“We All Try to Copy the People We Love... But You Have to Believe in Yourself”: Bill Frisell and John Scofield Talk Developing Your Own Style

The jazz guitar legends dish out some timeless advice in this classic interview from the ‘Guitar Player’ vault.

***The following interview excerpt originally appeared in the July 1992 issue of Guitar Player***

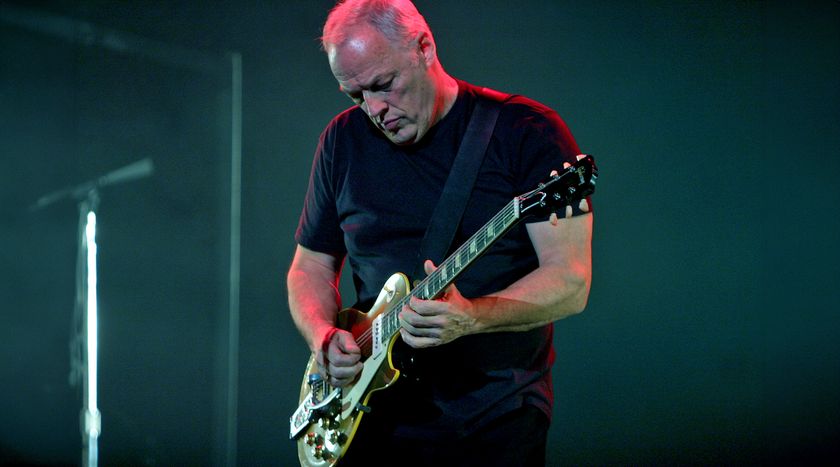

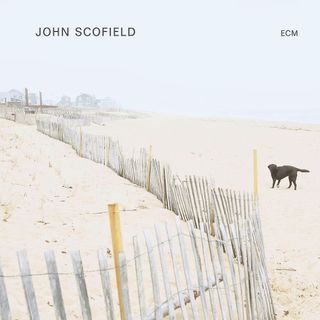

World renowned for his work with Miles Davis's early-'80s ensembles, John Scofield remains at the top echelon of jazz guitar players, performing with Joe Lovano and dishing out superb records like Time on My Hands and 1991's Meant to Be.

In fact, Sco may be the king of post-rock bebop electric guitar. Originally inspired by the early-'60s British rock invasion, he dove into the improvised linear waterfalls of John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk and Charlie Parker, surfacing with a uniquely lyrical single-note integrity and a wicked knack for "that swing."

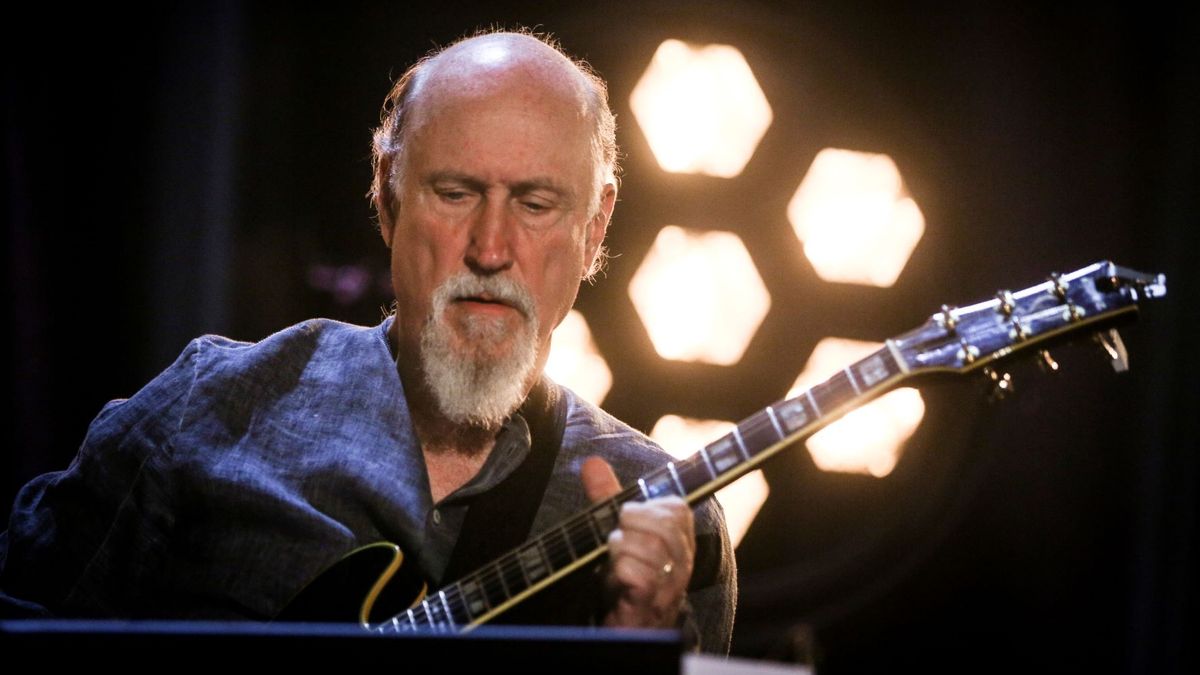

The perfect counterpoint to that linearity is Bill Frisell, whose credits only begin with John Zorn's Naked City, Paul Motian, Vernon Reid and Paul Bley. Frisell created what even John Scofield calls "the most unique concept in guitar today."

Seemingly oblivious (or wisely wary) of categories, Frisell draws naturally on his entire consciousness of music and sound. Intelligent, warm and imaginative, his earlier ECM outings and recent Elektra/Nonesuch records with the Bill Frisell Band – Is That You?, Before We Were Born, and Where in the World? – reveal a complex and deeply human musical personality.

The title "colorist" is far too limited – his music conjures the many unseen sides of melody and emotion, and does so with the depth and purity of a mature musician.

Right now Bill's system is fighting impurities in the form of a nagging cold, and Sco has just shaken off bronchitis. But when the music begins, the real world fades as line artist and painter, structuralist and texture man, merge in the harmonic pool of the rehearsal room.

Here, all labels are unreadable; as Sco eases in fat chords with a twist of his volume knob, Frisell roars into mazelike fuzz lines that spin out into muted purrs.

A few days later, with Grace Under Pressure in the can, the two musicians relax together over coffee on a small hotel room couch. Their personalities speak volumes about their sounds.

Looking you dead in the eye, Scofield is animated and articulate, the educated product of an East Coast background.

Surveying the room, Frisell is shy in an endearing way, with a studied Midwestern care to his explanations.

But both men speak of common influences, common eras and a mutually uncommon love for the art of improvisation.

There's a lot of talk about "new traditionalism" in jazz, but the two of you seem to be moving in an organic, less defined direction.

Frisell: It's hard to deny all the things that have happened on the guitar in the last 30 or 40 years. If I played a saxophone or trumpet, it would be a lot easier to fall into this classicism, whereas with guitar, you could just do a Wes Montgomery thing.

But if you're my age and grew up with the Beatles, Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix, you'd have to be more blatant.

Scofield: Both of us were at that age when the shit really changed, when white America completely embraced rock and roll. The Rolling Stones came over in 1964-1965, when I was just 13, and people were into jazz and blues and folk music and all that.

All of a sudden it was on TV, on Ed Sullivan – it overtook every kid's life. And it was rock and roll with country elements and blues elements, but everybody at that time was affected by it.

If there are young neoclassicists, it's easier for them because they are choosing to do one thing out of the past. But the reason I play the guitar – and I imagine why Bill did – was because there was great stuff on the radio.

I'm not a rock and roll player, and neither is Bill. But we were very influenced by that period

John Scofield

I'm not a rock and roll player, and neither is Bill. But we were very influenced by that period. Both of us went to Berklee and wanted to be jazz guys. I went for a while with a big fat guitar, trying to sound like Jim Hall or Jimmy Raney or Wes Montgomery. But in the back of my mind I remembered B.B. King or Jeff Beck or Jimi Hendrix – this other sound.

Do you create a distinction between rock and jazz, or have the two genres, as in Naked City or Miles's band, become interdependent?

Frisell: Well, now I don't. There was a period when I had my fat guitar, an exact copy of Jim Hall's ES-175. And that was an incredibly valuable period, to really immerse myself in the harmonies. That's where all the building blocks of what I do now came from.

But then at a certain point this little bell went off and something just hit me: What I was doing wasn't honest. It was 1971, and I was pretending it was still 1956.

Scofield: On guitar, it seemed obvious to use the sounds of rock and roll in jazz. Why it hadn't been done before was because guys like Jim Hall didn't have it available – they didn't have that background.

When you develop on your instrument, you develop a sound, and that stays with you your whole life. Even though Miles Davis played electric music, he was still playing the trumpet with the sound he worked on for years.

When you develop on your instrument, you develop a sound, and that stays with you your whole life

John Scofield

So should Jim Hall get a fuzztone and play light strings and use a volume pedal? No, he's got his style, and that's what you get after developing. It's a chronological thing.

For me it seemed like the obvious thing to do. At some point, we thought, "Why not use those things in a jazz context?"

Do you think that guitar innovation is simply a matter of shifting elements from the past, or can a new musical vocabulary be created? Where is jazz guitar going?

Scofield: You know the Jaco story, right? When an interviewer asked him, "Where is jazz bass going today?" he got up and said, "It's going to the bathroom right now." [laughs]

Scofield: We all try to copy the people we love, and we learn from them, but you have to believe in yourself. If you open yourself up and let music come out, it's you.

The great thing about the guitar in jazz, especially for me and Bill, is there weren't as many greats back then. There were really only a few. And certain developments that happened in rock and roll guitar and country-western guitar and classical guitar were available for us to use to make ourselves sound different.

Where does the past leave you? Is it a burden or a blessing?

Frisell: It's a necessity – you've got to check it out. It's just a responsibility. If you're going to play, you'd better check out what was going on before.

If you're going to play, you'd better check out what was going on before

Bill Frisell

This can get really philosophical: What are you? Are you unto yourself or are you part of the cosmic universal soul, which is probably more the truth. You've got to believe that this stuff comes through you and whatever comes out, you have to let it happen.

The next generation will get something from that, just because you're you. The people that we all love were special. Any great musician has that thing that's just them, and you accept people's deficiencies. You accept deficiencies in yourself and work on your strong points.

Bill just plays music, and he's not limited by "bebop," "rock," "country," or "classical." Everybody's so into categories, and I am too, because we have to talk about it, right? But after a certain point it just becomes use your imagination. It's just music.

Let that sound inside you come out. That's what every great musician has done. Don't bother thinking about whether it's this or that.

You can order John Scofield’s latest album (above) here.

Don't miss our Guitar Player Presents John Scofield event this Thursday, April 14, in San Francisco.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

A former editor at Guitar Player and Guitar World, and an ex-member of Humble Pie, Mr. Bungle and French band AIR, author James Volpe Rotondi plays guitar for the acclaimed Led Zeppelin tribute, ZOSO, which The L.A. Times has called “head and shoulders above all other Led Zeppelin tribute bands.” Find JVR on Instagram at @james.volpe.rotondi, on the web at JVRonGTR.com, and look for upcoming tour dates at zosoontour.com

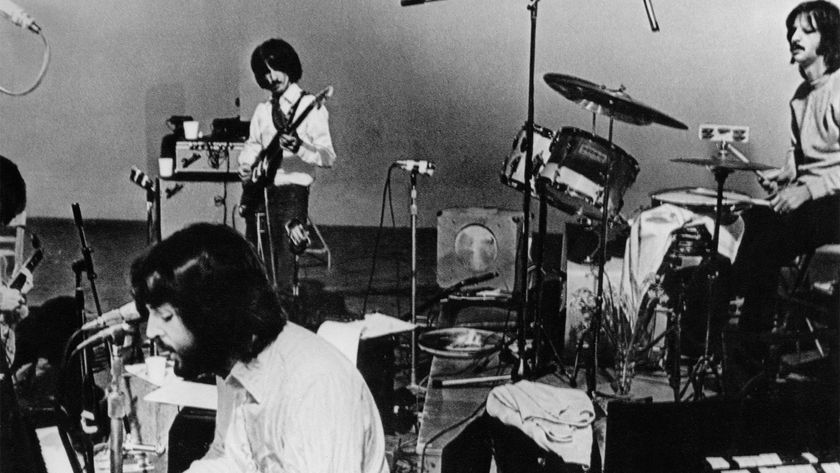

"I wrote it in five minutes the night before.” How a candid moment caught on camera became the final Beatles song the band recorded together

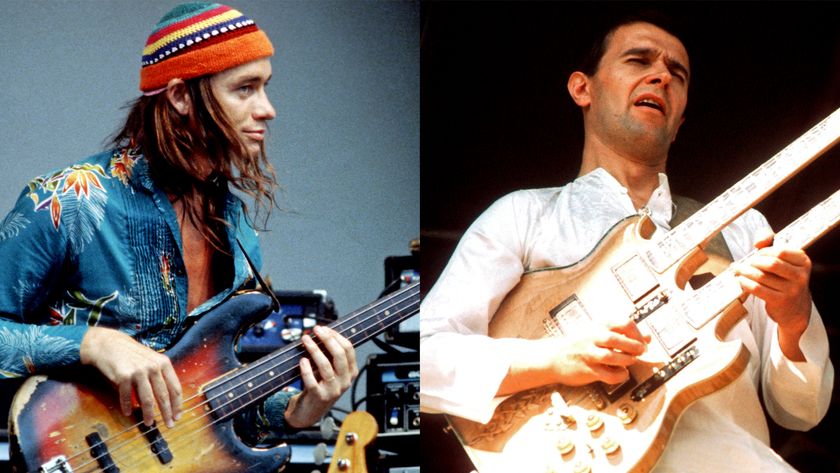

"Jaco thought he was gonna die that day in the control room of CBS! Tony was furious." John McLaughlin on Jaco Pastorius, Tony Williams, and the short and tumultuous reign of the Trio of Doom