“The guitar allows me to switch my brain off from trying to understand the music... The mistakes make it interesting.” Crowded House's Neil Finn on his trial-and-error approach to playing and songwriting

Four decades in with Crowded House’s ever-changing lineup, Finn remains committed to exploring possibilities

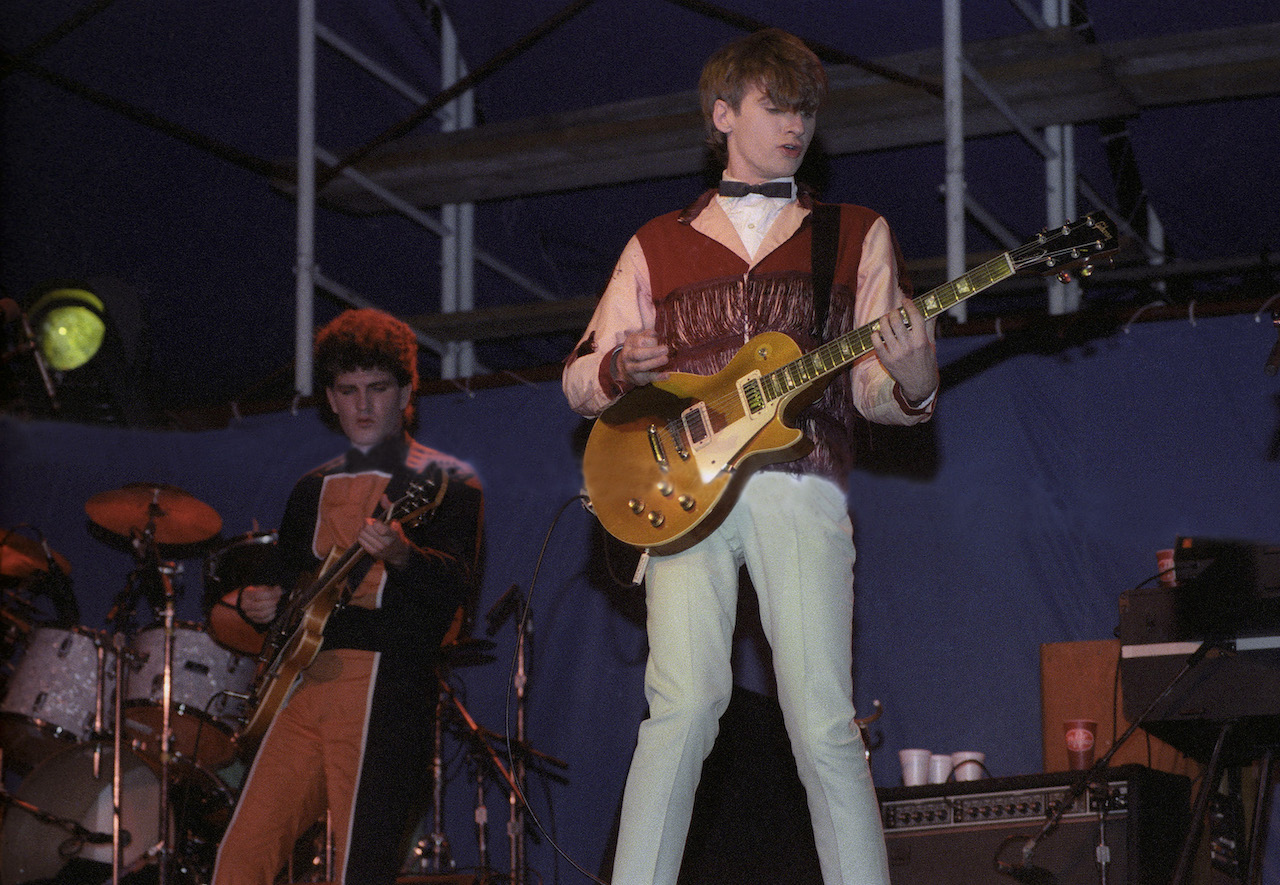

Crowded House’s return five years ago was certainly a welcome one. The Australian-formed group had been dormant since 2016, when it played four shows at the Sydney Opera House and was inducted into the Australian Recording Industry Association’s (ARIA) Hall of Fame. So frontman and co-founder Neil Finn’s announcement of resumption and a new lineup – with original bassist Nick Seymour, original producer Mitchell Froom on keyboards, and Finn’s sons Liam and Elroy on guitar and drums, respectively – was greeted with great anticipation, even if the pandemic delayed the group’s return to the stage.

“It does feel like it’s got a really good future, because everyone is super excited,” Finn enthused during the spring of 2021, when the new Crowded House released Dreamers Are Waiting, the band’s first new album in 11 years. “We want to push it. We’ve got five people equally committed to exploring what it could be.”

That he meant business is proven by the new Gravity Stairs (Lester/BMG), Crowded House’s eighth studio album overall. Produced by the band with longtime engineer Steven Schram, its 11 tracks are brimming with the particular musical magic that Finn, Seymour and drummer Paul Hester – who committed suicide in 2005 at the age of 46 – began making in 1985 as the Mullanes, before Capitol Records insisted on a name change.

The melodies are, as is Crowded House’s wont, rich and memorable, usually by the second chorus. The soundscape is intricately orchestrated with nuanced layers of guitars, Froom’s Hammond B-3 accents, and lushly executed vocal harmonies that have always been Crowded House trademarks but now boast a familial potency thanks to having three Finns onboard.

The House, of course, has a strong foundation. Construction began in New Zealand, where Finn grew up as the youngest of four children. Brother Tim’s musical aspirations rubbed off on Neil, who started playing guitar at age eight, after Tim went off to boarding school in Auckland. They wound up playing together in the band Split Enz when Tim invited Neil to join during 1976 to replace co-founder Phil Judd. Neil quickly became a dominant force, sharing lead vocal duties with Tim and becoming the group’s primary songwriter with tunes like the worldwide hit "I Got You."

Finn formed the Mullanes in 1984 with Split Enz drummer Hester and Seymour – the younger brother of Hunters & Collectors’ Mark Seymour – as well as another guitarist, Craig Hooper, who left just before Crowded House recorded its self-titled 1986 debut album. The band was a hit out of the box – Crowded House was number one and six-times Platinum in Australia, and also a million-seller in America. The singles "Don’t Dream It’s Over" and "Something So Strong" were worldwide hits, and even though the set represented Crowded House’s commercial peak, it established a standard of quality that’s kept people paying attention ever since.

Along the way, Finn has guided the band through an array of sonic and stylistic adventures, deflecting expectations whether it was the artistic moodiness of 1988’s sophomore release Temple of Low Men or the sophisticated constructs on 1991’s Woodface (home of other enduring favorites "Weather With You" and "Fall at Your Feet") and 1993’s Together Alone. The group took a couple of hiatuses along the way and made some membership changes – Tim Finn and Supertramp adjunct Mark Hart both logged time in the lineup, and Liam and Elroy Finn made their first appearances as guests on 2007’s Time on Earth and served as touring members afterward.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Dad, meanwhile, has released four solo albums plus one collaboration with Liam (Lightsleeper, in 2018) and another with Paul Kelly (Goin’ Your Way, five years earlier). The elder Finn and his wife, Sharon, also put together a side project called Pajama Club in which he plays drums and she plays bass in addition to their other instruments.

Crowded House’s 2019 reformation was precipitated by Neil Finn’s tenure with Fleetwood Mac – along with Mike Campbell from Tom Petty’s Heartbreakers – during its final tour, in 2018–2019. Afterward, Finn recalls, “I was quite keen to turn around and do something creative, in the studio. I realized I had my own good band – maybe slightly more humble in terms of success, but equally profound in my mind. The day after the tour finished, Crowded House were in rehearsal in Los Angeles. It was fantastic. That energy went right into that [rehearsal] and making new songs.”

That, of course, yielded Dreamers Are Waiting – which had to be finished remotely during the pandemic – and the tour that followed. And now we have Gravity Stairs and Neil Finn at home in New Zealand with “the little toys that are around me” – a piano, a microphone, a Mellotron and recording devices. “I bring a guitar and bass in here occasionally, and I just make things from scratch,” he says. Gravity Stairs is only the latest of what he expects to be a lot of things that will be made by the current Crowded House, which he doesn’t dream will be over any time soon.

Was there any doubt five years ago that you were resuming Crowded House as a going concern?

Not really. I mean, we were awash with possibility at the moment, and having done a lot of touring, we were feeling like we were just getting started. There’s nothing like playing a lot of shows to make a band kick up a few gears and trust each other and just relish the prospect of what might be possible.

Did it feel like yet another new era for Crowded House?

It is, yeah. But it’s got a strange feeling of also returning to the source because of the presence of Mitchell Froom. And even Liam and Elroy, who bring with them a fresh energy and vigor, they have a life experience from right at the beginning, in the tour bus, hanging out with the band, and at sound checks. Liam was doing guitar changes for me at the age of three. Elroy, on the other hand, showed more interest in turning off the main power for the lights 30 seconds before we were to go onstage — he actually did that. So it’s new, but familiar, and the ethos and the humor and the aesthetic of Crowded House is deeply ingrained in all of us.

What’s the greatest difference you hear in this version of the band?

The presence of these two guys, Liam and Elroy. They’ve had a lot of experience as songwriters, arrangers, performers. I hear combinations in what they bring of things they’ve done on their own and their experience growing up with [Crowded House]. Elroy’s drumming is really impressive, and onstage he’s come into his own as a very dynamic drummer with a beautiful, steady feel as well. He learned a lot of the ways he drums from Paul Hester, both directly and indirectly.

And Liam will have ideas for subverting the sonicscape with pedals that wouldn’t occur to me, but they’re part of his thing. They’ve added quite a lot to it.

What kind of evolution do you hear in the band from Dreamers Are Waiting to Gravity Stairs?

That’s a tricky question, because music just pops out in a very mysterious way all along, really. I think what bands bring is a sense of dimension that lets the light into the arrangement in a way you can’t do on your own, ’cause anything you come up with is designed to paper over the cracks of your ideas and not expose them; whereas anything a band does is to sort of open them up to new possibilities. So you sit there and go, Okay, I wouldn’t have done that, but I kinda like it, and it’s letting a bit more light into my idea, so...

It’s hard to point to specific tunes or a particular song, but there are some compositions Liam and Elroy have been involved with that are suggestive of a new direction. The youngsters – the comparative youngsters — are informing the process in a really cool way on songs like "Blurry Grass" and "Thirsty" and "The Howl." There’s some indications of new directions there.

So what are those things you hear on Gravity Stairs that feel new?

Like I said, it’s really hard to be more specific because my whole experience of music is very mysterious. I don’t sit down, ever, really, and go, Okay, I’m gonna write a song today about this thing and I’ve got this feeling and I want it to be like an R&B song, or I want it to be like an English ’60s kind of song. I never approach music like that. I always start with my headphones on — I start to build atmospheres and make things up from scratch. It’s not a conscious process. I really rely on my subconscious delivering, and then I’ll follow that thread, whatever it is.

How do you tend to start that creative process?

On piano, guitars... whatever. I often start with a drum machine or a loop or something that’ll just keep me concentrating. It’s like you’re trying to sell yourself on the idea before you’ve even had it by creating an atmosphere in which to operate.

And I pore over old jams. Like, I’ll jam on the piano for half an hour, or a guitar, and I’ll go through and find something. It may only be for 10 seconds, but it pricks my ear up and I go, Okay, I’ll separate that and put it into a new context and maybe make a loop out of it or add a few things to it and just try not to be too conscious or judgmental while I’m doing that. I’ll make several demos, and at some point I’ll sing over it, and at that point I’m on the trail of a song and I’ll make a deeper demo.

What on Gravity Stairs was drawn from things that you’ve had around for awhile?

I’m not really interested in defining things on guitar as much as allowing notes that ring over

Well, they’ve all been in demo form at some point or another. For instance, the last track on the record, "Night Song," is actually quite an unusual song in that it slips between time signatures and things. But the whole thing came from a jam I had on a Prophet synthesizer. I don’t know how to play synthesizer, but I found a sound on it that was really fun. It had overtones and was suggestive of different chords, and I just jammed over it for a half hour and actually made a 20-minute piece of music from it by adding guitars and piano before I even tried to make it into a song.

And that delivered what is the closing track on the record. If you use headphones you’ll hear in the background a woozy, curly little synthesizer sound that was the original impetus for the song.

Once you have all that done, is there a methodology for how you layer in and orchestrate the guitars, which is a real hallmark of the Crowded House sound?

It’s often the next stage after I’ve done a jam and I’ve identified some things that are quite interesting or cool. My normal thing on guitar is to try and find blurriness and add that to whatever I’m jamming on, and through that to get an unusual combination of chords or something that suggests a melody. I really try and keep it in the blurry, abstract zone for as long as I can in those early stages so I allow possibilities to exist and just put myself into the ether somewhere so I can latch on to something.

I’m not really interested in defining things on guitar as much as allowing notes that ring over. I’ll find a little recurring pattern that’ll ring over the jam, and that’ll give me a little extra atmosphere to go and try vocals. It’s a textural device in some way; it becomes melodic sometimes, but the guitar allows me to switch my brain off from trying to understand the music. I like being able to not understand it.

Does that explain why we tend to hear so many extended chords from you – the major 7ths and 9ths?

Yeah, I like that. Sometimes I think, I’ve got to make some definitions here and actually play straight chords in order to make the songs speak, and that often comes later on. I can listen to those blurry chords forever, but it gets to a point where I don’t know if I’m gonna take everybody with me. My wife sometimes comes in and she listens to what I’m doing, and you can tell it’s sort of not apparent enough to her, and I take that as a sign. So then I’ll strip away some of those extra notes and try to get the chords into a more understandable shape, and often that leads to a stripping down or an economy of thought that helps the listener, I think.

When you do find a place for a lead line, is that more organic than academic or cerebral?

Pretty much, yeah. Playing lead guitar is a very interesting and mysterious process. I don’t do many leads. I do a few onstage and they’re always a little different every night, but I have a certain rough form that I might try to follow. It’s just my way of doing things. In an ideal world I’d play it super melodic and be in complete control and have my brain tell me what the melody is and have my fingers obey. But usually my fingers don’t obey. I rationalize that by saying the mistakes make it interesting and the lack of learning something allows lovely possibilities to exist.

But, like I say, that’s just my way. I have been asked sometimes what advice I would give guitar players learning their instrument, and I have staked my rationale on the idea that to learn someone else’s guitar solo at any point is probably not going to end very well, because you’re gonna end up sounding like an imitation of somebody. You’re better off to have it in your head, “Oh, I’m gonna slam it like Jimmy Page here,” and get it wrong, and by getting it wrong your personality comes through. Personality is a hard thing to come by in music these days, and it’ll be even harder once AI kicks in in a big way.

Are there players you considered influences early on?

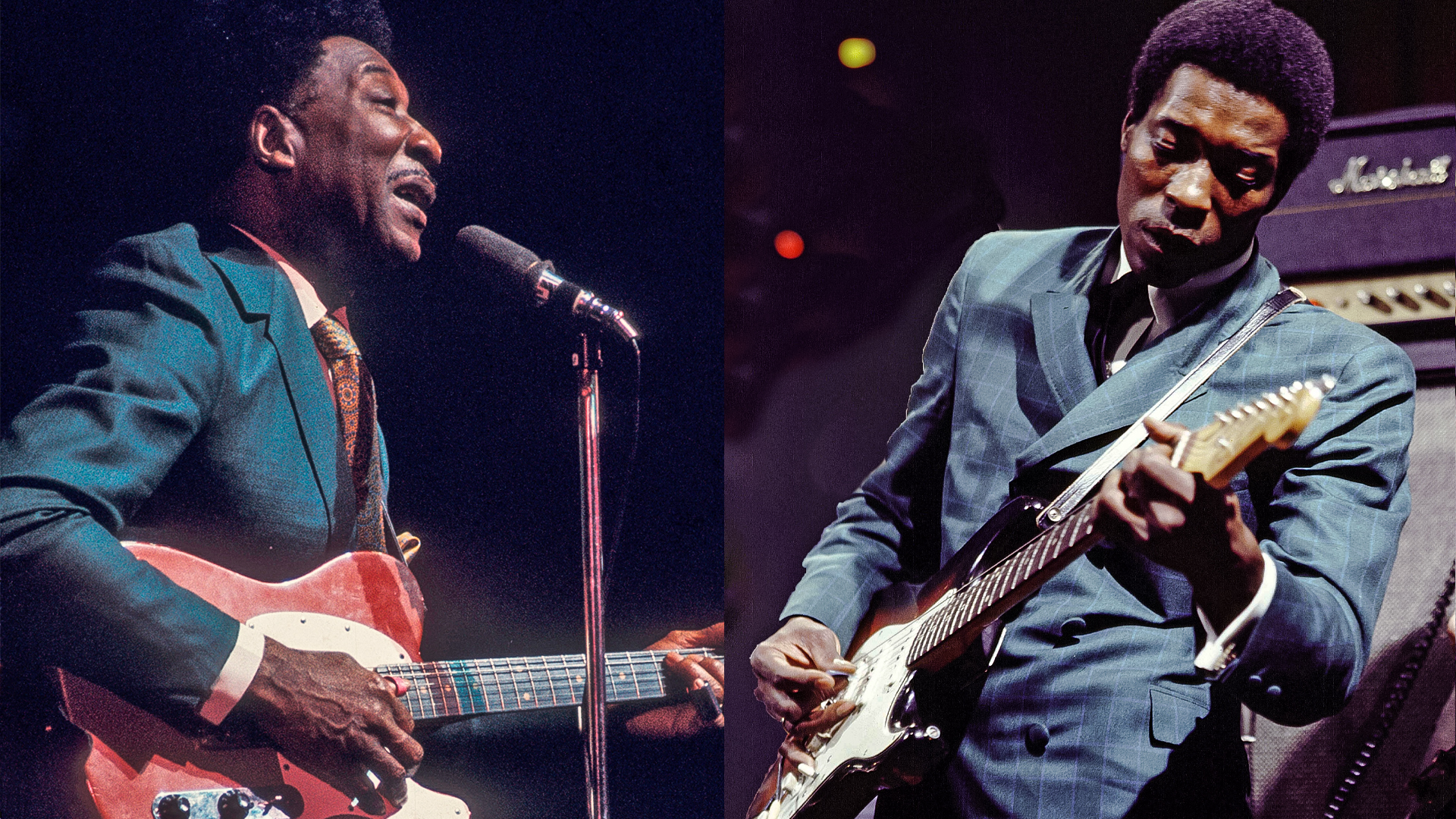

I’ve got guitarists I would hold as absolute geniuses — Hendrix, Jimmy Page, Peter Green, among many others. There’s a lot of guitar players I admire, but I’ve never sat down and tried to learn one of their solos. I can’t even imagine doing it, but I have definitely at times gone, Oh, that sounds a bit like what Peter Green might’ve done, and followed that thread. And then got it wrong.

What’s changed most about you as a player now?

I think I’m more tuned into finding accidents in the way I play. Back in those days, I was actually trying to play properly and just making accidents. But now I’m more tuned into the interdimensional possibilities of making mistakes. When I’m talking about listening in jams, I’m almost usually going for a bar where I don’t quite hit what I hoped to hit, and it becomes more interesting. So I guess I’m listening more — I’m finer-tuned to listening than I used to be. I can follow interesting threads more than I used to, I think.

Who inspired your writing in any way?

In my early years of writing songs, it was obviously the Beatles, but also Neil Young, Carole King, Elton John, James Taylor – those were the kinds of things I was listening to, and learning how to think about songs. David Bowie, very much — early Hunky Dory. That was when I was about 14. They were all on high rotation, those things. And Split Enz, with my brother, they were writing these magical songs I was influenced by as well.

Do all of those sources have something in common that you recognize as part of your writing, or your philosophy of writing?

I was a big fan of melancholy. Songs with yearning. I liked the odd upbeat rock tune as well, but I more was particularly inspired by songs that had a little melancholy attached to them, but perhaps a little redemption in the chorus. That was common to all the people I’ve mentioned, I think. Take for instance Carole King, "It’s Too Late." It’s a real upbeat song but it’s a bad breakup song, so it’s that kind of a counterpoint of introducing some joy or redemption into a sad topic that’s always been of interest to me.

How does that manifest in your songs now?

Somebody said the other day that our early albums were exuberant and these [recent albums] feel more measured, which I sort of disagreed with. But when I thought about it later, I thought, Well, when you’re 25 there’s a sort of exuberance that you exude.

But I much prefer the way I sound now as a singer, in terms of being able to be more nuanced about the things I’m delivering. I think it’s a better form at the moment, but it’s related to my age and the amount of experience I’ve had. I can’t really try to be that guy that was 25 years old and bouncing around all the time.

How is the experience of being in a band with your sons? It’s one thing to be in the family business and quite another to be working in “the store.”

Well, it’s a very deep connection now, musically. We obviously have a very deep connection as a family, but having done all these gigs we’ve learned to really trust each other and jam onstage. Initially there might have been some degree of, Oh, I better make sure I don’t upset the apple cart here and let Dad do what he does and support that. But they’re deeply embedded now, and it’s a very complementary situation and a very collaborative situation.

But now there’s a little bit of confidence to sort of take up the lead every now and again, and certainly if I start jamming and free-forming on something, everyone’s just willing to jump in, and that just comes from spending hours together, just understanding the way phrasing should be or where to let notes off and all of that. The familial thing we have is just a beautiful underpinning to everything.

How do you and Liam work together as guitarists?

Liam as a guitar player is becoming extremely important in the sound onstage and takes the audience on some pretty epic adventures I wouldn’t be able to. Even theatrically, throwing his guitar up in the air and catching it. He hasn’t dropped it yet, put it that way. It’s pretty exciting stuff.

What does he do that you wouldn’t?

He’s more interested in effects pedals than I am. He’s got some really good effects pedals and he knows how to use them, and they are genuinely unhinged at times.

But we’re quite complementary. We do some things similarly. He can be melodic, but he’s got a spectacular sense of drama in his guitar playing that suddenly takes the song to a new place. I’m a little bit more of a keeping-the-groove-going and keeping-the-atmosphere-going guitar player, with an occasional flourish. So it’s exciting when we’re learning songs, ’cause it’s sometimes wrong what he’s doing, but it leads him to a really good place.

Crowded House have a 40th anniversary coming up next year. Anything planned for that yet?

We haven’t really made any special plans, no. Anniversaries come quite often, so we should mark it in some form. But, yeah, I’ll get back to you on that. If anybody’s got any ideas, send ’em through.

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.