“Use It Like a Paintbrush, Not a Machine”: John Frusciante On the Art of Guitar Playing

This classic Red Hot Chili Peppers interview from the GP vault captures the Magik in the minds of Flea and Frusciante as they reflect upon their 1991 masterpiece.

Right now, the Red Hot Chili Peppers are on the road following the release of their latest studio album, Unlimited Love.

Nowadays, the band are able to pack out stadiums the world over, but it wasn’t always that way.

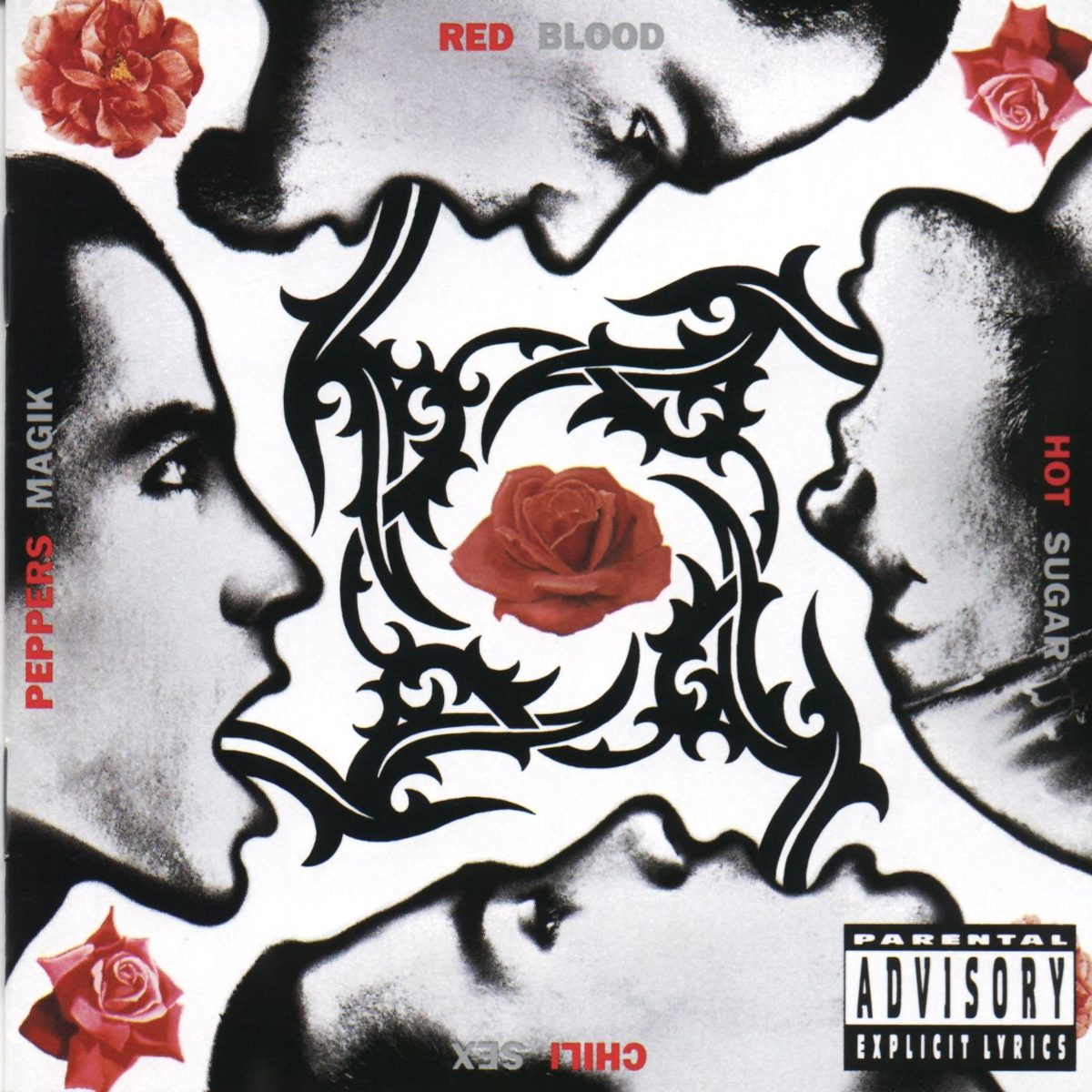

Indeed, the Red Hot Chili Peppers had been together for the best part of a decade before 1991’s Blood Sugar Sex Magik catapulted them to stratospheric heights of worldwide success.

To some extent, the Chili Peppers’ previous album – 1989’s Mother’s Milk – served as a runup to the era-defining masterpiece that followed.

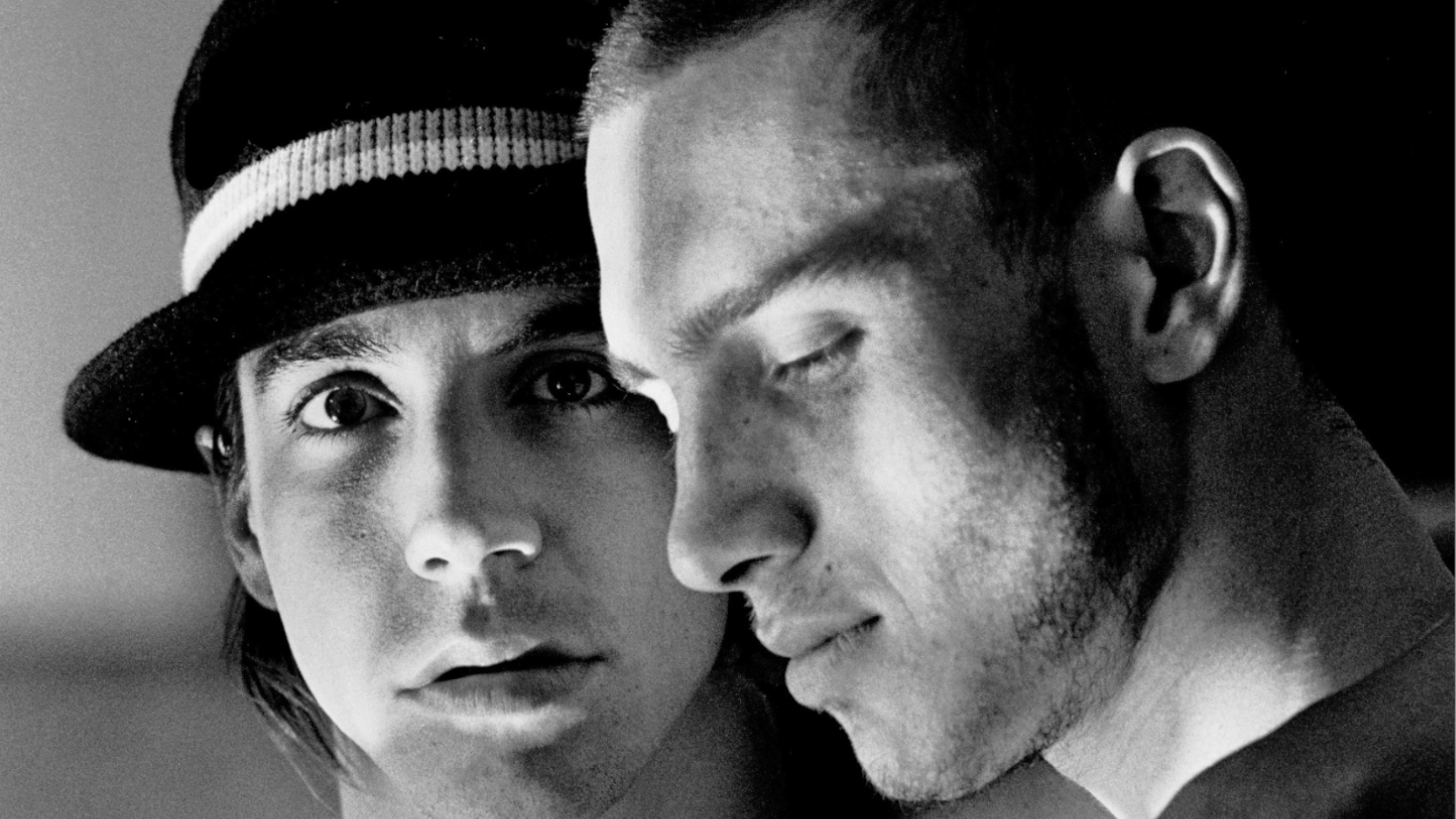

By 1991, the classic lineup that formed in 1988 – comprising guitarist John Frusciante, bassist Flea, drummer Chad Smith and vocalist Anthony Kiedis – was fully forged. That few years spent honing their craft together had solidified the band into a musical phenomenon greater than the sum of its parts.

Furthermore, Frusciante had developed significantly as an artist in his own right.

And though it would have been difficult for him to appreciate at the time, the 21-year-old wunderkind would ultimately go down in music history as one of the most important and influential guitar players of his generation.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

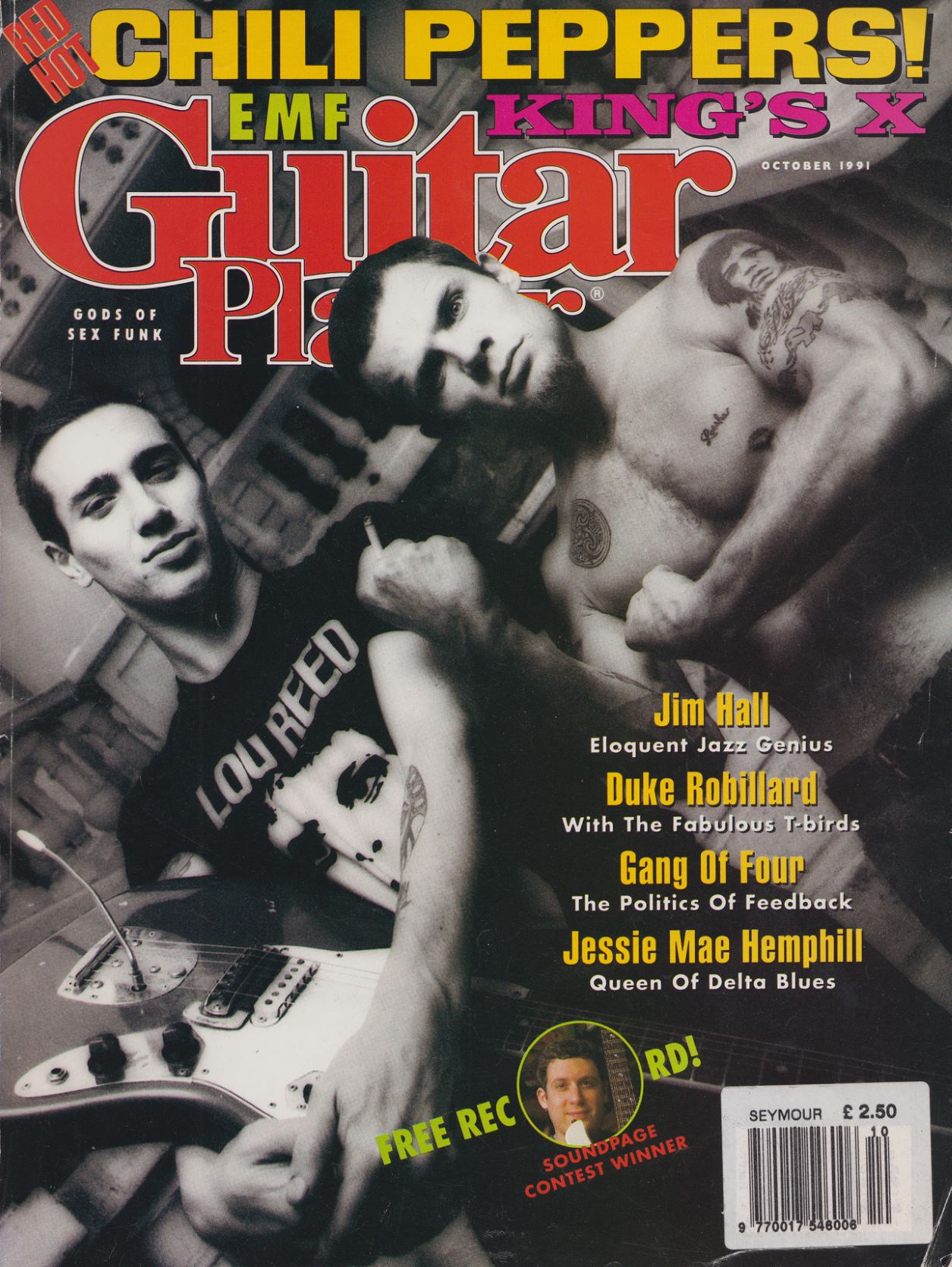

The following interview extract originally appeared in the October 1991 issue of Guitar Player…

“This is not a commercial studio,” says John Frusciante as he ascends the creaking staircase. Right – as if anyone could mistake the ramshackle Spanish-style mansion for a conventional recording facility.

“We rented the place for a few months and moved in our own gear. It cost the same as if we’d gone into a regular studio.

“The house is haunted,” adds the guitarist.

He indicates a candle-lit alcove off the second-floor landing.

“I was sleeping right here about a week after we moved in, and I heard the sound of a woman having sex, but there was definitely no woman in the house. And other people who worked on the project have seen things.”

The beautiful but decaying hacienda in Hollywood’s Laurel Canyon has been the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ home for the last two months.

“We sleep here, eat here, and every day we just wake up and start recording,” says John. “It’s a chance not many artists get – to not have to think about bills, answering phones, or shaking hands we don’t feel like shaking.”

Frusciante leads the way through a huge parlor, stopping to strike a single chord on a piano that probably hasn’t been tuned since talkies came in.

As the sour notes echo against the bare walls and hardwood floor, he outlines the band’s recording procedure: “We all play together facing each other downstairs in the living room. The board is in the next room over, and we mike all our amps down in the basement.”

John indicates a cement deck on the grassy hillside behind the house. “That’s where we recorded our rendition of Robert Johnson’s ‘They’re Red Hot.’ We ran cables up there, and Chad played drums with his hands. I think our version is almost as freaky by today’s standards as Johnson’s version was by his.”

Instead of looking through a window at three sweaty guys frowning in the control room, we’re looking out at trees and flowers

John Frusciante

The tour concludes in Frusciante’s bedroom, bare except for mattress, ghetto blaster and CDs, a few of John’s paintings and scribbles on the wall courtesy of bassist Flea’s young daughter.

“I recorded the acoustic guitars right here, and Anthony does all his vocals from his bedroom. Instead of looking through a window at three sweaty guys frowning in the control room, we’re looking out at trees and flowers.”

Judging by the assortment of rough and final mixes this writer heard, simple, well-focused living and a no-nonsense producer have done wonders for the Chili Peppers’ music.

The band’s fifth album (tentatively titled Blood Sugar Sex Magik) is a giant step forward for the group, a record that’s paradoxically rawer yet more sophisticated than any of the Peppers’ previous work.

Producer Rick Rubin’s unapologetically blunt approach makes no concession to prevailing rock production strategies. He captures all the blood and sweat of real musicians pounding the hell out of their instruments.

The true-to-life instrumental tones aren’t pumped up with digital steroids, and every song blasts from the speakers with naked, soulful ferocity.

John reveals a mature, egoless style that belies his 21 years

But for all its audio vérité viciousness, the new material boasts a new level of ensemble sensitivity. Once-hyperactive parts have been pared down, revealing remarkable interplay and dynamics.

Flea, 28, largely abandons his trademark jackhammer slapping for fresh, understated lines, while John reveals a mature, egoless style that belies his 21 years.

For the first time, the Peppers scale the heights of funkiness attained by their long-time models, groove bands such as P-Funk, the Meters, and Sly & The Family Stone.

But the Chilis haven’t sacrificed their over-the-top humor and intensity.

The Peppers may now be the foremost practitioners of that near-extinct species, body music that moves to a human heartbeat.

“Nothing was recorded to a click,” insists Flea, and it shows: the group’s organic tempo fluctuations and near-telepathic polyrhythmic interplay evoke the great groove traditions of the ‘60s and ‘70s, but with a relentless ‘90s edge.

Those who have previously dismissed the Chili Peppers as abrasive, unmusical clowns are in for a big surprise.

John Frusciante: I’m so psyched! This is the fastest we’ve ever done a record. We zipped right though the basics, 25 songs. We were tight as hell – we totally got inside each other’s heads and became one being.

Our music is so much more colorful than in the past, and I’m so happy about it. I never took anything so seriously in my life.

Flea: John is playing much freer and thinking less. I loved John’s playing on Mother’s Milk, but now he’s so pure and spontaneous.

He never considers doing something again and again – he’ll just record maybe one overdub. He likes capturing the natural feeling on tape.

Almost all the solos are first takes

John Frusciante

Frusciante: Almost all the solos are first takes and some of them were cut along with the basics, like “My Lovely Man” and the first solo on “Funky Monks.”

On “Funky Monks” I played everything without a pick, even the solo. I’ve been playing that way more and more lately – in fact, I haven’t used a pick in weeks now.

The “Funky Monks” solo is very rhythmically free.

Frusciante: Yeah, I was thinking “rubber band.” I’ve gotten more into those kinds of rhythms, because they sound more natural than really straight stuff.

The second part of the solo is one of the few fast parts on the album. I thought of it as a parody of a rock star solo.

The intro has electric guitars not plugged in, just miked acoustically. It’s the same thing Dave Navarro of Jane’s Addiction does on “Been Caught Stealing,” though Snakefinger did it first.

Flea’s playing is much more subtle. There’s more groove, less flash.

Flea: I consciously avoided anything busy or fancy. I tried to get small enough to get inside the song, as opposed to stepping out and saying, “Hey, I’m Flea, the bitchin’ bass player.”

I can play fast things that make bass players say “Wow!” but it’s better to imply your technique with something simple.

After you’ve heard a million bass players rip off Flea’s slap thing, what’s the point of continuing to do it?

John Frusciante

Frusciante: You can get just as many “wows” that way. And after you’ve heard a million bass players rip off Flea’s slap thing, what’s the point of continuing to do it?

Flea: I hardly slap at all on the new record, aside from “Naked in the Rain.” You know, I was reading this Bass Player interview with Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth, who I really respect. She said she loved funk bass but hated the way white guys play it, because they’ve turned it into this macho-jock thing.

As I read that, I knew I was responsible for that tendency. But on the new record I don’t do any of that – I try to play simply and beautifully. And I hope she doesn’t hate me, ‘cause I think she’s great.

Having a relatively stable lineup seems to have benefited your music.

Flea: Between our first record [Red Hot Chili Peppers] and our second [Freaky Styley], our guitarist and drummer quit.

Between the third album [The Uplift Mofo Party Plan] and the fourth [Mother’s Milk], Hillel Slovak, our guitarist and dear friend, died.

This was the first time we’ve made two albums with the same band.

Frusciante: No – Mother’s Milk was Anthony Kiedis, John Frusciante, Chad Smith, and Flea; this album is the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

‘Mother’s Milk’ was Anthony Kiedis, John Frusciante, Chad Smith, and Flea; this album is the Red Hot Chili Peppers

John Frusciante

It’s an entity made by the four of us jumping out of our bodies into a cosmic swell. We’ve all grown out of love and admiration for each other.

Some might call the punk-funk crossover you’ve popularized a trend.

Flea: Sometimes I hear music that we’ve influenced and think it’s being taken to a great place. Other times I think people only see the superficial aspects of our band.

I influenced a lot of white rock bassists with my athletic-style playing. After our last record all these long-haired metal guys started coming to our shows, and now it’s turned into this whole fast slapathon.

Frusciante: Axl Rose told us that Guns ‘N Roses had the Chili Peppers in mind when they did “Rocket Queen.”

Flea: And Extreme’s “Get the Funk Out” is a huge Chili Pepper rip-off. But it’s so slick and glossy – there’s no dirt in it. It sounds like a studio creation. It’s the most unfunky shit I ever heard.

Frusciante: I got into character for this record the same way an actor would prepare for a part. I wouldn’t have anything to do with anything that didn’t involve positive vibrations for the creative spirit of the band.

That applied to people as well as things like clocks, garbage cans, and ugly lights. If I knew there was going to be an Arsenio Hall billboard coming up down the street, I’d turn away from it so I didn’t have to see it.

I tried hard to expose myself to humor and creativity of all types: film, paintings, music.

What music inspires you?

Frusciante: My favorite guitarists: Eddie Hazel from P-Funk, Robert Johnson, James Williamson of the Stooges, Snakefinger, D. Boon from the Minutemen, Lightin’ Hopkins, Leadbelly, Tom Verlaine, Danny Whitten from Crazy Horse, and Zander Schloss and Dix Denney from Thelonious Monster.

The most important inspiration is undoubtedly Zoot Horn Rollo’s playing on Captain Beefheart’s ‘Trout Mask Replica’

John Frusciante

But the most important inspiration is undoubtedly Zoot Horn Rollo’s playing on Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica. If I listen to it first thing in the morning, I’m assure a day of unbridled creativity.

What do those players have in common?

Frusciante: They weren’t thinking about coming off as cool guys – they just played every note like it meant something.

A lot of people don’t understand how much it means to just beat the shit out of your guitar, to put every last ounce of energy and spirit into it. You should use it like a paintbrush, not a machine. It’s there for you to express yourself on.

Flea: John’s attitude is really pure, a reminder to me of why I started doing this in the first place. He gets the big picture so well, in terms of being able to love John Coltrane and two-chord punk rock with equal fervor.

The band’s musical philosophy seems largely based on perceiving those connections.

Flea: There are only two categories in music: soulful and non-soulful. Anything that has human emotion and spirit and is played with heart and sincerity is really happening.

We can see the beauty in Eric Dolphy, the Ramones, and everything in between. We love anything that has a groove that makes you want to live.

If you have an open mind, you can see the beauty in all kinds of music.

There are only two categories in music: soulful and non-soulful

Flea

Frusciante: Not just music. Robert De Niro and Harpo Marx have influenced me as much as any guitar player. Think of how De Niro only says things that need to be said. He drops the unnecessary lines and gets his message across with small facial movements.

The lesson for a guitarist is that you don’t have to play a million notes, all really loud.

And Harpo, the funniest person who ever lived, said everything with facial expressions and noises. Every single gesture really meant something, and all of that translates musically.

Flea: The best thing I did to prepare for the record was to lose my phone book and break my foot, both of which happened right when we moved into the house. That helped me concentrate – I had no contact with anyone for a couple of months.

Frusciante: There are no such things as accidents.

Flea: Well, I would have much rather not broken my foot.

Frusciante: Some guitarists have the idea that there are technical prerequisites to being a great player. But all it takes is the ability to make music with complete abandon and total concentration.

Take Lou Reed’s playing with the Velvet Underground – to me that was twenty times better than that of most guys who practice twenty hours a day.

As long as you’re excited about what you’re playing, and as long as it comes from your heart, it’s going to be great.

Order the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ latest album, Unlimited Love, here.

Rod Brakes is a music journalist with an expertise in guitars. Having spent many years at the coalface as a guitar dealer and tech, Rod's more recent work as a writer covering artists, industry pros and gear includes contributions for leading publications and websites such as Guitarist, Total Guitar, Guitar World, Guitar Player and MusicRadar in addition to specialist music books, blogs and social media. He is also a lifelong musician.