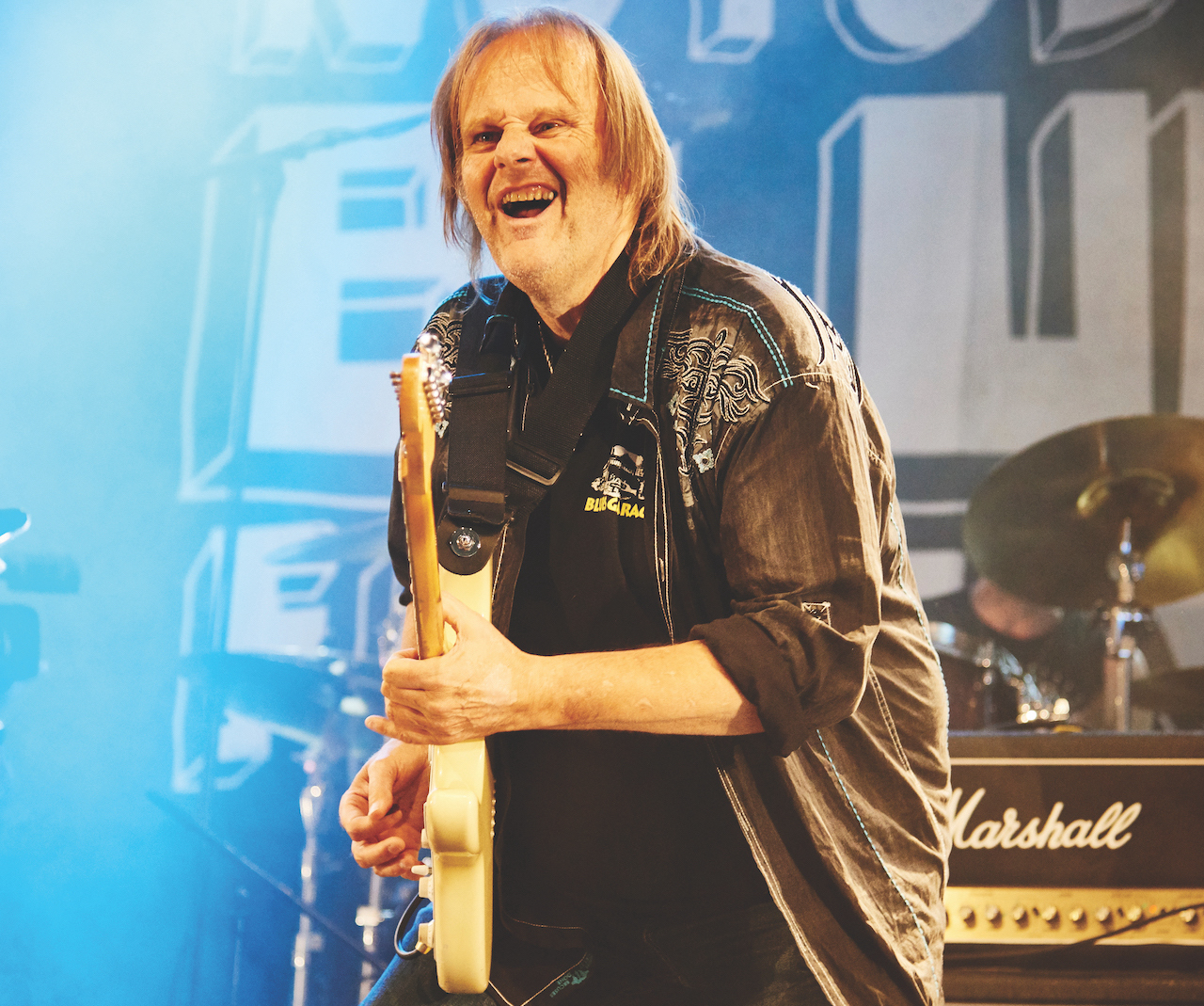

“My old Strat weighs more than a Les Paul that I have, but my signature model is so light that you can hold it up with your pinkie”: Walter Trout is healthier and playing better than ever, but he’s still being dragged down by the world around him

On Broken, Trout – with some help from Dee Snider and a ’60s Coral electric sitar – tries to bring hope in a divided world through some of the most fiery licks of his career

“It’s a rough time,” veteran blues guitarist Walter Trout attests. “The whole world feels like it’s in a dark place, with the wars going on. In this country, the political polarization definitely feels like we’re very divided. It feels like a very scary time for the world.”

That sense of fear was heavy on Trout’s mind as he set out to write the dozen tracks on Broken (Mascot), his 21st solo album since he left John Mayall’s band in 1989. But far from wallowing in dread, Trout’s new songs take the listener on a journey out of the darkness and into redemptive light.

“I feel like we’re at a pivotal moment in world history,” he tells Guitar Player. “Which way are we going to go, you know? I think there’s some concern that’s reflected on this album, but I believe that the overall theme, by the end of the record, is that there’s still some hope. I’ve got to hold on to hope.”

Trout sounds convincingly committed to that goal on Broken. The energy, passion and fire that he brings to his playing, both live and on the new record, belie the fact that just 10 years ago he underwent a liver transplant that saved his life but left him unable to play guitar, which he had to relearn from scratch. His emotively expressive fretwork on Broken fulfills all the expectations set by his stellar past work, but the record throws a few curveballs into the mix as well.

“I tried a couple of new approaches and went a little out of the box on this record,” Trout explains. “And I’m really excited about how well it turned out.”

Powered by the album’s hard-rocking lead single, Talking to Myself, Broken debuted at the top of the Billboard Blues chart. Adding to his pleasure at the news, Trout says the outlook for his health remains positive.

“I get monitored at UCLA Liver Clinic, and every few months I go in for blood tests,” he says. “They said that I was probably at the healthiest that I’ve ever been in my whole life. I feel like I’m a young man again. I’m full of energy and have the cholesterol count of a marathon runner. I’m doing great, man, so hopefully I can keep doing this and I’ve got a few more records in me.”

There’s quite a somber tone to Broken. Even the title sounds a little bleak.

“When I make a record, I sequester myself for two weeks and I write all the songs. I’m not a guy who can sit in the hotel and write songs while I’m on the road; I have to concentrate and get myself in a certain zone, and it’s really good that I’m not around people at that point.

If someone tells me a ’70s Strat is no good, I’ll say, ‘Well, here’s what I can do with it’

“During the writing process for this album, I’d been watching the news, and I was getting myself into a certain frame of mind. And then – boom – they all came out. I guess maybe there was a theme. When I wrote [2020’s] Ordinary Madness, there was a lot on there that related to mental illness and therapy, which I’ve been through in my life. With [2022’s] Ride, when I listened to it, I realized that almost the whole album was about my childhood.

“And I think Broken is really about the state of the world. With the track Broken, I wasn’t really thinking about the world; I was thinking about my years as a heroin addict and an alcoholic and being homeless, and also a lot of friends of mine dying from overdoses. That sort of turned into a metaphor for the world, with all these wars going on.”

The sequencing of the tracks takes the listener through quite a journey, as the more positive, upbeat tracks kick in to switch the overall feel of the album.

“You’re exactly right there. I’m glad you picked up on that. I sequenced the album with my wife, Marie, and Eric Corne, my producer. We’re trying to take the listener on a rollercoaster ride. That’s what I try to do in my live shows as well.”

Do the songs change much between writing them and putting them down in the studio with the band?

“On the last few albums, I rehearsed the songs with the band for a few days before we went into the studio. I have an amazing band of top-rate musicians, and they always have great suggestions about how we should put things together.

“Once we get into the studio, Eric will have some great ideas as well. He’s a great musician and a Grammy-nominated songwriter. I’m happy to take ideas onboard, although if I feel strongly about something I will insist on what I want, as I do have a certain vision and idea of what I want the song to sound like. We work very quickly in the studio these days, since everything is mostly arranged by the time we get there.”

When I was in a country band we were playing Mama Tried, which has a four-note lick that starts the song. It has to be played exactly the same every night, and by the fourth night I started fucking it up because I have to play completely spontaneously – the way I feel something – every night

Lead single Talking To Myself moves away from the blues-rock vibe heard on much of the album.

“You’re exactly right. I was in my car, listening to a radio station that was playing hits from the ’60s, from when I was a teenager: the Buckinghams, Paul Revere, the Byrds, the early electric Bob Dylan and The Band. I thought to myself that I wanted to try to write something in that vein – something that would sound right if you were listening to AM radio in your car in 1967.

“The lyrics came after being fed up with people ranting on social media. When the track was finished, I was unsure how to approach the solo, and I said I thought it needed an electric sitar. Thomas Ross Johansen, who owned the studio and played keyboards on many of the tracks, said, ‘Give me an hour,’ and sure enough, an hour later, a friend of his brought a ’60s Coral electric sitar to the studio. I just played it once for the solo, and that was it.”

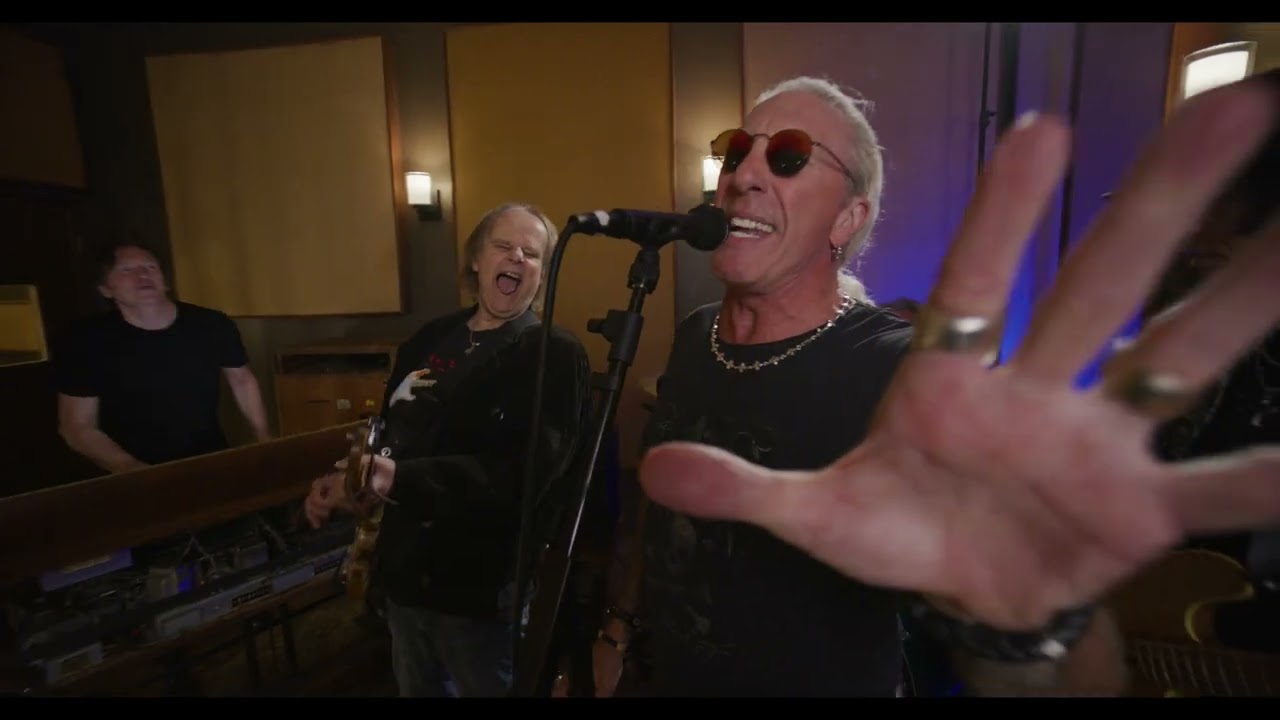

Dee Snider, an unlikely guest, is on I’ve Had Enough, which is a great, pounding rocker.

“I had a blast doing this with him. He’s an amazing, knowledgeable man. He’s nothing like what you might think if you only know Twisted Sister. We’re friends, and he sent me a message saying, ‘How about if I sing a track on your album?’ I thought, ‘If I’m going to have a rock icon on my record, I’m going to have to write a rock song.’

“This is another one where I was watching the news on TV while I was writing the album and I switched it off, thinking, ‘Fuck this, I’ve had enough.’ And then a lightbulb went on in my head. [laughs] Ten minutes later, I had the lyrics.”

Breathe is another song that deviates from the blues-rock template, taking a strong country-fueled approach.

“I was thinking of the Faces when I recorded this one. The solo was just recorded live with the band while we laid the track down. I figured I needed to approach things differently, rather than play blues licks. When I was very young, I played a lot of traditional country music.”

When you put a strongly melodic statement solo like that down, will you reproduce it live?

“There’s no way I can do that live – I’ve never been able to play the same thing more than once. Even way back when I was in a country band, at 19 years old, we were playing a song by Merle Haggard called Mama Tried, which has a four-note lick that starts the song. It has to be played exactly the same every night, and by the fourth night I started fucking it up because I have to play completely spontaneously – the way I feel something – every night. That’s one of the joys for me, to be able to play spontaneously and freely in the moment – that sense of release.”

Heaven or Hell has great lyrics, almost like something Raymond Chandler would write.

“That’s great. [laughs] I really like that comparison. They were inspired by a talk I had with a blind street preacher in the U.K. a long time ago. But more recently, I saw some southern preacher on TV saying anyone who allows their son to become trans should be shot in the head and gay people should be eradicated from the face of the earth.

“These are people purporting to be Christians. If you firmly believe in heaven and hell and you’re preaching the murder of gay and trans people, then you’re going to hell, if you believe in that concept. My kid, Biscuit, is nonbinary and that bigotry and pure hatred really outrages me. They’ve completely missed the point. Religion should not be about hate.

“My son, Jon, plays guitar on this one as well. In fact, I have a lot of family connections on this record. My wife, Marie, co-wrote a number of lyrics. Jon’s partner, Vera Armbruster, plays classical harp. They’re both in the Royal Conservatory of Music in Denmark, and she played harp on Love of My Life. And finally, my middle child, Biscuit, wrote the last track on the album, Falls Apart, as well as doing the vocal arrangement for it and singing background vocals.”

What were your go-to guitars and amps for the album?

“I mainly used a Delaney Guitars Walter Trout model. Most of the album was recorded with that, which is also the guitar that I use on tour. Anything else was my 1973 Fender Strat, which is the guitar that the signature model was based on. The amp that I used was my old Mesa/Boogie Mark IV for every track. So one amp and two guitars. [laughs] I can just blow through everything with that.”

Was the Delaney intended to be a clone of your old Strat?

“Yeah. Michael Delaney did a magnificent job. The one thing that he changed, at my request, was the weight. My old Strat weighs more than a Les Paul that I have. One of the main reasons that I can’t use it onstage is that my shoulders can’t take the weight anymore. The signature model is so light that you can hold it up with your pinkie.”

Is there much difference in sound between the two guitars?

“They’re actually very close. He really tried to replicate the sound of the guitar. My old Strat does have something unique about it. I bought it off the shelf in 1973, and I’m the only person who’s ever owned it.”

For many people, the early ’70s Strats are the least fashionable and desirable models.

“Absolutely. When people tell me what’s good or not good, I always think, ‘I’ll make up my own mind.’ I remember going to see Little Feat in the early ’70s, and Lowell George was using a brand-new guitar. I never saw Jimi Hendrix playing a ’50s Strat. It’s my own opinion, but I think that all that vintage guitar stuff is bullshit. If someone tells me a ’70s Strat is no good, I’ll say, ‘Well, here’s what I can fucking do with it.’” [laughs]

You mentioned to me a couple of years ago that you’d been watching a few things on YouTube during lockdown, including how to sweep pick like Yngwie. Did you ever find a place to utilize that in your music?

“No. In fact I’ve actually gone in the opposite direction. I’ve moved toward much simpler, strong melodic statements in my soloing. I play less notes these days, but they all mean a lot more.”

- Walter Trout's Broken can be streamed or purchased now.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.

“I knew he was going to be somebody then. He had that star quality”: Ritchie Blackmore on his first meeting with Jimmy Page and early recording sessions with Jeff Beck

“He used to send me to my room to practice my vibrato.” His father is the late Irish blues guitar great Gary Moore. But Jack Moore is cutting his own path with a Les Paul in his hands