“The Guitar Is an Endless Exploration”: Acoustic Legend Peter Rowan Looks Back on a Lifetime in Music

The Americana treasure connects bluegrass luminaries from Bill Monroe, Jerry Garcia and Tony Rice to Billy Strings and Molly Tuttle, both of whom join him on his new album, ‘Calling You From My Mountain’

Peter Rowan’s 60-year career weaves like a thread through the vast bluegrass tapestry, from its traditional roots through the progressive movement and onto the modern landscape.

Rowan has never been a flashy player. He’s a subtle guitar hero, renowned for his artistic rhythm accompaniment full of meaningful bass runs and purposeful passing chords, setting the stage for his signature vocals and a lengthy list of virtuosic soloists.

Equally adept as a flatpicker or fingerpicker, Rowan has probably played alongside as many all-time acoustic greats on every conceivable instrument as anyone who’s ever donned a guitar.

The iconic list includes Bill Monroe’s mandolin in the Bluegrass Boys, Jerry Douglas’s Dobro, Tony Rice’s dreadnought, and Jerry Garcia’s banjo in the extraordinarily popular Old & In the Way, which in the mid ’70s also included mandolin master David Grisman, fiddler Vassar Clements and string bassist John Kahn.

Old & In the Way made Rowan a star on the jam-band scene, and recently he’s been celebrating it on tour, backed by Railroad Earth. That stint saw him present a Grandstand Stage performance at the High Sierra Music Festival over Independence Day weekend.

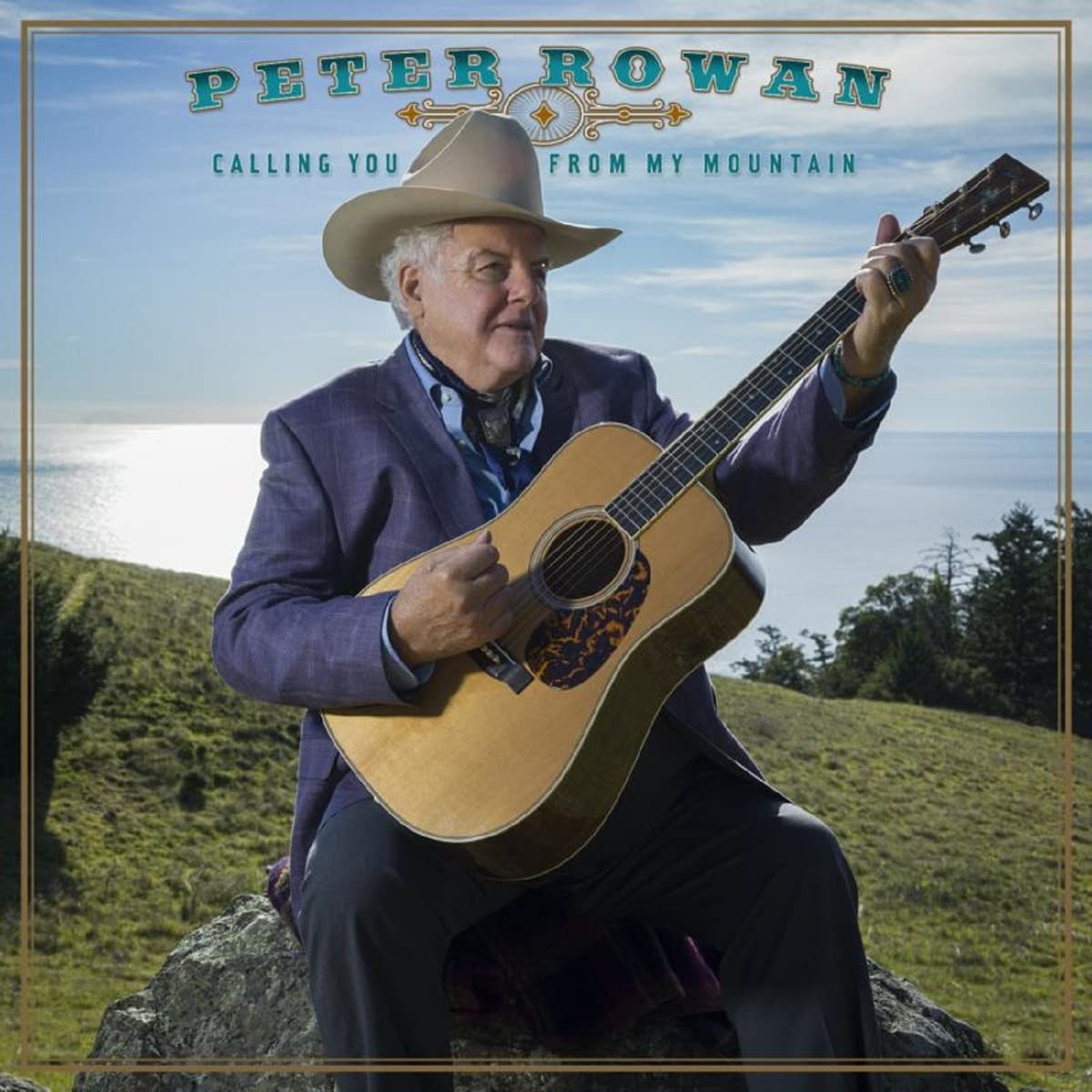

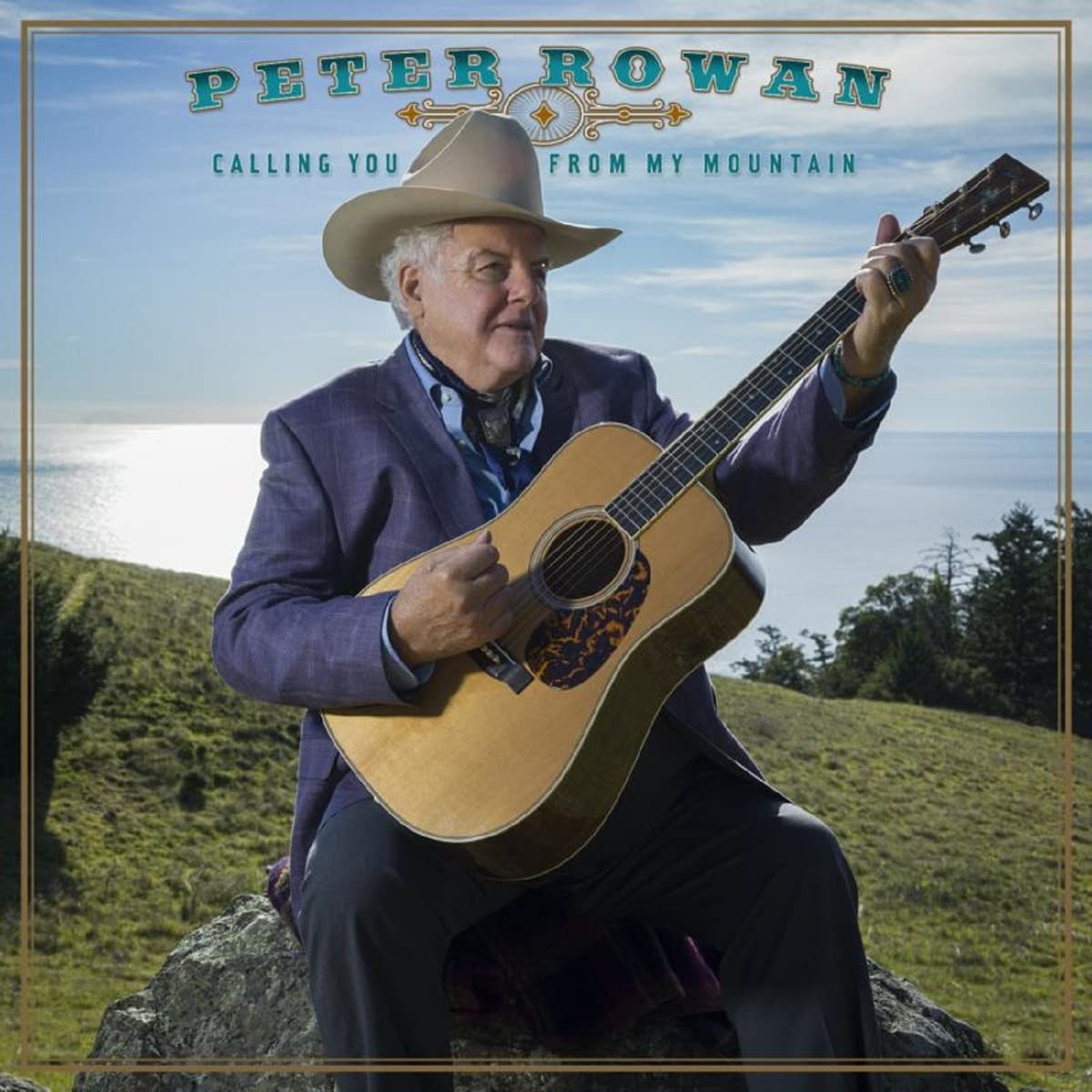

Rowan is such a bona fide Americana treasure, he was actually born on the Fourth of July. The 80-year-old is still sharp as a tack and cutting tracks with his tight bluegrass quintet. Rowan’s new album, Calling You From My Mountain (Rebel), is a deep mix of covers and originals, and it features the current prince and princess of bluegrass, Billy Strings and Molly Tuttle, on a total of four lovely and diverse songs.

Rowan also continues to tour with his electrified bluegrass ensemble, Big Twang Theory, and its country-fried Texas cousin, the Free Mexican Airforce, as well as perform solo acoustic.

What keeps you coming back to the guitar after so many years and miles?

The guitar is an endless exploration of its own language, everything from flamenco to Hawaiian slack key to the blues.

I first got interested in Hawaiian music because my uncle taught me a few songs on the ukulele when I was about five years old.

The tune that has jogged my imagination for years is “Bye Bye Blackbird.” I’ve never really settled on a definitive version, but that song influenced the way I hear passing chords. Libba [Elizabeth] Cotten, who wrote “Freight Train,” was a huge influence as well.

I started out by strumming in a Buddy Holly kind of style on a Telecaster with my rockabilly band, the Cupids, but when I was about 15 and heard Libba Cotten, I was touched by her lyrical fingerpicking and wonderful songs.

When I was about 15 and heard Libba Cotten, I was touched by her lyrical fingerpicking and wonderful songs

Peter Rowan

I begged my father for a Martin, and he bought me an 0-17. That enabled me to get going as an acoustic fingerpicker.

Lightnin’ Hopkins was a tremendous fingerpicker, and everything changed for me when I heard him.

I also studied the music of Lead Belly, and I cover his “Penitentiary Blues” on my new album. But back then I realized that I didn’t have the life experience to be a blues man.

I used to go to a record store in Harvard Square [in Cambridge, Massachusetts, near where Rowan grew up], where you could listen in a booth. When I put on Bill Monroe’s “In the Pines,” I heard the connection to Lead Belly and the blues, but I felt closer to it culturally, so it seemed my best entry was to adopt a bluegrass approach.

I put aside fingerpicking for a while, found myself a big ol’ Martin and started flatpicking.

By 1963 you were in Bill Monroe’s band. What did he impress upon you?

Bill Monroe impressed upon me the importance of rhythm guitar and leading with bass-note runs. He said that the Black man who taught him to play guitar, Arnold Shultz, could play the prettiest runs of all.

Apart from the hot picking leads that have become so popular, the unique thing about bluegrass guitar is the bass runs. That goes all the way back to people like Eddie Lang [known as the father of jazz guitar], and the way he would lead a bass run into a chord.

The unique thing about bluegrass guitar is the bass runs. That goes all the way back to people like Eddie Lang

Peter Rowan

That’s what bluegrass does in the traditional sense, from the style I play right up to Billy Strings. The beauty is in the way it lifts from the bass run into a chord or an arpeggiated type of solo passage.

I spent so many years playing rhythm guitar that bass runs became a big thing for me, and it’s still a wonderful exploration.

Where are you at as a rhythm guitar player now?

I’ve gone back to playing with my fingers, even when doing bluegrass. I practice flatpicking all the time, but in order to keep the continuity between the blues and Hawaiian music and fingerpicking, I’ve gone back to the way that Carter Stanley and Lester Flatt played bluegrass rhythm guitar, which is with a thumbpick and one or two fingerpicks.

That way I can play “Freight Train” as I do in the middle of “Panama Red” [Rowan’s signature song] and have all the worlds of guitar at my fingertips.

What guitars are under your fingertips the most?

The guitar I played on the new album that’s featured on the cover was made for me by Casey Cochran. It’s a dreadnought in Style 28 made out of koa for that sweet, Hawaiian sound.

I write a lot of songs on my old ’37 sunburst [Martin] 000-28 that I got years ago in a series of trades. That’s the most intimate guitar with the most beautiful sound. I also inherited Charles Sawtelle’s 1937 D-18 [the Hot Rize Martin dreadnought].

Preston Thompson Guitars is currently building a commemorative model for me as sort of a lifetime achievement award for my longstanding relationship with them. It’s a troubadour model 0000-28 with all sorts of inlays of mantric syllables and Buddhist designs.

I was actually the first person to buy a triple 0 from Preston, and Charles Sawtelle set that up. When Preston got into making guitars, he based his first two models on Charles Sawtelle’s vintage Martins.

Preston made a triple 0 in style 42, and the other was a dreadnought. I still have the triple 0 that I bought and the dreadnought in Style 28 that Preston gave to me.

The main acoustic I use on the road is a Martin D-18GE Golden Era, which is a single luthier guitar made about a dozen yeas ago. Man, its sound has come in beautifully! Martin has perfected the D-18 as a kind of all-accomplishing instrument. You can really fingerpick it, and it’s great for [flatpicking] bluegrass.

How has your approach evolved?

My way of thinking about bluegrass guitar now is “light touch.” Let the instrument speak, rather than bearing down on it hard, like when I was with Bill Monroe. He simply wanted such solid rhythm that there was only one way to go in my mind at the time. And every time I’d lighten up, he’d look askance, you know?

Let the instrument speak, rather than bearing down on it hard

Peter Rowan

But now I find that it’s easier to sing using the thumbpick and the fingerpick. There’s no pressure on my arm to move, so I can sort of caress the strings with my fingers.

Fingerpicking is basically just a downward stroke on the thumb and a backwards strum on the forefinger, which is interesting because that backwards stroke is a flamenco technique called a rasgueado.

It’s the second half of a motion that starts with a downward strum and then goes backward from the high strings to the low strings.

I still study flamenco music with my buddy Carlos Lomas, in Santa Fe. I appreciate playing the guitar with a more delicate touch to allow the singing to come forth a little more.

Can you speak to Tony Rice’s touch?

A normal person would make every string buzz on his guitar, but Tony’s touch was so incredibly light that it was really beautiful.

And if you listen to Tony’s music, you’ll realize that he didn’t try to take a lot of extensive solos when he was singing. It was when he experienced some throat problems that his guitar playing came to the fore, and he explored some unusual tonalities.

How did it feel to have him accompany you?

It’s a subtlety, but his accompaniment guitar is inspiring, because his use of suspensions and passing chords is so beautiful. We only scratched the surface, because the pressures of touring kind of limit what you can do.

So much is possible on the guitar

Peter Rowan

If I had those days to live over, I’d probably use more open tunings, because of the tonal possibilities. We managed a few. There’s one called “Shirt Off My Back,” which is in open G and played in the key of D.

So much is possible on the guitar, and my love right now is trying to tie those runs in with the passing chords in emotional ways, not just playing them in a slick way.

“Uncle Pen” is a classic example. I play that song on almost every bluegrass set because it settles us into a traditional thing, and that’s my love. On the original record, Jimmy Martin used a dead-stringed Gibson to play that run, and yet it’s the definitive statement of the G run pattern. But it’s still tricky. It’s not just a straight-ahead thing at all, and you get so nervous that it’s easy to make a mistake.

Everybody knows the mistake “Uncle Pen” guitar run, when you land on the B string instead of the G. [laughs] It’s a classic joke among guitar players, because it’s happened to everybody.

What’s so magical about the music of Old & In the Way that it still resonates to such a broad audience to this day?

Jerry Garcia is immortal, and it carries the weight of his spiritual intent. In spite of mortality, the spiritual intent is immortal, and that’s pretty much all there is to latch onto.

Jerry Garcia is immortal

Peter Rowan

How did you come to play his herringbone 1943 Martin D-28?

He had that guitar at his house when we were getting together. I only had a triple 0 at the time, the same ’37 that I have now. He brought out his dreadnought and said, “Hey, do you want to play this one, man?” I did because it’s an unmistakable guitar with a great sound, and that’s the one on all of the Old & In the Way stuff.

When I got to play that guitar [through the Grateful Guitars Foundation] at Terrapin Crossroads a few months ago, I was reunited with that lively, resonant sound.

A week later I was in Nashville, and Billy Strings was in the studio with me. He had just bought a vintage D-28 from the same time period, and the two-toned Brazilian rosewood is exactly the same as the back and sides on Jerry’s guitar.

They’re only a few serial numbers apart, so the wood that you hear on my record from Billy Strings is from the same woodpile as Jerry Garcia’s D-28.

Billy Strings is seemingly everywhere these days. What do you appreciate most about his playing?

I like how he plays for emotion, not for flash. I didn’t want him for just his extraordinary solo capabilities. We played the tunes a couple of times and he played fabulous rhythm/lead guitar. He put a couple of Tony Rice’s patterns in his runs and fills to honor him.

Emotion is what strikes me about Molly Tuttle

Peter Rowan

I love the feeling he put into his playing on “A Winning Hand,” which is like an Irish ballad. Billy took a natural approach and simply played the music, which is what I wanted.

How about Molly Tuttle’s contribution?

Emotion is what strikes me about Molly Tuttle as well. When she came into the studio and sang the title cut, she didn’t try to sing it with a bluegrass style; she sang with something that is the essence of Molly Tuttle, which is tremendously moving to me.

I’m always struck by her voice. It’s tender and vulnerable, not clichéd at all. She also sang a wonderful part on “The Red, the White, and the Blue” and she played lovely clawhammer banjo on that too.

I feel so grateful to still be playing bluegrass for such a broad audience with my band. We’re playing the music as straightforward as we can, and that’s all we were doing with Old & In the Way. We’d practice every night, just for the joy of doing it.

The idea of going out and playing came afterward. This band has that same joy. We’re not some fabrication of somebody’s imagination, with a bunch of tour posters and merchandise. We’re just a bluegrass band, and that’s all it’s ever been.

Order Peter Rowan's Calling You From My Mountain here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jimmy Leslie has been Frets editor since 2016. See many Guitar Player- and Frets-related videos on his YouTube channel, and learn about his acoustic/electric rock group at spirithustler.com.

"This 'Bohemian Rhapsody' will be hard to beat in the years to come! I'm awestruck.” Brian May makes a surprise appearance at Coachella to perform Queen's hit with Benson Boone

“We’re Liverpool boys, and they say Liverpool is the capital of Ireland.” Paul McCartney explains how the Beatles introduced harmonized guitar leads to rock and roll with one remarkable song