The Story of Teenie Hodges, Memphis Soul's Greatest Guitar Player

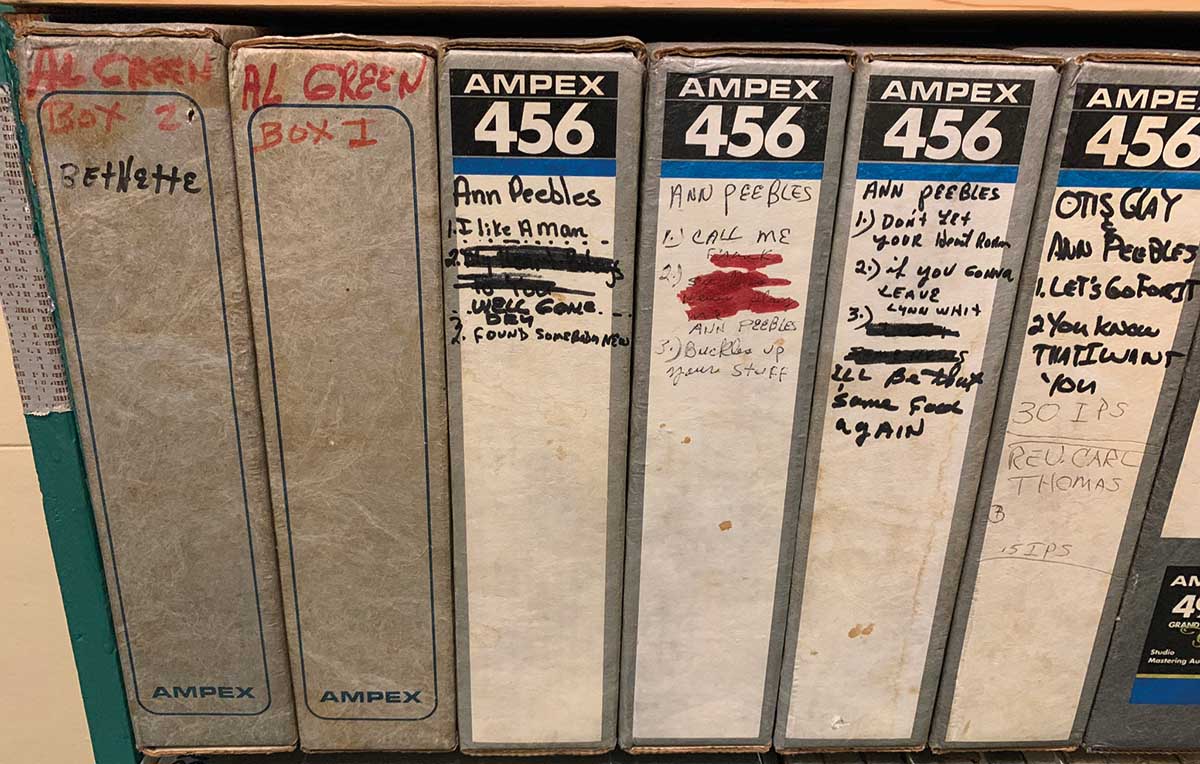

As the guitarist for Al Green, Ann Peebles, and other Hi Records acts, Hodges played from the depths of his heart to the heights of heaven.

He instinctively knew how to come up with the perfect part for a song. And he had his own way of fingering heavenly and earthy voicings that could pull at the heart strings of Memphis’s finest soul singers.

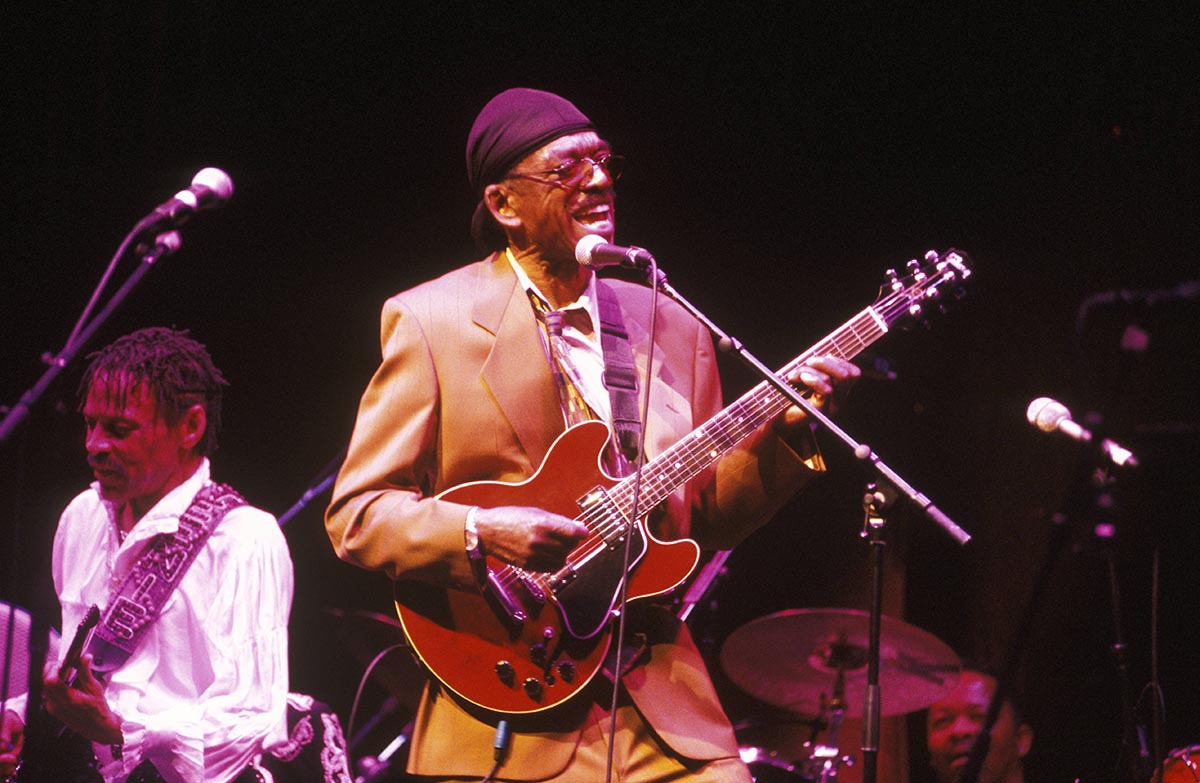

Usually the one to count off a take at Royal Studios, he’d tap his foot on a Coca-Cola crate and lead the Hi Rhythm Section into playing so seductively deep in the pocket that we still get hooked 45 years later, willing to follow the band wherever it goes. Mabon “Teenie” Hodges was one of the architects of Memphis soul.

Boo Mitchell, producer, owner of Royal Studios and son of legendary producer-arranger Willie Mitchell, remembers Hodges’ unique approach to the guitar. “It was just the way he voiced chords and his fingerings,” Mitchell says. “When he was a teen, he spent a lot of time with my Pop, who was a real stickler with how to voice chords to get the most out of them.”

Mitchell recalls one particular session. “When we cut Boz Scaggs’ Memphis album in 2012, Teenie stopped by for a visit. Ray Parker Jr. was there and asked him how he played the licks on [Al Green’s 1973 hit] ‘Here I Am (Come and Take Me).’ So Teenie is sitting with his guitar and his foot on the Coke crate playing the song, and Ray’s jaw dropped because he never would’ve thought to play it like that.”

“As a brother, he made me proud. And as a musician, he was one of the greatest of the rhythm players,” says Reverend Charles Hodges, organ player with the Hi Rhythm Section. “He had that style, bounce, and soul pocket, which he worked on real hard to create as he was growing up.”

Martin Shore is a drummer, music educator, and director of the 2014 documentary Take Me to the River, which portrays Memphis music legends and sidemen passing on their knowledge to younger artists.

“Teenie had a way of setting a rhythm and locking into this velvety groove. That’s what made Al Green’s stuff so definable,” he says. “He wasn’t the kind of guy who would sit and chat shop with you. But if he heard something, he instinctively knew what to play and how to make it sound tight and right.”

This involved resisting any impulse to change things up. “It always impressed me with all these funk and soul players that it’s not about what they play but what they’re not playing,” Shore says. “The simplicity is about sticking with it and not trying to go somewhere else with it. And I think a lot of musicians suffer from that a little bit.”

That sense of restraint is something that Dustin Barber, Al Green’s touring guitarist since 2007, has picked up on as well.

“Teenie’s parts are super-creative and fun to play,” he says. “Whether it’s fat barre chords, funky rhythms, or R&B fills, he always stayed in the pocket and only played what needed to be there.” North Mississippi Allstars guitarist Luther Dickinson had the opportunity to record with Hodges during the making of Shore’s documentary, and he’s been a long-time disciple of the Memphis soul master.

“The classic Al Green albums are a constant inspiration and blueprint for me,” he says. “I keep that music on my phone at all times. Any time I’m arranging or rearranging a song, I look to ‘Let’s Stay Together’ for feel. I literally try to make everything I do feel like that song. Teenie’s style, playing, and writing are the heart and soul of Al Green’s music.”

Hodges’s playing might be easy to figure out theoretically – blues, major/minor pentatonics, 7th chords, and so on – but his touch, tone, and phrasing are hard to imitate. When asked what defines Hodges’ style and what one would need to emulate him, everybody begins their answer with a chuckle.

“The lick to ‘Love and Happiness’ – nobody ever plays it right!” Mitchell says. “His style was so unorthodox. But that goes for all of those guys [the Hi Rhythm Section]. They didn’t play guitar lesson or music lesson stuff, didn’t go to school for theory. They had a completely organic, unorthodox approach that made their sound unique, gritty, and so soulful. I think a lot of it may have come from gospel and being in the church.”

Adds Shore, “Teenie really personified Memphis music: sophisticated, funky, and joyful, yet there is a little blue tinge to it. And it’s impossible to tap into that deep groove unless it’s coming straight from your heart and soul.”

The key to Teenie Hodges’ sound and style is most likely to be found in the Hi Rhythm Section’s playing philosophy and, as Mitchell points out, how they all started out in music. The Hodges brothers – Teenie on guitar, Charles on organ, and Leroy on bass – were born into a musical family in Germantown, Tennessee, led by their dad, prominent blues pianist Leroy Hodges Sr.

“When Teenie picked up a guitar, I guess he was about 12 or 13 years old. He was self-taught,” says Charles Hodges, who still is an active session player in Memphis today. “One of his mentors, [Memphis blues guitar legend] Earl Banks, played in my daddy’s band, the Blue Dots, and Teenie joined them when he was 14, 15. While he was developing his skill, Willie Mitchell got a chance to hear about it.”

Along with Hi Records (which was co-owned by Willie Mitchell), Stax is the other great contributor to Memphis soul music.

“Teenie’s first playing was actually at the Stax studio with Isaac Hayes and David Porter,” Hodges explains. “They even wrote a few songs together, like ‘I Take What I Want.’ But Willie talked him into uniting with him at the Hi studio [Royal]. Under his tutelage, Teenie got even better because Willie had a sound and his own identity.” One of Mitchell’s suggestions to the 16-year-old Hodges was to ditch his thumb pick in favor of a flat pick.

“Teenie and Leroy were also playing in a really tight group called the Impalas that started to get fame,” Hodges continues. “Since Willie already was training Teenie, he decided to hire them both. I was traveling with the soul singer O.V. Wright, who told Willie that the fans would come out to the shows to see me as well as him. Willie’s piano player was often late, and one time he didn’t show up, so I was called to replace him.”

The band went through a grueling few years of touring. After experiencing a terrible van accident that almost killed them, they decided to shift their focus to recording, and so the Hi Rhythm Section was born, featuring Teenie, Charles, and Leroy Hodges, Archie “Hubbie” Turner on keyboards, and either Howard Grimes or Al Jackson Jr. on drums.

“That’s when our whole identity turned,” Hodges recalls. “If you listen to the records, you can see the change in the music. Teenie was the one Willie used to get the Al Green songs together, while O.V. Wright and his material was turned over to me.”

The Hi Rhythm Section’s musical communication during the sessions was pretty much telepathic. Maybe not surprising, since three of them were brothers. Turner had grown up in Willie Mitchell’s house as a teen, and they had all played together in other bands.

“The guitar player knew what the organ player was going to do, and the organ player knew what the bass player was going to do,” Hodges says. “We all knew what everybody was going to do.” With his impeccable sense of time, Teenie Hodges became the leader of the group.

“Teenie was the one who would put a song in the pocket,” Hodges says. “We would come up with the rhythm pattern and mood of it, but he was the master. You can hear the guitar on all the records. We would follow him. Once we heard something that he did and went ‘Amen, that’s it,’ we’d jump on that and get it to a perfection.”

Shore got a similar impression of Teenie during his film shoot. “There’s the famous story of how he counted off ‘Love and Happiness’ on the Coke crate [you can hear him stepping it out on the record]. No matter who was playing with him, it was his groove and it was always on his count.”

There are many moments on those classic records with Al Green, Ann Peebles, Syl Johnson, and the other Hi artists that sound improvised. For instance, the second half of “Love and Happiness.” Were they?

“Believe it or not, all of it was spontaneous,” Hodges says. “There was no such thing as rehearsing a song before we recorded it. Either Teenie, Hubbie, Leroy, or I would get around you and pick out the chords together, and then we’d figure out where the song is going and get a pattern together.

“When Al Green brought ‘Love and Happiness,’ Teenie had already picked it out because they were co-writers of the song. But when you get to the later, improvised part of the song, where Al goes, ‘Love can make you do wrong,’ that is all feel. This is what the person feels inside of them to do. Nobody can give you that. This is something that you do with your creator. He gives you the feel and the ear to hear it, and you have to improvise on what you are hearing.

“But if you heard us play it onstage, see, we would do something else. You have a confined position with your recording. You can only take it so far. Like writing a book, you can’t tell the whole story, but you’ve got to tell it well enough to make people interested in buying it.

“This is the same way with music: You can’t play everything that you feel and want to play; you’ve got to stay with the script. When you do it live, you can improvise more after you do the song. Because people are coming to hear the song, and when they’ve heard it, then you can let them hear you, your talent, and your abilities. And that’s the way we did it.”

One of Teenie’s personal guitar influences was Reggie Young, another late Memphis icon who played on Elvis Presley’s 1969 album From Elvis in Memphis, with the Highwaymen, and with many others.

He was also Willie Mitchell’s first guitar player. “If you asked Teenie who was the greatest guitar player, he said Reggie Young,” Mitchell reveals. “He got a lot of his style and inspiration from Reggie, and even named his first boy after him.”

In terms of gear, Hodges used a simple setup. Although he owned at least 50 different guitars, including a Telecaster and a Steinberger “headless” model that he favored in later years for its lightness (“My dad hated that guitar!” Mitchell says), the main guitar on the classic records is a 1970 or 1971 Gibson Les Paul “Black Beauty/Fretless Wonder” going through a blackface Princeton amp from the late ’60s. And if you want to get anywhere close to dialing in his guitar tone, you need to keep it clean and leave most of the pedals at home.

“Teenie taught me to embrace clean, sexy guitar tones as opposed to distortion,” Dickinson says. “He let the wood breathe and groove through the strings, pickups, and amps.” Mitchell doesn’t recall him using too many effects either. “Mostly it was straight into the amp,” he explains. “He played wah on a couple of early Al Green songs [from Al Green Gets Next to You].”

Not only did Hodges have a knack for coming up with the perfect guitar parts; he was also the co-writer of several iconic Al Green hits, including “Take Me to the River,” “Love and Happiness,” “L-O-V-E (Love),” “Oh Me, Oh My,” ”Full of Fire,” and “Here I Am (Come and Take Me).”

“He was really masterful at turning his life situations into songs,” Mitchell says. “I think ‘Take Me to the River’ was inspired by a pond that he was baptized in by a church in Germantown,” where he was born on November 16, 1945.

Adds Shore, “Usually, Al wrote the lyrics and Teenie wrote the music in their co-writes, but you can tell which lyrics are Teenie’s in ‘Take Me to the River.’ It’s the lines where he’s talking about real life stuff, while Al’s lines are more about God.”

The opening scene to the 1984 documentary Gospel According to Al Green provides some insights into how Teenie and Green worked out their songs and guitar parts. In it, Green is improvising a song called “I Love You,” singing and fingerpicking bluesy, soulful chord progressions with the pleasantly unexpected twists and turns that are a signature part of his songs.

Hodges saw many moments like this as Green and Teenie arranged songs and guitar parts, with Green on acoustic and Teenie playing electric.

He recalls that the singer was at first reluctant to play on his 1972 song “Simply Beautiful.” “Al could play, but he was shy,” Hodges says. “He didn’t think he could do it. After we had worked the song out, Teenie told him to play the acoustic part, but Al said, ‘No, man, I’m not gonna play no guitar on it.’ We insisted; he refused.

“Then Willie overheard us and said, ‘Hey, what’s going on out there?’ We said that Al has such a good feel on the guitar, but he doesn’t want to play it. After they were going back and forth, Al agreed to play, but said that he knew we weren’t going to like it and that he’d mess up. He cut it, and it was just perfect.

“They played real good together,” he continues, “and they co-wrote 13 of those Gold and Platinum songs. They’d get the structure of it and tell us how it was going to go, and we’d sit down and play it: Hubbie on keyboards, me on organ, Michael Allen on keyboards, James Brown on piano. Sometimes we used three keyboards.”

Teenie Hodges began to receive greater recognition in his later years. He continued to perform and play sessions, including on Cat Power’s critically acclaimed 2006 album, The Greatest. A reviewer from The Chicago Tribune wrote, “Teenie Hodges is the album’s secret weapon; his selfless style and stylishly understated riffs, fills, and chords underline and complement Marshall’s every move.”

In 2012, filmmaker Susanna Vapnek created a short documentary about him called Mabon “Teenie” Hodges, A Portrait of a Memphis Soul Original. Two years later, a couple of months after playing at the South by Southwest festival in Austin, he passed away from complications of emphysema at age 68. Luther Dickinson shared the stage with him at that final concert.

“Teenie and I sat together and chatted while we waited on Snoop Dogg to arrive,” he recalls. “He was in poor health but in high spirits. His playing reflected his health, and, as always, he played with the minimalism of a zen master. As we sat, he played his iconic guitar part to ‘Tired of Being Alone’ very slowly, as if to show me he still had it.

“All of a sudden, Snoop shows up, Boo Mitchell hands him the mic, he calls ‘Gin and Juice,’ counts off the band and whoa! As the final chorus kicked in to bring the song home, the most soulful blues lead guitar I had ever been in the presence of shot through my being. I thought, Who is that?, and sure enough, it was Teenie.

“He had been reserved all day until he let out an expression of a lifetime, rising to the moment and further levitating the music. Teenie showed us how to make the most of whatever you’re capable of in any musical scenario. As my father [studio legend Jim Dickinson] always said, ‘Play every note as if it were your last. Because one of them will be.’” ‘

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue

"Get off the stage!" The time Carlos Santana picked a fight with Kiss bassist Gene Simmons and caused one of the guitar world's strangest feuds