The Guitarists of David Bowie: Carlos Alamar, Adrian Belew, Reeves Gabrels, Nile Rodgers and More Share Their Memories

The inside story on David Bowie's star-studded procession of guitarists, by those who were there.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

David Bowie’s death from liver cancer on January 10, 2016 - just two short days after his 69th birthday - was a shock and a blow to the world’s music lovers.

But perhaps missed by much of the culture at large was how epic his influence was on the guitar. Bowie worked with some of rock’s most transcendent guitarists, and he gave them the space to expand their techniques, tones, and creative concepts through his music - all while maintaining their individual imprints and approaches. A stylistic chameleon of the highest order, Bowie also gave us an opportunity to hear the guitar raging unfettered in a number of musical genres, from experimental to pop, new wave to industrial, R&B to funk, and beyond.

Getting the guitar story behind all of Bowie’s artistic shifts and evolutions was a rather significant undertaking, and we can’t offer enough appreciation and thanks to the guitarists who shared their memories of recording sessions, live shows, signal paths and gear, production concepts, songwriting, and more - even as they were grieving over losing a friend, peer, collaborator, and/or mentor, and were already being barraged by the mass media. I was so grateful to reach so many Bowie guitarists and superstar producers Tony Visconti and Nile Rodgers, while Michael Ross was able to talk to David Torn, as well as get a little more “Bowie info” from Ben Monder, who he profiled before the music legend’s passing in our March issue.

As our own small tribute to David Bowie, we’d like to treat this cover story as he typically directed his many exceptional guitarists by staying out of the way and letting the players do their thing. We hope you enjoy reading how this ever-curious, buoyant, and restless artist was aided by the players he trusted to interpret his work through six strings and ecstatic tempests of glorious noises.

“He Put No Limits on His Imagination”

By Tony Visconti

My job as a producer is to always interpret the ideas of my artistes. I love challenges. I work in a very unorthodox way—I start each new album as if it is my first. No presets. No assumptions. As my productions will be heard in the future, I think in the future.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

David and I always had preproduction meetings to discuss new ideas, listen to records for reference, and sketch out the outcome we wanted to achieve. I was always consulted about the choices of guitarists. We would sit down and listen to a potential guitarist, but David and I were always on the same page when it came to session musicians. Some came from him, and some came from me. Because we worked with such talented guitarists, the basic process for album sessions was to let them come up with the first idea. Then we’d start bringing the player around to the way we heard things. I’m pretty good at dictating parts and calling out the notes by name. I rarely notate, because that makes the guitarist turn down (hardy, har, har). I never touched the amp settings on any of the guitarists—except for David—but I’m pretty good at describing what I want in very specific terms. We would also record lots of alternative parts that we would edit at the mixing stage—even back in the analog days.

I worked with a lot of great guitar players during my time with David. Here are some notes about each one…

MICK RONSON

Picking the guitarist kind of set the tone for each album. It started with Mick Ronson. When his friend, drummer John Cambridge, introduced us, and we had a jam with him, The Man Who Sold the World almost wrote itself. I can’t emphasize enough how much Mick was the missing link. He was a super rock-god player, and an aficionado of Jeff Beck - who was one of our gods, too. He also could read and write music - a bonus for me.

I also remember being completely free to do whatever we wanted on The Man Who Sold the World. We never saw an A&R man during the entire recording, so we let our imaginations soar - all of us. We were David’s session players. We were a band. And we played loud! We played heroically - as if it was a live gig. Mick’s three knobs on his Marshall were usually at 10, and he used his wah pedal as variable midrange EQ.

CARLOS ALOMAR

When Mick left, the vacuum was filled by Carlos. Like Mick, he brought something extremely new and important to the next major direction. Carlos is an all-around genius player. He plays every genre really well - he is probably David’s most versatile guitarist, comfortable from funk to the avant garde - and he was always at the forefront of guitar-pedal technology. David liked the guitar playing on a demo he was sent, and he called for the guitarist to audition for the new “blue-eyed soul” record he was recording at Sigma Sound Studios in Philly. I was there the day Carlos walked in with his Gibson ES-355 and a small amp, accompanied by his wife Robin and their friend Luther Vandross. That ES-355 was wired for stereo, and each pickup always went to a separate amp with separate effects. When you hear Carlos on record, those “two” guitars you’re hearing are actually one live take. I would pan each amp to the extreme left and right, respectively.

EARL SLICK

Earl plays with the most swagger and the highest volume of all of Bowie’s guitarists. Like Ronson, he has created some very iconic guitar parts.

RICKY GARDINER

For Low, David really wanted to go “out there,” and I was working with a husband and wife duo in London, Ricky and Virginia Gardiner. Ricky was—and still is—the most adventurous guitarist I have ever worked with. He defies description. He was a resounding success for Low, and he took us to unexpected places. Bowie loved his input. Ricky would have stayed with us except for a strange illness he developed—an electromagnetic hypersensitivity allergy irritated by radio waves, microwaves, air pollution, etc. He and Virginia live in the Welsh countryside away from big cities, and Ricky still records and composes.

ROBERT FRIPP

Give Fripp a chance to plug into Brian Eno’s Synthi—the briefcase synth with the joystick—and all hell breaks loose. Mixing Heroes was no picnic. A lot of Fripp’s parts were ecstatically out of control, and a lot of it would have to be tamed with judicious comping and submixing. His choice of notes were always the ones you never expected. To watch the two well-spoken Englishmen in action was like being in an episode of The Twilight Zone.

ADRIAN BELEW

Adrian is a rock guitarist with great taste in notes, great technique, and great ideas… on acid! This is only a description - no acid was ingested on Lodger. His solo on “Boys Keep Swinging” is very bizarre, but completely accessible - very Zappa, in fact.

CHUCK HAMMER

The man showed us the first guitar synth we had ever seen and knew how to play the damn thing! We thought we were in the future the day he played the lush strings on “Ashes To Ashes.”

REEVES GABRELS

I regret that I never got to work on more than one song with Reeves. He’s a great guy, and he can play anything. For example, just when I thought I was getting something great out of him on “Safe (In This Sky Life),” David said in Reeves’ presence, “Take him out of his comfort zone. Take that Parker Fly and give him the Les Paul Junior to play,” or something like that. He played brilliantly.

MARK PLATI

Mark is so extremely talented. He plays everything on guitar well, and he’s a killer bass player, too. He had a good long run with David as a co-producer. We worked together on Reality and Toy. His guitar playing was always the right thing to do.

DAVID TORN

Dr. Ambient Guitar. He comes to the studio with a 16-space rack of some heavy-duty effects and cooks up loops on the spot. What he did on the opening track of Heathen, “Sunday,” is something completely different. I should say here that we never typecast our guitarists. For instance, with David, we once told him to turn off the ambience, and just play a rock solo that you would expect Earl Slick to be called in to do, and Torn shredded. We did this part experimentally, but mainly because we were often too impatient to wait for someone else to come the studio. If an assistant engineer was a guitarist, we’d ask him to play something if we couldn’t. This happened during The Next Day with engineer Brian Thorn from The Magic Shop studio in New York City.

GERRY LEONARD

David’s last musical director. His approach is similar to Torn’s, but Gerry is more of a rocker. He manages to add a kind of Celtic yearning in his playing.

BEN MONDER

Ben and I worked alone most of the time on Blackstar. David had a few guitar ideas he couldn’t play himself—although he did play a good deal of guitar on the album. After Ben worked with David present, we were left to add whatever I felt needed to be done. Ben definitely has his own sound—dark and ambient—and he played a couple of blistering solo parts on Blackstar, much to our delight. I look forward to working with Ben again sometime.

DAVID BOWIE

David was the type of musician who would pick up any guitar in the room and start playing cool riffy things. He came up with great hooks for his songs. Over the years, David often played a lot of riff-based lines himself, including most of the guitar on Diamond Dogs—though he did not play the “Rebel Rebel” riff. He was not a virtuoso, but his feel was so on the money. He had no problem with me tweaking his amp settings—“whatever works” worked for him. He would describe an effect, and I would come up with some plug-in alternatives, or just stick his guitar through my extensive pedals—which are mainly from Roland/Boss.

From Heathen onwards, he started to collect some cool guitars. He bought some Supros from EBay, and had them restored to new—including the electronics. He was fond of an old headless Steinberger guitar that he played on Heathen and Reality. For Blackstar, he started to make some very detailed demos at home, and he asked if I could use the guitars he recorded on a 24-track Zoom deck. For example, the heavy power chords on “Lazarus” are played by him. The bpm matched up perfectly, but I moved the parts around so they matched the playing of Donny McCaslin’s quartet. As very proficient jazz musicians, they were very complimentary about David’s playing. If David had a part he couldn’t play easily, he would delegate it to me. We had a very egoless relationship in the studio. We just did what worked.

I don’t think there will ever be anyone like David again. He put no limits on his imagination, and he recognized that in me. We were like two kids in a toy factory. I think he has made a point with Blackstar that it’s possible to make great art that will also be liked by the general public. He wasn’t about recycling rock and roll, or using analog tape, or getting a Top Ten single. He was all about art.

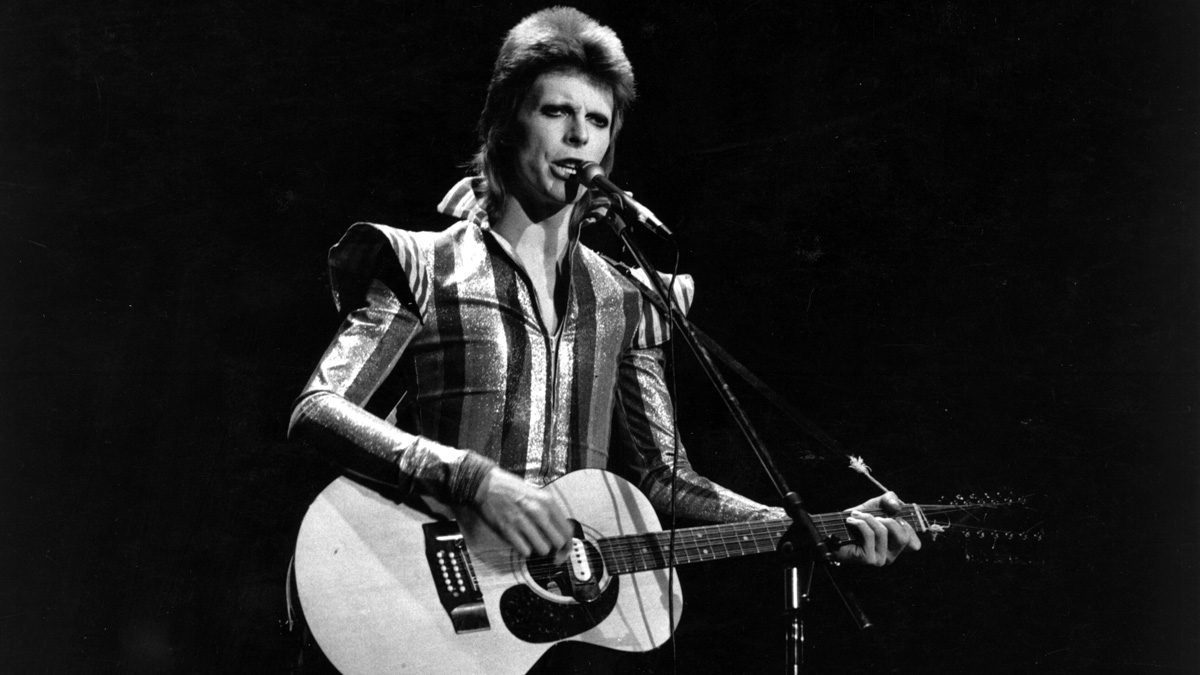

Jeff Beck Meets Ziggy

Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars: The Motion Picture, D.A. Pennebaker’s celebratory film of the band’s July 3, 1973 concert at London’s Hammersmith Odeon, documents the murder of Bowie’s beloved alter ego by Bowie himself (“Not only is this the last show of the tour, but it’s the last show that we’ll ever do,” he says from the stage). The film also features Jeff Beck trading solos with Mick Ronson on “Jean Genie,” a bit of “Love Me Do,” and “Round and Round”—not that anyone who saw the flick in its original theatrical release would know this. Beck asked to have his performances removed in the final cut of the film, and the alleged reasons for his action have passed into Bowie myth: He didn’t know the concert was being filmed, or he was disappointed in his solos, or he hated his clothes. Your call. However, the late Mick Ronson cast his vote for Beck’s wardrobe.

“I was too busy looking at his flares,” Ronson said in an interview about performing onstage with his personal guitar hero. “Even by our standards, those trousers were excessive.”

“Plug In, Turn Up, and Away You Go”

By Mick Ronson

David wanted to put a band together, and I happened to be there. I used Fender amps in the beginning, but for the Ziggy Stardust days, I switched to Marshalls. That’s when it started getting noisy! But, often, I wouldn’t even think of what I was plugging into. Sometimes, it doesn’t matter to me at all, as long as it works.

I remember playing on the road once with a guitar that had a cracked neck, and we got gaffer’s tape to fix the thing up. So there I was onstage playing this axe with gaffer’s tape. I don’t know how the hell I did it. If something went wrong with the guitar, I’d just ignore it. I’d sort of bash it about a bit, tune it up, and never bother with much more than that.

Ziggy was a very quick album to do - which made for great energy. You had the song down, you’d go in, record it, do a couple of overdubs, and it was done. That was the essence of it. We didn’t do too many takes.

A lot of the guitar sounds on the records were played with a Les Paul. I’d also use a CryBaby wah pedal. I’d set it on a sound and leave it like that to get a very midrange, honking tone. The rest of it was basically plugging in, turning up, and away you go. The equipment helps a little bit, but, more often than not, it’s in your own personality and your fingers.

It doesn’t matter what the public thinks about my playing, as long as I’m enjoying myself. Some people will probably think to themselves, “Why is he playing that hillbilly stuff? Why doesn’t he just go back to what he was doing?” And that is a good thing to do now and again. It’s always good if you can keep up what you’ve done in the past, as well as develop yourself in the present. You never know when you’ll want to use what you’ve learned before some time in the future. Of course, I hope everyone will like my music, but, either way, I have to keep moving on.

Quotes from the great Mick Ronson were culled from Steve Rosen’s December 1976 Guitar Player article - the only time we talked to Mick - and the 1996 BBC documentary, Hang On To Yourself.

“If It Felt Great, It Was Done”

By Earl Slick

It’s funny. When I did David Live, all I had was my ’65 Gibson SG Junior, an MXR Phase 45, and a late-’60s Marshall half-stack. That was it. I used, abused, and cast off tons of gear as my time with David continued, but my 1968 Gibson J-45 - which I bought new from a mom and pop music store in 1970 - is on every Bowie record. It’s also on [John Lennon’s] Double Fantasy. It’s just a magic piece of wood, and it feels and sounds great.

David never asked me to play certain things. It was always, “Slicky, do what you do.” And this is where part of David Bowie’s genius lies - when he picked musicians to work with, he picked them because of what they did and how they sounded. He didn’t want to turn an apple into an orange. He’d often bring in skeletons of the songs. Very rarely did he have the whole thing written. So we’d sit on a couch or on the floor and fiddle around. I’d say, “Let me hear the song.” He might want me to take one of his ideas and mess with it until I got it where he wanted it.

Slicky and the Boss during A Reality Tour, 2004

As far as my full body of work with David, Station to Station is my favorite record that I ever did with him. I’ve always loved Carlos Alomar’s playing, and we had a very good musical relationship. We played so differently that our parts interweaved like a perfectly made puzzle. I’d say that Young Americans is Carlos’ album - even though I’m on there. Station to Station, on the other hand, is me doing most of the guitars. For example, David wanted to redo “John, I’m Only Dancing,” and he asked if I could come up with a riff for it. Well, the riff I wrote was meant to freshen up an old song, but David decided to write a brand new song around it, and that song turned into “Stay.” “Golden Years” - which is my riff, as well - is a combination of two riffs that I stole from other guitar players. I adapted the main theme from Cream’s “Outside Women Blues,” and there’s also a hint of Wilson Pickett’s “Funky Broadway” in there.

When we were working on material for Station to Station, David and I would stand in front of a wall of Marshalls at the far end of the studio, with everything feeding back, and [producer] Harry Maslin looking cross-eyed and wondering, “What the f**k are these guys doing?”

We would usually track basics exclusively live until Reality. That album was done in pieces. I remember playing on the title track, and David didn’t have the key or the chords or anything, so I was running through the thing, just fiddling around trying to find out what to play. And you know what? Some of that stuff is on the record. I guess I hit a couple of sweet spots here and there while I was learning the song. That’s how loose David did things. Perfection had nothing to do with anything. If it felt great, it was done.

One of the funny things about David is that he would get so involved in what he was doing that he’d forget about some of us. I don’t mean this in a bad way at all. He was just so focused. When he started The Next Day, I didn’t know anything about it. The band was sworn to secrecy. About that time, I got in this car accident, and within the hour, it hit the web like crazy. So I get an email from David asking if I’m all right.

“Yeah. I’m fine.”

An hour later, he emails, “So I guess you’re okay.”

“Yeah.”

“What are you doing? Are you busy?” This goes on for 48 hours—blah, blah, blah.

Finally, he says, “I’m making a record and you need to come down and play.”

I think he was just completely focused on making the album, then, all of a sudden, my name comes up in the news, and, bingo, I’m on the record. I’d expect nothing else from him. If he acted normal, I probably wouldn’t have lasted with him for so long.

I had a chance to work with Mick Ronson when he produced the demos for my first album in 1976 [Earl Slick Band]. He didn’t get the nod to produce the actual release - which is a shame - because Capitol Records didn’t think he had the experience. They didn’t know all the arranging and producing he had done with Bowie and for Lou Reed’s Transformer. Mick was great at “hearing” the end of the song almost before you did the beginning. He could envision what a song could be even in an extremely raw form. He was such a great arranger. I loved Mick to death. We were good old drinking buddies.

Mick was probably one of the few guitar players I’ve heard who could come across with that angst and aggression, but be melodic at the same time. He wasn’t a wanking player, either. Every note Mick played meant something. Out of every guitar player that David ever had, I think Mick Ronson is better than all of us put together.

“He Was Always Curious About the Way I’d Come Up with Crazy Arrangements”

By Carlos Alomar

Young Americans was actually my second collaboration with David Bowie. I was 23 years old and working at RCA Studios as their in-house guitarist, and I was contracted to work on a session he was producing for the British singer Lulu. We hung out together. We went to the Apollo theater and other nightclubs, and we just had a great time. He’d come to my house for dinner and we’d exchange R&B and rock and roll stories. Later, he called me to do the Diamond Dogs album, but I was unavailable, as I was touring with the Main Ingredient (“Everybody Plays the Fool”), and that’s when he got Earl Slick.

Ultimately, David asked if I would do the Philly album - Young Americans - and he said we’d really have a good time at Sigma Sound. At this point, I really wanted to work with him, but as I was married, he’d have to match my price. We negotiated, and I left the Main Ingredient and I went with David. (Here’s a little-known fact: I was to be Luther Vandross’ bandleader - which we had dreamed about since we met in our teens. But we never realized our dream, because I decided to tour with David.)

For the next album, in order to achieve the rock/funk/electronic hybrid David was looking for on Station to Station, I knew that the rhythm section had to change [The main Young Americans rhythm section was Andy Newmark on drums and Willy Weeks on bass]. I really wanted to use Dennis Davis and George Murray. I had already worked with Dennis in Roy Ayres Ubiquity, so I knew what he could do, and George Murray played the most melodic bass lines I’d ever heard. David was delighted with this arrangement, because we were able to immediately create two styles that were basically mixed into being one. We were also able to flip the beat around, and hold down the slow, dredging tempo. Plus, I found out from the Musicians Union that, because of disco music, if a song is over four minutes long, you can get extra money. So I made the introduction super long for this reason. David and I would laugh about this for years to come, as that song was about ten minutes long!

Earl Slick’s power and expression is always reminiscent of the great rock and roll power players. When Slicky came in to do his part for “Station to Station,” his challenge was to hold feedback notes for a ridiculously long time. I helped him with the chordal transitions, and I thought it worked out great, as Slick and I always complement each other. He’s lead, I’m rhythm, and I can clearly state for the record that, although I play lead as a melodic expression sometimes, my heart and soul truly lie in the path laid before me as a rhythm guitarist. It’s like, East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.

Obviously, I was able to work with a lot of David’s guitar players, but here’s another little-known fact: I have never met Robert Fripp or Chuck Hammer, as they did overdub sessions. It’s regrettable, because I am a big fan of both of them - Robert Fripp because of his innovative techniques and the ways that he looks at the fretboard, and, of course, Chuck Hammer because of his work with his synthesizer guitar. Ricky Gardiner is a lovely, sensitive man. I enjoyed my time with him immensely. His technique is extremely melodic - almost like a vocalist would sing. Adrian Belew is a hammering monster and his whammy bar technique is unequaled. I cannot say enough about Reeves Gabrels’ musical expression. Not only does he have awesome chops, his innovative use of pedals and effects illustrate his total mastery of his sonic palette. Peter Frampton is indeed the Rock God that everyone claims. He understands rock, blues, jazz, and tone, and he can play endlessly without ever repeating a line.

Needless to say, I learned a lot from their techniques. Thanks, fellas!

My stereo Alembic guitar, “Maverick,” was my inspiration for all my Bowie sessions and touring. It was made for my hands, and it allowed me to play effortlessly, and joyously create my arrangements. I have never used it for anything other than David Bowie music. David always gave me free range, and he was always curious about the way I’d come up with crazy arrangements and alternate chording and rhythms. He never really addressed his musical or stylistic evolutions with me. He simply understood that I could change and be the chameleon he knew I could be. I feel that our friendship, fellowship, and camaraderie helped guide things. There’s a certain comfort we shared that allowed David to feel that everything would be all right. So much so, that he became my next-door neighbor.

As musical director for David, I paid personal attention to the musicians to make sure they were having a good time and felt comfortable. Also, I didn’t tell them exactly what to play. I liked to say, “It would be like having Jimi Hendrix as a guitar player and telling him what to play. That’s not a good idea, as it breaks the musical flow and would not allow him to express himself within David Bowie’s music.” Anyway, David would later tweak their performances according to his needs. My rules were very simple: Play it like you wrote it, be yourself, and have fun.

Overall, it is extremely important for musicians to listen to each other. There is a big difference between overplaying and listening for the holes. Create that groove, lay that pocket down heavy, and don’t fill it up. If you can’t create a good song with just four instruments, then maybe it’s not a good song. No additional production is going to make it any better. My methodology is simple: Write the song, decide on an arrangement, start the production, and respect each other.

FRAMPTON’S COMEBACK

Peter Frampton declined to do a new interview for this article, but armed with his Suhr guitars, he was a rocking presence on 1987’s Never Let Me Down and the massively theatrical Glass Spider Tour - exposure that couldn’t have come at a better time for him. “The ’80s were a difficult period for me,” Frampton told Eric R. Danton of mmusicmag.com in 2012. “It was my dear friend David Bowie who got me out on the road and reintroduced me as a guitar player around the world. I can never thank him enough for believing in me.” In 1987, Frampton gave journalist Steve Newton a peek into the studio process for Never Let Me Down. “The most frustrating thing about doing sessions for other people is when they don’t know what they want,” he said. “David is the first person I’ve worked with who has a picture of exactly the way he wants it to go. If I was slightly off the direction he wanted, he’d just get his demos out and play them for me.”

“The Tape Would Start Rolling, and I’d Take It from There”

By Ricky Gardiner

David phoned me about coming over to Paris to play lead guitar on his latest album. I had just finished touring for many years with Beggars Opera [a progressive rock band Gardiner founded in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1969], so I readily agreed. By that time, I had been playing professionally - meaning “for money” - for 15 years, ranging from the music of Henry Mancini to Hank Williams. Back then, my own preference, with regard to guitarists, was Hank Marvin. He had immaculate timing, and I used to play most of his recordings after school. First, on an old acoustic, and then on a Futurama III - which was basically a Stratocaster copy with the advantage of independent pickup selection. In all other respects, it was inferior to the Strat.

When I eventually got my Stratocaster, it had an alder body (which is brighter than ash) and a one-piece birdseye maple neck. These attributes contributed to a lightness and brightness that allowed a singer’s voice to emerge in a performance or mix. This really mattered if one was playing in larger ensembles - as I occasionally did - where brass instrumentalists took solos. I played the Stratocaster on the Low sessions, and a young Seymour Duncan - he worked in London at the time - had sorted out the difficulties I had been having with the tremolo arm bending and breaking, together with the humming from the single-coil pickups. While he was at it, he added a midrange boost and toggle switches for each pickup.

During the sessions David and Tony [Visconti, producer] left me to it - although David sang the first few notes of what he wanted in “Always Crashing in the Same Car.” Tony would start the tape rolling, and I would take it from there. I tracked both live with the band, and on overdubs, and I thought Tony did well getting a clear sound out of the very small amplifier that was available to me. I was used to stacks and the like.

I wasn’t there from the start, so I don’t know if there were any pre-production talks about Bowie’s musical direction and stylistic shift - which happened mostly on side two, in which I did not take part. It was business as usual for me. I played the songs as they came along, together and separately with Carlos [Alomar], who is an innately musical person. He approaches a work with a view to practically solving that which he encounters, in a definite way, and consistent with his experience, abilities, and technique. Carlos and I explored many subjects, but guitar playing was not one of them.

Guitars and the musical life that follows have changed a lot over the years - mostly for the better. For example, when I started playing guitar in 1959, actions were very high, strings were only heavy gauge, and gigs were long. But the only gigs we did for free were for charity, or at a party. We needed a broad repertoire, which was good training. The advent of the long guitar solo - up to half an hour - was also good training. After all, a solo is nothing more than spontaneous composition.

“He Was An Easy Person to Collaborate With”

By Adrian Belew

Right Track Recording was on a typically worn-down part of 48th street in Manhattan. From the outside, it could have been a shoe repair shop. It was there on a cold night in January 1990, I found myself standing on one side of an AKG C-24 microphone, headphones on, and about to sing the first verse of a song called “Pretty Pink Rose” [from Belew’s solo album, Young Lions, released in 1990 while he was guitarist and musical director for Bowie’s Sound + Vision tour]. On the other side of the microphone was another singer with his headphones on. It was at that very moment my mind and body chose to fully realize I was about to sing a duet with David Bowie! Blood rushed to my face like an acute case of embarrassment. I felt flushed and momentarily uncertain how to make my voice sound. The long lead-in to the track began, and, suddenly, David launched into his first line. I followed. It didn’t take long before we had the song complete, and we began working out an idea for backing vocals (“Take me to the heart, to the heart…”). Phew! I did it. For me, David was an easy person to collaborate with. If he liked something, he would be very encouraging - even excited. If he didn’t like an idea, he would calmly start out saying, “I’m not quite sure...” There was no sense of pressure, and, usually, a good dose of humor. We had fun together. After completing the “Pretty Pink Rose” vocals, I had the engineer put up another untitled track I had recently recorded. The idea was for David to write words, and perhaps record a vocal. I was very hopeful it would work out, and did it ever! To my amazement, David sat on the studio couch with a yellow legal pad, listening to the track over and over. Sometimes, he’d instruct the engineer to go back to a certain section, and then he’d busily scribble away. In just 30 minutes, he had written the words for “Gunman” - our second collaboration. He allowed me to “produce” his performance. At one point, I asked if he would mind talking through the lyrics. It was probably an uncomfortable idea, but he gracefully gave me two takes. “Graceful” is a term I would use for everything to do with David Bowie.

I toured the world with David two times and about a decade apart. On the first go-round in 1978, my guitar rig was a model of simplicity - a pedalboard with a single row of eight off/on switches that controlled whatever boxes I patched into a mixer. The stompboxes were an MXR Dyna Comp, A/DA Flanger, Electro-Harmonix Echo Flanger, an Electro-Harmonix Big Muff run through an MXR 10-band Graphic EQ, Electro-Harmonix Graphic Fuzz, and a Roland DC-30 Analog Chorus/Echo. I had one battered Fender Stratocaster that I played through a Roland JC-120 amp.

In 1990, I did the second, much bigger Sound + Vision Tour that included 108 shows in 27 countries. By that time, my guitar set up was housed in a rack the size of a refrigerator weighing 500 pounds - and there was a duplicate rack, as well. The stage was a completely flat 60’ by 60’ metal grid. My MIDIgator pedalboard was flushed mounted into the stage, and my two Fender Twin amps and monitor cabinets were hung beneath the stage and facing up at me. Each “refrigerator” contained massive amounts of MIDI gear that included Roland GR-50 synthesizers and Korg AC3 multi-effects processors as the main ingredients. I had a bespoke box that housed many of my older stompboxes, including a Foxx Tone Machine and some of the Electro-Harmonix gear. I played three Fender Custom Shop Stratocasters with Lace Sensor pickups, Kahler tremolos, Bowen locking tuners, Roland synth pickups, custom finishes, and a ridiculously long MIDI cable that could stretch the width and depth of the stage.

Only David and I were allowed on the huge stage. The band was closeted off in a back corner behind an opera scrim. On our first night of the tour in Quebec, during one of my lengthy guitar solos while David stood in the middle of the stage watching, I ran from one side to the other back and forth like a good show-off rock guitarist is supposed to do. Only when I stopped did I realize I had roped David legs together with my ridiculous MIDI cable. He introduced me then as the “Fred Astaire of electric guitar.”

I’d like to think that playfulness and a boy-like spirit is what I brought to the Bowie shows. As I said, we had a lot of laughs. On his records, I was more than willing to be adventurous, which is what he wanted. He never instructed me, but instead gave me free rein to go wild. David Bowie was free-spirited, intellectually curious, utterly unique, and wealthy and superstar famous, yet down to earth to those around him. He was an incredible person to know. I am a lucky boy.

“He Pushed Me to Never Hold Back”

By Reeves Gabrels

In the best possible way, my role never seemed clearly defined. It was co-writer, co-producer, confidant, and, of course, guitarist. Being art-school boys, David and I settled into a conspiratorial friendship early. Throughout the following 13 years and the 40+ songs we wrote together, the studio was our Buckminster Fuller sandbox - our safe place to create where time stopped and art was made. There was no careerism - or attention to a “marketplace” - but, instead, a desire to tell a story and to leave a trail of good work. During our time together - contrary to the conventional view of David as a calculated manipulator of image - we felt more kinship with various art movements (the Beats, Fluxus, German Expressionism, the Constructivists, etc.) than we did any competition with the music being made around us. The big lesson we took from these various art movements was the concept of the “manifesto” - the idea of what we wanted the music to be, which was as much defined by what we would not do, as it was by what we could do.

What would always happen in the space between the end of a tour and the point where he and I would get together to start “making stuff,” is that, in the time apart, we would individually and separately discover different things. For example, between Tin Machine and Outside, I got bitten by the industrial-music bug, and sent him NIN, Pigface, and Ministry. Before we began Outside, he was sending me drum & bass cassettes (Roni Size, Goldie). Before Earthling, we both stumbled across Photek, Squarepusher, and Underworld, and we pushed those influences through our brains/ears/filters.

My involvement as co-writer and co-producer meant I was also trying to get the sounds to - as Vernon Reid once said to me - “shake hands with the songs.” That, in turn, played a major role in the guitars I played, the gear I used, and how I used it. Here are some highlights…

TIN MACHINE

In 1988, I went to David’s house in Switzerland for a weekend. I ended up staying for a month. We realized we both had been listening to similar things: Glenn Branca, John Coltrane, Hendrix, Cream, Led Zeppelin bootlegs, Stravinsky, Miles, the throat singers of Tuva. Freaky. Manifesto in place, we began recording at Mountain Studios, Montreux, Switzerland in earnest - a song a day, top to bottom - and we knew we were making a snotty, f**k you rock album. I adjusted my gear accordingly: Steinberger GL-2T (on every track), 1962 Stratocaster (that Marc Bolan had given David, which I found in a flight case in David’s basement), 1963 refinished Stratocaster (used on half the album’s solos), 1956 refinished Les Paul Junior, 1962 Gretsch Nashville, and a Gibson SG that had belonged to Angus Young.

I ran four amps at all times - a plexi Marshall and 4x12 (David claimed it had been one of Mick Ronson’s spares - I also found this in David’s basement), Mesa/Boogie Mark III (the same amp Brian May used on Queen’s “Crazy Little Thing Called Love”), Vox AC30, Fender Princeton. Effects included a Chandler Tube Driver, Dunlop Fuzz Wah (with Roger Mayer upgrade), Ibanez HD1500 Harmonizer/Delay, Ibanez UE405 Multi Effects, and a Pro Co Big Box Rat.

BLACK TIE WHITE NOISE

After Tin Machine disbanded, David decided to do a “Let’s Dance, Part 2” with Nile Rodgers, and he was recording a song I had originally written for Tin Machine entitled “You’ve Been Around.” I went to the studio with my live rig for the scheduled two-day session for my parts, and I had a little chat with Nile about how to record my amps. He insisted that I record direct using a rackmount ART guitar preamp. I resisted. Unless I was playing clean parts, I felt my rig was the way to go. We miked up my stuff, and I reluctantly agreed to try the ART unit the next day. Well, for the next two days, Nile did not come to the studio. Oops. So I tracked using my amps with David and engineer Richard Hilton, and I had a great time with David, as usual.

I played on “You’ve Been Around,” did wah and power chords on “I Feel Free” (which Mick Ronson did the solo on), and wah on “Nite Flights.” Sadly, I am only credited with guitar on “You’ve Been Around,” which was disappointing, as Mick was such a huge hero and influence, and the fan boy in me just wanted to have proof I was on a track with Mick Ronson. And so it goes...

OUTSIDE

It was March 1994, and in the days of faxes, David, and Brian Eno, and I were continually faxing back and forth regarding the “what if’s” and “how’s” of the record that would become Outside. We went into the studio with written songs, a lot of pure improvisation, and three pieces where Eno wrote out sci-fi scenarios to influence the improvisations. At the end of five weeks, we ended with what I think of as a two-hour, double-album “improvised opera.”

I knew I would need a versatile rig for all of this improvisation. I had been good friends with genius guitar maker Ken Parker for years, beta testing his designs (“Here, Reeves, take this and see if you can break it”). So I took one guitar - a white, tremolo- equipped Parker Fly Deluxe with a piezo bridge. The electric pickups were plugged into a Mesa/Boogie TriAxis, Mesa/Boogie 2:90 stereo power amp, two Mesa/Boogie 1x12 speaker cabinets, DigiTech IPS-33B, Eventide H3500, Rat distortion, MXR Phase 90, Roger Mayer Axis Fuzz, Dunlop wah, DigiTech DL-8, Univox Unitron 5 Envelope Filter, Electro-Harmonix Frequency Analyzer (that once belonged to Jake E. Lee), and Fulltone DejaVibe (serial number 003).

The Parker’s piezo pickup was routed to a Prescription Electronics Experience Fuzz, DigiTech DL-8, DigiTech Whammy (after the DL-8 looper so that I could change the pitch of the loops), a DigiTech IPS-33B, and everything running in stereo to two Fishman acoustic-guitar amps. Of course, the whole rig was operational and ready at all times. For example, while tracking live, there are instances where you’d hear a mangled electric-guitar loop, and, then an acoustic guitar sound would suddenly appear over the electric loop. I have to thank my guitar tech at the time, Andy Spray, for helping to “make it so.”

It is also important to note that this record was done before we had Pro Tools. All we had was a 48-track Sony digital machine, a Studer 24-track deck, a half-inch stereo reel-to-reel, and a razor blade - amazing in its comparative primitiveness now; state of the art then.

The key to knowing which of the Outside songs were generated in which manner is in the writing credits. If there are six writers, it was improvised - such as “The Hearts Filthy Lesson.” Less writers than that means the piece was written in advance of hitting Record - “The Voyeur of Utter Destruction (as Beauty),” for example. This was DB at his finest Miles Davis/art director approach - getting a bunch of highly capable players together (each with their own evolved vocabulary), and letting them react to stimuli. Unfortunately, when it came time to get a record deal, the business people wanted a hit single and a single disc. For a long time, I couldn’t listen to the album, because what it became was not it was intended to be.

THE ROLAND VG-8

The Outside tour started in late August 1995, and in April 1996, the production manager and the “counters of the beans” asked that we cut back on gear. It was suggested that I use a pedalboard and a hired backline. Instead, I decided to use the new Roland VG-8 and S-1 upgrade card that allowed for altered tunings and Whammy-pedal-style effects. In the meantime, Ken Parker built me a Fly Deluxe with a single Roland hex pickup. As a result, several reviewers decided that I was miming my part because my guitar didn’t have any visible pickups on it. That was hysterical. Then, while touring Japan, Japanese guitarist Hotei gave me one of his signature Fernandes guitars for my birthday. Suddenly, I had the perfect combination for where I was at back then - a Sustainer- equipped guitar and the VG-8.

EARTHLING

This was my favorite album and tour of anything I did with David. Before going into the studio to work on this album, we had seen Prodigy, Massive Attack, and Tricky at the festivals, and the combination of elements in their music impressed us. I had been writing on my laptop with a small Yamaha General MIDI synth, so I had the early crumbs of what became several songs on Earthling, and the Roland VG-8 let me get away from traditional guitar tones. I could sound like an Akai sample of a guitar, but actually play guitar.

We booked Philip Glass’ Looking Glass Studio in New York, and by good fortune got Mark Plati as our engineer. Mark and I fell in love right away. He loaded my scraps into the computer, and David and I would jam out chord ideas against the tracks I had started. We would sit around one mic with two small Fernandes Elephant guitars that had built-in speakers. One of the fun sounds - and you can hear it on “Dead Man Walking” - is the natural phasing from our strumming hands waving over the onboard speakers. It became clear that the three of us - DB, Mark, and I - were writing and co-producing the album. By the time we were done, I ended up co-writing seven of the nine tracks - one of which, the aforementioned “Dead Man Walking,” earned a Grammy nomination in 1997 for Best Rock Song.

“The Last Thing You Should Do” was written by Mark and me using the process we came to call “obtainium.” We would look through other tracks and find bits and pieces of ideas gone wrong and make something new from them. I even made a 45-minute DAT tape of me playing all kinds of stuff on my rig. If we needed a guitar hook, we loaded my ideas into an Akai sampler and I played them from a keyboard. The guitar stuff was all done with an unfinished mahogany Parker Nitefly - called “Brown Dog” - that become an art project. If someone threw a bracelet or ring onstage, I would inlay it into the raw wood. It was my main guitar for years - always changing as I stuck more sh*t to it - and it’s the one I’m holding on the cover of the June 1997 issue of Guitar Player.

‘HOURS...’

When we started writing this album in 1998, David’s idea was, since we had been at it for ten years at that point, we should consider all the songwriting as a co-write and the production as a co-production. My mind was blown.

We debated quite a bit about direction. I wanted it to be like Earthling 2.0, and David wanted something different - something I assessed as more of a singer/songwriter album. So, once again, I adapted my guitar gear and approach to suit. This was about real amps for the most part, along with vintage pedals and vintage guitars. I had 1956 and 1957 Les Paul Juniors, a 1960 Les Paul Custom, an ’80s Les Paul Custom, a mid- ’60s Gibson Trini Lopez, a 1963 Stratocaster, and a 1966 Telecaster. I also used a sparkle-pink PRS with P90s and a Parker Fly “Brown Dog” with Sustainer and hex pickups. Acoustics were a Gibson Hummingbird, a Martin D-28, and a Takamine 12-string. The amps were an old Gibson Skylark, a Mesa/Boogie Heartbreaker, a plexi Marshall, a Vox AC30, and a Fender Princeton. One thing I did with the Princeton was mic it up, and then on multiple inputs combine the miked sound with an Amp Farm Princeton, a Roland VG model of a Princeton, and a Tech 21 SansAmp “small Fender” setting. I just wanted to see if I could make the “World’s Biggest Princeton” and spread it across the stereo field.

ONWARD…

It was a dream come true that I found myself standing next to one of the world’s greatest singers and frontmen. This allowed me to push myself and the music without any worry of overshadowing the singer, because, to state the obvious, no one could beat DB. David was a force of nature. I loved that man, and I loved the times we had. He gave me the greatest gift - the confidence to be myself as a musician and as a man and to never hold back. I am proud to say he was my friend.

David never told me what to play, but he did enjoy pushing me out of my comfort zone. For example, I didn’t think that “Looking for Satellites” from Earthling needed a guitar solo. His solution was to say, “Okay. Play only thirty-second-notes and stay on one string per chord change. Stop when you get to the chorus.” I was so bugged that I was being made to play a solo that I did what he asked, but I blasted through the verse and continued through the chorus to the end of the song. One take. It is now one of my favorite solos.

I hope that David is remembered as a real person and as an artist, and that he is not turned into a once-upon-time symbol of controversy by the media - a saucy sound bite by the tabloids, or a silkscreen on a t-shirt worn by baby boomers and hipsters alike trying to create the appearance of cool without ever looking below the surface.

It would be wonderful if music fans took this opportunity to listen. Now is the time to go deep. His life’s work is waiting there to be heard - as well as the contributions of all of us that he championed.

ROBERT FRIPP IS MIA

Yes. There is no new Robert Fripp interview in this cover story. There’s also no old Fripp interview. It’s somewhat baffling that Mr. Fripp was intervi - but nothing exists from Fripp’s own mouth about his work on Heroes and/or Scary Monsters.

“He Had a Deep Interest in Experimental Guitar Textures”

By Chuck Hammer

I met David Bowie In October 1979, while on tour with Lou Reed in London. During that tour, I was using a Roland GR-500 guitar synth as my main instrument. David attended one of Lou’s concerts at the Hammersmith Odeon and expressed interest in working together. In late 1978 through 1979, I had been recording experimental tapes with the idea of layering sustained guitar tracks to build up textures. I referred to this idea of multitrack layering as “guitarchitecture.” The core idea was to extend the guitars sonic vocabulary. Soon after meeting David, I sent him a cassette with four experimental guitarchitecture tracks. A few weeks later, I received a phone call from David’s assistant asking if I would be interested in working on David’s next album, Scary Monsters, which was to be recorded at the Power Station in New York City during February and March 1980.

RECORDING “ASHES TO ASHES”

Chuck Hammer

The session was done privately with just David, Tony Visconti, an assistant tape op, and myself in the studio. Throughout the session, David and Tony were intensely focused. Upon entering the control room, David mentioned that he had listened to the earlier cassette tape extensively. They began the session by playing the basic track that would eventually become “Ashes To Ashes.” The submix they chose to play was a sparse basic instrumental track containing only bass, drums, rhythm guitar, and a minimal keyboard without vocals. Because this basic track was intentionally sparse and open, it allowed room to imagine adding a wide range of possible guitar textures.

After listening to the initial playback, neither David nor Tony said anything, politely waiting for my reaction. I noticed a few similarities to one of the experimental tracks from my cassette tape as a reference point. Certain sections within David’s basic track seemed like they could be developed with layered guitar-synth textures. Those sections would later turn out to be the vocal chorus sections of “Ashes To Ashes.” As mentioned, there were no vocals on the submix track at the time - or at least David chose to not let me hear any vocals as reference.

I suggested that we try to multitrack the GR-500 as a textured guitar choir with stacked, sustained chord inversions. David was very open to the idea, and he simply nodded his head in agreement. They had already prepared a basic chord chart for the song. I began to overdub a series of four discreet stereo tracks of layered chord inversions with the GR-500. Each layered track of chord inversions was voiced as widely as possible across the fretboard, and each pass was recorded with slightly different tape echo, Harmonizer, and GR-500 settings. As the sustained tracks were being built up, they began to sound like a guitar choir. Between takes, both David and Tony walked into the main studio from the control room. Tony made a few tonal adjustments to the Roland JC-120 amp settings prior to each take. I recorded a few additional takes with different GR-500 parameters, running the song down from end to end.

Both Tony and David tended to work quickly, and they committed to ideas early in the process. During the second playback, for example, Tony had already subgrouped the guitar-synth tracks on the studio’s Neve console so that he could test a fade across all of the guitar tracks simultaneously, treating it as a unified guitar choir. I was stunned when I heard the playback. It was an ethereal wall of guitar texture that none of us had ever heard before. We all looked at each other realizing that we had something very solid on the tracks.

TRACKING “TEENAGE WILDLIFE”

The second song we recorded was “Teenage Wildlife,” and it was much more complex. During the initial playback, I was again given a very sparse and open basic track without guide vocals. The chart for this song was complex in terms of containing multiple song sections. Tony suggested that we actually record each section separately - like a suite - using different GR-500 and Harmonizer tones. Their basic track already had a solid chordal presence, so I began to build up layers of single-note lines using the GR-500 set to Solo Mode. Robert Fripp also appears on the track in a major way, but, at the time, his tracks were not played or mentioned. It was a bit of a clever production strategy on their behalf, as they simply left it open for me to build as much density in the lines as I wanted. Because I had no idea that Robert’s brilliant tracks would also be in there, I just kept developing and layering the lines as we worked through the discrete song sections. Tony made extensive Harmonizer adjustments about three quarters of the way through the song where he wanted more density. He was deeply involved in guiding me through each section. Eventually, they mixed our guitar tracks together varying the density of the layers - like a small guitar orchestra - depending on how thick they wanted it to sound for each section.

THE SIGNAL PATH

For both “Ashes to Ashes” and “Teenage Wildlife,” my rig was as follows: 1977 Roland GR-500 Guitar Synthesizer (GS- 500 Controller with GR-500 module) into Roland RE-501 Chorus Echo Tape Delay (only tape echo engaged) into Eventide Harmonizer (set to full-octave up, 20-percent Regeneration, 20-percent Harmonizer mix blended under main tone) and out to a 1978 Roland JC-120 combo (no overdrive, no reverb, and no other pedals). The tracks were recorded in stereo to a Studer 24-track tape deck.

SOME NOTES ON THE GR-500

It’s worth noting that, although the GR-500 had a huge analog tone and a unique sustain technology, it’s intermittent tracking made it notoriously difficult to play. As a guitarist, this really forced me to rethink and modify my technique - making me think more as a composer in terms of layers and stacking textures rather than linear lines.

Let me elaborate on the GR-500’s simple- but-effective infinite sustain system: The frets in the GR-500 are connected to its electrical ground. When a player fretted a string, an electric current passed through the string. The electric signal passing through the string is a greatly amplified version of the string signal detected by the divided hexaphonic pickup. Large magnets replaced the traditional “neck pickup.” As a result of Fleming’s Law, the alternating electric current in the string passing through the strong magnetic field caused the string to vibrate and create a feedback loop and infinite sustain. The GS-500 used a bridge with plastic saddles to electrically isolate each string.

INSIGHTS & INSPIRATION

Bowie’s Scary Monsters arrived at a point in his discography that was very experimental. It was the first record he made after his trilogy of albums with Brian Eno, and Bowie asked me to step in and extend those sonic directions to the guitar tracks. The layered GR-500 tracks on Scary Monsters were the first use of guitar synthesis within Bowie’s catalog.

Although David was highly organized during the recording sessions, he was very open to experimenting. One of the first things he did during the “Ashes To Ashes” session was to walk into the main studio room where my gear was set up, and ask me to show him the range of tones that I was able to achieve. Experimenting with new tones and textures had become a hallmark of his recorded work - it was almost a prerequisite - and Bowie had a deep interest in new sonic terrains and experimental guitar textures. He also had a deeply keen understanding of how these tones could work within the wider context of his own music. One of the key insights I gained from working with Bowie on Scary Monsters was to always follow your own instincts and your own sonic language.

Because Bowie’s recordings were so widely listened to, it was not necessary for much verbal direction. Scary Monsters was one of the albums where all the ideas he had been developing on the previous three albums were extended into something new. The sense of sonic exploration and the high quality of the previous work was the inspiration.

David was an extremely polite person, and he went out of his way before, during, and even after the recordings to accommodate anything I might need - including giving me a listen to a pre-release, vinyl test pressing of “Ashes To Ashes.”

Finally, when you have musicians at the level of Carlos Alomar, Carmine Rojas, and Dennis Davis at the heart of a basic track, their musicianship brings the recording up to such a high level that it becomes essential to reach for something new in your own playing - something beyond what you might normally play. Otherwise, quite simply, your own track won’t cut it.

“I Was Basically Free to Do What I Wanted”

By Stevie Ray Vaughan

The entire recording experience of Let’s Dance helped a whole bunch, and in a lot of ways. I learned a lot about playing - particularly in terms of recording techniques - and about business. It was real fun doing the record, trying to see where my style would fit in. It was a pretty open thing, and more an experience of looking at music in different ways - of looking at big arrangements and fitting the parts in. I learned a lot about how songs are built. But the Bowie sessions were easy, because I was basically free to do what I wanted.

From what I understand, Bowie was looking for somebody who played this style anyway, and I was the one he picked. Most of the time, he just told me to plug in and play. He’d say, “Plug that blue guitar in!” I cranked it all the way up, and other effects were added later.

Nile Rodgers and David gave me some input on what needed to be done, but it was real relaxed. Most of the songs were cut in one or two takes. There was no worrying over the parts. I probably played only two or so hours over the three days it took to do the thing.

Quotes pulled from Bruce Nixon’s interview in the August 1983 issue of GP.

PETE GETS CRANKY

David Bowie and Tony Visconti had a grumpy guest star in the house when Pete Townshend was invited to play guitar on “Because You’re Young” during the 1980 sessions for Scary Monsters. Visconti remembered Townshend being in a “foul, laconic” state who barked “Chords? What kind of chords?” when asked by Bowie to play his signature rhythm-guitar style on the track. Visconti bravely answered, “Er, Pete Townshend chords,” to which the Who mastermind calmly responded, “Oh, windmills.”

“David Didn’t Hold Back From Giving Me Truth”

By Nile Rodgers

My personal technique of producing - no matter who it is - is to focus on the artist’s direction first, and what I’m supposed to achieve. I lock down the “DHM” - what my partner Bernard Edwards [Chic bassist and coproducer] would call the “Deep Hidden Meaning.” Once I know what the song is really trying to say, then I switch from that super-focused guy, and I become like an entertainer. I’m trying to have fun, to be your coach and your rooting section, and make you feel comfortable. So David would have an idea of what he wanted, and then it would be my responsibility to make sure we got that.

I always record live in the studio, and David would sing a scratch vocal, or he’d have an idea of the song that he’d talk us through. Every now and then, he would do something very funny. In those days, he’d have a little cassette recorder, and he’d play the tape while the band was playing. He’d say, “I heard this while I was walking down the street,” or “I started singing this thing to the groove in the background -listen to what it sounds like.” He used to kill me with that. It was amazing. When I was younger, I had these brilliant music teachers, and they would say things like, “Art is all around us. You just have to look for it.” And David Bowie was always looking for it. He just seemed to see it and hear it. It was like, “Okay, now let me share it with you guys.” He was an extraordinary man - a great artist.

Everybody’s performances on Let’s Dance were basically one take - including Stevie Ray Vaughan’s solos. Let’s Dance was the easiest record of my entire career - 17 days from start to finish. David did all of his vocals in less than two full days, and Stevie Ray Vaughan did all of his guitar solos in a day and a half. We walked out on day 17 and never touched the record again.

This was possible for a couple of reasons. He didn’t have a record deal, so he did Let’s Dance purely on his own. He also did some cover tunes, rather than write everything himself. And I think he was coming off an odd period in his life, and he wanted to trust me. I said, “Hey David, let me do the arrangements,” and I changed everything. There’s nothing he gave me that appeared the way it was when he submitted it to me. That’s why we went so fast. Most of the time, he wasn’t even in the studio with me. He was in a lounge watching television. He’d come out and go, “Wow, that’s great,” or he’d criticize something and we’d change it. Everything he heard, he heard with fresh ears.

For example, when I came up with the riff for “China Girl,” I thought I was going to get fired because it was so corny. I played it for him by myself, and I said, “David, the reason why I’m doing this is because this song doesn’t have a hook. It doesn’t sound like a hit, and you told me you wanted to have an album with hits, so let me put this hook in.” Happily, he said, “I think it’s fantastic.”

I also changed “Cat People” from the dirge-like version he had done with Giorgio Moroder [for the film of the same name]. I said, “David, what if you sing it exactly that dirge way, but the band plays double time, and then I play jazz-type guitar -double-stops with thirds?” We made it into a rocker. He trusted me to do that stuff.

We had so much fun, and Stevie became my best friend for life. The look on his face when he first walked into the control room and heard “Let’s Dance” was like, “Oh my god - I’m experiencing something important and magical. What do I do? How do I fit in on this thing? I have to get out of their way, and just add spice.” I didn’t have to tell him anything. He instinctively knew his role was like, “The meal is fantastic - now here’s the dessert.” And, bang, he nailed it. We couldn’t believe how quickly he would whip through those solos. He could just hear the music, feel it, and understand we were all supporting David Bowie. We were making David’s pop record.

And I’ll tell you, he didn’t know anyone in the band except for me and David, but he knew they were my friends. He wanted to bond with them so that he’d be accepted as family, too. He also knew we were making Let’s Dance like a black record. White bands would book the studio for months and months, but black records only got a few hours. We’d work an eight-hour shift because we had lower budgets than rock albums. So we would order our food at the beginning of the day, so that it was here when we took a break for lunch. We’d eat and - boom - back to work. Stevie saw we were doing that, and he called Sam’s BBQ in Austin, Texas, to order our lunch for the day he came in. We didn’t know this, so we started our lunch order, and Stevie said, “Y’all, I got lunch today.” The next thing you know, all this BBQ came in. I was like, “Check this dude out. He’s right up on the vibe.” And from that moment, Stevie and I became like brothers.

When David called me to do Black Tie White Noise, I was thrilled to work with Mick Ronson - a bit of hero worship for me. I dug his playing for so long, and now I get to become his coach. How cool is that? He was really easy to work with, and we got what David wanted. The album itself was a whole different mindset from the compositions on Let’s Dance. This was originally music that was going to be played at his wedding. He was very aware of his own life - his past and the journey he’d taken to get to where he was. He would talk about his fear of death, his brother committing suicide, and other things. So in those kinds of intimate situations, you get truth, and David didn’t hold back from giving me truth. For a producer, these relationships are incredibly special.

“He Really Wanted What You Had to Offer”

By Mark Plati

David decided he wanted to play Low in its entirety on the 2002 Heathen tour, and, as musical director, it was my job to arrange its presentation for the stage - as well as helping with the set list, running the rehearsals, making sure everyone had charts or the necessary gear, cueing endings and transitions during the show, and so on. As Low was such a dense record, I decided the most accurate and expeditious way to figure out how to represent it live would be to get the original multitrack masters and transfer them into a DAW. Then, I could isolate individual tracks and decide how to divide up parts based on each guitarist’s style, technique, and use of effects. In this case, those guitar players were Earl Slick, Gerry Leonard, and myself. Initially, I was concerned about having three guitarists on the tour. David was really into it visually, but I knew it would be a train wreck if I wasn’t extra mindful of how all the parts interacted, or if I didn’t orchestrate everything properly.

For Low, there would sometimes be four or more guitar parts on a track, which I needed to distill down to three separate parts and sounds. Then, I would make an individual mix for each player. I’d solo their part on the right side of the mix, and put the rest of the track on the left side, so that they could hear their part in context if they summed to mono. (I did this for the rest of the band, as well, which was time consuming, but it made it a breeze for everyone to home in on their parts and sounds.) Fortunately, the three guitar players had very different styles that complemented each other well. I started by taking Carlos Alomar’s rhythm parts for myself, and then I divvied up the lead and ambient parts according to whose style - Slick’s or Gerry’s - I felt fit better. I threw Gerry the most oddball parts. He made it his business to really cop the sounds - especially Ricky Gardiner’s phase shifting and dirt on the solo from “Always Crashing In the Same Car” and the warbly ska-like vibe from “A New Career in a New Town.”

The go-to gear for each of the albums I played on revolved around a generally small collection of guitars, basses, and amps. On ‘Hours…’, I played bass, and my involvement on guitar was limited to 12-string acoustic (David’s Takamine). My parts were done at the end while I was mixing the album, as there were spots on a few songs that we all felt needed it, and David and Reeves [Gabrels] told me to go for it on my own. This led to me being involved in the VH-1 Storytellers show. I knew they would need an extra guitarist for that gig, so I went ahead and asked! For that show, I primarily played the Takamine 12-string—though I also used a 1978 Gibson 355-TD (a gift from David and Reeves) and a ’67 Rickenbacker 12-string. My amp was a ’62 Fender Princeton, and I used a Korg AX1G for reverb and modulation effects. After the VH-1 gig, I stayed in the band and became musical director.

The next album I was involved in as a guitarist was the unreleased Toy—which I produced with David right after the Glastonbury mini tour in 2000. We came straight off the road, and recorded most of the album live. For my parts—usually rhythm against Earl Slick—I used a 1999 Roadhouse Stratocaster, a ’61 reissue Gibson SG (Gibson gave one to Slick and me for the Glastonbury tour), and my ’67 Rickenbacker 12. Again, I used David’s Takamine for acoustic work, occasionally mixing it up with my Martin HD-28. My amp was a Fender Hot Rod DeVille 2x12, which offset nicely against Slick’s Ampeg Reverbrocket. We ended up doing an additional session, and I added what came to be known as the “Mini Strat” - a small practice guitar given to me by guitarist Marc Shulman that tech Flip Scipio hot-rodded and brought up several notches to a truly usable standard. David loved it, and he used it to write the song “Afraid” [Heathen].

On Reality, I was again serving as bassist, but I played some guitar using my road instruments at the time: the ’99 Roadhouse Strat, an ESP Vintage Strat-style, and an ESP Ron Wood Signature Tele. My amp was a Matchless DC-30, although I remember we had a lot of fun messing about with a Korg Pandora - most notably on “Never Get Old.”

David didn’t direct me all that much. I’d often be left to my own devices, whether it was guitar, bass, or even synth programming. David would always have the big picture - the artistic overview - and then he would let us do our thing as far as how we’d interpret that overview. He really wanted what you had to offer, but, at times, he’d feed somebody a specific idea or line to play, or take a part somebody was trying out and suggest a way to twist it around - always one of the funnest parts of any Bowie session. As most of my parts were fairly meat-and-potatoes, I didn’t get a lot of that unless I missed the mark completely.

In the live context, his vocal was a prime source of direction. Not only because of the dynamic you’d follow, but just the joy of playing with a vocalist who was at the top of their game. I think that brought out the best in all of us.

During my time with David, I prided myself on being as “Bowie-esque” of a collaborator as I could be. David knew I had a musically open mind, because to be young and coming-of-age as a musician in New York in the 1970s was a special experience. We had so much thrown at us - rock, funk, disco, electronic music, and all the combinations thereof. Bowie was a big part of this, as his music crossed many of these boundaries during those years. Part of the reason Station to Station became my favorite Bowie album was that its melding of rock and soul made perfect sense to me. David changed direction several times while I was with him. I always eagerly anticipated where the adventure was going to go next, and the smartest thing I did was to roll with it.

“A Boundless Love For Pursuit of the Inexpressible”

By David Torn

Wow . David ’s gone. I can barely speak about the years during which I worked on countless tracks with Mr. B., but I’ll say what I can. First and foremost, David was a man whom I really loved and respected, and who was my friend. There are the richest of colors there that can’t ever fade.

David first invited me to work with him in 2000, and Heathen began in summer 2001. From the beginning, he was open to whatever sounds and parts I thought suitable for most of his music. If he had direction to offer, it would be simultaneously quite clear, emotionally speaking, and yet highly interpretable - which I believe was his intention.

The creative doors opened between David and me during one of the first tracks I worked on, “Sunday.” I took a few improvised passes, getting some ideas about the song’s arc, adjusting my sounds, etc. I then recorded an improvised pass exemplified by the textural bridge that occurs between 2:15 and 3:10. That is a backwards melody I recorded with a Teuffel Tesla guitar into my Echoplex Digital Pro. It was manually faded in and out in real-time against a 20-second-long, harmonically dense, polyphonic ambient loop that blooms around the appearances of the reversed melody. The ambient loop was recorded on my Lexicon PCM42, and processed in real-time with my original octave-like reverb program on a Lexicon PCM80. I mixed them with my modified Rane SM82. There were three Rivera amps set up in three-point-stereo: wet/dry/wet. I was mixing in the wet amps with expression pedals while playing, so I could add expressive effects.

After recording that, I listened to the track a couple of times, and I asked David if I might have a bit of time to work out an unusual rhythmic part - which, if it worked, would be pre-looped, yet actually performed. While no one in the studio likes to wait while insane strangers work hard, but waste time failing at so-called “great ideas,” David and Tony [Visconti] guardedly agreed, and left me to go at the part.

I set my Electrix Repeater to match the tune’s click, and played along with the piece, working out my ideas and techniques, and recording the first track into the Repeater. When I had the ideas for each section mostly worked out, I recorded those parts to each of the remaining three tracks on the Repeater. Then, with David and Tony’s enthusiastic approval, I practiced triggering, stuttering, mixing, and performing the part.

I’d used the Repeater’s four loopable tracks to build a single guitar part—one track contained tones common to all the harmonic changes within the piece up to 2:00, and from 3:10 forward. The other three tracks were suited to specific harmonic regions. In order to make the transition into the bridge, one track was set up so I could manually transpose it via a small keyboard. I had assigned a volume fader to each of the four tracks, and I programmed a knob on the keyboard to stutter the start of each phrase, or wherever I felt a stutter/glitch might be useful. I think the entire process - including coffee - took about two hours. This multi-voiced rhythm part begins the song. It’s just my part and then David’s synth.

David also had a great love for old Supro amps, and, while we were recording “The Next Day,” he presented me with Marc Bolan’s Stratocaster - which Marc had given to David - to play. Amazing! It was amazing to work with David for 15 years, knowing that someone I respected so much enjoyed, encouraged, trusted, and reveled in this kind of work process, and in endless travel through the imagination with a boundless love for pursuit of the inexpressible. Excelsior, DB.

“He Loved the Guitar and Understood Its Complexity”

By Gerry Leonard

Working with David was the highlight of my guitar-playing career without a doubt. He taught me so much about how to play rock and roll by being by his side. It was almost like getting a transmission from a higher being. He taught me to stay rooted in the storm, but also how to soar and drive off the cliff at full speed, and even land safely. I did two big tours with him over the years. One tour was where we played the Heathen and Low albums back to back, in their entirety. This was a real challenge and an education to decipher, as well as execute those wonderful guitar parts live, from the unmistakable Brian Eno processed sounds to complex loops from David Torn.

I ended up then becoming his musical director for the 13-month Reality tour, taking over from Mark Plati, which was a great honor. This was a huge undertaking with full production and crew, eight trucks, nine buses, and an airplane. Even our repertoire was huge - it grew to more than 65 songs. All throughout, David was the best boss you could have asked for - clear about what he wanted, and yet flexible to allow the band to contribute and shine.

I got to be involved from the ground up on The Next Day. He called me early on to help flesh out his demos. I brought a small rig and two small amps to this tiny rehearsal room in Manhattan, and with Tony Visconti on bass and Sterling Campbell on drums, we dug in for the week. At one point, I was embarrassed as David was singing in front of my amps, which were cranking. I asked him if it was too loud, and he just grinned and said, “Nah, I like a bit o’ loud.” This reminded me of when we were in rehearsals for the Reality tour, and he stood in front of me and said, “Sounds great, Gerry, but can you turn it up?” David was probably the only singer I have ever worked with who told me to turn up!

Whenever I got to record with David, I liked to pick out some special and esoteric gear. When we recorded “The Next Day,” we had constraints in regard to separation, as David wanted everyone to play live. I called up Mesa/Boogie and got two small 1x10 cabs that we stacked up facing opposite directions. We put a Shure SM57 on one side, a Potofone ribbon mic on the other, and we locked up the cabs in a giant road case. I drove the cabs with a Mesa/Boogie TA-15 and a Sommatone Roaring 40. It was a really killer sound - super punchy and yet spacious. I also brought my EMS Synthi Hi-Fli - a rare effects console from the ’70s with faders to dial in sounds, and its own chrome stand, like a piece of furniture.

Over the years, I have amassed quite a collection of odd but interesting effects, including vintage Ibanez, Z. Vex, Electro- Harmonix, and Lovetone pedals - all wired into a custom switching system that I built. I used combinations of the pedals for distortion and color, depending on the song and the part. In the studio, I needed to work fast and play takes very much in the vein of a live performance, and, this way, I could go from a dry, straight-amp sound to super-wide cinemascope by clicking one button. For playing live with David, I built a complex system using the Voodoo Labs GCX Guitar Audio Switcher, which gave me scenarios such as using an Eventide H3000 as a stompbox.

For guitars, it always felt best to pick ones with personality—like my trusty, threepickup ’69 Gibson SG Custom (that I’ve had since I was 16 years old), or my ’65 Firebird with P90s. I also have some lo-fi guitars - like a Teisco Del Rey with gold-foil pickups and flatwound strings - or something like my ’60s Rickenbaker 360/12 to help change the mood on a session. Or, sometimes, I’d just play my white Gibson Custom Shop Les Paul with nickel hardware and a Bigsby. David dubbed it the “Liberace Guitar.”

Working with David on guitar parts was a very dynamic thing. Sometimes he would have the riff, but he’d hand it to you to develop it. The insistent riff in “Love Is Lost,” for example, is a David riff played by me. The kind of “Peter Green” lead lines are played through a rig David and Tony [Visconti] put together from a photo of Mick Ronson’s setup back in the day. David had found a Ronno Bender pedal - a copy of the old Tone Bender Mick used - and they sourced a Marshal head and a huge 8x10 Marshall cab. I had to stand well back from that rig, and even then it would fry your eyeballs.

Mostly, David would just want you to come up with your own parts, and if he liked where you were going, he would be really encouraging. He loved to see it all take shape quickly, right there and then. “The Stars (Are Out Tonight)” is a good example of a guitar part that was pretty much my first instinct back at the demo stage, and I went on to develop it around his evolving vocals. It was always a treat to do some ambient things around his voice. I would try to find the key harmonic sense of the piece, and then build some loops and lines using an EBow or a volume pedal. I would normally use a combination of distortion, delay, and pitch shifting, and find the right sonic space for it all to exist in the track. These soundscapes would range from dark and ominous to celestial and spatial, and it was extra special to do them whenever David Torn was also on the session. After a while, it got to be confusing as to who was playing what, but what a glorious racket!

When I worked with Earl Slick, David would call us “bookends,” referring to our disparate styles. But he loved the two-guitar thing, and he would encourage us to go all the way. Slick is a fantastic old-school lead-guitar player, and that left me free to be spacious and ambient.

I think David loved the guitar and understood its complexity. He was not afraid to put it front and center, and there was no better place to be a guitar player, but by David’s side [BREAK]

“The Songs Dictated Which Approach Would Work Best”

By Ben Monder

Bowie didn’t really have any gear at the studio - except for one electric guitar and one acoustic. I used the acoustic - I think it was a Yamaha - on “Dollar Days.” I know he played those bizarre “shrapnel” guitars on “Lazarus,” but I don’t know what he used to get that great sound. He mainly sang with us in the live room, which really helped the energy of the performances.