The Incredible Story of Les Paul's "Lover" – the Breakthrough Multitrack Recording That Changed the World, Part 1

In 1948, Les Paul turned the recording industry on its head with “Lover” and its “space-age” guitars

***CLICK HERE TO READ PART 2***

A transformational moment in music history occurred 75 years ago in February 1948, when Capitol Records issued a 78 rpm record.

It was “Lover,” the first multitrack popular music recording created by superimposing discrete audio tracks. The vision, intellect and grit which this disc-to-disc undertaking entailed belonged to guitarist Les Paul.

The legend “The New Sound” appeared on the record label, heralding an era of new recording possibilities. From this singular achievement, the act of making records would become an infinitely more creative process through the advent of overdubbing.

The act of making records would become an infinitely more creative process through the advent of overdubbing

Among Les’s many accolades are inductions into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for creating the solidbody electric guitar and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame for his hit platters and leading-edge innovations. Indeed, Les is the father of modern sound, from whom some of music’s greatest recorded milestones and guitar players have sprung these past 75 years.

Les was 32 when “Lover” was released. He’d barely scratched the surface of what he would accomplish and be celebrated for. He was born Lester William Polsfuss in 1915 and grew up in America’s heartland, in Waukesha, Wisconsin, playing harmonica and piano before switching to guitar.

Drawing inspiration from Eddie Lang, Django Reinhardt and Andrés Segovia, he gained prominence in the late 1930s as a jazz and country artist and top session sideman. In September 1945, after serving with the Armed Forces Radio Network, Les, accompanied by his trio, waxed a postwar million-seller, “It’s Been a Long, Long Time,” billed with singer Bing Crosby. It was the first of his many hits.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The Rail, Log and “Klunkers”

But it was the single “Lover” and its success that fulfilled Les’s calling. His roles as musician, engineer and inventor merged on the recording, making him a latter-day wizard. The recording represented his coming of age, the culmination of years-long experimentation with electronic sound and recording.

At 13, he had amplified his acoustic guitar using a phonograph cartridge and needle wired to a radio for amplification. For him, the manipulation of sound would grow to become an obsession.

“Les would say, ‘You could be wrong a million times. You only have to be right once,’” recalls Michael Braunstein, executive director of the Les Paul Foundation. Braunstein became Les’s manager after his grandfather and father served in that role, and in 1995 he helped Les form the Les Paul Foundation to further music innovation through grants to educational organizations and institutions.

As Braunstein explains, Les devised multitrack recording in the early 1930s, while in Chicago, using a two-armed record cutter of his own invention that allowed him to cut a new track onto a disc while simultaneously listening to a track he’d previously recorded on the same platter.

“He built cutting lathes with a paring knife and a belt from a dental drill, and used them to first record his rhythm guitar,” Braunstein says. “He then used the second arm – the playback arm – to listen to what he’d recorded while he cut the record a second time.”

The technique was primitive and produced less-than-satisfactory results. “But it was the beginning,” Braunstein says. “It took years to develop that technique.” In the meantime, Les continued his attempts to amplify his guitar. He was unhappy that his phonograph pickup reproduced the sound of the guitar’s vibrating body.

He wanted the sound to only come from the string. That’s where the solidbody came in

Michael Braunstein

“He wanted the sound to only come from the string,” Braunstein explains. “That’s where the solidbody came in.” Les’s experiments in this regard involved a short length of steel railroad rail onto which he mounted a string and a telephone pickup wired to a radio. The Rail, as it was known, led him to build the Log using a four-by-four length of solid pine. It was the first solidbody electric guitar.

Les would eventually saw an Epiphone guitar body in half and attach these to either side of the Log. But as Steve Rosenthal, the Foundation’s archivist, emphasizes, the wings were purely for aesthetics, to make the contraption look like a guitar.

“Les didn’t want to hear the resonant frequencies created by the hollow body; he only wanted to hear the strings being amplified through the pickup,” Rosenthal says. “He ensured that by designing for the Log two wings that didn’t resonate.”

Les’s arsenal of home-built guitars eventually expanded to include three “Klunkers,” Epiphones modified with an access door in the back through which he could reposition the pickup. “He could move the pickup to find where it produced the best sound.”

In the Beginning Was the Disc

Equipped with his guitars, in 1947 Les applied his command of recording technology to make a record. At Crosby’s urging, Les had refurbished his garage into a recording lab, a precursor of the modern home studio.

By now he had abandoned his two-pickup record-cutting machine as impractical. Instead, he employed two record-cutting lathes: After cutting a disc on the first, he would play it back while adding a new part and record both simultaneously to a disc on the second record-cutting machine, then repeat as necessary to create a complete arrangement.

It was the advent of sound on sound, and more. Through his experiments, Les figured out that he could slow the lathe to cut the disc at half speed and make any guitar part he recorded sound twice as fast, and an octave higher, when played back at normal speed. Les called it his “space-age” guitar.

Likewise, he could record at a higher speed to make his guitar sound lower, like a bass, upon playback. In short, he could be his own one-man combo.

The song he chose to record from a bucket of 20 was Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart’s “Lover.” Perhaps Les, known for his sly humor, selected this composition for a line in Hart’s lyric: “In my ear you breathe a flame.” Les’s electrifying sound-on-sound instrumental would do just that.

As Rosenthal explains, it was the start of a technological firestorm: “You can look at ‘Lover’ as the start of the sound-on-sound revolution.” The media for Les’s disc-to-disc recordings were blank 16-inch acetate discs.

“Les used over 500 discs to create ‘Lover,’” Rosenthal reveals. Just a few years before, such luxury would have been impossible. In 1942, the War Production Board began rationing shellac – the main component in phonograph records at that time – due to the war effort.

“Fortunately for Les, after the war’s shellac embargo ended, he had an unlimited supply,” the archivist notes. “There are probably 30 or 40 arrangement discs that we’ve digitized for ‘Lover.’”

Audio Layer Cake

Rosenthal also details the order in which Les would meticulously build his recordings. “He would lay his first basic track on a disc,” he explains. “That could sometimes have been a snare drum, rhythm instrument or acoustic guitar track. He would then play along to it and create a second disc.

“Remember: There was no punching in, no dropping-in in 1947; if he screwed up, he had to throw out that disc and start over again. He would do that until he was satisfied. Then he took that newly created second disc, which would have parts one and two on it, and move that to the first turntable. He might say, ‘What we need now is a half-speed guitar.’ He would then work on overdubbing that guitar and add as many layers as he felt were necessary to complete the arrangement.”

As Les’s manager in the 1990s, Braunstein was an eyewitness to his perfectionism onstage, at the Iridium nightclub in New York City, where Les performed weekly for 15 years starting in 1995.

There was no punching in, no dropping-in in 1947; if he screwed up, he had to throw out that disc and start over again

Steve Rosenthal

“Les’s first Iridium show was at eight o’clock,” Braunstein says. “But he’d arrive at three o’clock. He wanted the soundboard to be perfect and would rehearse with the engineers until they got it sounding exactly as Les wanted. You couldn’t keep up with him. Doing what he did would have driven most people mad.”

Rosenthal delineates how “Lover” showcases this precision. “Les recorded the rhythm guitar part with a snare drum, or sometimes a tambourine with a metronome, to keep him in time. Les once remarked, ‘Instead of a metronome, I would often keep time by beating on the guitar’s neck and strings, then lay a rhythm track.’

“There are also times where he, or his wife, Mary Ford, strummed a straight rhythm, which set the tempo upon which they would build the arrangement. In the case of ‘Lover,’ I found a stem where he played a snare drum along with a rhythm guitar.”

Rosenthal adds that there are many instances where Les played the bass part on his guitar’s low strings, recorded at double speed. “On the record’s final version, it dropped an octave because he played it back at regular speed. We hear this on many stem arrangements.”

“Lover” is comprised of two sections, which Les worked on separately. Section one features guitar at regular speed overlaid with the “space-age” lead guitar, recorded at half speed to sound an octave higher on playback.

“For the second part, he edited a separate double-speed section,” Rosenthal explains. “Sometimes he would layer the ‘space-age’ guitar two or three times, all while ensuring the consistent clarity of each track and meeting the challenges of distortion and noise.”

There were lots of parts, but Les could think more than three steps ahead. His head was already at the end of the recording

Michael Braunstein

Indeed, with disc-to-disc recording, each subsequent generation resulted in a loss of fidelity for previously recorded tracks, along with an increase in the noise floor.

“Les understood that before every subsequent track or layer the first track that gets laid down gets a little distorted,” Braunstein says. “He had to arrange in his head the least important aspects of the song, which he would then put down first, and the most important aspects of the song, which he would put down last because they would need to have the best fidelity.

“He’d say, ‘Okay, this will get a little lost, but it’s not as important as the next part.’ There were lots of parts, but Les could think more than three steps ahead. His head was already at the end of the recording, thinking, ‘My lead guitar is the voice and has to be crystal clear. So that’ll come in last, especially my half-speed ‘space-age’ guitar, and I’ll have to put everything else first.’ He used the same technique when recording Mary Ford’s vocals.”

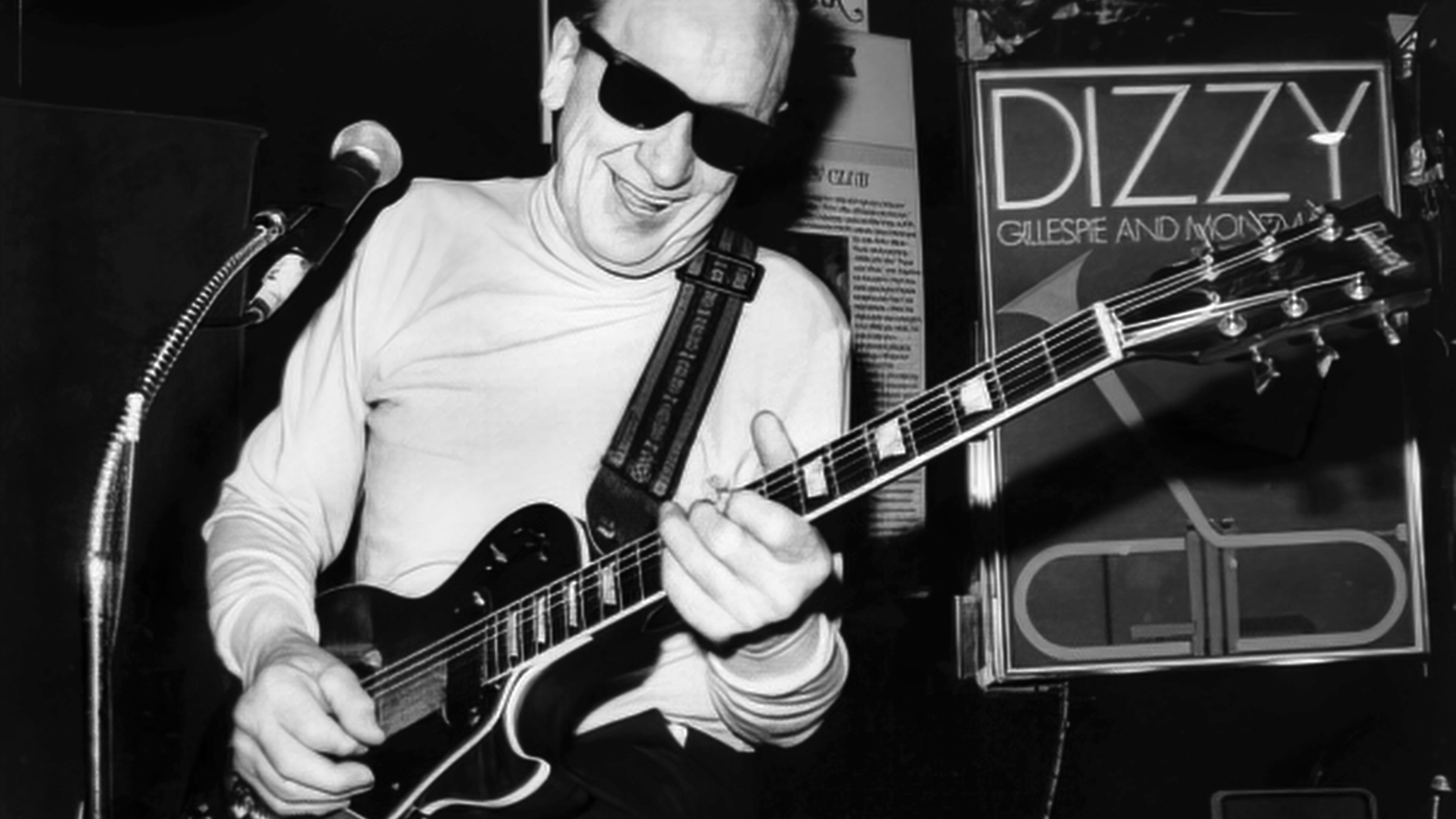

Les Thru the Lens

The Les Paul Foundation is honoring its namesake with the exhibition Les Paul Thru the Lens, a traveling gallery of rare photos that chronicle the life and career of the inventor, musician and icon.

The Foundation has granted Guitar Player exclusive access to these treasures, as seen on these pages.

Following a display at Memphis’ Stax Museum of American Soul Music, the Foundation is arranging the 2023 schedule, which touts an added element.

“[American artist] LeRoy Nieman once visited Les at the Iridium and sketched him in different poses,” says Michael Braunstein, the Foundation’s executive director.

“The plan is to include those in the exhibit adding another chance to see how Les influenced people from all walks of life.”

Venues interested in hosting the exhibition may email caroline@m2mpr.com.