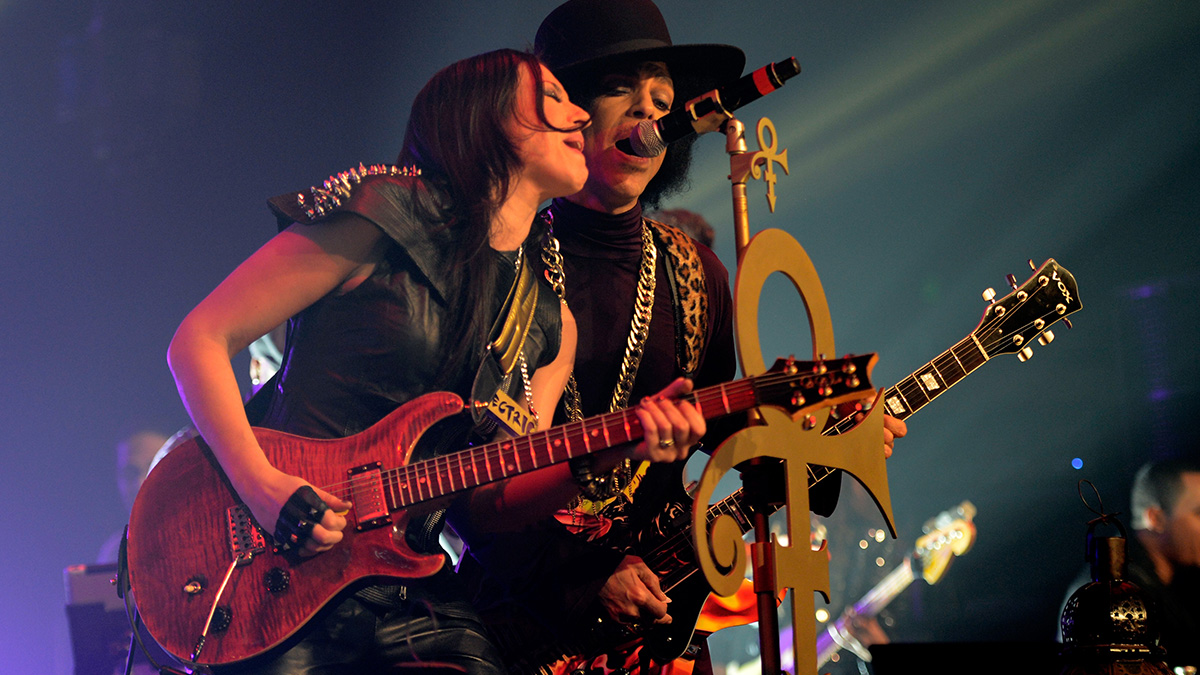

The Legend of Prince: The Purple One's Guitar Players Share Untold Secrets and Tales from the Studio and Road

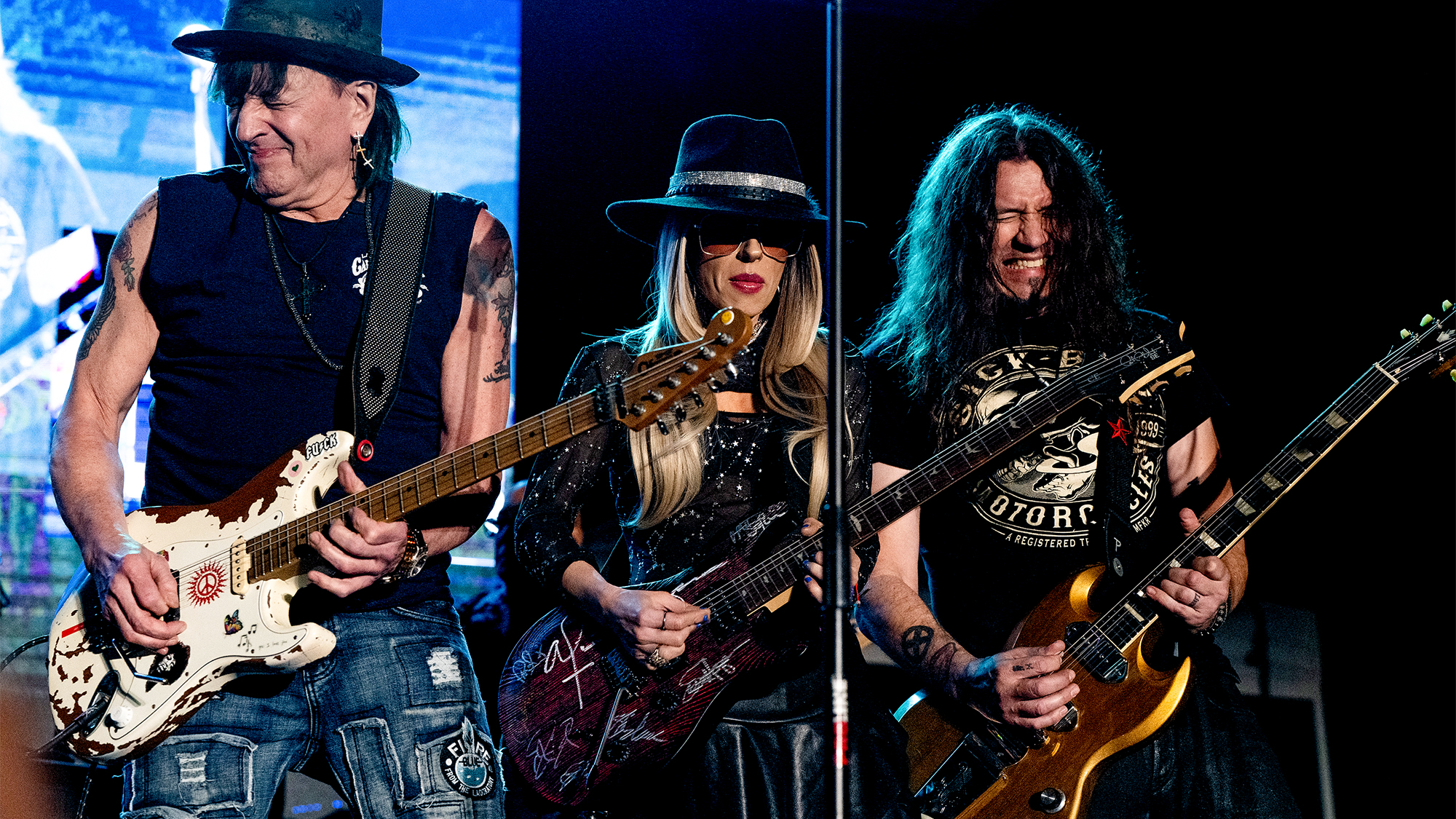

Mike Scott, Dez Dickerson, Donna Grantis, and Kat Dyson tell all in these GP-exclusive interviews.

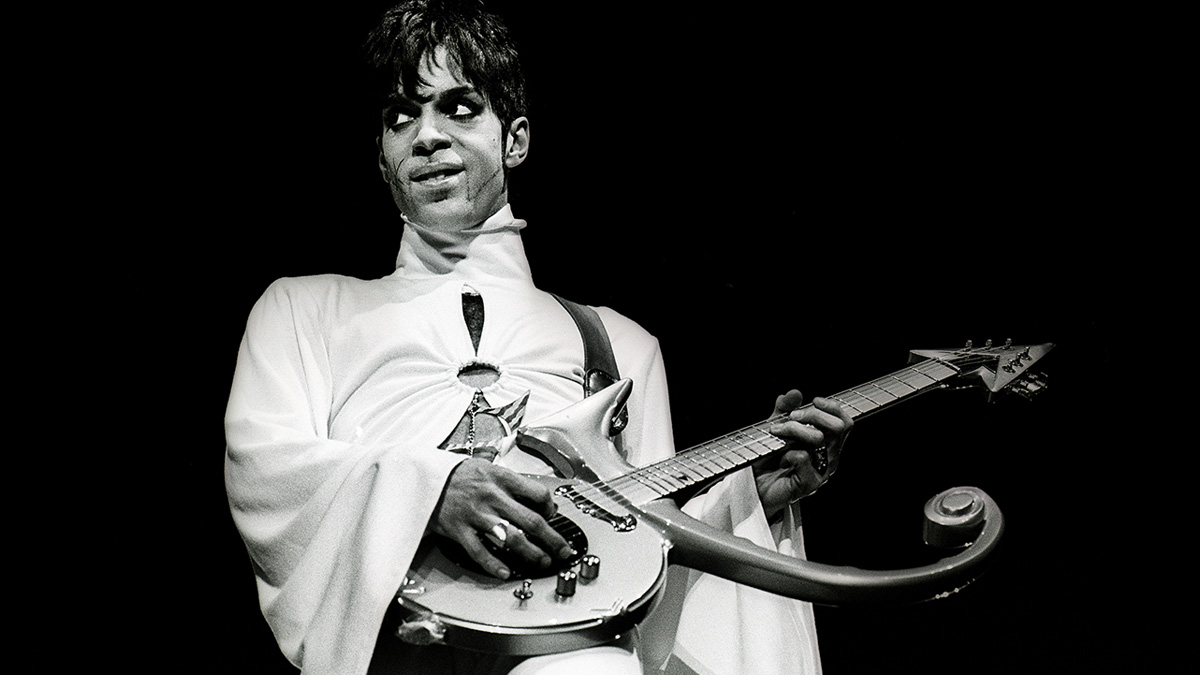

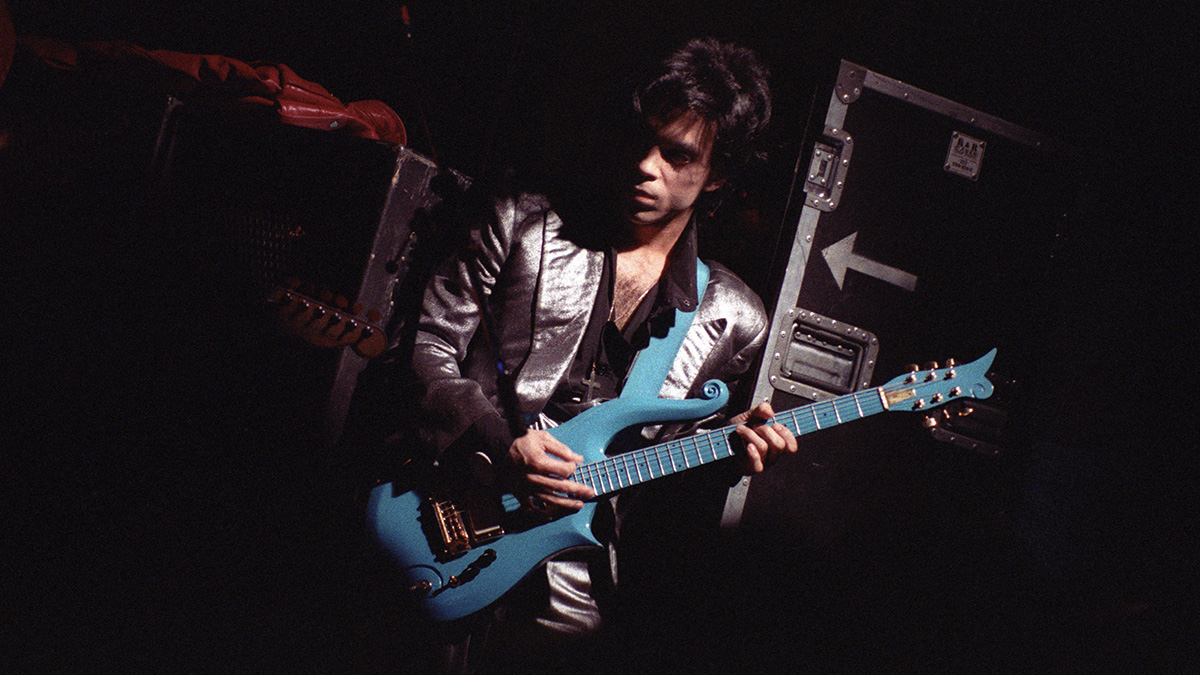

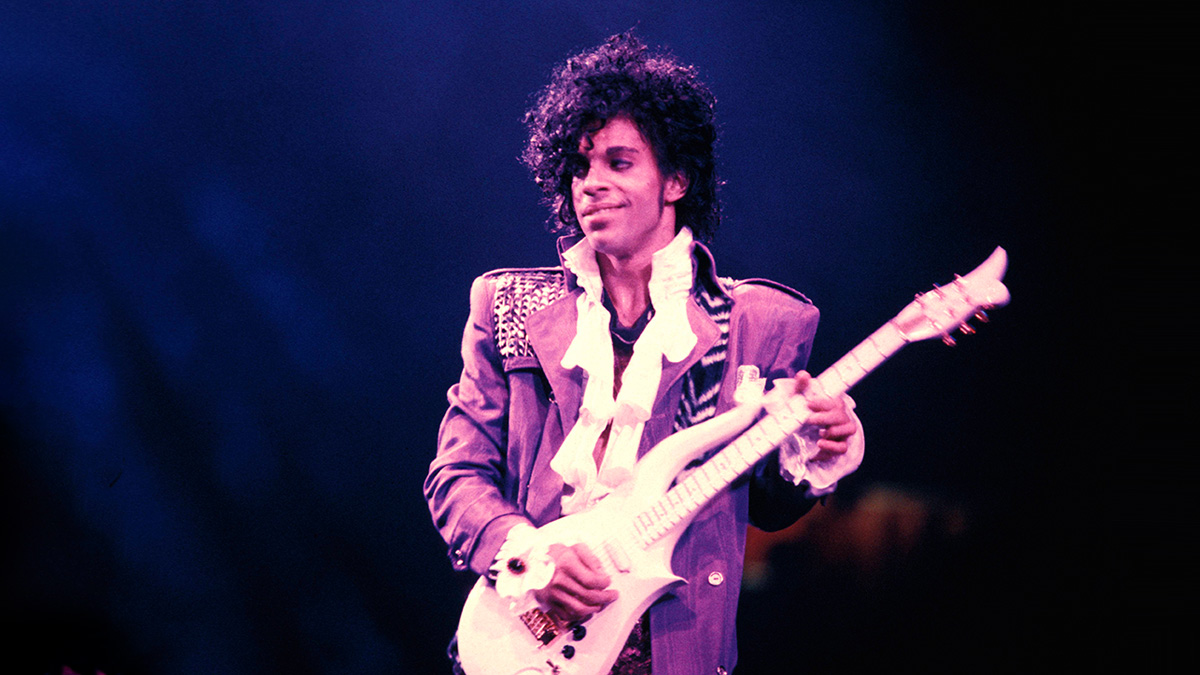

The phenomenal body of work Prince created during his 57 years on Earth testifies to his songwriting genius, his sheer musicality, and his awesome guitar skills. But Prince was unique in that he processed similarly high-level skills when it came to recording, producing, choreography… You name it.

Prince, who seemed born to become the high priest of pop/funk, drew the inevitable guitar and showmanship comparisons to Jimi Hendrix and James Brown, and he was certainly the funkiest dude around, even though he loved hard rock and psychedelic music and drew from influences wherever he found them.

His work ethic was unstoppable, and he drove those around him to rise to their utmost abilities, and then take it a notch further. The ultimate manifestation of his all-or-nothing approach to just about everything was, of course, Paisley Park, his Minneapolis-based headquarters, where he drilled his musicians relentlessly, recorded music practically nonstop, and basically inspired everyone to be all they could be.

If you were invited to be in Prince’s band – which in itself was a litmus test that hinged on one’s musical skills and creativity – it was implicit that you were signing on to work at the same grueling pace that Prince demanded of himself.

That included rehearsals that lasted for hours, mandatory choreography for the stage show, and then the studio sessions that all band members were on call for virtually any time of the day or night.

Those who felt like they had earned the right to play alongside Prince might have been surprised by the sort of boot-camp mentality that existed within Paisley’s confines, but with it came the lessons that Prince imparted to his players – lessons unavailable anywhere else – and the payoff for being brought into his world was a high-paying gig that practically guaranteed a musician would leave the band a better musician when the time came to move on.

Mike Scott

“He single-handedly helped me become the guitar player that I am today,” says Mike Scott, a blazingly skilled guitarist who had worked with the rap/R&B duo Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis (among many others) before joining Prince in 1996.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Scott toured extensively with New Power Generation and contributed to the albums Emancipation, Crystal Ball, The Truth, and Newpower Soul.

“As far as a lead player, I was a little more technical than Prince was because I was listening to Return to Forever, Al Di Meola, the Mahavishnu Orchestra, and stuff like that,” Scott says. “But when I would take solos with him onstage, he was like, ‘Man, all those notes don’t mean nothing because they don’t translate in an arena. I’ll hold a high note and have people screaming while you play 100 notes, and nobody’s going to hear what you did.’

“That was one of the most important things he ever told me, and there were so many moments like that, and so many things he shared that made me a much better player.

"Prince was a great guitarist and he was a showman – he knew how to bring a crowd to their knees – so I would color outside the lines. I would take solos that had more theory behind them as opposed to just doing crazy pentatonic stuff like he’d been doing forever.”

How did you two work out what tones you would use for certain songs?

One day he called me out because I had taken a distortion solo. He said, “Hey, Mike, I just did a fast song and I took a distortion solo. What do you think I should use: distortion or clean?” And I said, “Well, if you just used distortion in the first solo, then I would go clean."

And he goes, “That’s right. Don’t ever step on a distortion pedal after I’ve taken a solo. If I take a distortion solo, you take a clean solo." So for the rest of the tour, distortion was bad.

But one night, an opportunity came up during the “Purple Rain” chorus. He steps on his distortion pedal and he had nothing – his rig was out. So he points at me and shouts, “Take a solo,” and I got to rip the shit out of that “Purple Rain” solo once in the whole time I was with him. At the end of the night, he said, “Did you enjoy that? You’ll never get to take that solo again!” [laughs]

Did Prince want you to play certain guitars?

He had me playing hollowbody guitars a lot. I was playing a PRS Hollowbody II Piezo the last time I was with him, and he told me, “I love that Hollowbody sound, and I love that you can go to acoustic.” I run the magnetic and piezo pickups at the same time, and I blend them.

I run a Dunlop Rotovibe on the clean Hollowbody sound, and I put the acoustic pickup straight through a Fishman or a Hughes & Kettner acoustic amp, and it’s an amazing wall of guitar. One of the last times I was out with him, Prince wanted me to play the same guitar he was playing, a Vox HDC-77.

I don’t know if he thought I was going to be mad about it, but any advice he gave me, I would jump right on it. So I called Vox that same evening and had them send me two HDC-77s.

That guitar is badass. It does single-coil, humbucker, and P-90 in the same pickup. It’s a very versatile guitar. It can sound very Strat- or Tele-like, and the humbucker is just balls to the wall. So I understood why he was playing that guitar. I started playing one, and I still do.

What are some things you did that you know impressed him?

Sometimes he’d play something and say, “Do a harmony to this.” And it would blow his mind because I never had to practice that stuff. There’s a live video of us playing in London, and he broke the band down and just had me play by myself, and I was playing this guitar part that was a combination of my part and his part – and then he changed keys and I was still doing it in two-part harmony. That impressed him.

When I started working with him in ’96, he had a studio tech named Hans Buff, and when I would go in and record, Hans would later tell me, “Man, Prince raves about you. He solos your parts out and he loses his mind.” But I never saw any of that.

I thought Prince hated my playing because he would always ride me and give me shit. But one day, he and I went for a limo ride to an after-show party, and we rode around town trying find a club to go to.

That was the first time he and I talked just one on one. And he said, “Mike, you’re a great player and a great musician. If you started believing in that, you would take over the world.” That was the only time he gave me any kudos.

Did you ever have anything unusual happen on the road with him?

His rig blew up one night in London, just as he was pulling up in his limo, and it was because we were on British power and everything was on convertors. He had a buzz, and his tech, Takumi, was trying to get the buzz out, and his whole rig just went up in flames.

He and I were both using four-foot racks at that time, and he had a Soldano SLO preamp with the auto faders, and that thing breathes fire. His lead tone was amazing, and he wasn’t using pedals. So his stuff went up in smoke, and he’s now in the back of the venue asking why he can’t come up and play. And we were panicking!

I said, “Look, he only plays on the first song, so plug him into my rig and set me up with a Fender Twin, and then after the first song you all can figure it out while we’re playing.” So they plug him into my wireless system, and he comes up to the stage and grabs his guitar – and when Prince comes in a room, he’s ready to play!

He walked right onstage and we started jamming, and he walks over to me and says, “My guitar sounds amazing tonight.” [laughs] He never knew he was playing through my rig, and I never told him.

Were you expected to own a part the minute Prince showed it to you? Did he have any advice for memorizing parts?

Yeah, he would show you something once, and he would not show you again. And he would know if you didn’t play it exactly right. Sometimes he would show us stuff and we wouldn’t remember it the next day.

Like, you wouldn’t remember this rhythm pattern that was bouncing off of the keyboard pattern that was bouncing off of the bass pattern. So he told the band to start taking ginkgo biloba [a tree species known to enhance brain function], because it’s great for your memory.

I started taking ginkgo, and it helped immensely. Prince would push you to the limits. Like, if you came in today for a rehearsal, he’d go, “I’ve got a new song,” and we’d learn it. But we probably wouldn’t play it for six months, and he would still expect us to play it just like you learned it today.

Prince docked the whole band once, because he went to the bridge too early and we didn’t follow him. He said, “I never make mistakes – you all made a mistake by not following me.” So we all got fined

Mike Scott

So besides all the drinking and ridiculousness going on on the tour bus, I would sit and go through his whole repertoire before the show, because you never knew what songs he was going to call, or even what the set list was going to be each night.

That made it a challenge and made you have to step up your game, because everything you did had to be on point. And if you made a mistake, he would look at you and rub his fingers together, and that meant you got docked.

One time he fined me $1,000. I said, “You’ll never fine me again,” and he never did. Although he did dock the whole band once, because he went to the bridge too early and we didn’t follow him. He said, “I never make mistakes – you all made a mistake by not following me.” So we all got fined.

That’s an old-school way of running a band, like James Brown or something.

It doesn’t happen anymore, because a lot of these shows have tracks playing in Pro Tools. I started playing with Justin Timberlake in 2008, and his show was based on choreography and lights, and nothing can change. It’s the same show every night. With Prince, it was always a crap shoot.

He used to say, “Real music played by real musicians.” We may have played over a drum loop occasionally, but I don’t think we ever played to Pro Tools. Prince was a learning experience, and God only made one of him. He was an amazing teacher and an amazing mentor. You definitely would leave there a better musician than you were when you came in.

Dez Dickerson

Dez Dickerson’s rocket ride with Prince started when he answered a call for a touring musician in The Twin Cities Reader, a Minneapolis entertainment paper, in 1979. After a 15-minute audition behind a tire shop, he was chosen as guitarist for the group that would become Prince and the Revolution.

Dickerson played the slinky guitar solo on “Little Red Corvette” and contributed vocals to it and the title track on the 1999 album. He appeared in the film Purple Rain, and wrote songs for Prince’s side projects. His credits include writing “He’s So Dull” by Vanity 6, and co-writing “Wild and Loose,” “After Hi School,” and “Cool” for the Time.

What did Prince initially dig about your guitar playing?

I was a Grand Funk Railroad fan, and that band influenced me more than anyone else. That whole power-trio, “the guitar is king” aspect of it is something that Prince loved, and he found ways to incorporate it. There were Hendrix influences and Carlos Santana influences, but there was other stuff too, and Prince always found ways to marry it with the groove, because that is who he was.

The first five Prince albums seemed to evolve in quantum leaps. How did that happen?

Yes, it was a quantum leap from For You to 1999, and for the most part there was a practical process that expedited that development.

One of the things that had a major impact was that, once the band was formed and we did the first couple of tours, Prince continued as he had from the beginning, where he went in and composed, performed, produced, and recorded on his own. So the second record was a continuation of the first one in that sense.

But the thing that changed is that, as we grew and kind of coalesced as an actual band, the rehearsing part – and I mean, like, six- to eight-hour rehearsals and jamming – began to have an impact on how he approached his process.

So he started to see himself more as a band guy than a solo artist?

One of the things he was very adamant about was us being a band, so over time he kind of absorbed and re-imagined his process. As we got into the later things, like Dirty Mind and Controversy, and definitely by the time we got to 1999, in terms of what he and I did, he made space for me as a guitar player and this other set of influences and whatever else I brought. He made that part of what Prince and the Revolution became.

How did he develop his ideas?

A lot of those things developed in jams and rehearsals and sound checks and the tour bus. In the studio, he was always the guy that would go in with ideas and then iterate those ideas. But when he got to the point of Dirty Mind and onward, he always had his own studio, and that empowered him to do whatever he wanted to do.

One of the most important developments in Prince’s career was when he signed that initial recording contract, and his manager and attorney at the time negotiated a deal with Warner that was pretty impressive in that it gave him the unrestricted power to do what he wanted.

So once the technology was in his hands and he didn’t have to go in the studio with an engineer and the songs, it just became a continuous process, and it remained that way.

Recording and creating was just what Prince did 24/7, and the songs reflected that. They would change in rehearsals and at sound check when we were touring. And they kept growing and changing.

Did you and Prince talk much about guitars and gear?

As he began to define what the elements of his sound were, there was a point on one of the tours when he asked me to play a Telecaster, because he had those Hohner [MadCat] Teles that he loved. There was a unique sound to those inexpensive guitars that became what you recognized as his sound. So for a couple of tours we had sort of duplicate rigs.

He was playing through a Mesa/Boogie, and even though I had been using Marshalls to that point, I started playing through a Mesa/Boogie. But then it kind of morphed back. Prince said, “I’m going to let you do what you do, and I’m going to do what I do,” and he made space for the thing that I was bringing to it.

Prince wasn’t a gearhead who talked about pickups and string gauges. It was more a matter of the sound

Dez Dickerson

We had a conversation after a show one night, and he said, “I’m going to start focusing on being more of the entertainer and the frontman, and I’m not going to play guitar – I’m going to leave more of that to you.”

But Prince wasn’t a gearhead who talked about pickups and string gauges. It was more a matter of the sound, and to his credit he gave me the space to be who I was and do what I did with the gear that I loved using. Prince knew what he liked and what got the sounds he wanted, so it wasn’t like he had a huge pedalboard – it was just certain things.

There were Boss pedals that he liked, and that was what he used. And once he moved to the Mesa amps, that was it, because the clean tone was exactly what he wanted when he played the Hohner Tele through it. When Prince found what he wanted, he stuck with it. Although, after I left the band, he experimented more with other gear and other sounds.

How did the Linn Drum impact Prince’s sound?

He had one of the first ones off the line, and it instantly changed everything. He basically began to program single grooves and loop them and write around them, so there was a point in time – and obviously the 1999 album was the tipping point – where the Linn Drum became part of the sound.

It wasn’t at all surprising that he pulled it out of mothballs later and kind of went back to it. It’s like somebody pulling out a guitar they used to play and coming back out with it.

The Linn Drum had been a huge part of his process during that early period in time, and he basically used it as another voice in the music. So bringing it back made all the sense in the world to him.

How did it affect the live shows?

Prince was a fanatic about the pocket, and the Linn Drum created the perfect storm, where it played what you told it to play and would play it endlessly and not get tired and not talk back. So it was an important tool.

When that era began, everything from that point forward was about playing to the click, because the Linn Drum demanded to be followed. Prince was a really good drummer himself, so he knew what he wanted the drummer to play, and once it was on record, that’s what it was going to be. He could modify and change things, but the drums were kind of non-negotiable.

Kat Dyson

Guitarist Kat Dyson had expected to be auditioning for Sheila E. when Prince intervened and snapped-up the Montreal-based player for his own band, the New Power Generation.

Dyson performed with Prince from 1996 to 1998 (rejoining again in 2005), and her spectacular guitar work graced the albums Emancipation, The Truth, and Newpower Soul.

Highlighting her versatility across a wide range of styles, Dyson has also worked with a cast of renowned artists, including Cyndi Lauper, Natalie Cole, Sheila E., Ivan Neville, Donny Osmond, rap artist T.I., Seal, Joi, and George Clinton and the P-Funk All Stars.

When I was standing next to him at a rehearsal, he would just play something once and say, “Got it?”

Kat Dyson

How did Prince communicate his guitar ideas to you?

When I was standing next to him at a rehearsal, he would just play something once and say, “Got it?” And then he would go sit on piano and expect me to play it perfectly. But he knew that my ear was acute, and that I was a listener who knew a few things about him.

Everybody plays guitar differently, because of the size of their hands and the width of their fingers, and all that. So my experiences with Prince did bring me forward in the sum total of my technical knowledge and the way he expanded it, because of how he played and what he used to get the sounds he felt comfortable with.

Do you remember your first live performance with Prince?

The first thing I did was Late Night With David Letterman, which I think was one of the last obligations he had with Warner. We did a song called “Dinner With Delores,” and I played guitar and he played piano. So I played his parts and I played his solo, which was kind of a line-harmony thing he did with [horn player] Eric Leeds.

I remember having to make my way back to Canada to do something for Canada Day, so I missed one of the TV show gigs, but the next one I made, and then we went back into rehearsals and worked on the show for months.

What can you tell us about your studio work at Paisley Park?

Well, other people know what I played more than me, because it was a constantly revolving thing. There was never any, “Okay, today is a studio day.” It was just, “Let’s go in. Let’s stop here.”

We recorded just as Prince thought of it, and everybody was on call for everything all the time. I remember, we were messing around once in a rehearsal, and I was playing something on acoustic guitar, and the next thing I know, I’m in the studio. He says, “I like that pattern you’re playing. Can you put it on this song?”

I’m of the opinion that Prince was recording our rehearsals all the time – even the breaks when we were just noodling around – and there was something going on where he could hear what we were doing

And it turned into “Dreamin’ About U” [from Emancipation]. It was me just practicing something on acoustic guitar to stretch my hands out. Sometimes we would rehearse 10 to 15 or more hours a day, and the nylon-string Godin was good for stretching my fingers on.

But Prince was always recording, although he didn’t need me a lot, because he’s a guitarist. One time, he called me in to put something on the song “The Love We Make.” He had already done it as vocals and piano, and he said, “I like the way you voice that particular chord. Can you use that voicing on this?” But I would never know if it would make the cut as far as what he dug.

I’m not completely sure, but I’m of the opinion that Prince was recording our rehearsals all the time – even the breaks when we were just noodling around – and there was something going on where he could hear what we were doing, even if he might not actually be there and we were just running through stuff with the guys. At Paisley, everything was live, and he could hear everything that was going on in all places.

Did you discuss gear with him very much?

Not really. When I first came there, he told me what he did not want us to play, and that was Fenders or Gibsons. I don’t know what all that was about, because later he started playing them. I guess he had some situation, because he’d say, “They all want you to do something for nothing.”

At the time, Prince had a lot of rack stuff, and I was using a Rocktron Taboo Twin combo. It was programmable, but it looked very simple. I’d had all the Rocktron Intellifex stuff, so this was like taking the best parts of what they had and putting it into something small.

Prince would look at my amp and then look at all his stuff, and he’d say to his tech, “Why can’t I get that sound?” But I knew my gear, and I was already into sound modeling and pulling up tones, just learning on my own.

I used my ears to shape whatever technical knowledge I could get, and I was always bugging amp makers and talking to people when I went to NAMM. I’m curious, so that’s what I do. Prince would just say, “Go to NAMM and find something cool, and tell me about it!”

Did he ever express interest in any of the guitars you played?

Not directly, but at the time I had a nylon-string Godin Multiac, which was a great guitar that had MIDI capabilities. He got a big kick out of that. I would mess around with altered tunings, because I’m a big fan of Joni Mitchell, and I would often leave the guitar on a stand when I left for the night.

But when I would come back, it would be tuned standard, and I was always telling the tech not to retune it. One time, I got a call at three in the morning, and it was Prince’s tech, and he asked if I had my guitar. I said, “Yeah, did somebody break into Paisley?” He said, “No, but can I come over and get it?”

I asked what for, and he said, “Well, Prince has been using it when you’re gone.” [laughs] So I asked Godin to send Prince a Multiac. But he still had trepidations and said, “Really, what do I have to do?” I told him to just play it: “I want to be able to take my guitar, so this is my gift to you!”

Donna Grantis

After receiving an invitation to come to Paisley Park in 2012 to audition, Canadian session and touring guitarist Donna Grantis jammed a short list of tunes with Prince, bassist Ida Nielsen, and drummer Hannah Welton for a project that would become the funk-rock trio 3rdEyegirl.

After touring in the U.S., Europe, and U.K., Prince & 3rdEyeGirl released Plectrumelectrum. From 2013 until Prince’s death in 2016, Grantis remained a member of his supergroup, the New Power Generation.

What are some of the most important things you learned from working with Prince?

I learned a lot from him about funk guitar playing. I’d watch and listen intently as he demonstrated funk riffs he wanted me to play. I compiled those musical gems into a score titled “Funklopedia” for reference and personal study.

In addition to expanding my vocabulary in the genre, I learned a lot about funk phrasing from Prince, in particular, how he approached playing certain parts of a phrase in an extremely staccato manner. He taught me to approach those notes as if they had “no value” rhythmically. This, along with impeccable timing, tone, and articulation contributes to how a musical idea can sound truly funky.

Did the experience affect your equipment choices?

Performing an expanding repertoire of funk-infused music with New Power Generation definitely impacted my gear choices. Instead of rocking my PRS CE22 through custom-modded Traynor Bass Master amps from the ’70s, as I did with 3rdEyeGirl, I switched to using a PRS Mira Semi-Hollow through PRS Archon amps.

Prince liked the percussive quality of semihollow guitars for funk, and I love the playability of a PRS neck, so the Mira was a perfect fit. In contrast to the fat, dark, vintage tone with buttery sustain that I enjoyed in 3rdEyeGirl, I needed a super crystal-clear clean tone to best complement our expanding repertoire of Prince hits.

My pedals could shape the tone when needed, but most importantly, the clean tone had to sparkle. I dialed this in with the Archon by cranking the clean channel volume and adjusting the master volume to taste.

What were some of the highlights of recording Plectrumelectrum, and how did the experience impact your following solo release, Diamonds & Dynamite?

It was an amazing experience. Prince, bassist Ida Nielsen, drummer Hannah Welton, and I were set up in a dance/choreography studio that also doubled as a basketball court in Paisley Park, with mics running to Studio A, where our performances were captured live to tape.

We rehearsed there, performed for friends, and recorded most of the album in that room. Some songs, like the title track, were recorded in one take. During the recording of “Whitecaps” and “Anotherlove,” I remember Prince saying, “Call me when you have it!” and he left Hannah, Ida, and I to record as a rhythm section while he played ping-pong.

We worked fast – I don’t think we even played “Wow” all the way through a single time before the tape was rolling

Donna Grantis

Sometimes we jammed on a groove, like the one in “Stopthistrain,” and then discovered days later that it had been arranged into a structured song. We worked fast – I don’t think we even played “Wow” all the way through a single time before the tape was rolling.

This approach influenced how I produced my 2019 release, Diamonds & Dynamite. I recorded the album live to tape over two days in an effort to capture the authenticity and spirit of creative first instincts, a process I grew to appreciate during sessions with Prince.

I value the challenge of striving for a collectively moving performance and the outcome created when a group of musicians freely interact in the moment. There’s something very human and fearless behind that intent that I think translates musically in a special way.

Art Thompson is Senior Editor of Guitar Player magazine. He has authored stories with numerous guitar greats including B.B. King, Prince and Scotty Moore and interviewed gear innovators such as Paul Reed Smith, Randall Smith and Gary Kramer. He also wrote the first book on vintage effects pedals, Stompbox. Art's busy performance schedule with three stylistically diverse groups provides ample opportunity to test-drive new guitars, amps and effects, many of which are featured in the pages of GP.