit/In, and all of us sort of oddball singer-songwriters who had come to Nashville at the same time – guys like Chris Gantry, Jimmy Buffett and myself, who didn’t exactly fit the country-music mold – had a place to play.

I heard more great music there in the seven years I lived in Nashville, from ’70 to ’77. Everybody from Weather Report to Chick Corea to Larry Coryell and Eleventh House. I remember Billy Joel did one of his first gigs from Piano Man there, and I opened for him.

Did you rehearse much before recording, and were there any songs you worked on that didn’t end up on the album?

We only rehearsed once. I sent Jerry 16 or 17 songs, and he picked out 13 that he thought we should attempt. The guys made charts, and we got together and just ran ’em down. We didn’t want to get serious about any arrangement things; we just wanted to make sure sure we knew the songs when we went in to record.

So that took a day, and I think we went in two or three days later. We did cut an older song of mine called “Angel,” which was on the album Perfectly Good Guitar, and we recorded an acoustic version of “Slow Turning,” which didn’t make the record but may come out on something later. The first thing we cut was “Lilacs in Ohio.” I think we did three takes and everybody felt like we’ve got something going here.

It’s cool to hear a new version of that song, especially since there’s no drummer on this record. I didn’t even notice that right away, because the sound is so full.

You’re not the first person to say, “Jeez, we were halfway into the record before we realized there wasn’t a drummer on it.” I thought, Well that’s pretty good. Most of us stringed-instrument players fancy ourselves drummers anyway, so I think I kind of called it upfront and said, “Let’s just do it acoustically.”

I thought to just let the instruments speak, and it worked out pretty well. When this project came up, “Lilacs in Ohio” was the first thing I thought of in terms of being fun to redo and something that would lend itself to Jerry and his band. It was on Beneath This Gruff Exterior from 2003, so it’s been nearly 20 years since we did that rocking, four-piece combo version of it.

Songs to me are about telling stories.

John Hiatt

What originally inspired “Lilacs?” It’s quite different from anything you’ve written.

I stole the lyrics directly from a film called The Lost Weekend. It’s a black-and-white film made in the ’40s. Ray Milland plays a drunk, frustrated writer who can’t write the great book, and he sits at the bar and talks to Sam the bartender about it endlessly. In one of the scenes, he’s at the bar getting drunk and he’s talking about this woman he’s met and is infatuated with. He’s describing as he comes up to meet her in her building in New York City, and he says, “You notice how the gray of the light hits the gray of the drainpipe alongside her window. You’re there to have lunch with her, but she sends a note down regretting that she can’t come today, and you open the note and it smells like all the lilacs in Ohio.” And I thought, Man, what a beautiful image!

So I just stole the line and sort of told a fictitious story about a guy trying to write a book, and he’s trying to make time with this girl and his life’s a mess. So that’s where the story came from. You know, songs to me are about telling stories.

The album closes with “Sweet Dream,” which I’m guessing is a true story.

That’s kind of imagery from various trips I’ve taken crisscrossing the country over the years, and from hitchhiking when I was 17. I was actually up on Bear Mountain, and I was there the whole night because somebody had dropped me off on the old road and there was a new road that was sort of a bypass. It wasn’t until morning that I was picked up by the shoe salesman, as it says in one of the verses. So I used that imagery. It’s all about the sweet dreams that we hold on to in our passage through life. They are equal parts delightful and sometimes a little terrifying and scary.

It’s all about the sweet dreams that we hold on to in our passage through life. They are equal parts delightful and sometimes a little terrifying and scary.

John Hiatt

What guitars did you use in the studio?

I played one acoustic guitar the whole four days, a 1946 banner-head Gibson LG-2 that I bought two years ago. I miked it with a gray AEA re-creation of an RCA R44 ribbon microphone that [AEA founder] Wes Dooley has created so lovingly. That was also my vocal mic, but it also caught a lot of my acoustic guitar, so it was just a matter of getting the balance between it and a second mic on the guitar.

On a video of “Terms of My Surrender” you’re playing a PRS acoustic. What’s the story on that?

I have two that I really love: an Angelus and a Martin Simpson signature model that has a wider neck. I love the sound of PRS acoustics. Paul Smith is more known for his electrics, but I think this Martin Simpson model sounds fantastic. It’s got a big, fat neck for fingerpickers, and I play with my fingers.

I used a flat pick for years, but I just lost that ability. I’ll tell you what happened: For 10 years – from when I was 40 to 50 – I was at a very amateur level driving race cars on oval tracks around the south. One day, a buddy of mine and I were in the pits working on my car because I thought the cooling fan wan’t cooling the motor, and I stuck my index finger right into it, as if to point out this is what’s wrong, and the tip of the index finger on my right hand got shredded all to hell.

I went to the hospital and they stitched me up so that I have a Y-shape scar on the fingertip pad, and from that point on it didn’t feel right holding a flat pick, so I just started playing more with my fingers. Ry Cooder for years had tried to get me to do that. He said with the fingers you get better tone.

I just started playing more with my fingers. Ry Cooder for years had tried to get me to do that. He said with the fingers you get better tone.

John Hiatt

But anyway, once that happened somewhere in my mid-40s, I went to using my fingers, and I use them, I guess, in a somewhat unusual way. I take the thumb and index fingers as if I’m holding a pick and I downstroke with the index finger as if I’m flat picking. But then I upstroke with the thumbnail, so it’s back and forth, and then I add the second finger and get an even more rambling rhythmic thing going between the three fingers. It’s kind of a Reverend Gary Davis approach, but I don’t recommend sticking your finger into a cooling fan to have a similar result.

Buy Leftover Feelings here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Art Thompson is Senior Editor of Guitar Player magazine. He has authored stories with numerous guitar greats including B.B. King, Prince and Scotty Moore and interviewed gear innovators such as Paul Reed Smith, Randall Smith and Gary Kramer. He also wrote the first book on vintage effects pedals, Stompbox. Art's busy performance schedule with three stylistically diverse groups provides ample opportunity to test-drive new guitars, amps and effects, many of which are featured in the pages of GP.

“I knew he was going to be somebody then. He had that star quality”: Ritchie Blackmore on his first meeting with Jimmy Page and early recording sessions with Jeff Beck

“He used to send me to my room to practice my vibrato.” His father is the late Irish blues guitar great Gary Moore. But Jack Moore is cutting his own path with a Les Paul in his hands