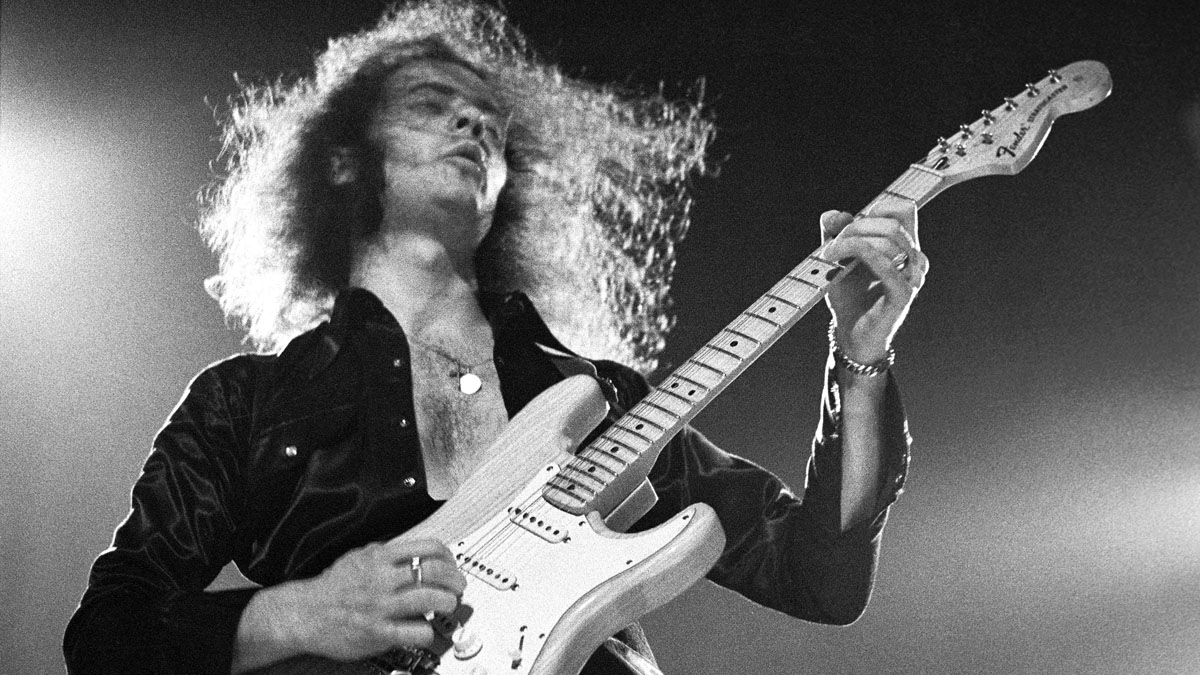

The Unstoppable Rise of Ritchie Blackmore and the Making of 'Deep Purple in Rock'

How the maniacal mind and guitar mastery of the Man in Black created a hard-rock masterpiece.

Deep Purple in Rock is many things, but subtle is not one of them. Within literally seconds of listening to it, you’re blasted by Ian Paice’s frantic, slippery drums, Jon Lord’s braying organ, and, of course, Ritchie Blackmore’s indelible guitar riffing and loopy tremolo flourishes.

Along the way, singer Ian Gillan references and rearranges rock’s DNA (“‘Good golly!’ said little Miss Molly/When she was rocking in the house of blue light!”), punctuating his Little Richard and Elvis Presley–inspired lyrics with ridiculously piercing and forceful shrieks and wails. For that matter, the frenzied rhythm, developed by bassist Roger Glover, emulates Jimi Hendrix’s “Fire.”

From there, we’re through two verses and choruses and on to bearing witness to a classic Lord–Blackmore organ-guitar battle. And we’re only a minute into the record. The song we’re listening to is called “Speed King,” and it’s a wild and breathless launch to In Rock.

It’s also completely in line with what ensues over the next 40 minutes or so. From the snaky, metallized grind of “Bloodsucker” to the breakneck gallop of “Flight of the Rat,” the monolithic guitar-organ groove of “Into the Fire,” and the thundering “Hard Lovin’ Man,” the album is a relentless sonic juggernaut, its massive and over-the-top sound reflected in both the album title and the Mount Rushmore–aping cover art.

In fact, the only moment where Purple drive the music with anything less than the pedal fully floored is the 10-minute epic “Child in Time.” And given the fact that Gillan refuses to sing this one onstage anymore due to the practically inhuman vocal demands (there’s also an explosive, elongated Blackmore solo that many consider one of his best), this might be the most intense track of all.

“If it’s not dramatic or exciting, it has no place on this album,” Blackmore once said of In Rock, and we’d be loath to disagree. There’s nary a moment on the record that isn’t a full-on white-knuckled experience.

But we’d also add the word heavy to the first part of Blackmore’s statement. Because even today, 50 years after its original release, In Rock is a testament to just how intense (and, per Ritchie, dramatic and exciting) guitar-based rock and roll can be. A half-century ago? It sounded positively revolutionary.

If it’s not dramatic or exciting, it has no place on this album

Ritchie Blackmore

The album arrived at a turning point in popular music culture. The ’60s were, chronologically and spiritually, over. Woodstock had given way to Altamont, the Beatles were on the brink of breakup, and free love and the hippie dream had morphed into something darker and less idealized.

There were heavy bands, but many of them – Cream, Jimi Hendrix, Vanilla Fudge, Blue Cheer – were either dissolved or on their last legs. Into this moment stepped three British acts – Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, and Deep Purple – that would push hard rock to new extremes and influence the generations of bands that were to follow.

By 1970, Zeppelin had established themselves as the preeminent hard-rock outfit, with two blockbuster albums under their belt and a third brewing that would delve more deeply into the band's folk and acoustic roots.

Black Sabbath, meanwhile, were crafting a doomy and downtuned sound that, paired with Ozzy Osbourne’s desperate wail and an overall exaggerated evil atmosphere, established the template for heavy metal going forward. And then there was Purple. By 1970, they were already, by the relatively brief lifespan of rock bands at the time, something of a veteran act.

They had released three albums – 1968’s Shades of Deep Purple and The Book of Taliesyn and the following year’s Deep Purple – and scored hits (at least in the U.S., where they were bigger than in their native U.K.) with covers of Neil Diamond’s “Kentucky Woman,” Ike & Tina Turner’s “River Deep – Mountain High,” and, most notably, Joe South’s “Hush,” which climbed to Number Four in the U.S. in the summer of ’68.

Of course, while that band was very much Deep Purple, it was not the decibel-defying, instrument-destroying, amp-exploding act that laid waste to arena and festival stages throughout the early and mid ’70s.

Nor was the Ritchie Blackmore of this Deep Purple the wild-eyed-but-cool-as-ice Fender Stratocaster–wielding, neoclassical-guitar-pioneering, whammy-bar-abusing six-string hero he would come to be praised as. That all began, unequivocally, with In Rock.

When I was attending school, I was constantly practicing mentally. Then I would rush home and practice until the early hours. I would practice about five hours a day. I was obsessed with playing

Ritchie Blackmore

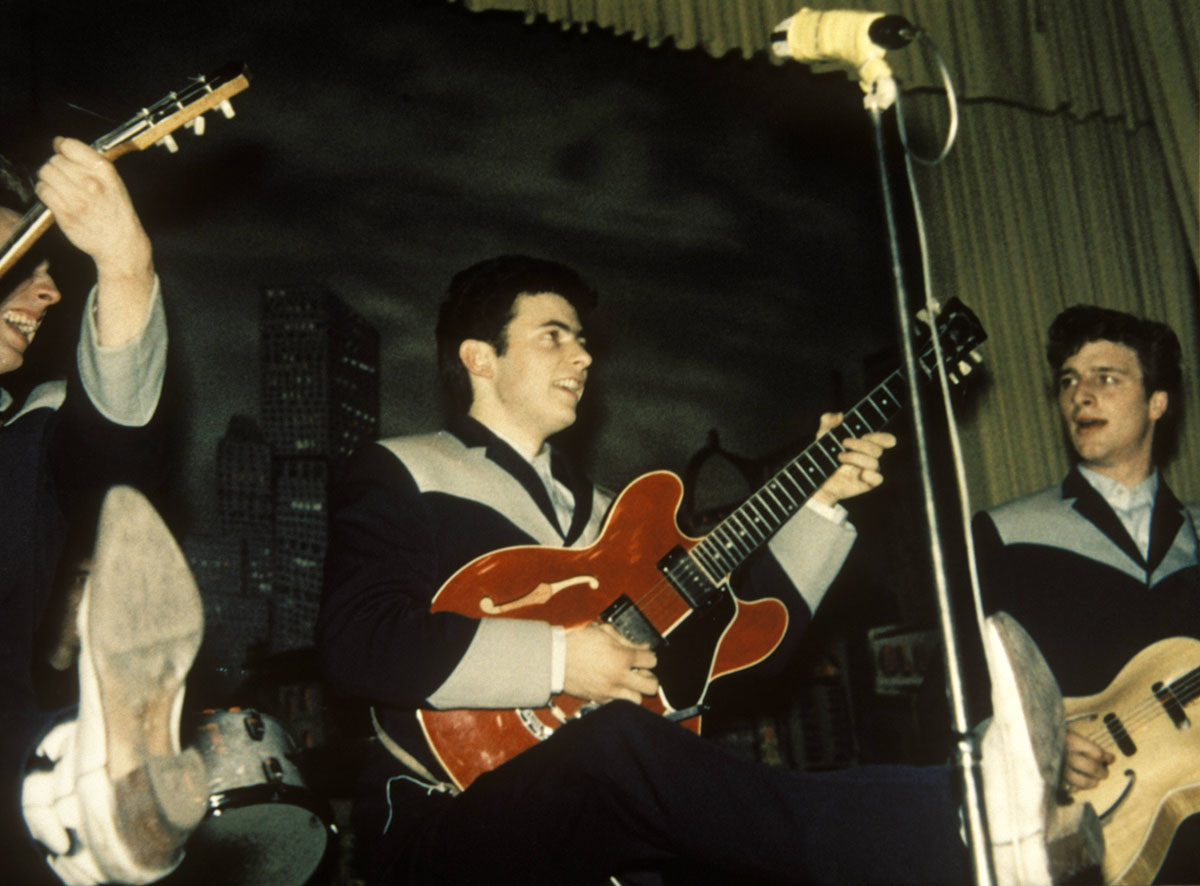

Back in 1968, however, Deep Purple were a fledging act led by Blackmore and Lord, the latter a classically trained pianist who had already logged years of recording, performing, and session work (he claimed to have played organ on the Kinks’ 1964 hit single “You Really Got Me”).

Blackmore, for his part, had spent time with a variety of acts, including the Outlaws, Neil Christian, and the outrageous “horror-rocker” Screaming Lord Sutch.

He also worked as a session guitarist around London and had, in his younger days, taken lessons from British session ace Big Jim Sullivan, who lived near Blackmore and was at one point in the mid ’60s considered the top session man on the circuit alongside the likes of Jimmy Page.

“He was teaching me classical – Bach, and things like that – and he was teaching me to read better than I was,” Blackmore said of Sullivan. Like Page and many other British guitarists of the time, Blackmore cut his teeth on a wide variety of sounds and musical styles. He once called 1950s British teen idol and skiffle player Tommy Steele his “first hero.”

Seeing Steele on a TV show titled Six Five Special, Blackmore recalled saying to himself, “That’s what I want to do: I want to jump around with a guitar like Tommy Steele does. I don’t want to play it, necessarily. I just want to jump around with it, like he did.”

From there, Blackmore dove deep into guitar, immersing himself both in classical forms as well as in the playing of Hank Marvin, Les Paul, Django Reinhardt, Wes Montgomery, Scotty Moore, and Cliff Gallup.

His style, he said, “developed through sheer practice. When I was attending school, I was constantly practicing mentally. Then I would rush home and practice until the early hours. I would practice about five hours a day. I was obsessed with playing.”

By 1967 Blackmore, with his ever-present Gibson ES-335, had made a name for himself around London both as a performer (Screaming Lord Sutch, he said, “pulled me out front and demanded I jump around and act stupid”) and session man (“It was funny sometimes to hear yourself on perhaps eight out of 10 records being played on the radio”).

He was doing an extended stint gigging in Hamburg when he received a call to come back to England to audition for a burgeoning project conceived by British drummer Chris Curtis named Roundabout, which also included Jon Lord among its ranks. Curtis soon exited the project, and the band was rebuilt around Blackmore and Lord, who had found common ground upon meeting.

Jon and I both had classical leanings. He more so than I, so we had something in common immediately

Ritchie Blackmore

“Jon and I both had classical leanings,” Blackmore said. “He more so than I, so we had something in common immediately.” Eventually they added bassist Nick Simper and, after some musical chairs, singer Rod Evans and drummer Ian Paice, who had played together in a band called the Maze.

It is this lineup that began gigging as Roundabout, and, soon enough, as Deep Purple, after Blackmore suggested they rename the band after his grandmother’s favorite song, a 1930s-era standard that had been covered by various big-band and pop artists over the decades.

But there was also another consideration: “There were lots of ‘color’ bands around – Moody Blues, Pink Floyd, et cetera,” Blackmore explained. “Colors were in!”

By the summer of ’68, the new band had released its debut, Shades of Deep Purple, on EMI in the U.K. and Tetragrammaton Records (a brand-new label co-founded by comedian Bill Cosby) in the U.S., and notched a quick hit in the latter region with their organ-forward version of “Hush.”

Over the course of Shades and their next two records, Purple veered between pop, blues, rock, psychedelia, ballads, and baroque elements, without quite managing to carve out a distinct sound. Blackmore has acknowledged as much.

“I’m not particularly proud of the first three records,” he admitted. “They seem to be meandering all over the place. We didn’t really have a niche and we didn’t quite know where we were going.”

Unsure of their musical footing, facing declining sales after “Hush” and dealing with the demise of Tetragrammaton, which went broke and folded soon after the release of Deep Purple, the group knew a change was in order.

People were confused about what kind of band we were. Blackmore firmly stepped up and changed the band’s identity into a jamming, hard-rocking force

Roger Glover

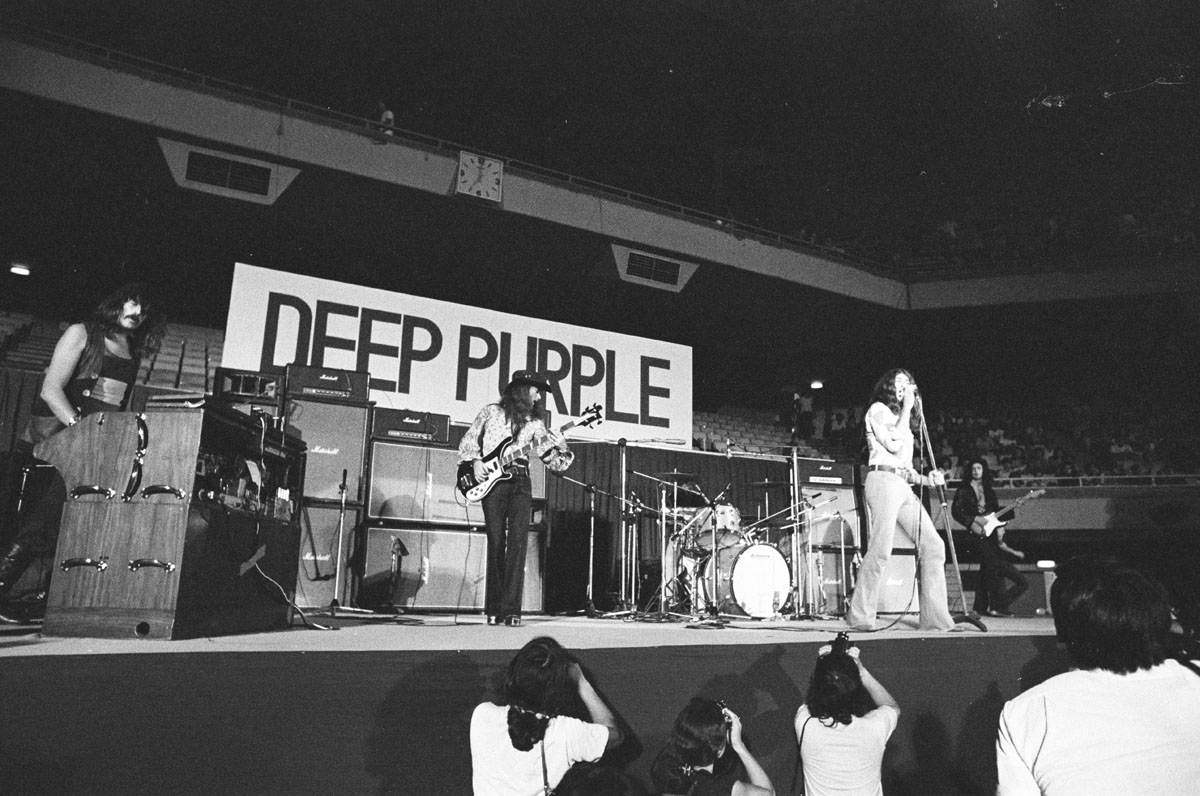

Inspired in part by Zeppelin, Blackmore and Lord opted to take Purple in a heavier, more hard-rocking direction, and got Paice onboard with the idea. Their singer and bassist were less agreeable.

“We thought that Rod and Nick had gone about as far as they could,” Paice said. “We decided that if it was going to be a break, it was going to be a substantial one to refocus the band to look forward, to break this feeling of stagnation.”

Which is exactly what they did with the addition of leather-lunged vocalist Ian Gillan and bassist Roger Glover, both of whom hailed from British band Episode Six. Like Purple, Episode Six had struggled to break through to a wider audience. And like their soon-to-be bandmates, Gillan and Glover had grown tired of waiting for it to happen.

Thus, the classic Purple lineup, henceforth known as Deep Purple Mark II, was born. And while the intention all along had been to go in a heavier direction, ironically, the first fruits of their labors – the rather tame 1969 single “Hallelujah,” followed by the Jon Lord–spearheaded live classical album Concerto for Group and Orchestra – were quite the opposite. Blackmore, for one, was not amused.

In the wake of Concerto, “The split between the musical side of Jon and the harder side of Ritchie came to a head,” Paice said. “Concerto for Group and Orchestra was Jon Lord’s baby,” Glover observed. “People were confused about what kind of band we were. Subsequently, Blackmore firmly stepped up and changed the band’s identity into a jamming, hard-rocking force.”

The result of that step-up was In Rock. “That record was sort of a response to the one we did with the orchestra,” Blackmore said. “I wanted to do a loud, hard-rock record. And I was thinking, This record better make it, because I was afraid that if it didn’t we were going to be stuck playing with orchestras for the rest of our lives.”

With In Rock, Blackmore recalled, “Ian Gillan and Roger Glover had come in, so that gave us new blood. I found my niche being much heavier music and playing with more sustain on the amplifier – that sort of thing. We consciously sat down and said, ‘Let’s have a go at being really heavy.’”

I found my niche being much heavier music and playing with more sustain on the amplifier. We consciously sat down and said, ‘Let’s have a go at being really heavy’

Ritchie Blackmore

But before the heavy new Purple hit the studio, they hit the road. Much of the material that would feature on In Rock was worked up onstage by the nascent lineup.

A bootleg from an August 1969 gig at Amsterdam’s Paradiso – only the band’s seventh gig with Gillan and Glover – shows early versions of “Speed King” (then titled “Kneel and Pray”) and “Child in Time” were already in the set. A review of the gig described the chaos of those formative days, noting that, during the former song, “the whole stage seems to be in a state of general mayhem.”

But the stage was also paramount to the development and eventual sound of In Rock. Said Gillan, “If you’re going to write about In Rock, you’ve got to combine the making of the album with the live performances. They were so much more important than the actual making of the record. Making records is almost an inconvenience, because you have to compromise in the studio.”

And while the combination of new members sparked a surge in writing – Gillan once remarked that he didn’t even know how “Speed King” happened – Glover also singled out Blackmore for being particularly inspired at the time.

“Ritchie wasn’t just the guitar player,” the bassist said. “He was a brilliant innovator. Things he wrote defy description. He was a magnetic, dynamic writer. I don’t think he could have done it in a vacuum by himself; it did require the rest of us. But I’ll certainly give him his due. He was the motivating character in the band.”

While In Rock serves as a showcase for every member of Deep Purple, it is without a doubt Blackmore who makes the biggest impression.

Ritchie wasn’t just the guitar player. He was a brilliant innovator. Things he wrote defy description

Roger Glover

While his riffing and rhythm playing is rock solid and infused with plenty of attitude and aggression (“Bloodsucker” practically verges on heavy metal), it is in his lead work that the guitarist truly shines, mixing classical-tinged technique (the explosive triplet pattern that caps the dramatic “Child in Time” solo), deft, intricate runs (“Flight of the Rat”), insane whammy-bar warbles and plunges (“Bloodsucker”), and barely controlled noise (“Hard Lovin’ Man”) into an approach that manages to sound both studiously technical and completely unhinged. Blackmore was clearly, as intended, taking his playing in a harder-edged direction.

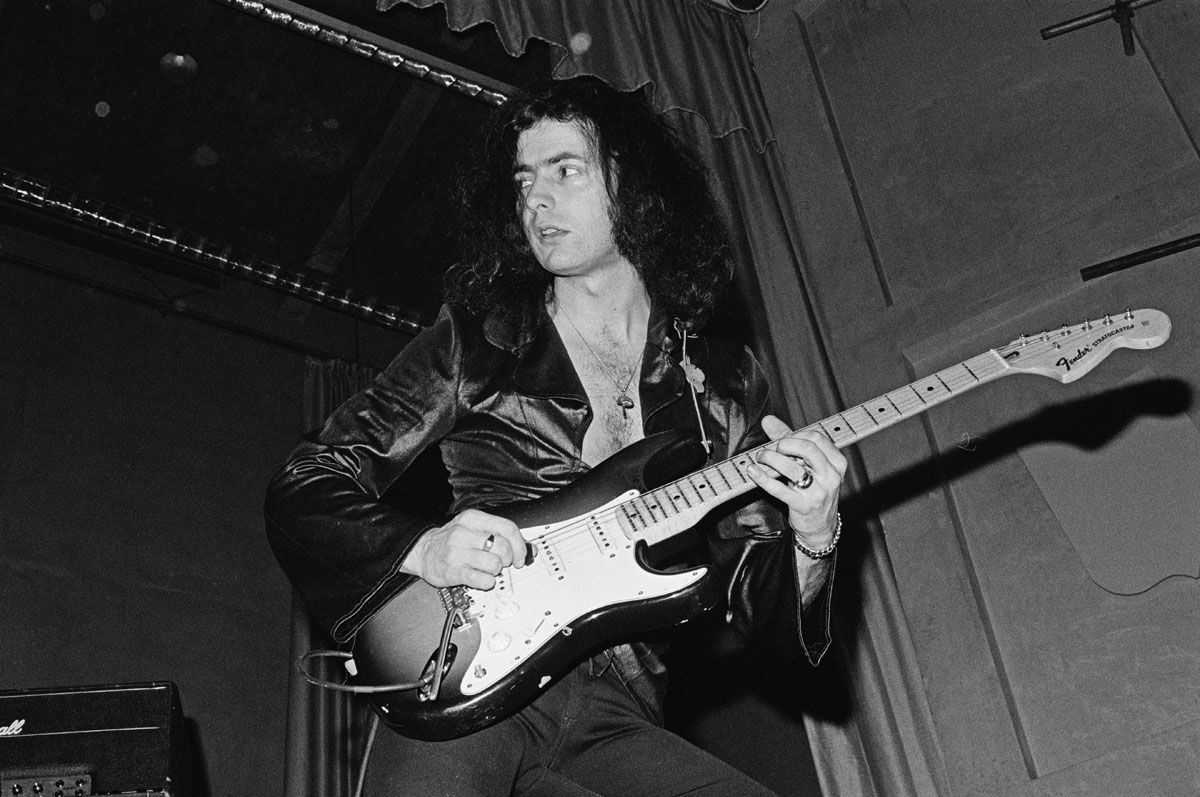

But there was more to his stylistic shift on In Rock than merely changing up his approach. Just as significantly, he also overhauled his gear. Around this time, the guitarist traded his stalwart ES-335 for a new number-one guitar, a Fender Stratocaster.

“I liked the way Hendrix’s Strat looked,” he explained. “A Strat has got that rock kind of look. So the visual thing attracted me first, even though it was an upside-down Strat in Hendrix’s case. I thought, I must try one of those someday.”

As for where he got his first Strat? “I knew Eric Clapton’s roadie. He was a friend of ours. And I think Eric had given him one of his Strats as a present. Probably because Eric didn’t want it. I think it had a slightly bowed neck, which was making the action pretty high. [The roadie] said, ‘I’ll sell it to you for £60.’ So Eric Clapton’s throwaway Strat came in handy for me.”

I changed to a Stratocaster because the sound had an edge to it that I really liked. But it was much harder to get used to... Every note counts; you can’t fake a note

Blackmore used both the Fender and the Gibson on In Rock – “Child in Time” and “Flight of the Rat,” at least, are Blackmore on the ES-335. But it is the Strat, and in particular the guitar’s tremolo, that would come to dominate his sound.

“I changed to a Stratocaster because the sound had an edge to it that I really liked. But it was much harder to get used to,” he said, noting, “when you’re playing a humbucking pickup, you’ve got that fat sound, and it’s quite forgiving. But when you play with Fender pickups, they are so thin and mean and edgy and hard. And every note counts; you can’t fake a note.”

While the Strat didn’t allow Blackmore room to “fake a note,” it did make it possible for him to bend, bow, wobble, and whammy the heck out of them.

Which, of course, Blackmore did, making extreme trem abuse a cornerstone of his playing beginning on In Rock, and then throughout the rest of his ’70s work with Purple. To be sure, Blackmore was hardly polite in his approach to the whammy bar. Rather, he said, “I went crazy with it. I used to have quarter-inch [vibrato] bars made for me because I’d keep snapping the normal kind.

My repairman would look at me strangely and say, ‘What are you doing to these tremolo bars?’ Finally, he gave me this gigantic tremolo arm made of half an inch of solid iron and said, ‘Here. If you break this thing, I don’t wanna know about it!’

“About three weeks later,” Blackmore continued, “I went back. He looked at me and said, ‘No – you haven’t.’ And I said, ‘Yes I have.’ In graphic detail, I explained to him how I would twirl the guitar around the bar, throw it to the floor, put my foot on it and pull the bar off with two hands. He was a bit of a purist, so he wasn’t amused.”

Blackmore’s whammy bar makes itself known less than 20 seconds into In Rock, with a loopy dip signaling the first chorus (and every subsequent one) of “Speed King.”

I got this urge and started rubbing the guitar up and down the doorway of the control room to get all that wild guitar noise. So this bloke looks at me, and he’s got this expression on his face as if I’d lost my mind

But he really leans into the bar on tracks like “Bloodsucker” and, in particular, the tour de force finale, “Hard Lovin’ Man,” which closes with roughly a minute and a half of pure six-string guitar mayhem, with Blackmore unleashing shredding licks as he pummels his tremolo, violently scrapes his strings, and conjures all manner of screaming feedback.

His bandmates, seemingly unable to keep up, eventually drop out of the mix, then return and drop out again, leaving Blackmore to finish the song – and the record – on his own, going out in a hail of guitar screeches and moans and white noise.

It is a literally show-stopping end to the record, and stands as arguably one of the most beautifully unhinged recorded guitar moments of the era. “One of the engineers who originally worked on that album was this stuffy bloke who didn’t like rock and roll music,” Blackmore recalled.

“While I was recording the solo on that song, I got this urge and started rubbing the guitar up and down the doorway of the control room to get all that wild guitar noise. So this bloke looks at me, and he’s got this expression on his face as if I’d lost my mind.” Of course, Blackmore could also be subtle and nimble when the part called for it.

Take the long break in “Child in Time,” which sees him building something of a composition within a composition, his solo beginning with round-toned, bluesy phrases accented with moaning note bends, before gradually picking up speed, taking on a biting, snarling sound and exploding in a flurry of classical arpeggios.

It’s one of his most celebrated and complex solos, and what’s more, Blackmore said years later, he would sometimes play it much faster onstage.

Jon was able to match Blackmore’s massive guitar sound and transform the organ from a polite instrument and stand toe-to-toe with a guitarist as overpowering as Blackmore

The only problem, he admitted, “was coming into that part at the end of the guitar solo that the band would do in unison. You can only play that so fast – unless you start tapping, which I don’t do, out of principle. It’s just an A minor arpeggio, but it’s all downstrokes. You try and play that really fast after you’ve had 10 scotches!”

Then there’s “Living Wreck,” where he constructs his solo almost entirely of long, vibratoed notes played in phrases that slowly make their way up the fretboard to reach a climactic end. The result is a passage that sounds almost violin-like in tone and texture, and contrasts with the distorted organ bleats that otherwise characterize the song.

That push and pull between Lord’s organ and Blackmore’s guitar, it’s worth noting, would become a key component of Purple’s sound. And once again, it all began on In Rock.

As Roger Glover once explained, “Jon played the blues when he was young, and that gave him a solid foundation, because when he played hard in Deep Purple, he was able to match Blackmore’s massive guitar sound and transform the organ from a polite instrument and stand toe-to-toe with a guitarist as overpowering as Blackmore.”

One way Lord did that, Glover continued, was by “abusing his instrument and sticking it through a Marshall instead of a Leslie to make it scream.”

For the first probably five years of Deep Purple – ’70 to ’75 – I did have the loudest amp in the world

Ritchie Blackmore

Which was useful, as Blackmore tended to play loud. “I’ve always played every amp I’ve ever had full up, because rock and roll is supposed to be played loud,” he told Guitar Player in 1973. “Also, keeping the amp up is how you get your sustain. I turn down on the guitar for dynamics.”

Blackmore has always been a bit cagey when it comes to discussing his exact amp setup back in the day, though it is common knowledge that in the early ’70s he was fond of both Vox and Marshall units.

Eventually, he moved on to Marshall Majors, which he had modded with an extra output stage to give the amp “a fatter sound, a bit more distorted,” he said.

“This extra output stage basically made the 200-watt into a 280-watt. So for the first probably five years of Deep Purple – ’70 to ’75 – I did have the loudest amp in the world.” No matter what amp he was using, however, a mainstay of Blackmore’s rig in those days was the Hornby-Skewes treble booster.

“That is the sound I always used, coupled with the Vox or the Marshall,” he said. “For a while, Jon Lord used the Hornby-Skewes and Marshall for his organ as well. We were looking for a distorted organ sound and I said, ‘Why don’t we plug your organ through my Hornby-Skewes and into my amp and see how an organ sounds like that?’ So we did it, and of course he loved the sound.”

And what’s not to love, really? The massive sound that Deep Purple forged on In Rock, and then carried through on subsequent early ’70s masterpieces like Fireball and Machine Head, would inspire and spawn literally generations of hard-rock and heavy-metal bands.

One future guitar hero who found it impossible to look away from Blackmore was virtuoso neoclassical shredder Yngwie Malmsteen, who is clearly indebted to the Purple man in terms of sound, style, and even choice of instrument. In a call with Guitar Player, he was eager to testify to the greatness of Blackmore and the band on In Rock.

Everybody talks about Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath, and I love those bands, too. But 'In Rock' is heavier and more metal than any of the other guys

Yngwie Malmsteen

As a child growing up in Sweden, Malmsteen said, “Hearing In Rock was like taking a brick and just shoving it right in your head. It’s heavy, it’s fast, it’s technical, it’s sick. It’s a really, really aggressive sound. ‘Flight of the Rat,’ ‘Child in Time,’ ‘Into the Fire’… It’s timeless. It’s ridiculous.”

Following In Rock, Deep Purple, of course, went on to experience greater highs (there’s that little Machine Head ditty “Smoke on the Water” for one), and also incredible lows.

To the latter point, there is the rift that has lasted for decades between Blackmore – who now focuses primarily on acoustic Renaissance music, as well as occasionally playing with his reunited post-Purple act, Rainbow – and his former bandmates.

In fact, when Purple were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Blackmore, depending on who is telling the story, either declined or was prevented from standing alongside them to accept the honor.

As Glover said in a 2018 interview, “He can be difficult to work with, but he is even more difficult to live with. Blackmore is a very unique character, and in the early days we had fantastic times and wrote great songs.”

Indeed they did, and many of Purple’s greatest are collected on In Rock, which, 50 years on, is still as alluring, mesmerizing, and flat-out overwhelming as ever. It’s the album, as Blackmore has said, where “everything clicked” for Deep Purple.

Or, as Malmsteen says, “It’s the one where they go full out the most. Everybody talks about Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath, and I love those bands, too. But In Rock is heavier and more metal than any of the other guys.

"It was just, ‘Turn everything up and play as fast and as loud and as much as you can!’” He laughs. “I was eight years old when I heard it, and it messed with my head forever. Because I still do that!”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

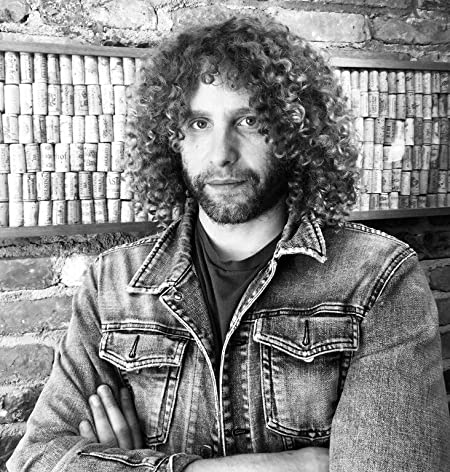

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.

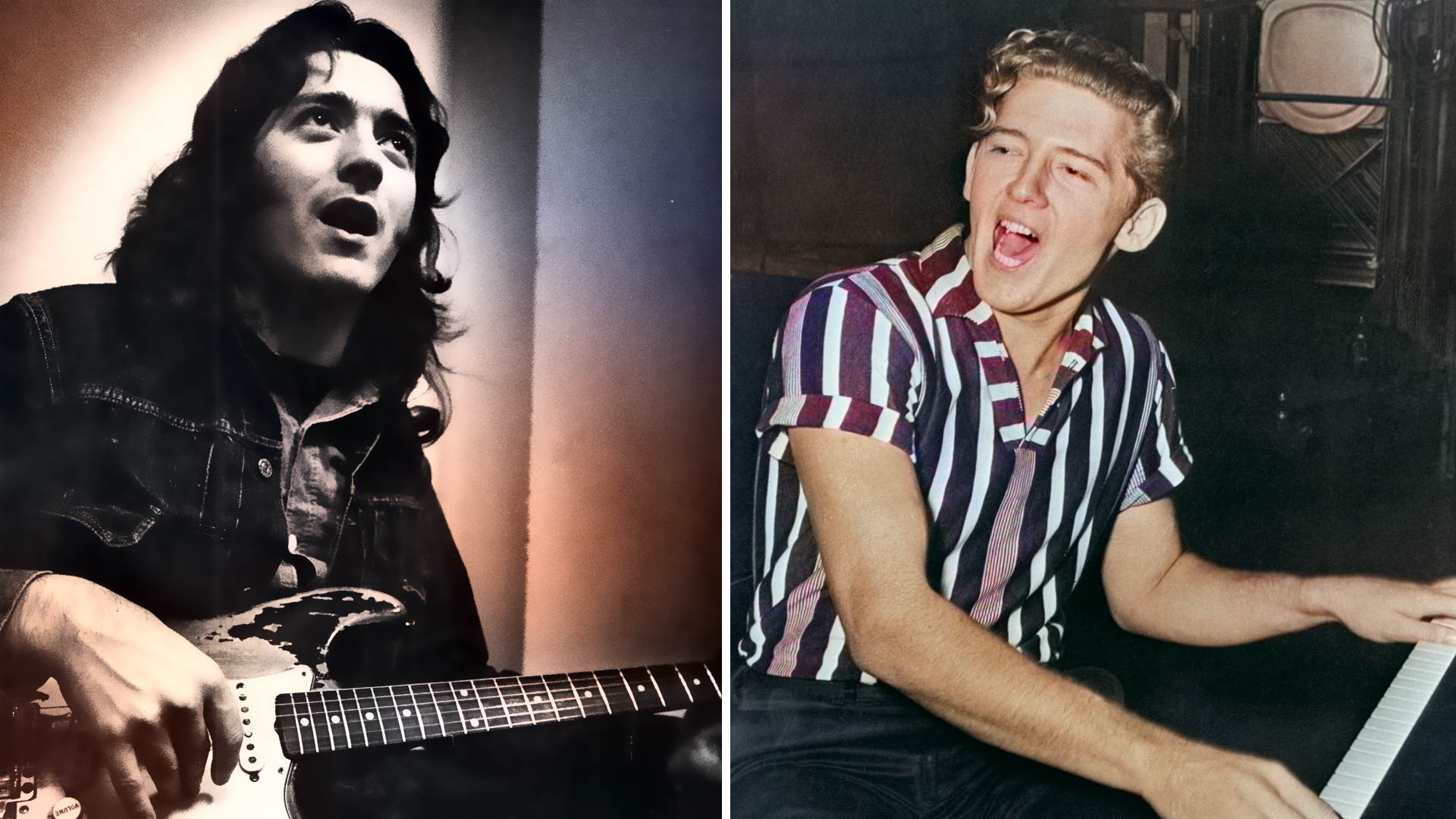

"Slide? I flipped the bird a lot when I was a kid, so I just naturally put that to use…" Bonnie Raitt started out driving Son House and Skip James to festivals – then she became the biggest female slide player around

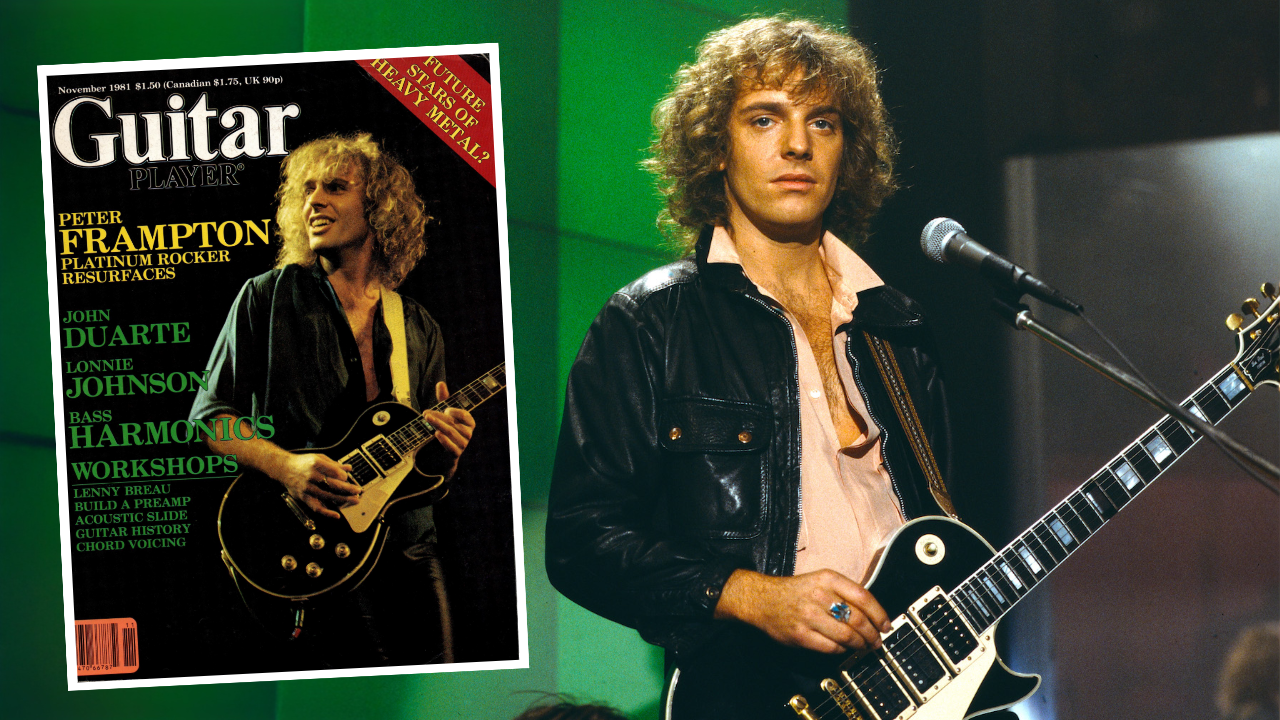

"Very few people can play fast and put feeling into it. A lot of it is just cold technique…" Peter Frampton: The Guitar Player Interview