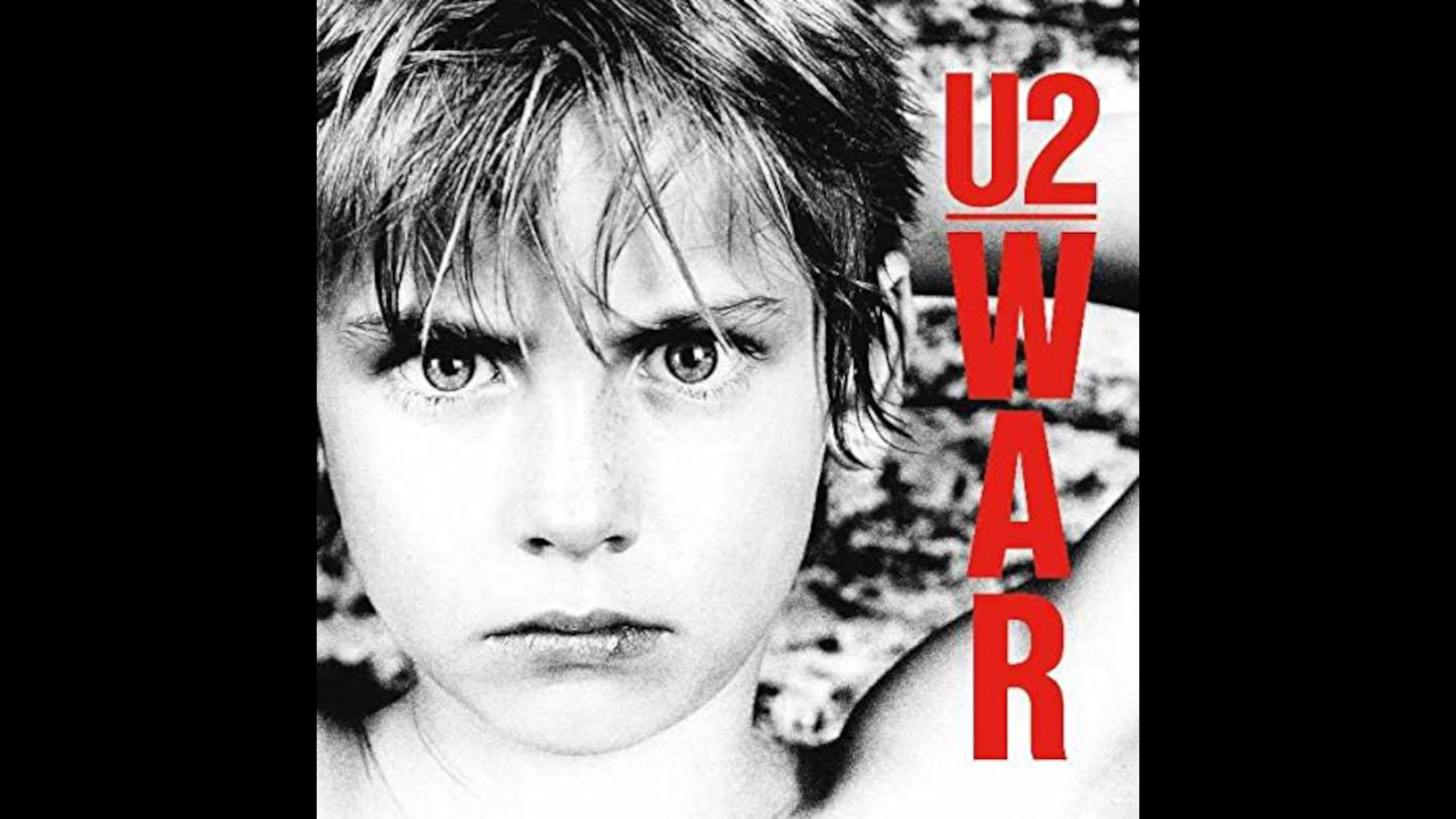

U2’s third album, War, is generally regarded as the band’s first truly great record. Although not officially a concept album per se – it doesn’t follow a dedicated storyline – the record has a prevailing theme centered around worldwide strife and the ravages of armed conflict, whether it was close to the band’s home base of Dublin or halfway across the globe. An impassioned and confrontational work, War was a critical and commercial triumph, and its rapid succession of smash singles – “New Year’s Day,” Sunday Bloody Sunday” and “Two Hearts Beat as One” – pushed it to Gold and Platinum status on both side of the Atlantic.

But in the months before U2 – singer-guitarist Bono, guitarist The Edge, bassist Adam Clayton and drummer Larry Mullen Jr. – began recording the album, there was little to indicate that they were on the verge of a breakthrough. There was doubt among them that they would make the record at all. “Going into the album, we’d gone through a bit of a crisis as a band because of our uncertainty about whether this was right for us,” The Edge says. “I mean, fundamentally, was it right for us to be in a band?”

Those concerns faded once the new songs took shape and demonstrated to them that their music could be a platform to address larger and weightier matters. “We came out of that after we’d written some songs that were really reassuring and confirmed that we could be involved in music and make some sort of positive difference,” The Edge says. “It was on War where we cut our teeth on activism and social justice issues.”

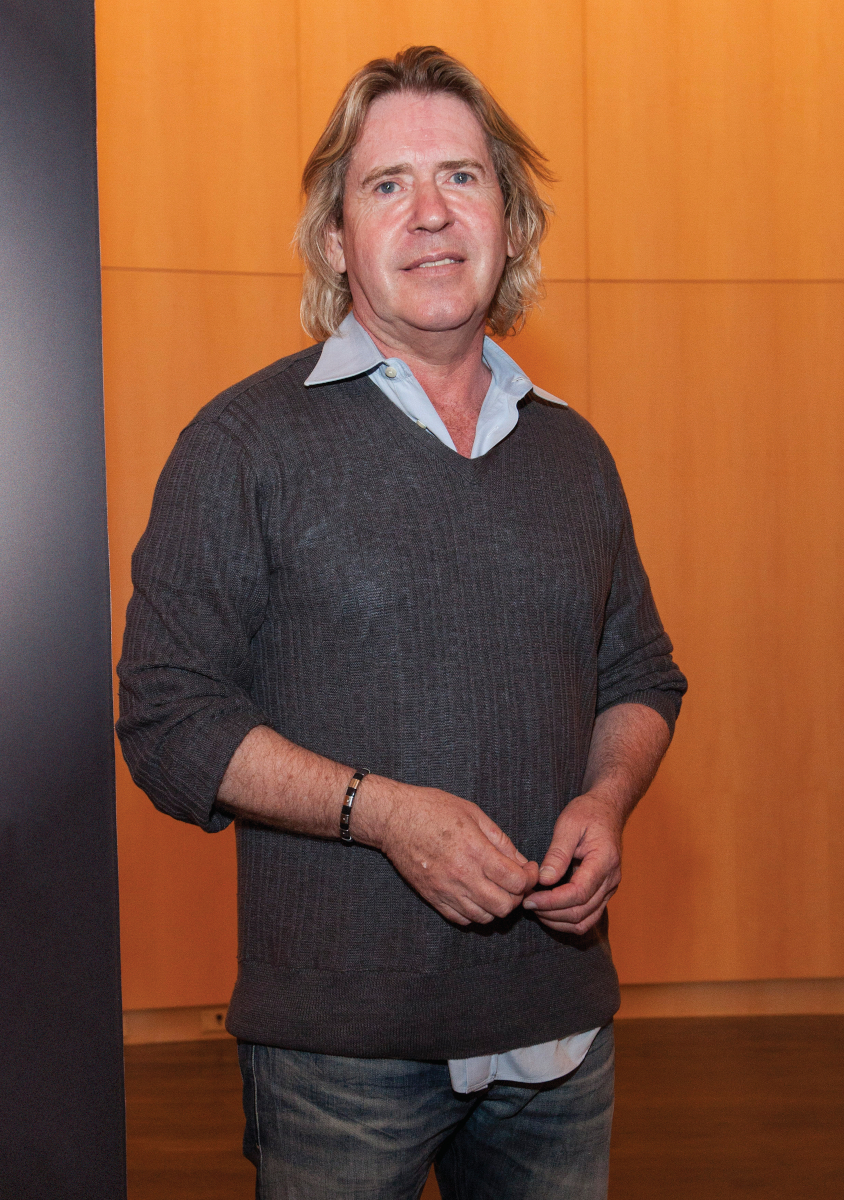

The band had worked with producer Steve Lillywhite on their 1980 debut album, Boy. At the time, Lillywhite was a rising star thanks to his collaborations with XTC, Siouxsie and the Banshees, and Peter Gabriel. He had established something of a golden rule of not working with the same band twice, but he came back a year later to produce U2’s follow-up, October.

Afterward, he figured the group would move on to work with somebody else. “Boy was seen as a big, successful first album, but October didn’t do as well as everybody hoped,” Lillywhite says. “I thought, Of course they’re going to want somebody else to produce the next record. Why wouldn’t they? And even though the second album underperformed, U2 were seen as a very hot band. Who wouldn’t want to produce them?”

In fact, the band had entertained a few other options. For a time, they considered working with multiple producers – possibly one per song – but that idea was soon discarded. Next, they recorded tracks with Sandy Pearlman (famous for his work with the Clash and Blue Öyster Cult) and Blondie keyboardist Jimmy Destri, after which the band decided to continue their search. A few other names were tossed around – Rhett Davies, Roy Thomas Baker and even Brian Eno, who would ultimately begin a long relationship with U2 starting with 1984’s The Unforgettable Fire – but nothing took.

Lillywhite was more than a little surprised when he got a call from Bono in early summer 1982, asking if he’d be interested in producing U2’s next album that fall. “At first, I thought, God, I’ve never done an album number three with anybody,” he says. “But then I thought, Sure, let’s do it. They always seemed to keep convincing me to come back. My sort of communistic morals changed slightly when I realized that it could be such a wonderful story if we could get it right with U2.”

Getting that story right wouldn’t be easy. Following their initial attempts at recording, the band had sketched out only a few new song ideas, which The Edge remembers as being “interesting, but nothing we were really excited about.” Lillywhite says this was par for the course. “They’ve had writer’s block their whole lives. It’s never come easily to them,” he says. “The first album was the result of three or four years of writing. They played those songs in clubs before they got signed. Even when we were recording, Bono hadn’t finished all the lyrics. I would have to tell him, ‘You’re repeating verses. You need to finish the song.’”

For much of the summer, the band was scattered. Bono and his longtime girlfriend, Ali, got married in late August and took off for a honeymoon in Jamaica. Says Lillywhite, “I’m not sure where Larry was – he was off doing his thing. And I went with Adam and U2’s manager, Paul McGuinness, to Italy, where we tried to cause as much mayhem as we could.” He laughs. “Some people spend their time in Italy going to art galleries. Adam and I spent our time getting fucked up. It was pretty crazy.”

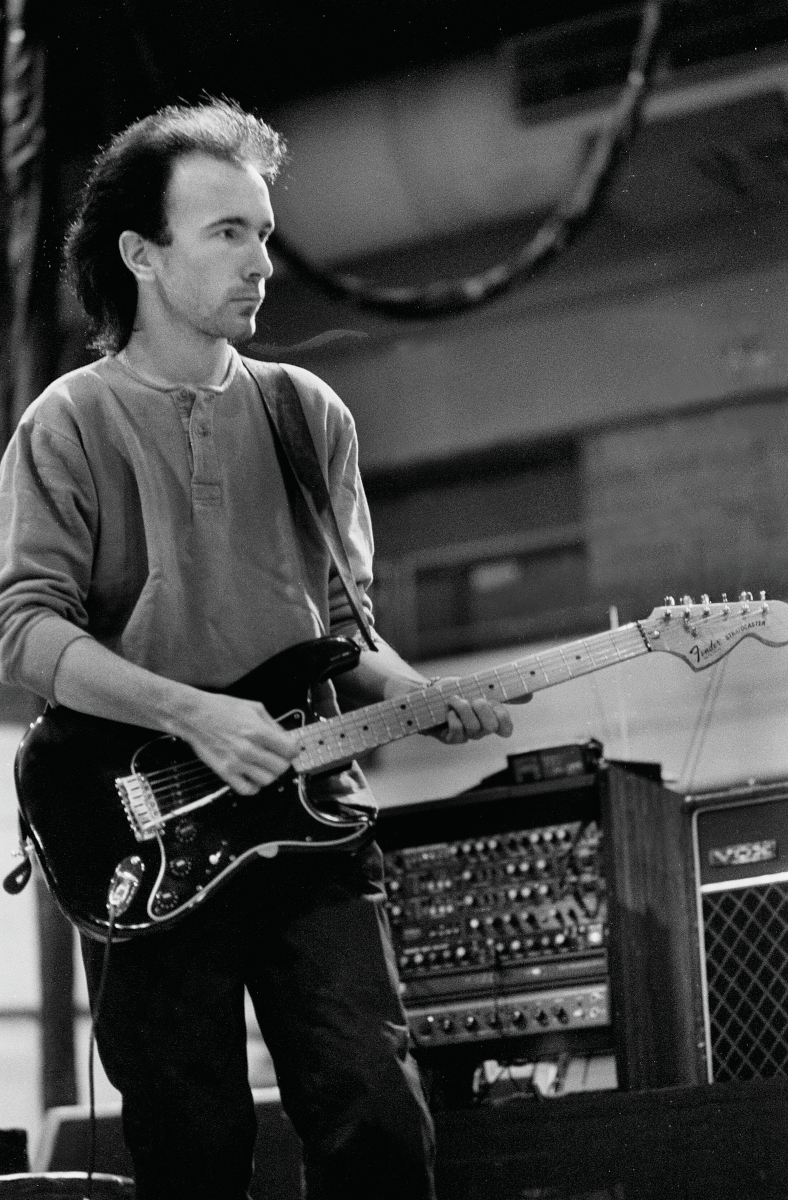

With recording time already booked for early September at Dublin’s Windmill Lane Studios, the brunt of the first real phase of songwriting – and taking control of what, if anything, the new album would become – fell on The Edge’s shoulders. “I had a conversation with Bono before he left, and I said, ‘I’ll see what I can come up with,’” he says. The guitarist sequestered himself in the band’s rehearsal space with “keyboards, drum machines and guitars of all shapes and sizes,” but little in the way of new material. “I had about two weeks to get some ideas going. We were kind of up against it. Luckily, ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ came about.”

The song’s rugged chord pattern appeared first, and it sounded promising. Once The Edge came up with the striking descending intro riff, he knew he was onto something. “It was instant,” he says. “As much as you would imagine there’s a limit to the permutations and combinations, since there’s only so many notes in the scale, when you hit on something that is essential, it’s kind of obvious. You can have differences of opinion about sound and lots of stuff, but songs are sort of empirical. Some songs are just better than others, and it’s not really a matter of opinion. The same is true of riffs. ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ was an absolutely pivotal song for us.”

‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ was definitely the catalyst. Musically and melodically, it was 90 percent finished, and it was fantastic. Suddenly, everybody was like, ‘Wow, we’ve got a great song here'

Steve Lillywhite

At the same time, Edge had become intrigued by a bassline that Adam had written. “It wasn’t really a song yet, but you could tell it was a great verse part,” The Edge says. “I took it and developed it into what eventually became ‘New Year’s Day.’” Other ideas took shape, notably the haunting anti-nuclear proliferation track “Seconds,” on which the guitarist would take his first turn singing lead. “To be fair, none of these were finished songs yet,” he stresses. “But it’s a funny thing: Sometimes it’s the essence of something to give you the clues. When the others came back, it was like, ‘I think we’ve got some new ideas. Check this out.’”

The guitarist played a cassette of his demos for the band and Lillywhite, and, all at once, spirits lifted. “Edge had been so stoic and diligent working on his own,” Lillywhite says. “Even then, he was like a scientist in terms of home recording, and the results spoke for themselves. ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ was definitely the catalyst. Musically and melodically, it was 90 percent finished, and it was fantastic. Suddenly, everybody was like, ‘Wow, we’ve got a great song here.’ Edge’s demo gave us a great template to work from. It sounded like the single right away, and my way of thinking is, if you’ve got the single, your work becomes so much easier. You pretty much have to fill in the rest of the album around it.”

The Edge was elated at the reaction. “It was a big relief,” he says. “Going into the sessions with Steve, we were like, Okay, now where can we take this?” Starting with The Unforgettable Fire, the bulk of which U2 recorded with Eno and Daniel Lanois at Ireland’s Slane Castle, the band would embark on projects at various remote studio locations. For War, however, they insisted on returning to Windmill Lane, where they had recorded Boy and October. “I think they prided themselves with making their records in Dublin at the time,” says Lillywhite, who remembers Windmill Lane as “a normal, go-to-work kind of studio. It had its limitations, because it was designed to record very quiet folk music.

“For my sonic palette, I needed big, loud, echoey atmospheres. The recording room never helped the sound. In fact, for Boy, I recorded the drums out in the hallway. I was always changing certain things about the studio to suit my sonic needs.” He laughs. “That said, I’m very proud that I was the first person to make a successful rock record in Ireland with an Irish band.”

Dispensing with pre-production, U2 and Lillywhite began the recording sessions with “Sunday Bloody Sunday.” The Edge’s demo provided a brilliant roadmap to work from. But from the start, it became clear to both band and producer that a musical reboot was in order. The new songs demanded it.

“The first album did well, but October was a little less focused,” Lillywhite says. “It seemed as if America had fallen in love with U2 the rock band, but they hadn’t fallen in love with U2 the ‘let’s sing songs about the Bible’ band.’ On October, Bono dug into his spiritual side. It wasn’t just the lyrics, though. The sound on October was slightly sleepy and confusing. It was soft-focus Doris Day. It’s a great album if you want to curl up and listen to music on a cold night.

“With War,” he continues, “the band definitely wanted to take things somewhere else, and that meant the sound had to reflect that. It had to be tougher and more in your face. It had to be hard-focus black and white.”

With 'War,' the band definitely wanted to take things somewhere else, and that meant the sound had to reflect that

Steve Lillywhite

U2’s studio sound would also be a more accurate representation of their powerful, take-no-prisoners stage show, but there, too, Lillywhite says some recalibration was in order. “I had seen them on the October tour, and to my ears it seemed as if the songs live were getting very brash and almost hard rock – not quite heavy metal, but definitely harsh,” he says. “I wasn’t sure that was the band’s strength. It had to harken back to the band’s roots, which were in punk rock. It had to be more Clash-like.”

Lillywhite recalls Bono encouraging the Edge to “stop sounding like The Edge. Sound like Mick Jones!” He laughs. “Now, Edge was always going to sound like Edge, but without Bono pushing him, he might have been ‘dreamy Edge,’ not ‘rocky Edge.’”

The guitarist was onboard with the notion of channeling the spirits of the band’s heroes, most certainly the Clash, but also the Patti Smith Group. But there was another band that loomed large in his mind: Television. “They were an immensely important band to us, particularly on the first album, Marquee Moon, because of its uniqueness and creativity,” he says. “We’d never heard the guitar played in that way before. They were making instruments that, to our ears, had such a clear identity and sounded completely new. That was a big throwdown for us.”

For The Edge, whose creative use of delay and echo effects had already made him one of the most distinctive young guitarists around, responding to that challenge meant “de-Edging” himself to some degree, rolling back the settings on his stomp boxes – or, in some cases, turning them off entirely. “On ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ and ‘New Year’s Day,’ I think we felt like it needed to be more direct and hard hitting,” he says. “We were consciously drying things up and making them more impactful and punchy.”

Lillywhite responded to the guitarist’s more naturalistic sound by leaving well enough alone. “That’s what a good producer does – you stay out of the way when something’s working,” he says. “If Edge got a certain sound from his amp, I had to trust his ears. I didn’t want him coming into the control room and hearing something totally different. Whenever he rolled the delay and echo off his sound, I kept it that way. I never added those effects back.”

At the time, The Edge’s guitar collection was still limited to a few models. There was his ever-present 1976 Gibson Explorer (which he bought for $248.40 in 1978 in New York City while vacationing with his family), along with a ‘70s Fender Stratocaster and a 1975 Gibson Les Paul Custom. During a tour stop in New Orleans, he’d purchased a lap steel that he employed on the song “Surrender.” Says Lillywhite, “We spent days trying to get it right. It sounded great, but I think Edge could have done it on a bottleneck and it would have sounded just as good.”

Edge and that Vox amp were connected. You could never separate the two of them, and why would you even try?

Steve Lillywhite

On certain cuts, he occasionally played through a Fender Twin, but his go-to amp was the same 1964 Vox AC30TB that he’d used since the beginning days of the band. “Edge and that Vox amp were connected,” Lillywhite says. “You could never separate the two of them, and why would you even try?”

As recording continued, riffs and chord patterns grew into complete song structures. The band had already worked in this manner on October, and on War they refined their ability to write on the spot. “It wasn’t so much about jamming – they weren’t really a jamming band,” Lillywhite says. “It was more about them playing parts until we had something.”

New to the studio process was the use of a click track, which benefitted the band’s cut-and-paste method of recording. “Up to this point, their recordings were like surfing – you go up [in tempo] and you go down,” Lillywhite says. “Because a lot of the songs on War were patchwork quilts, it was important for us to have a solid foundation of timekeeping. Suddenly the bass could [get recorded] very easily because all Adam had to do was lock into it. Edge took to the click quickly. I remember spending a day with Larry to get him used to it. I told him, ‘If you hear the click while you’re playing, it means you’re out of time. He got the hang of it, and before long he loved playing to the click.”

One area in which Lillywhite didn’t involve himself was Bono’s lyrics. “I know there are producers who like to pore over every word, but that was never my thing, really,” he says. “There were band discussions during which they’d talk about their ideas and issues, but they didn’t lay out any kind of political or thematic agenda for me, nor did I think to offer an opinion. I knew what they put themselves through, and I knew Bono would have to live with his lyrics for the rest of his life, whereas my connection to the record wasn’t so personal. My main focus was on making sure the lyrics were done so we could record. My attitude was, Let’s just do this!”

Not all of the songs on War carried political themes: The crashing rocker “Red Light,” highlighted by The Edge’s slashing chords and thorny riffing, concerned prostitution. On “Two Hearts Beat as One,” the band’s first foray into dance music (a genre they would explore in myriad ways in the ’90s), they focused on desperate romantic yearning and hit an emotional bull’s-eye.

Sonically, “Two Hearts Beat as One” deviated from the limited guitar effects rule, as it saw The Edge utilizing a flanger to color the sound of his stinging rhythm playing. In stark contrast to his usual method of sonic architecture – working assiduously with amps and effects to arrive at a dedicated combination – the guitarist remembers his approach to the song as one of divine inspiration and spontaneity.

It was such an important album for us. And Steve Lillywhite was a great ally and a great additional member of the creative team for the recordings

The Edge

“Bono and myself and Dunx [engineer Duncan Stewart] were in this little room in my house, just trying different ideas out,” he says. “I’m quite happy to spend time experimenting, but Bono likes momentum. That’s what he feeds off. If you get a lot of momentum going, that’s where he really shines creatively. Oftentimes, when we’re working together, we’ll be moving at lightning speed to get something happening. In that case, we were really quick. And then this sound arrived. It was like, ‘Okay – let’s go!’ I appreciate that. Sometimes I find that draws things out of me I wouldn’t have thought of otherwise. Being put on the spot can be a really good thing.”

The band brought in a smattering of guests – American trumpeter Kenny Fradley duked it out with The Edge in the solo section of “Red Light,” while Irish violinist Steve Wickham contributed memorably to “Sunday Bloody Sunday” and the atmospheric ballad “Drowning Man.” Three cuts – “Surrender,” “Red Light” and “Like a Song… ” – feature backing vocals by Kid Creole’s Coconuts. “The guys were getting into a lot of music from New York, and at the time Kid Creole was very big in the U.K.,” Lillywhite says. “When the Coconuts came to Dublin, it was like, ‘Come down and hang out. We’ve got a couple of songs that could use that New York club feel.’”

In order to meet the deadline for record manufacturing plants (which took between two to three months to turn product around), the band squeezed the last minute out of their studio time. “We didn’t even have the opportunity to sit back and listen to the finished album,” Lillywhite says. “Right up to the end, Bono was doing the final vocal, and Edge was doing the last guitar overdub. They finished and the record went to production. Nobody could sit back and say, ‘Aren’t we fucking great?’”

That assessment came from critics and fans upon War’s release in February 1983. In a lengthy rave review, Rolling Stone’s J.D. Considine wrote “the songs here stand up against anything on the Clash’s London Calling in terms of sheer impact.” And in Dublin’s own Hot Press, writer Liam Mackey hailed the album as offering “watertight evidence of the band’s standing as a genuinely original force in contemporary music.”

Thanks to heavy play on MTV for “New Year’s Day” and “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” War hit number 12 on the Billboard Hot 200, giving U2 their first Gold record in the U.S. In the U.K. it went to number one, knocking Michael Jackson’s Thriller – the best-selling album ever – from the top spot.

Forty years after rushing the production master off for pressing, Lillywhite sat down recently and gave the album a dedicated listen. “It’s rare that I do that kind of thing,” he says, “but I can tell you I was very pleased by what I heard. It’s really something special. ‘New Year’s Day’ is absolute perfection. I’m so honored to have been involved with the album.”

The Edge returns the compliment. “It was such an important album for us,” he says. “And Steve Lillywhite was a great ally and a great additional member of the creative team for the recordings. He really brought a lot to the project.”

Order U2's War here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

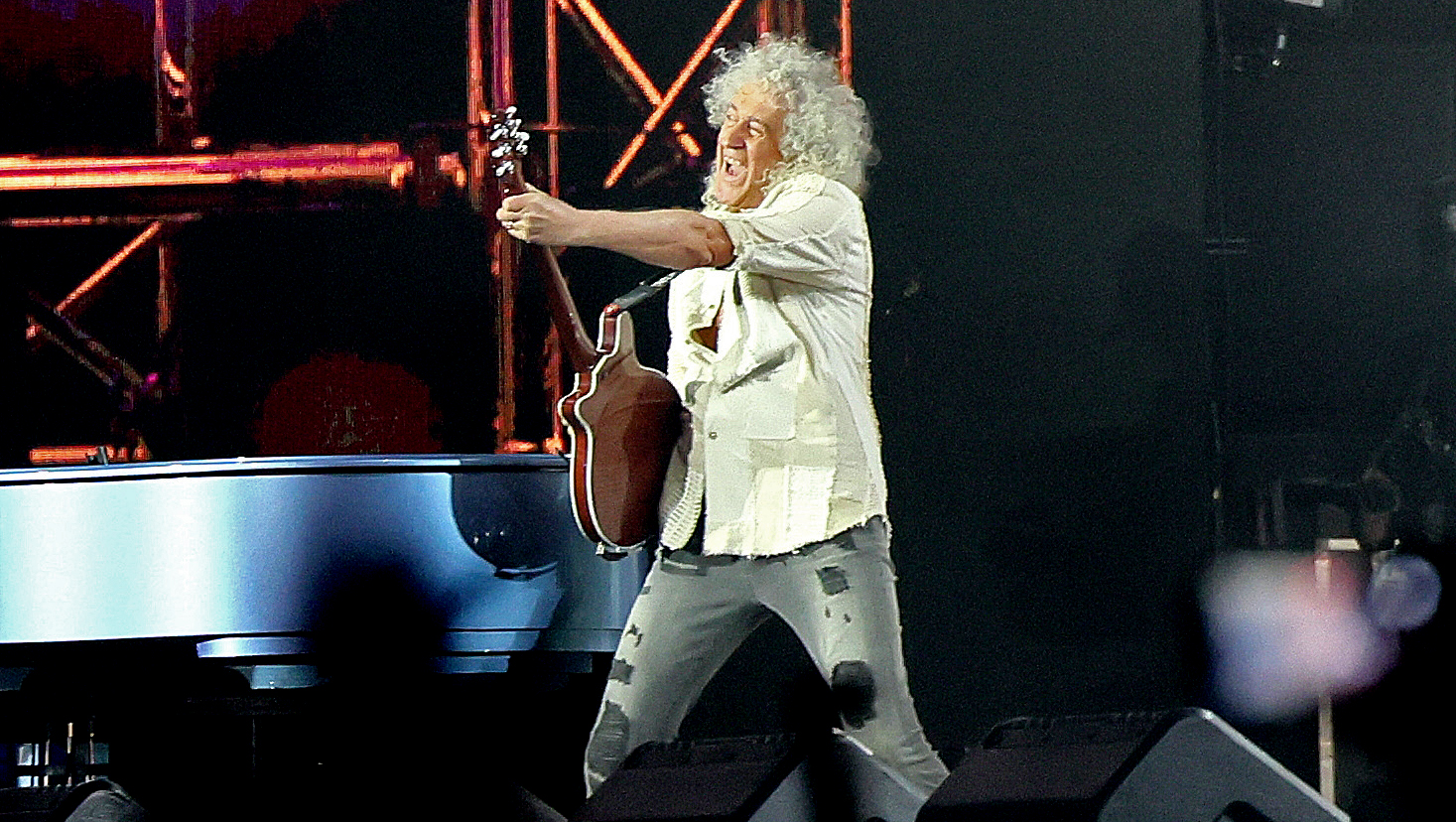

"This 'Bohemian Rhapsody' will be hard to beat in the years to come! I'm awestruck.” Brian May makes a surprise appearance at Coachella to perform Queen's hit with Benson Boone

“We’re Liverpool boys, and they say Liverpool is the capital of Ireland.” Paul McCartney explains how the Beatles introduced harmonized guitar leads to rock and roll with one remarkable song