“Rehearsal rooms are expensive in Los Angeles. So I decided to buy a boat. It’s way cheaper.” How one Grammy-winning guitarist, three Gibson ES-295s and a tiny ship became a formula for musical success

Garcia Diego's unique approach begins with his music, an unusual and energetic mix of traditional Spanish acoustic styles and rock

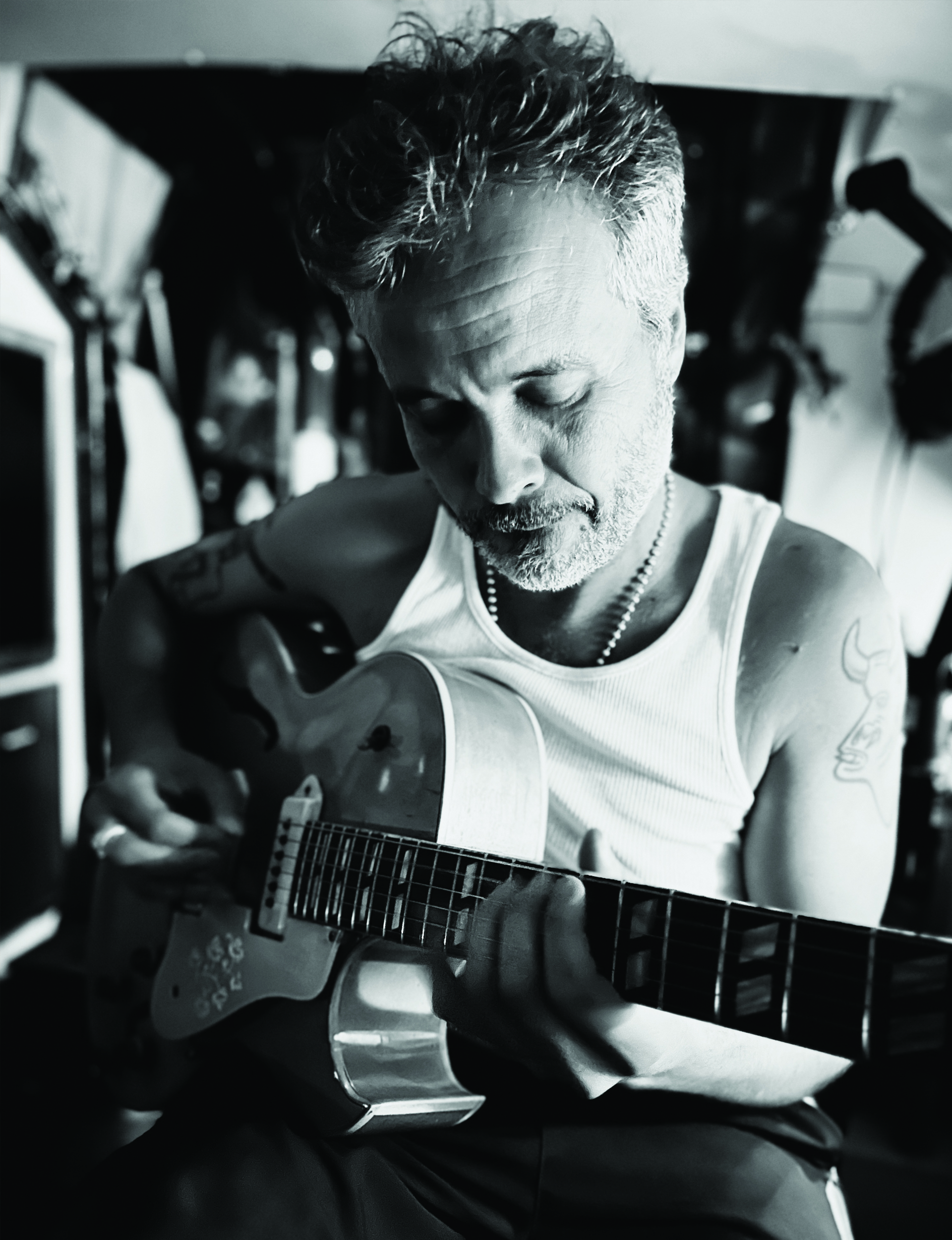

![Diego Garcia, a.k.a. Twanguero, plays his 1955 ES-295 on Panamerica. “I purchased [the boat] because rehearsal rooms are so expensive,” he says.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cfFmbvV4c4GjJAKeGQvyU5.jpg)

If you want to find Diego Garcia these days, head to Marina Del Rey in California and look for the boat studio where he makes his home — and whose name, Panamerica, is also the title of the award-winning Spanish-born guitarist’s latest album under his performing moniker, Twanguero.

“It’s like a small apartment for me,” Garcia, 48, explains. “I purchased it because rehearsal rooms are so expensive here in Los Angeles; it’s almost like renting an apartment on top of whatever you’re renting to live in. So I decided to buy a boat. It’s way cheaper.

“I know Bob Dylan used to have a boat here, like two slips away. So if it was good enough for him...”

Although it’s no competition for the larger yachts that populate the marina, the Panamerica is a kind of all-things proposition for Garcia. “We can have a studio here, we can rehearse the band here,” he says. “It’s inspiring when you watch the sunset over the Pacific Ocean when you’re playing a guitar and smoking a joint or something.” Equally inspiring, he adds, “There’s a small community of musicians here in Mariana del Rey: some people from Argentina, some people from the Congo... a lot of places. We have friends, we have jams. People here in the marina know us. They like when we’re playing. When we’re playing some cumbia or something, all the Mexicans that come to work on the boats love that music. So it’s good.”

Indeed, it takes a village — in his case, a global village — to make Twanguero’s music. His output over seven albums has been shaped by his travels, logging time in Buenos Aires, Mexico City, New York and, for the past eight years, California. That makes all of his music, including Panamerica, an aural travelog from Spain to Latin America to the Mississippi Delta and Sun Records in Memphis. The 10-track, largely instrumental album mixes North American electric guitar and rock and roll with Latin American classical guitar–based styles, including bolero, cumbia, Tejano, ranchera and rhumba, as well as Hawaiian, surf and country. It all adds up to a throwback vibe that Garcia calls “new nostalgia,” as if the listener is flipping between radio stations in some multi-cultural milieu of decades past.

While his approach is unorthodox, it’s never irreverent. Garcia has a serious and genuine love for quite possibly every kind of music. And he loves expressing it in his own voice, mostly with a Gibson ES-295 slung over his shoulder and a cadre of musical kindred free spirits around him.

“I don’t see myself in any particular style,” Garcia explains. “I respect them all. I’m not a purist. Maybe some purists hate me. Like flamenco players: ‘What’s this guy doing with an electric guitar?!’ The purists are maybe upset with me, yeah. But I explore different styles with no fear. I’m a rocker, but I like to apply that idea to those ancient musical philosophies and respect the music. ‘Respect for the music’ is our guide.”

The second oldest of four children, including two sisters and a brother, Garcia was raised in Valencia, with music in his DNA through his paternal grandfather. His own parents “had to work a lot” to support the household, but from about the age of eight Garcia and his brother (now a teacher in France) were able to pursue their musical studies on weekends at a public conservatory, working with a teacher who had been a student of the legendary Andrés Segovia. The heritage, he says, taught him “discipline and a lot of respect.” For summer vacation the master would give Garcia a handwritten letter wishing him a good summer and reminding him to practice. “And he always added a couple of transcriptions to study: ‘I will ask you in September to play these for me,’” Garcia recalls.

“That was the relationship we had with the instrument. We come from that tradition. We took it very seriously.”

“I saw that Stratocaster Hank Marvin had. I’d say, ‘Wow, I want to play that!’ I was in love with Jeff Beck and Chet Atkins and Link Wray."

— Diego Garcia

Bolero and rhumba were one thing; rock and roll was another — and one that was even more seductive for the aspiring player. “I remember my father had the Shadows on vinyl,” Garcia says. “I saw that Stratocaster Hank Marvin had. I’d say, ‘Wow, I want to play that!’ I was in love with Jeff Beck and Chet Atkins and Link Wray — all those sounds. I was more into Eric Clapton when I was 13, 14. I wanted to be Mark Knopfler. This was after ’75, when Franco died. Spain opened up a lot. We heard a lot of British music, and the artists came to perform.”

While the classical teachers generally frowned on electric guitars and rock and roll, Garcia knew it was his future. “First of all, classical guitar you have to play in a chair,” he notes. “I wanted to play standing up — and get girls, probably. That’s why I switched to electric.”

Soon after, his parents bought him his first electric guitar, an all-black Samick Strat knock-off from Japan. While Garcia does own an Olympic White 1964 Stratocaster, he’s particularly attached to the ES-295, with 1956, 1957 and an early ’90s model in his arsenal. “It’s the rockabilly guitar,” Garcia notes. “I remember seeing it on an early Elvis Presley album; Scotty Moore had a gold-top that was just beautiful. It’s a jazz guitar, but with P90s it’s more rockabilly.”

It also fits Garcia’s ‘Twanguero’ nickname, an onomatopoeia of a string’s vibration. “For me, Twanguero is a project,” he explains. “Twanguero is a vision of seeing the world and the music through the guitar, not competing at all but learning from here and there, finding my personal path and sharing it with the world. That would be the life’s goal of any musician’s career.”

There have been many paths, geographically and musically, that Garcia has followed over the years. Along the way he won a Latin Grammy Award for producing Rodolfo Mederos & Cuarteto Q-Arte’s 2002 album, Tango Sacro. He also spent time in the Costa Rican rainforest composing songs for his last album, Carreteras Secundarias Vol. 2, released in 2022. “My career has been shaped by all this traveling,” he says. “Because I search through the guitar. I never have anything planned, but I’m always influenced by where I am. Jeff Beck was a maestro of the guitar, but I’m an explorer — forever.”

"My career has been shaped by all this traveling. Because I search through the guitar."

— Diego Garcia

Traveling became more complicated when the pandemic hit in 2020. Isolated on his boat for the better part of a year and a half, Garcia missed playing with others, but he stockpiled ideas. “We tried to do remote recording, emailing audio files, but I wasn’t happy,” he says. “But I had a lot of time and inspiration, so I could design — abstractly speaking — what I wanted and think about the musicians I would want to play on them.” As soon as he was able, Garcia rented a studio in Culver City, close to Marina del Rey, and began bringing his compatriots there to hang out as much as to record.

“I rented it and lived there for a year, so I didn’t have to pay for hours and could bring my guys there,” he recalls. “It was a celebration of friendship. I love to cook, so we’d have the barbecue going and we’d play and explore.”

The collective was crucial to the album’s sound as well. “You just pick the right people to look for a sound,” Garcia says. “In Los Angeles it’s very easy to find good people — like a good percussion player who understands Elvis and the salsa. So it’s all about hanging with the right guys, the right people. And then I write for my guys.”

But the key, he adds, is creating songs that might be outside their wheelhouse — having former Black Crowes drummer Brian Griffin play a cumbia, for instance, or laying Bob Bernstein’s pedal steel into a bolero. Garcia also takes on the traditional “La Bikina” on Panamerica, moving it from a six-eight into a straight four-four to create “a more Caribbean, dreamy situation.”

“I think the audience needs some fantasy too,” Garcia expounds. “The composer needs to create a picture that he can pass along in the song. Like my song ‘La Bikina’ — I have a cheap boat, but there are a lot of big yachts passing through in the summer with women on their decks in bikinis. That’s ‘La Bikina.’ It puts a picture in your mind. That’s the fun thing of art, no? Giving yourself the freedom to imagine creative things that can make people happy. That’s the cinematic way of playing.”

"You improve your skills in so many areas, not just music. The mission is going higher, bettering what you love. That’s the point of the thing.”

— Diego Garcia

Garcia says he did a different style of playing on Panamerica, too. “Now I play with my fingers, the way I was playing Spanish guitar — with nails. I play that way on the electric guitar,” he explains. “But, of course, steel strings are different than nylon strings, so I try to adapt the attack. Instead of having a pick, which would be more the American style, I’ve been working the last two years to get that sound from my hands.”

Panamerica’s release puts Garcia and company back on the road, hoping to build his U.S. footprint up to the level of his strongest markets in Europe and Latin America. And while the album is job one now, Garcia’s own wanderlust has him thinking about what — and maybe where — comes next.

“Moving here and there gives you the freshness of starting again,” he says. “Maybe I’ll stay longer in Los Angeles, but moving and starting over, making contact, trying to socialize with a community — that’s something I’ve been doing, and it’s a gas. You improve your skills in so many areas, not just music. That’s what nurtures the spirit, or the soul. The mission is going higher, bettering what you love. That’s the point of the thing.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened