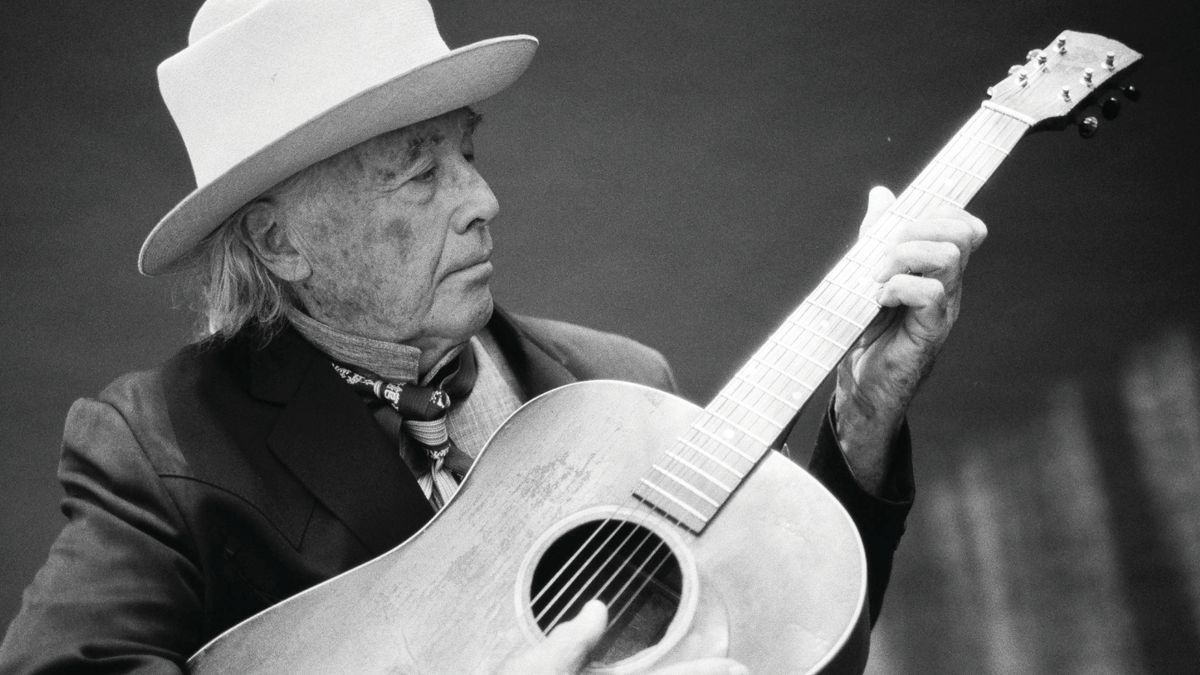

“There Was Something Special About ‘Get On Board’”: Ry Cooder Talks New Collaborative Album

The guitarist reunites with Taj Mahal for ‘Get On Board: The Songs of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.’

Ry Cooder and Taj Mahal started out together with the short-lived Rising Sons before parting ways and going on to become two of the most important individual figures in American music.

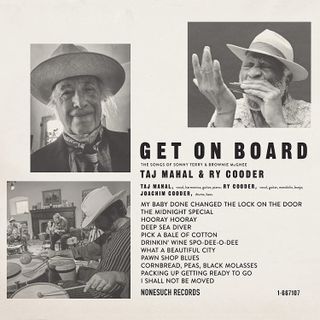

Now they’ve come full circle to pay tribute to two of their original heroes with the album Get On Board: The Songs of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee (Nonsuch).

To be honest, we had a sense that a project between these heavyweights was in the offing. Last year, as Mahal turned 80, he graced our pages with a historic two-part interview.

[Click here for part one of Taj Mahal's interview.]

[Click here for part two of Taj Mahal's interview.]

While he told us at the time that he was in contact with Cooder, it seemed futile to speculate on what that might mean while the pandemic was in full swing.

This time, we spoke with Cooder on the date of his 75th trip around the sun – March 15 – and he enlightened us about the project and the fascinating instruments he brought to the almost entirely acoustic affair.

Once again, it will take two parts to deliver all the goods that he gave to us.

[Click here for part two of Ry Cooder's interview.]

For the uninitiated, suffice it to say that GP long ago enshrined Cooder in the Gallery of Greats for his astounding array of solo albums, soundtrack work (including 1986’s Crossroads), sideman credits with everyone from the Rolling Stones to Little Feat, and of course, his expedition to Cuba that yielded the musical and cultural renaissance that was the Buena Vista Social Club.

If they ever create a Mount Rushmore of influential guitarists on Americana Mountain, it would surely be graced with Cooder’s face.

Get On Board: The Songs of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee finds him continuing his musical journey in a way that will appeal to fans of an authentic down-home aesthetic. The album has a back-porch feel, with a live parlor room sound.

Cooder wields an array of vintage acoustic guitars plus mandolin, banjo and a cameo by his most infamous electric guitar.

Mahal mostly sings and plays harp.

Their reunion is a long time coming. After forming Rising Sons in 1965 (the name referenced Terry & McGhee’s song “Rising Sun” from the 1952 Folkways album Get On Board), Cooder and Mahal were signed to Columbia, recorded an album that was shelved, and quickly disbanded.

The record was officially released as Rising Sons in 1992. While they haven’t teamed up for another collaborative studio effort until now, Cooder contributed guitar to Mahal’s 1968 eponymous solo debut.

On Get On Board: The Songs of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, they do great justice shedding considerable light on one of the most influential and enduring duos in the history of the blues.

The collaboration of harmonica player and vocalist Terry with guitarist McGhee lasted more than three decades, from the early ’40s to the mid ’70s, when they cut gems such as “Midnight Special,” “Drinkin’ Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee” and “I Shall Not Be Moved.”

Accompanied by his son Joachim Cooder on drums and bass, Cooder and Mahal revitalize the material with purposeful vigor as they approach the twilight of their careers.

Of the million things you two might endeavor together after more than a half a century apart, how did you settle on a tribute to Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee?

Well, mostly because I knew we could pull it off. It’s way of having a context and a repertoire that’s coherent.

After all the songs they did throughout so many years on so many albums, there was something special about Get On Board. It was the first album of theirs that I knew about as a kid, and it simply came across as good music.

It’s way of having a context and a repertoire that’s coherent

Ry Cooder

Of course, Brownie was shooting for a white audience at that point. They weren’t going to be playing what Black folks were listening to as popular music anymore. It was pre-war after all, that whole Piedmont style.

Piedmont blues is commonly described as having an alternating thumb with a melody line over the top, but that’s true for many fingerpicking styles. What’s your take on Piedmont specifically?

Well, you have something there. What people are referring to has something to do with the archeology. I guess Black folks came up from the Caribbean and settled in that area [Piedmont stretches from New Jersey in the north to central Alabama in the south].

They had a certain rhythm, swing and phrasing that’s antique now, I mean it’s ancient.

What was it about the guitar playing on Get On Board that resonated with your young soul?

I was about 11 or 12 when I first heard Get On Board. I had no idea who Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee were. You don’t know very much when you’re from Santa Monica at that age, but I knew that 10-inch Folkways LPs were always interesting, and you were going to learn something.

There was no folk music to be found anywhere else in Los Angeles except for this one particular record store. Two sisters ran it, and they’d let you play a record to see if you liked it.

It’s fun, the guitar is great and the harmonica is incredible. What they were doing was very stimulating

Ry Cooder

I’d take the bus to this store and poke around. I played Get On Board and said, “Oh wow, this is fantastic.” It’s fun, the guitar is great and the harmonica is incredible. What they were doing was very stimulating.

You know, Brownie stepped into Fuller’s shoes when Fuller died. [Blind Boy Fuller was Brownie McGhee’s mentor. He set the guitar-and-harp mold with Sonny Terry that McGhee stepped into and furthered.]

Can you describe some technical stuff about what Fuller handed down to McGhee and in turn, your own playing?

I don’t know any technical stuff, but even at that age I had been playing guitar somewhat, and I knew what I was hearing.

The thumb is the rhythmic downbeat, so the thumb goes down, and then the fingers come up, mostly the first finger and sometimes the second finger

Ry Cooder

The thumb and the fingers are doing separate jobs. The thumb is the rhythmic downbeat, so the thumb goes down, and then the fingers come up, mostly the first finger and sometimes the second finger.

It’s somewhat intricate and requires good coordination to learn, of course. I’m not saying that I could do it like Brownie when I was 12 years old by any means, but I understood his system.

In the videos you’re clearly using a thumb pick, which he did as well, correct?

Yes. It was just the two of them, so Brownie’s guitar had big job to do. It’s the rhythm, and the rhythm has got to be heard. Players needed finger picks to get enough volume for the acoustic guitar to be a strong rhythm instrument.

Some played National guitars with steel bodies. What I knew Brownie to play was a D-18 Martin.

Prior to that he played a J-45 Gibson, probably one of those banner guitars [referring to World War II era flattops with the slogan “Only a Gibson is Good Enough” in a golden banner on the headstock].

That’s not nearly loud enough if you’re on a microphone in a joint, a little club with a poor sound system. But Brownie was a strong man with strong hands, and he really bore down on that D-18. Let me tell you, he played it for dear life. So you had to have strength, but you had to have finger picks.

Players needed finger picks to get enough volume for the acoustic guitar to be a strong rhythm instrument

Ry Cooder

I don’t like finger picks at all, but if you’re going to play that way as I did on this record – use ’em. You need the thumb pick, but for room recording finger picks can be optional.

I tried finger picks for some of the tunes to see if I could get the right thing going, but for others I didn’t like using them because it’s clumsy. I can’t keep them on. They fell off my fingers a couple times.

But Brownie never had any trouble. He was a good player, and both the thumb pick and the finger picks seemed essential.

What type?

Well, back then we had National picks, but you can’t get them anymore. The ones I have now are Mike Seeger’s that came with a banjo of his that I bought after he died. The picks they make now are terrible. The metal is wrong. But those old National picks are good because they’re softer and make a prettier sound.

The difference is that now we record with earphones, so we don’t need to play so hard

Ry Cooder

If you’re going to do Brownie, then sometimes you’ve got to use them. The difference is that now we record with earphones, so we don’t need to play so hard. Turn up the earphones, you don’t have to force it as much, and your rhythm is better.

I’m sure they didn’t use earphones when they recorded. Of course, why would they?

How did you capture such a great live room sound?

Taj and I each had a couple of microphones placed close together in front of us with my son Joachim playing drums in his living room. It’s a small space, but for this it was the perfect size.

The ceiling height works well because you don’t get reflection off of it. The room wasn’t designed as a studio, obviously, but it’s excellent for acoustic instruments.

What’s going on in “Packing Up and Getting Ready to Go,” which sounds particularly roomy with a wild string tone?

Mahogany gives the D-18 a nice bright, snappy sound

Ry Cooder

That’s a crazy enormous gut-string banjo. Before Taj even arrived when we were setting up I started playing the thing through the mics and earphones to see if it was going to be useful.

Then Joachim came, sat down and started playing his drums. It was a cool groove, something different, so we edited it down and used it for that song.

You mentioned McGhee playing a D-18 and you appear to be playing a vintage Martin D-18 on some songs in the videos as well, including “I Shall Not Be Moved.” What makes mahogany the right wood for this sound?

Mahogany gives the D-18 a nice bright, snappy sound. So it helps you do that, it helps you be snappy.

The D-28 [rosewood with a spruce top] is mellower or bigger, but not as snappy and therefore not as useful for this kind of music. I’ve got one and I tried it, but it didn’t come across as well on the mic.

The D-18 that you see is a 1946, so it’s still a good year. The sound is very dry, and it’s been played to death, so it’s nice and responsive. The neck is a little clumsy like some of them were in the wartime, but it’s a really good guitar for playing blues with picks.

If you don’t like fingerpicks, then you’d want a flatpick. But as soon as I put the picks on, the instrument seemed to agree: “Ah, now we’re ready for business here.”

Click here to order your copy of Get On Board: The Songs of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jimmy Leslie has been Frets editor since 2016. See many Guitar Player- and Frets-related videos on his YouTube channel, and learn about his acoustic/electric rock group at spirithustler.com.

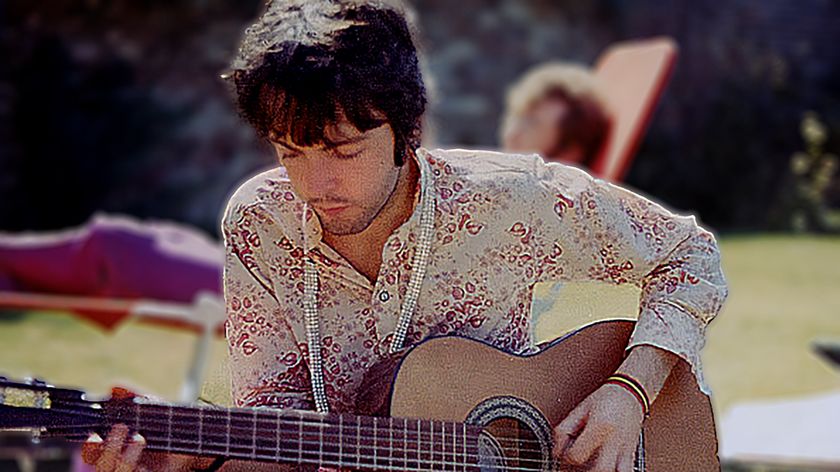

"We thought his music was very similar to ours, and we latched on to him amazingly quickly.” Paul McCartney explained how a youthful error led him to write one of his greatest guitar tracks for the Beatles

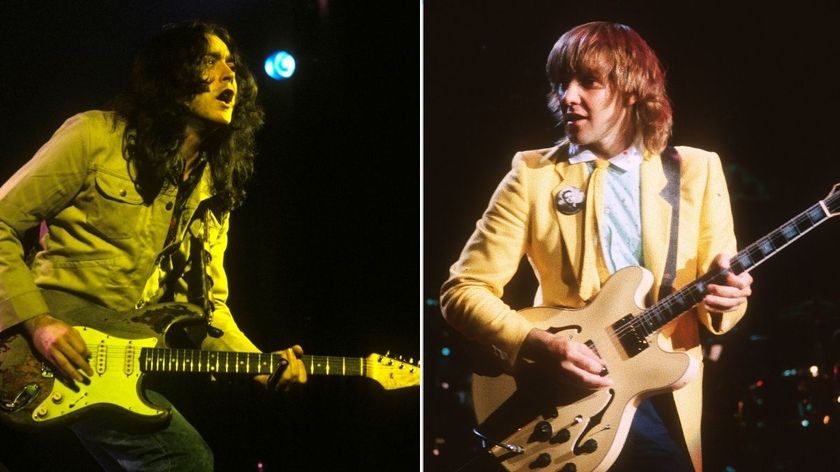

"I thought, Wow, what an effective thing to do! And I learned it directly from him.” Alex Lifeson reveals the technique he stole from Rory Gallagher during their time together on the road

Most Popular