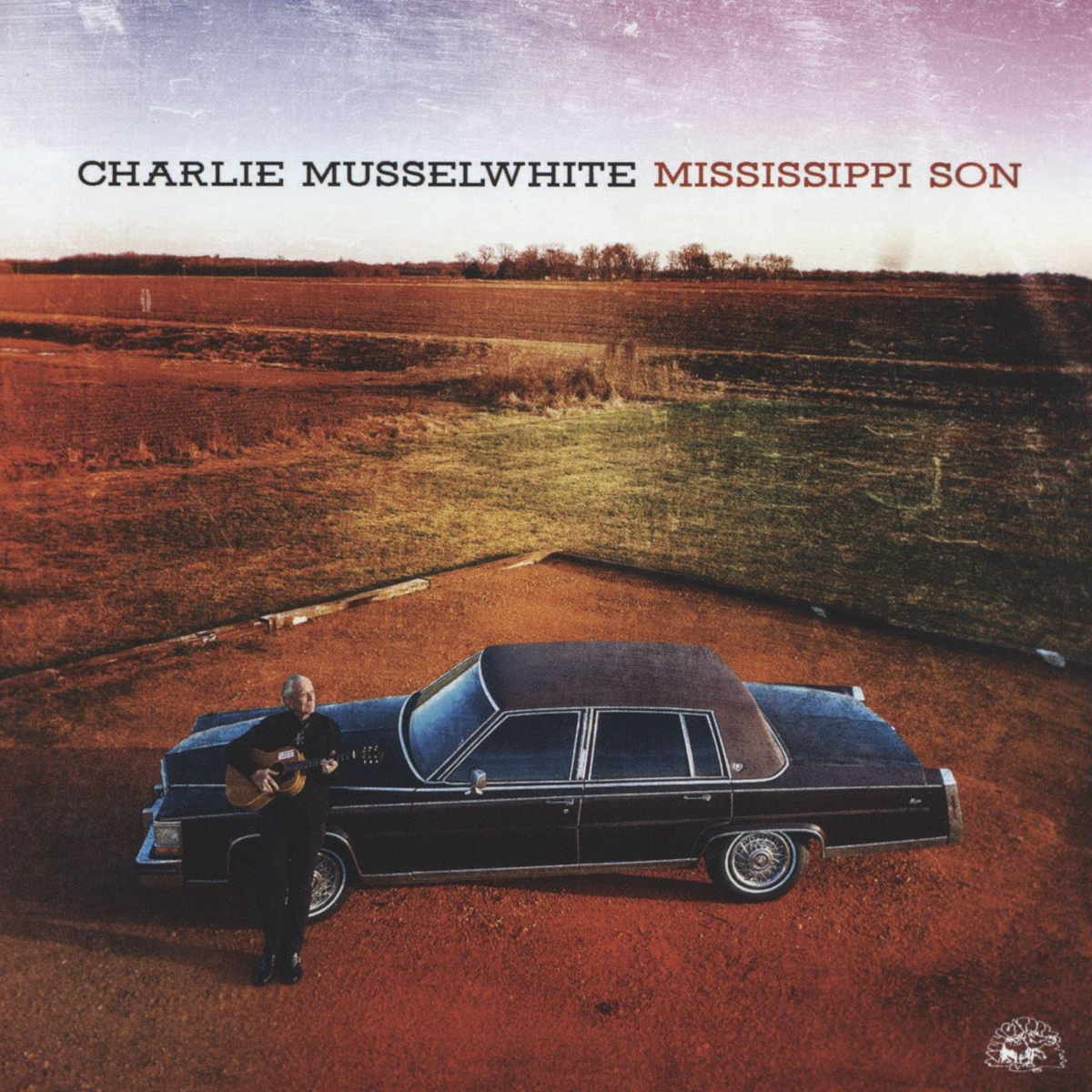

“There Was More to It Than Just Music”: Charlie Musselwhite Talks Blues

The revered harp player finds his way back to the guitar on new album, ‘Mississippi Son’

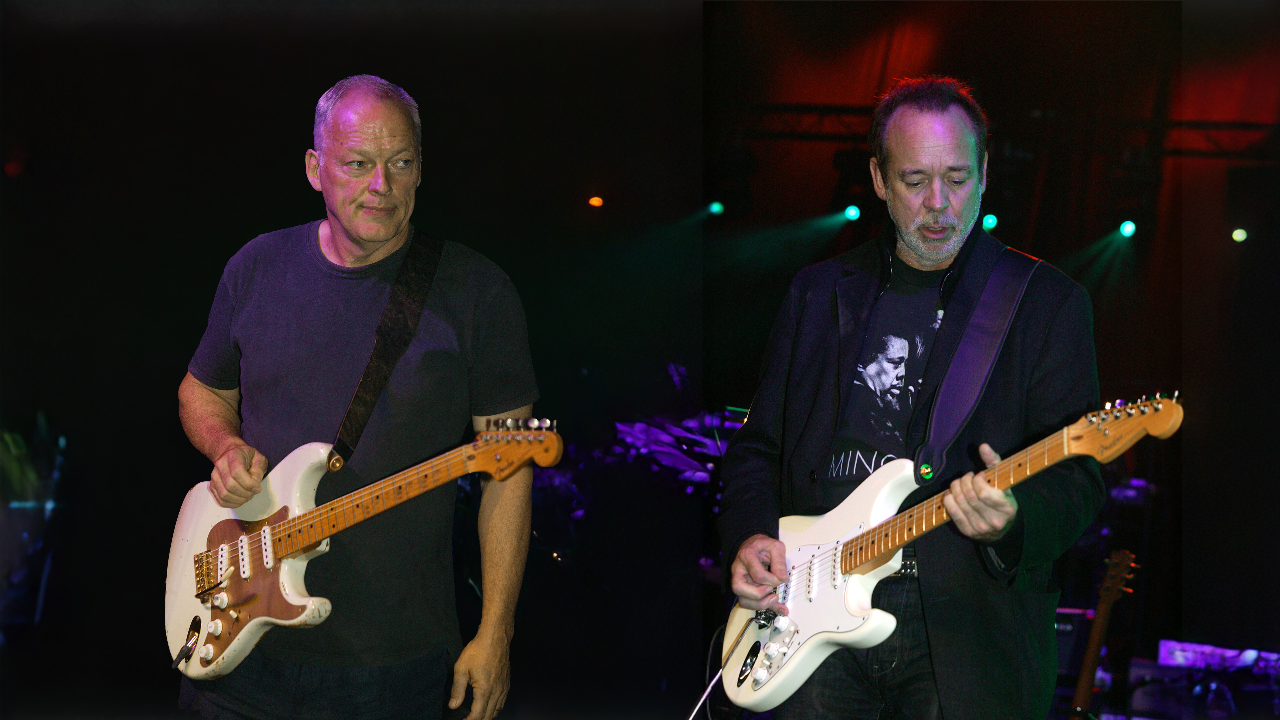

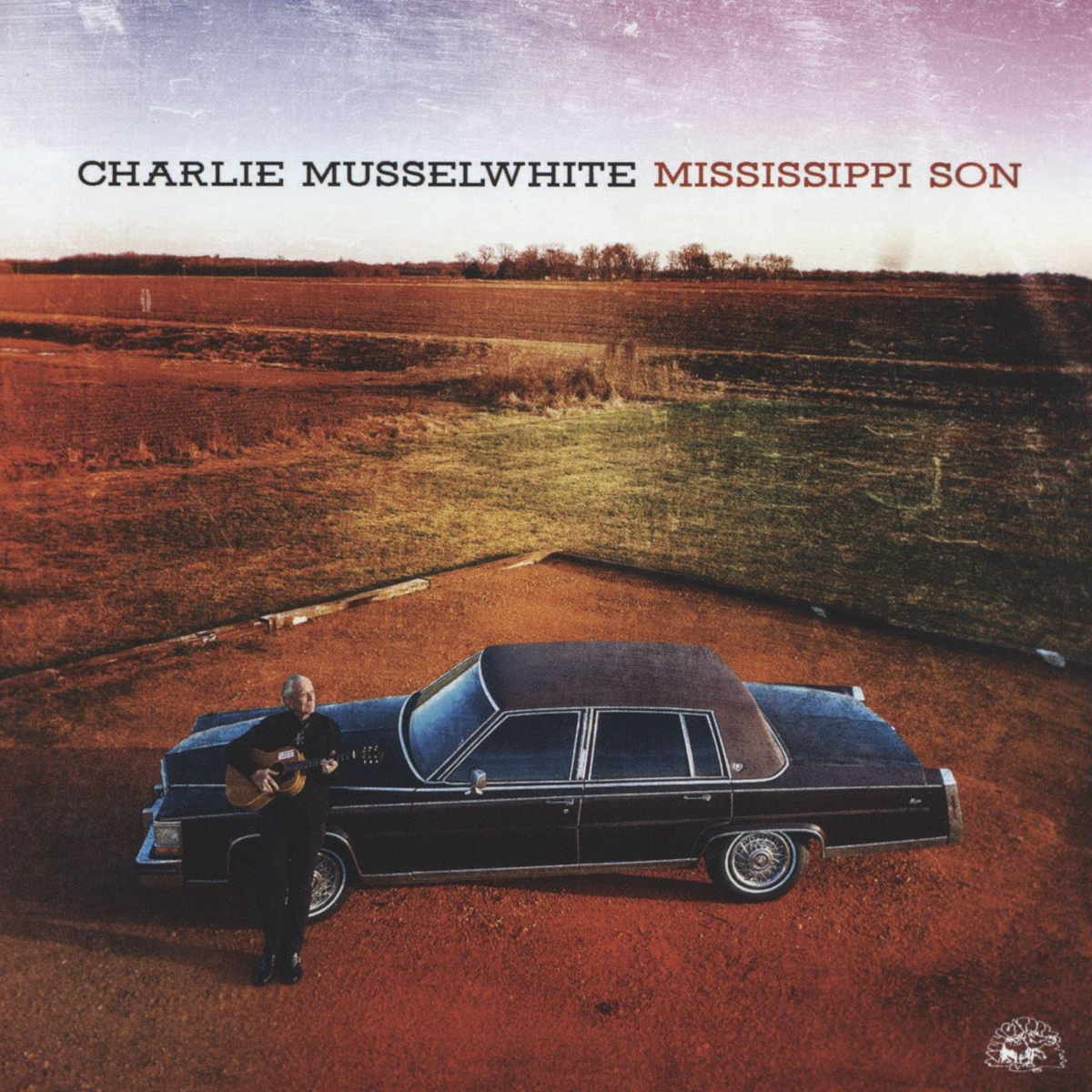

The sight of blues-harp legend Charlie Musselwhite holding a Harmony acoustic guitar on the cover of his 2022 album, Mississippi Son (Alligator), isn’t as incongruous as you might think.

Chances are, if you’ve listened to any of his two-dozen-plus solo albums, you’ve already heard Musselwhite play guitar. But he wouldn’t be offended if you didn’t notice.

After all, harmonica has been his calling card since the 1960s, when he was sitting in with Muddy Waters and other foundational blues artists on Chicago’s South Side.

But throughout his five-decade career in blues music, Musselwhite has snuck a bit of his own fretwork into the mix across most of his albums.

On Mississippi Son, which pays tribute to the music and region that inspired him, he finally brings his guitar playing to the forefront on 14 country blues songs recorded in his adopted Mississippi Delta hometown of Clarksdale, where Son House, Charley Patton, Robert Johnson and other blues greats played.

“The guitar players in my band that I hired, to me they were way better, more modern guitar players than I was,” Musselwhite admits, speaking from his home, which backs up to the languid Sunflower River as it flows through one of the most fertile musical landscapes in America.

“I liked having a guy that could play a strong rhythm underneath me so I can play the harp over the top of that. And a good player makes you play better.”

A good player makes you play better

Charlie Musselwhite

That maxim carries a lot of weight from someone who learned his craft from blues artists who were no more than one degree removed from the originators.

Musselwhite grew up on a dead-end street in Memphis, Tennessee, the only son of a single mother. Young Charlie had ample time to himself, and he used it to explore places like the patch of woods behind his neighborhood along Cypress Creek, where he would lay in the shade and listen to the blues hollers and songs emanating from nearby fields.

“I remember it sounded like how I felt,” he says. “I liked all kinds of music, but blues seemed like there was more to it than just music, and I was really attracted to it because it was comforting. I was a lonely kinda kid and I was left alone a lot. So that was my comfort.”

Musselwhite had already been toying with a harmonica when, at 13, his father gave him a black Harmony Supertone guitar. He learned basic chord shapes from a book, starting with an E chord – “I remember putting my little finger down and making it an E7 and going, ‘Yeah!,’” he says – and then began moving the patterns up and down the neck.

Before long, he kicked off his training wheels and went for it with gusto.

“I just kept experimenting with patterns, and finally I had these patterns where I could go all the way up and down the neck,” he recalls. “I’d play one note and think, Okay, I hear the next note I want. Where is it? I’d find that note, and then I’d find the next note that made sense.

I just kept experimenting with patterns, and finally I had these patterns where I could go all the way up and down the neck

Charlie Musselwhite

“So I would create these scales – I guess you call them modes – and that was the beginning of figuring out how it works.”

Musselwhite’s guitar education accelerated once he began hanging around Beale Street, the main artery of the city’s African-American community, and meeting like-minded musicians and blues elders around town.

A mutual friend introduced him to influential bluesman Walter “Furry” Lewis, and he met Earl Bell and Will Shade of the Memphis Jug Band, as well as Memphis Willie Borum.

“Furry was a friend,” he says. “I would go over to his home, and sometimes we just listened to the ball game on the radio or something. But often I’d ask him to show me things, and he was eager.

“All those guys were flattered that I would come to them and spend time with them, and they thought it was great that I wanted to learn their music and that I respected them and their music. And so it was good for them. And it was good for me.”

The first thing Lewis showed Musselwhite were alternate tunings: open G, or Spanish, and open D, which he called Sebastopol. They unlocked a mystery he’d carried since watching a man play blues under a Summer Avenue overpass years earlier.

He’d been vexed, unable to figure out how the chord shapes and licks he’d committed to memory didn’t sound the same as they did under the bridge. Now he had the key.

Like his Memphis mentors, Musselwhite doesn’t use a pick when he plays. He tried to use a flatpick once, but it didn’t gel with his playing style. He also tried a thumbpick, but it was so inconsequential to his playing that when it disappeared, he never bothered to get another.

Naturally, he goes about it in his own way.

“When I first started teaching myself guitar, I noticed other people would turn their hands so they strummed up with their index finger,” he explains. “But to me, it made sense to use my index finger on the little E, my middle finger on the B string and my ring finger on the G string, and I would pick up, backward from the way they picked.

“I’ve had guitar players that are light years ahead of me on technique say, ‘Man, I could never play like that!’” He laughs. “And I didn’t really know what I was doing. I was just making it up as I went, and that’s what I came up with.”

Soon, Musselwhite set aside what he learned and headed north to Chicago like thousands of others, looking for better jobs than laying concrete in the sun for a buck an hour.

He started driving for an exterminator and learned the city quickly on his routes. He also saw flyers and posters advertising performances by blues artists whose names he already knew well.

“I remember going out 43rd Street, past Pepper’s Lounge, and it said ‘Muddy Waters’ on the window,” he says. “I thought, Damn! I couldn’t believe it. “I saw signs for Elmore James and Howlin’ Wolf, and I was like a kid in the candy store.”

Musselwhite began to write down the addresses, and he would show up after his shift and spend the night watching his heroes paint the walls blue with music.

I saw signs for Elmore James and Howlin’ Wolf, and I was like a kid in the candy store

Charlie Musselwhite

He didn’t tell anyone he played harp or guitar – he wasn’t even legally old enough to be there – but after he’d requested songs from obscure 78s and become a regular, a Pepper’s waitress bragged to Waters that he should hear Memphis Charlie blow harp. So he did.

“That changed everything, ’cause Muddy insisted that I sit in, which wasn’t unusual,” he says. “Guys sat in all the time with other musicians. Playing ’til four in the morning, that’s a lot of time to keep playing music, so Muddy’s always inviting musicians to sit in.”

After hearing him play with Waters, other musicians began offering him gigs. “I couldn’t believe it. ‘You’re going to pay me to play harmonica?’ Boy, that got me focused. That was my ticket out of the factory.”

Eventually, it became his ticket out of Chicago. Although he wasn’t looking to leave, a radio station in San Francisco had started to play a record he recorded for Vanguard, his 1967 debut, Stand Back! Here Comes Charley Musselwhite’s Southside Band.

Offers for gigs followed at ballrooms and auditoriums that paid many times what he could make in the blues clubs on the South Side. He put together a band, lit out for the Bay Area and never looked back.

So many steps in Musselwhite’s career seem like happenstance.

Once he moved to Clarksdale in 2021, where he could be near extended family and just a two-hour drive from his birthplace in Kosciusko, he began to hang out at a studio owned by musician Gary Vincent a few blocks away. The sessions, he says, were a complete accident.

“I was just showing what I do on guitar, and he said, ‘You know, we should tape these,’” Musselwhite recalls. “It wasn’t like it was a plan; it was just another one of those things. It just happens. I wasn’t trying to be flashy. I wasn’t thinking about radio play or nothing like that.”

At first, Musselwhite wasn’t even planning to add harmonica parts, but after cajoling from Vincent, he overdubbed his signature harp.

I wasn’t trying to be flashy. I wasn’t thinking about radio play or nothing like that

Charlie Musselwhite

“It was easy for me because I knew the songs and I knew how to play with the guitar I was playing and accompany myself.”

Mississippi Son turned into a semi-autobiographical song cycle of 10 original songs and four covers, including Delta blues re-imaginings of the Stanley Brothers tune “Rank Strangers” and Guy Clark’s “The Dark.”

Played as solo excursions or in a trio format with upright bass and a small drum kit, the songs unfold under Musselwhite’s frank, storyteller vocals, with harp and fingerstyle guitar flourishes.

Musselwhite also pays tribute to his Chicago roommate and rambling partner Big Joe Williams with the solo acoustic “Remembering Big Joe.” It’s an improvised blues inspired by and played on one of Williams’ guitars, a nine-string instrument – his preferred configuration – which Williams fashioned by nailing a piece of metal with three tuning pegs across the top of the headstock.

A mutual friend had inherited the instrument and brought it to the studio where Musselwhite was recording Mississippi Son. Perhaps not knowing what he had, he reverted the guitar back to a six-string.

“Joe would double the little E and the B and the D,” Musselwhite says. “The G string was not doubled, but he always played an unwound G.

In Memphis, I remember the brand of strings we all used was Black Diamond, and you’d take out that G string and it’d be wound, and you put the end of it under your foot and take a knife and just scrape all that stuff off so you had an unwound G. ’Cause it’s cool to bend it in the middle of a chord, you know?”

For Mississippi Son, Musselwhite relied mostly on a 1954 Gibson J-45 and a 1967 Silvertone, although his tastes run even more eclectic.

One of his favorites is a Harmony Stratotone, which he picked up while working with Tom Waits in the ’90s.

Marc Ribot said, ‘You know, it’s really the only guitar worth having... And I thought, I’m getting me one!

Charlie Musselwhite

“I was on tour with Tom Waits, and I was backstage,” he begins. “He had two guitar players with him – Marc Ribot and Smokey Hormel – and they both had Stratotones, and they were talking about how much they liked them.

“And I’m just listening, and at one point Marc Ribot said, ‘You know, it’s really the only guitar worth having.’” He laughs. “And I thought, I’m getting me one!

“That’s just a hell of a guitar,” he adds. “I love the tone on it, and I love that fat neck, ’cause you can really dig in. I’ve played these guitars that are really finely made, with the shaved-down neck and everything, and they’re too delicate. I can’t play those things.”

Ultimately, it’s just as well, because Musselwhite has never had an interest in being a speed demon. His raw, gutbucket style of playing requires a sturdy instrument he can wrangle.

“I never really tried to or had any interest in being like a shredder.” He laughs again. “Or a rocker, or anything like that. I didn’t ever have any desire to get a big amp and conquer the world shredding guitar.

“I just liked the feeling and the subtleties and the substance of the original down-home blues, and that’s what I’ve always wanted to play. And if I never ever had a career at all, that’s what I would be playing anyhow, for myself.”

Order Charlie Musselwhite’s Mississippi Son here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jim Beaugez has written about music for Rolling Stone, Smithsonian, Guitar World, Guitar Player and many other publications. He created My Life in Five Riffs, a multimedia documentary series for Guitar Player that traces contemporary artists back to their sources of inspiration, and previously spent a decade in the musical instruments industry.

"I thought, 'Jeez, how the hell did he do that?'" Phil Manzanera on the tone, tuning and technique of his teenage friend David Gilmour

“I felt so crestfallen. I wanted to throw my guitar away.” Alex Lifeson on the gig that made Rush feel like they’d made it — and how one audience member brought them crashing down to Earth