Watch Jimmy Page Spin Link Wray’s Groundbreaking “Rumble” Single

The guitar hero of guitar heroes was a hard rock progenitor.

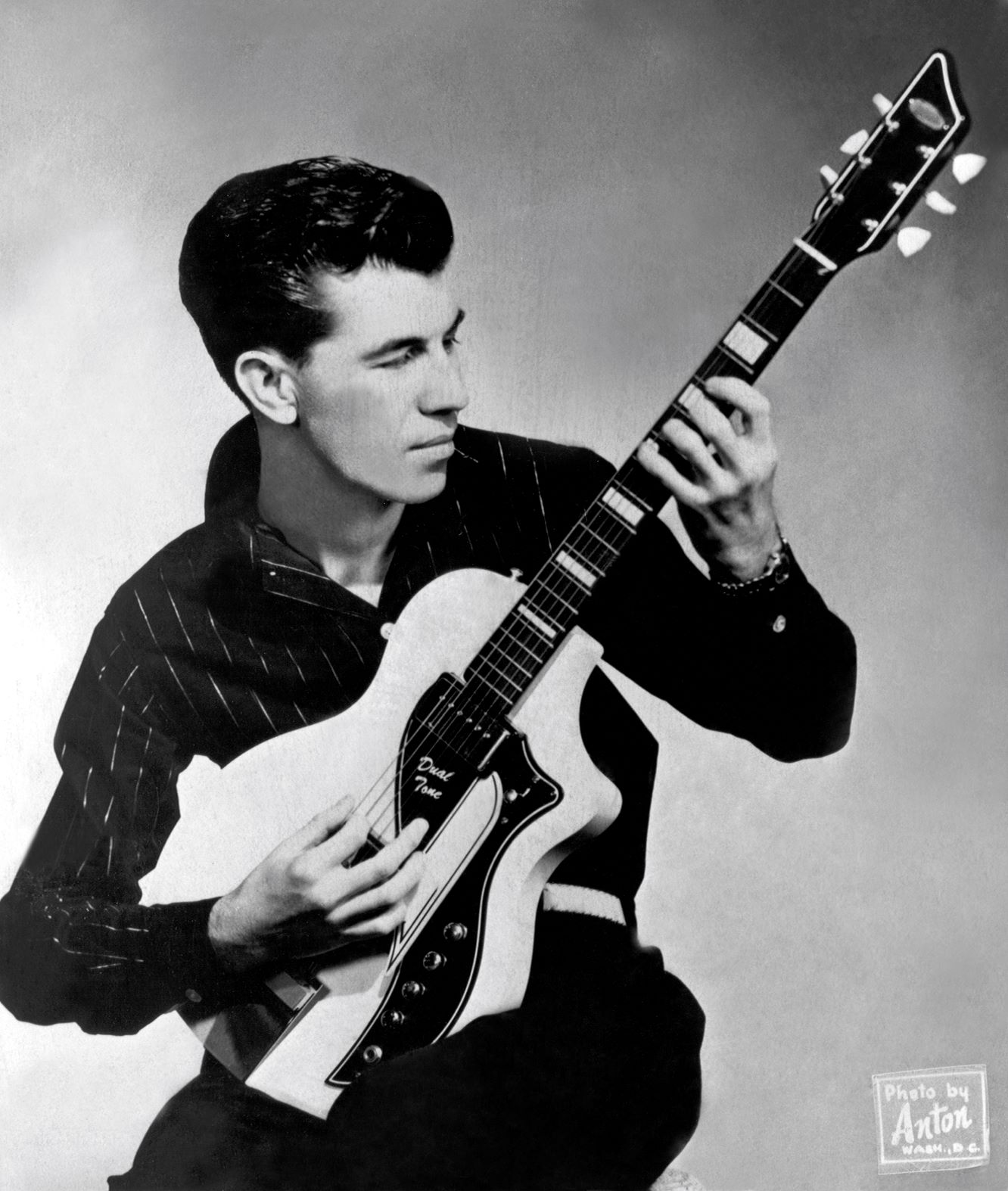

On this day, in 2005, the guitar world lost one its most groundbreaking and influential artists, Frederick Lincoln Wray, Jr. aka Link Wray. Though Wray released many critically acclaimed recordings throughout the course of his decades-long career he is widely known for his 1958 hit “Rumble.”

A tense, brooding electric guitar instrumental that swings from prowling open chord distortion to a violent outburst of frenetic strumming and back again “Rumble” has often been cited as a missing link between blues and hard rock.

Like many other career-defining tracks such as Black Sabbath’s “Paranoid” and ZZ Top’s “Tush,” Link Wray & His Ray Men’s “Rumble” came together extremely fast – in this case during an impromptu stage request.

While performing at a record hop in Fredericksburg, Virginia in 1957, pioneering rock ‘n’ roll deejay Milt Grant requested Wray and his band play a ‘stroll’ (a popular rockabilly dance of the late ‘50s) in order to introduce the Diamonds – a band who were at the time riding high on the success of their hit “The Stroll.”

Though Wray was not au fait with the number and felt unsure how to kick things off, his younger brother, Doug, quickly sprang into action with a drum beat. Suddenly, inspiration struck like a bolt of lightning and Wray’s iconic Dsus2/E riff was born.

Spiced up with a cheeky B7 and a descending E minor pentatonic lick it’s the epitome of cowboy chord cool.

Wray’s older brother, Ray, then grabbed the vocal mic and placed it in front of the guitarist’s cranked Premier amp. Saturated in natural distortion and pulsating with tremolo the souped-up sound drove the audience wild.

“The only mic they had back in those days was just the singer’s – they didn’t mic the amps or anything,” recalled Wray. “You couldn’t even hear [bassist] Shorty, and Doug was playing so loud because he was playing with the butt ends of his sticks, so all you could really hear was me and Doug.

“And the kids, they just went ape and were screaming over me… We had to play it about four times for the kids. They kept hollering and screaming, banging on the stage, “Play that weird song! Play that weird song!”

“That weird song” (also referred to by Wray as “Oddball”) was released the following March titled “Rumble.”

Clocking in at just under two-and-a-half minutes, this short, sharp shock of rock was immediately powerful enough to get itself banned on radio – inevitably adding to its kudos and mystique.

Down the line, countless guitar players have been quoted as fans of this game-changing, career-breaking classic, including Bob Dylan (“'Rumble' is the best instrumental ever”) and Pete Townshend ("If it hadn't been for Link Wray and ‘Rumble,' I would have never picked up a guitar.”)

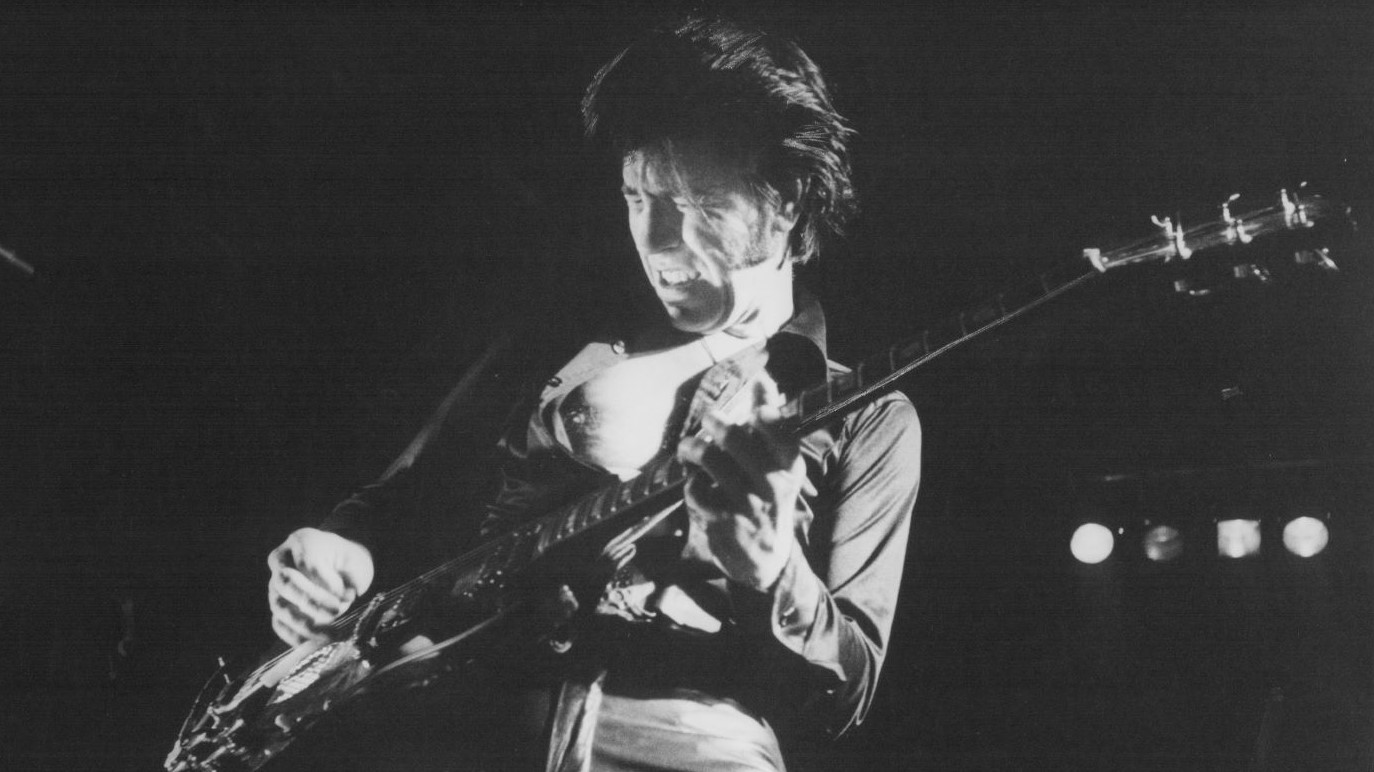

And in this clip from the brilliant 2008 documentary It Might Get Loud, Jimmy Page can be seen listening to this landmark seven-inch immersed in reverence. “I listened to anything with guitar on when I was a kid that was being played,” he tells Jack White and the Edge.

“But the first time I heard “Rumble” – that was something that had so much profound attitude to it… It really does.”

Browse Link Wray's catalog here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Rod Brakes is a music journalist with an expertise in guitars. Having spent many years at the coalface as a guitar dealer and tech, Rod's more recent work as a writer covering artists, industry pros and gear includes contributions for leading publications and websites such as Guitarist, Total Guitar, Guitar World, Guitar Player and MusicRadar in addition to specialist music books, blogs and social media. He is also a lifelong musician.

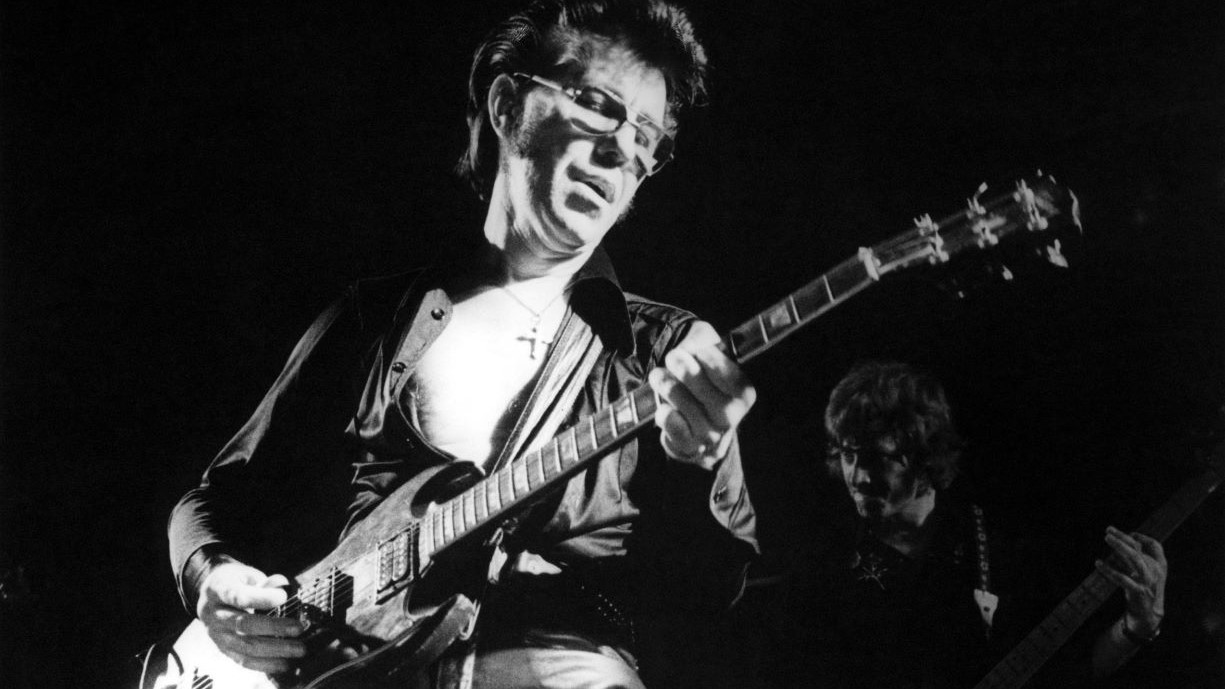

“He used to send me to my room to practice my vibrato.” His father is the late Irish blues guitar great Gary Moore. But Jack Moore is cutting his own path with a Les Paul in his hands

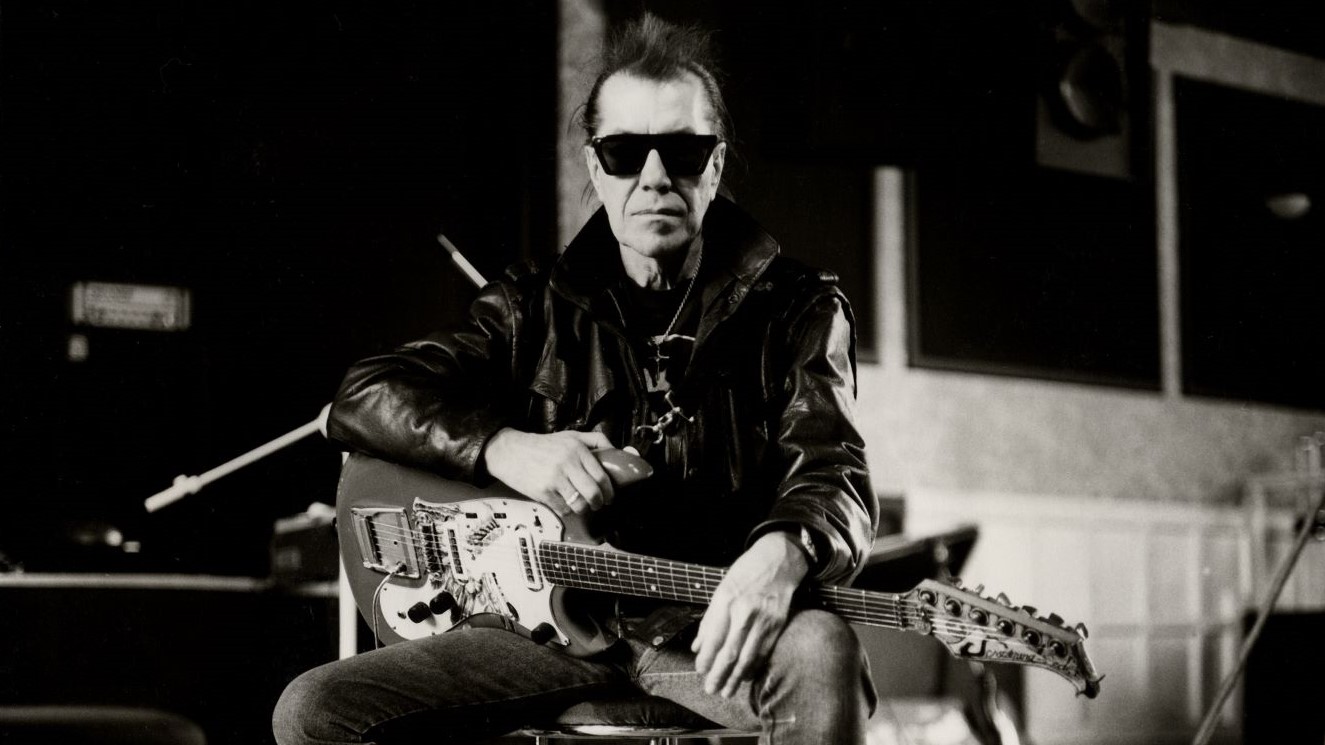

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue