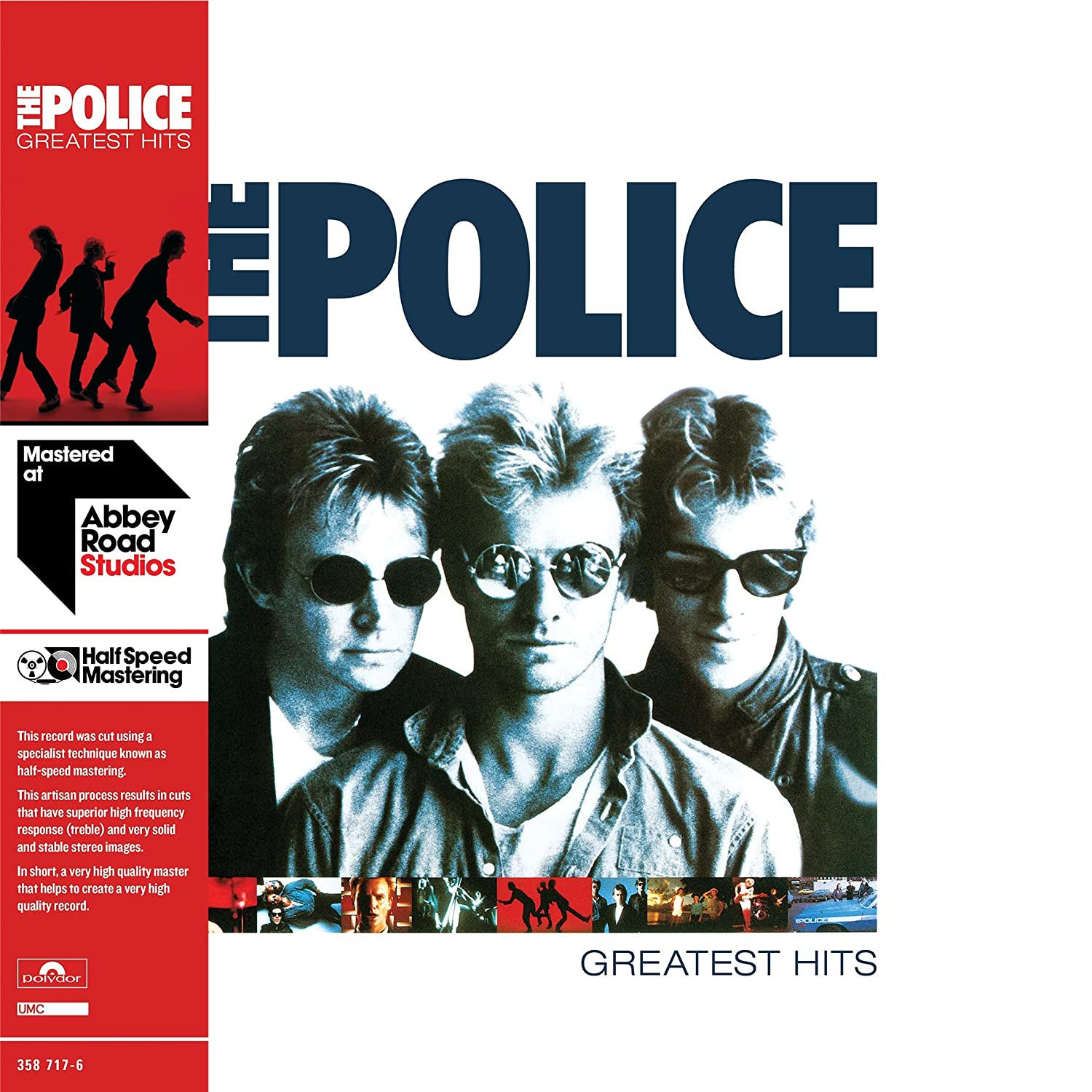

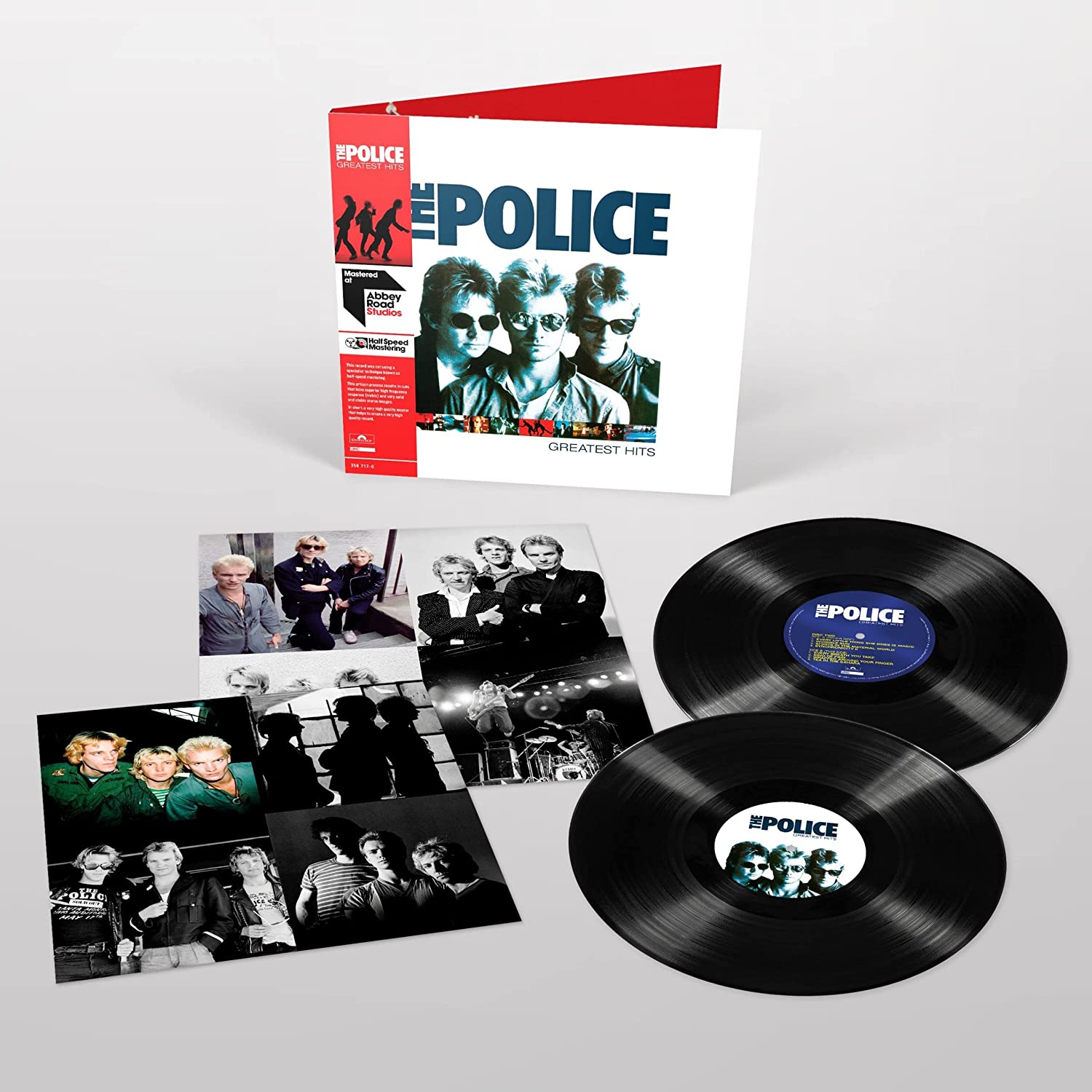

When it was issued in 1992, The Police – Greatest Hits became a multimillion seller on CD, but its availability on vinyl was limited.

To mark its 30-year anniversary, the 16-cut set (which, not surprisingly, packs in monsters like “Message in a Bottle,” “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic,” Every Breath You Take” and loads more) is getting the deluxe vinyl makeover.

Each track has been remastered at Abbey Road and cut at half-speed, and the package contains two heavyweight LPs and expanded artwork, along with other bells and whistles.

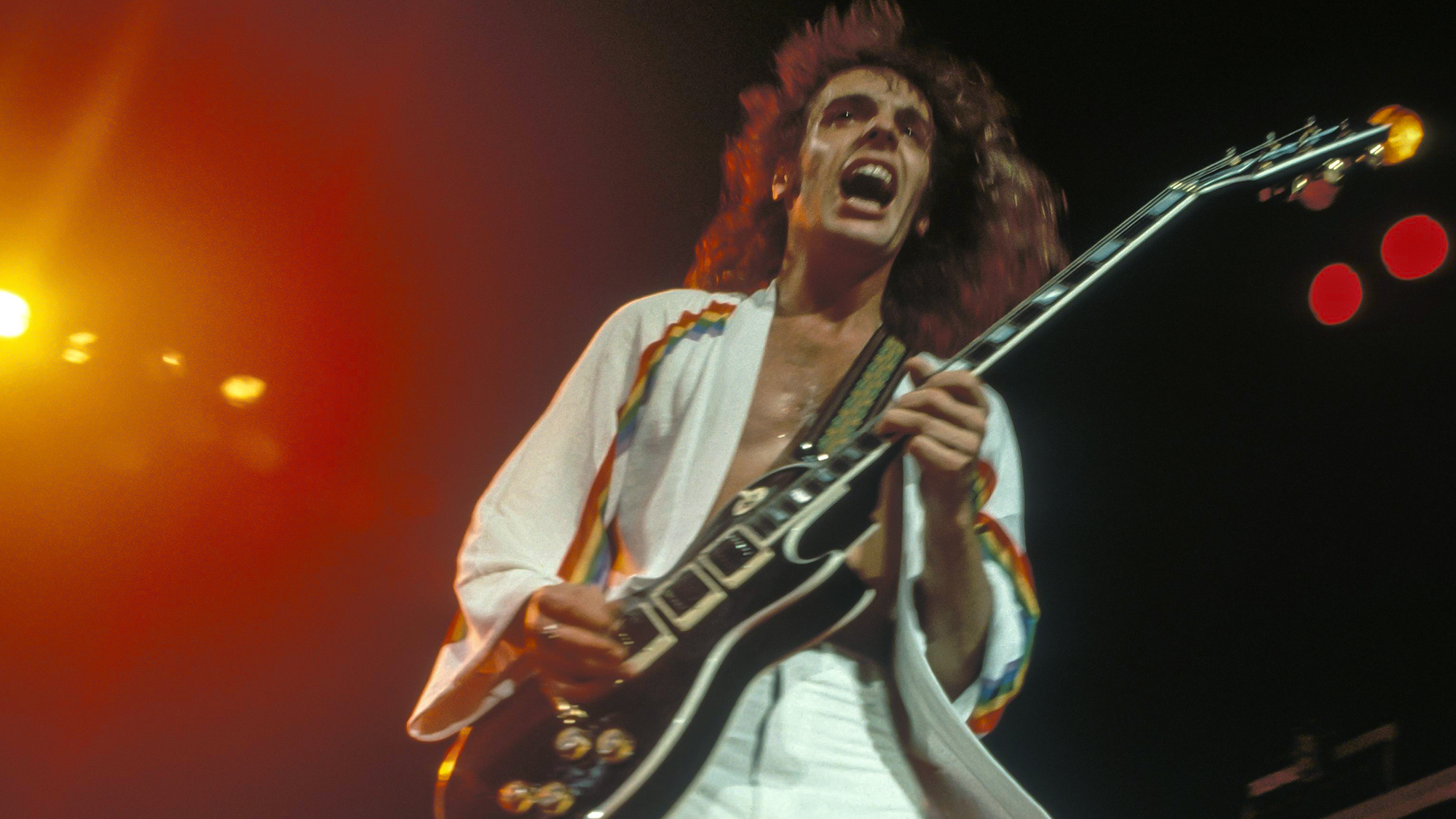

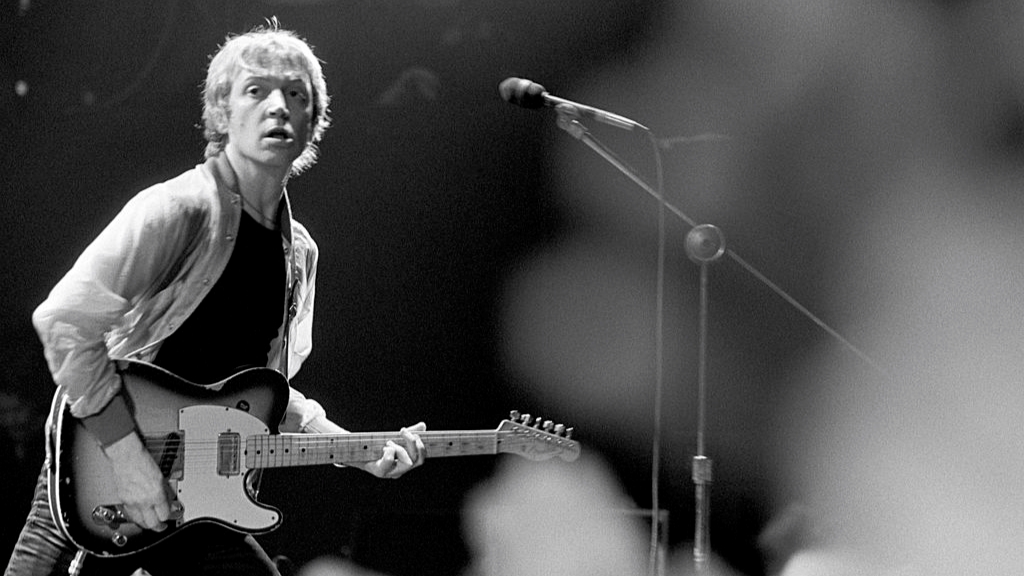

For guitarist Andy Summers, along with his former Police bandmates (bassist-singer Sting and drummer Stewart Copeland), approving remixes of tracks he recorded 40 years ago is all part of the job, but he’s enthusiastic about the new vinyl edition.

“It’s superior audio, so why wouldn’t we want it out?” he tells Guitar Player.

It’s superior audio

Andy Summers

He admits that listening to past work with the Police is the last thing he does on purpose, but on occasion he’ll hear a track while out in public, and his ears will perk up.

“It can happen at the weirdest times,” he reveals. “I’ll be in a bar in Mexico, and a Police song will come on, and I’ll go, ‘Wow, that’s really good.’ It’s interesting. You get away from something you did, and suddenly you’ll get a new take on it. It’s happened to me all over the world.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

In a remarkable career that lasted just under a decade – the trio formed in London in 1977 and called it quits in 1986 – the Police grew from a gritty pub-rock act that fused aggressive punk with elements of reggae to become a stadium-filling rock group that performed highly ambitious and sophisticated smash hits.

And unlike most bands that exist well past their shelf life, the trio didn’t stick around and start sucking.

They released five dynamite albums – Outlandos d’Amour, Reggatta de Blanc, Zenyatta Mondatta, Ghost in the Machine and Synchronicity – and left the building, their legacy complete and untarnished.

“There are so many reasons why we were a hit,” Summers tells us. “If I could narrow it down, I think the main thing about us was we didn’t sound like anybody else.

“It was something we were very conscious of. We didn’t want to sound like other bands. That was our natural instinct, but it could only have happened with the three of us. It’s a miracle of chemistry. If we were one person different, it would have been very different.”

Summers’ contribution to that chemistry cannot be overstated.

I think the main thing about us was we didn’t sound like anybody else

Andy Summers

By the time he joined the Police, he was already fully formed as a player, having studied classical and jazz guitar, and he boasted a performing resume on both sides of the Atlantic (for a brief time, he was a member of Eric Burdon and the Animals).

With the Police, he dispensed with the blues-based licks and rote solos so prevalent in the ’70s and pioneered a crafty blend of minimalism built around tight but memorable riffs (played mainly on a 1961 Telecaster), shimmering chord voicings and an individualistic use of pedal effects that magnified the band’s sound in ways that were both thrilling and mysterious.

“I was a fairly trained guitarist, but I needed to open things up onstage,” Summers says.

“For me, the pedal thing started with the [MXR] Phase 90. We were playing for an hour, hour and a half, and there was just the three of us – we didn’t have keyboards to fall back on. I had to make the guitar sound interesting, and then these pedals turned up.

“I added more pedals and worked out all sorts of combinations. Before long, I had a big Pete Cornish pedalboard with eight or nine boxes, but it basically started with the Phase 90.”

By the time of the Police’s second album, 1979’s Reggatta de Blanc, his playing style and sound began to infiltrate the lexicon of other guitarists, a trend he became keenly aware of.

“We were a hot item, and people saw how successful we were, and yes, I certainly noticed a lot of players aping – I’ll say ‘copying’ – me,” he says.

“We were so popular and everybody thought, That’s how to get a hot sound. But that’s just where my ear went.”

Part of the freshness of what we did was because the tracks were so stripped down

Andy Summers

The Police’s lean-and-mean ethos extended to their studio recordings, and even when they enjoyed lavish budgets and were able to work in the spiffiest facilities in the world (Synchronicity was cut at George Martin’s AIR Studios in Montserrat), they resisted the temptation to overburden their songs with superfluous instrumentation.

“That was a trap we were aware of,” Summers says. “We started as a punk band, which lasted about five minutes because we weren’t really punks, but I think part of the freshness of what we did was because the tracks were so stripped down.

“I never got into the army of guitars. The music was made out of the actual parts we were playing instead of multitracking. We tried to keep things as close as we could to the trio sound, and that made it easy for me to play the songs onstage, because I wasn’t missing six parts.”

He pauses, then adds with a laugh, “Of course, you have to be talented to do that. You have to be good.”

1. “Message In a Bottle” by the Police from Reggatta De Blanc (1979)

“Sting showed me the riff he had, but I embellished it. I had the chops to make it swing and rock. I could tell right away it had something, and I was thrilled to play something that started to progress our style.

“Rather than just strumming chords – C# minor, A, B, F# minor – I was outlining the figures in a way that integrated very well with Stewart’s hi-hat. I should say that the recorded version of this song is the best drum track Stewart ever did.

“In the studio, we added a second guitar part, so there’s a harmony going on there. Then it goes into a more of a rock chorus, but the verse is the classic Police sound, again outlining the chord, which is tonic, fifth and added ninth.

“I overdubbed some soloing. We were coming out of a sort of religious punk scene, and guitar solos at that time were supposed to be a mark of the old guard. Stewart was vehement about that, but I was a great soloist, so of course I was soloing my ass off.

I was thrilled to play something that started to progress our style

Andy Summers

“We were always in a weird position with that. As I started playing a solo over the end of the song, Sting went, ‘Oh, actually, this is really good. Keep it in, keep it in.’ It wasn’t up really loud, which I would’ve liked, but it was in there, with a lot of feeling.

“It’s a famous riff, and I have to admit, it’s hard to play. People want to play it, but a lot of them can’t – the stretches are too big. You have to be a real guitarist to do it well.

“I’ve played it a lot of different ways, in a lot of different positions, over the years, just trying to do stuff with it, sometimes playing the second chord, the A with the open A string, rather than going to the obvious sort of shape of the added-ninth chord. It’s pretty cool.”

2. “Bring On the Night” by the Police from Reggatta De Blanc (1979)

“It has that fingerpicked verse section. One thing that Sting and I shared was a love for classical guitar. As it turned out, I’d played classical guitar for years – I studied it for years at school in America.

“Once Sting and I got together, I discovered that he was a bit of a nut for classical guitar, as well. I would often play him classical guitar pieces – [Heitor] Villa-Lobos or some Bach – because I knew the stuff very well.

“He came up with this little pattern in A minor that was very easy for me to play – it was sort of in A minor and all over an A note. He had the part, but of course, I could play it. It wasn’t standard rock at all.

It wasn’t standard rock at all

Andy Summers

“I liked the atmosphere of the song. I put in that muted opening part before the main verse section. We played it like that in concert a lot. The solo of the song is rather striking. None of it was worked out beforehand. It was all sort of spontaneous, really, just me in the moment.

“It seemed like the appropriate, anguished response to the lyrics of the song. We kept all the noises in. I supposed that was our punk ethos coming in. You can’t be all po-faced about all of this.”

3. “Reggatta De Blanc” by the Police from Reggatta De Blanc (1979)

“It came about from jamming onstage. We didn’t have a lot of material at the time, so we had to stretch things out. Toward the end of our show, we’d play ‘Can’t Stand Losing You,’ and then we’d have this huge jam in the middle where I would play all sorts of stuff on the guitar. I used the Echoplex a lot.

“Sting and I would do this droning D pedal. It would go on for a while, and I’d do all these harmonics at the seventh fret and different whammy things. I learned the harmonics thing from Lenny Breau in Nashville. He was one of the greatest guitarists ever.

“Over time, this jam developed. Sting started doing some sort of incantatory thing to the audience, and we’d all be changing along together. Stewart was wailing on the hi-hat. We would build things up and get ready, and at the appropriate moment we would take off on that B to A movement.

It was our thing, so to get a Grammy for something that had grown so organically out of our sweat onstage, it was very satisfying

Andy Summers

“I would hit the fuzz and play this little riff, and we’d have thousands of people going nuts. You didn’t need to do more than that if your feel was right. We were very locked in as a unit, so we could come up with this stuff. It was great fun.

“We won a Grammy for that song. I mean, it’s true that we were very popular and could have just said ‘hello’ and gotten an award for it. But I was quite pleased about it, actually, because that piece of music was very typical of our trio.

“It was our thing, so to get a Grammy for something that had grown so organically out of our sweat onstage, it was very satisfying. And, of course, it didn’t sound like anything else.”

4. “De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da” by the Police from Zenyatta Mondatta (1980)

“By this point, we had the Police’s stylistic approach pretty much nailed down. It didn’t matter what the chord structure was or what kind of music we were playing; we could make it sound like the Police.

“On ‘De Do Do Do,’ I do a slightly rhythmic approach to playing the chords as opposed to just banging them out. I sort of fingerpicked the outlines of each chord, which made it sound different.

“I think this was a factor in making our songs endure. If you played them with big barre chords, they would sound old and ordinary.

By this point, we had the Police’s stylistic approach pretty much nailed down

Andy Summers

“One thing in particular I would do is avoid a major or minor third in favor of a second. This song starts on an A chord, but I wouldn’t play the C# of A major. Instead, I’d play B, which is the second of that scale.

“I’d pluck between the fifth string, third string or fourth string with a slightly damped upstroke picking pattern. This was typical of what I’d do. It made the parts more interesting and less corny.

“We were recording pretty quickly, but I didn’t want to rush through my parts. I do this solo over kind of a weird section, and I knew I needed to work it out rather than just improvise it in one go.

“I said to Sting and Stewart, ‘Give me half an hour to come up with something.’ It worked out pretty well.”

5. “Driven to Tears” by the Police from Zenyatta Mondatta (1980)

“It’s quite a complicated arrangement. We’d have these creative jams, and Sting would eventually start wailing on the top and I’d play all kinds of stuff. They weren’t conventional guitar solos, but they were these big sounds and some passages, all kinds of stuff.

“With this song, I don’t think we did play it onstage before we recorded it; I think we just did it on the spot. It’s a classic situation where, six months after you record it, you go, ‘Oh, shit. I wish we’d done that when we recorded it.’ I know we played it a few different ways, moving it up and back in keys.

“I’m pretty sure I used my Telecaster. I had my amp on 11 for the solo – it was really loud, because it sounded appropriate for that sort of dissonant, chromatic solo. But I didn’t play standard blues guitar licks, which would’ve brought it down.

“It had to be something angry because of the lyrical content, which is basically about war and suffering.

I didn’t play standard blues guitar licks, which would’ve brought it down

Andy Summers

“Feedback in the studio has always been an interesting technical thing. You don’t want to stand in front of the amp; you have to sort of contrive a way to get the sound while standing away from the amp so you don’t get your ears blasted.

“I think it was done in one take. We all heard it and went, ‘That’s it. It’s got it.’ I never played it onstage the same way twice. That’s kind of a prog-rock thing, where all the solos are completely worked out and rehearsed note for note.

“We were very loose onstage. Songs got extended, not in a fussy way, but in a way that just kind of expanded their scope. I think that made things more exciting.”

Order the new The Police – Greatest Hits deluxe vinyl release here.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.