The Evolution of Hill Country Blues

From Mississippi Fred McDowell to Cedric Burnside, here’s how a new generation is taking the juke joint sound forward

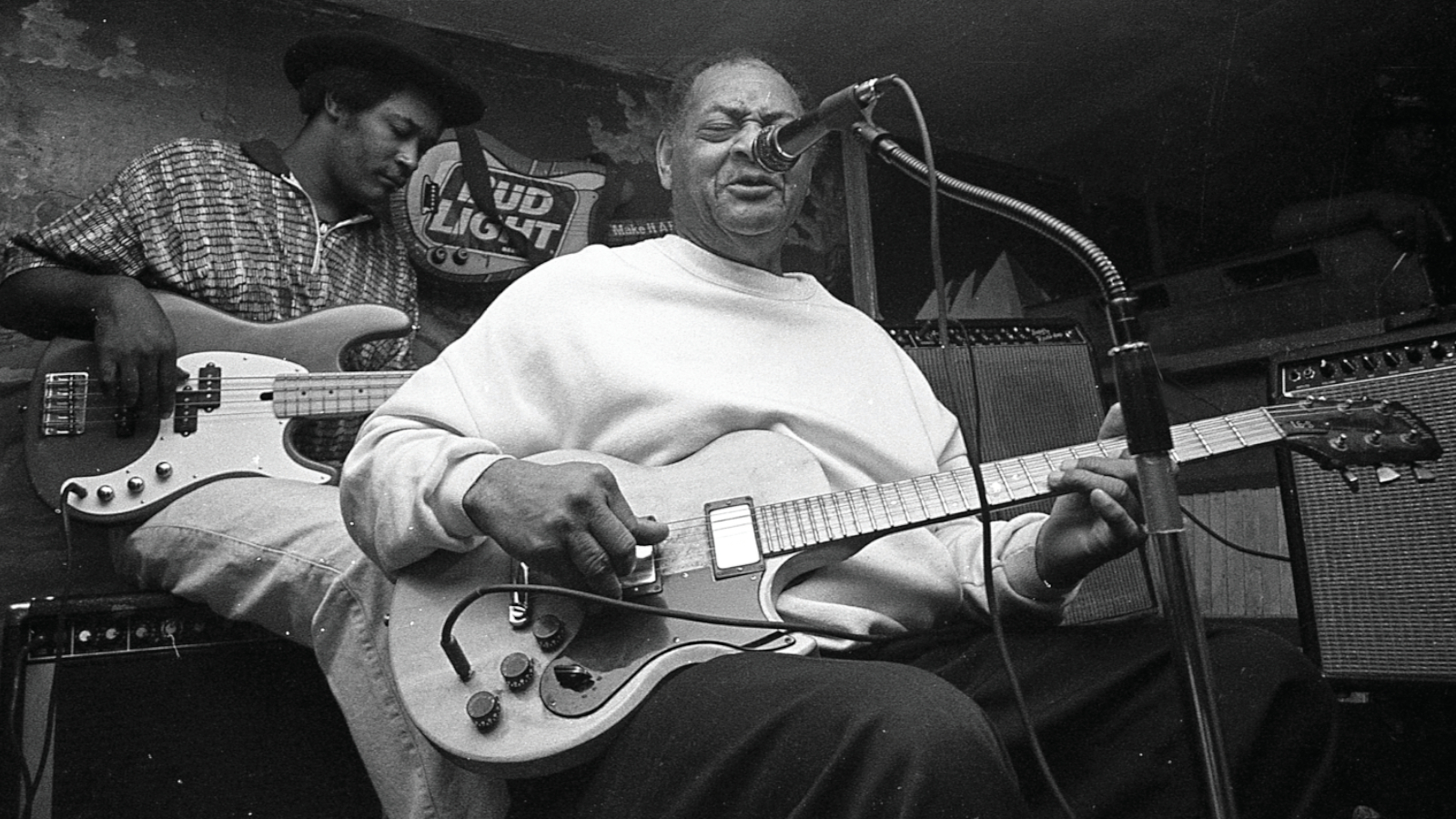

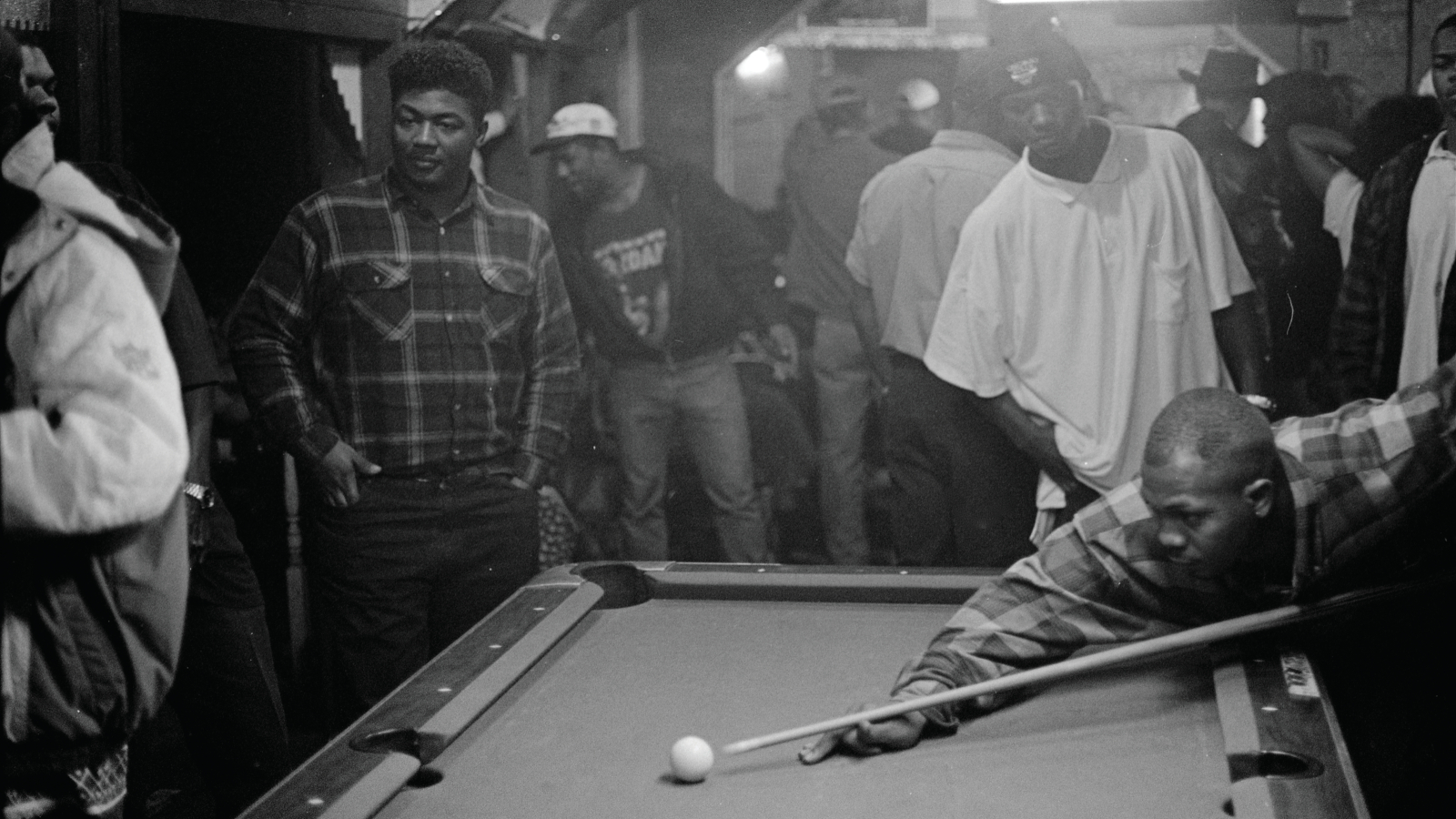

You can’t visit the place where hill country blues, the hypnotic strain of blues that developed in the kudzu-wrapped hills of northern Mississippi, had its 1990s heyday. The elders – Junior Kimbrough and R.L. Burnside, chief among them – are no longer alive. And the club where they performed outside Chulahoma, Mississippi, is long gone.

There has been no greater embodiment of the rural blues that germinated in the hill country than Junior’s Place, the famed juke joint owned by the often-bawdy bluesman Kimbrough.

Like the music played within its walls, it was an unpretentious place, a simple, wood-frame building shielded from the elements by sheets of rusted tin roofing, with a dirt parking lot and frontage along a lonesome state highway.

Kimbrough’s juke had few rules, and most were scrawled onto white paper signs posted outside the door: No drugs or outside booze were allowed into the club, but patrons could buy cold beer from an upright refrigerator, and homemade corn whisky, once they went inside.

The building had been a church and a general store before it became the juke unofficially known as Junior’s Place, ostensibly because it had no formal name.

Sunday was the day to be there, usually, and the music went all night. Of course, it wasn’t the first juke in the area, and it wasn’t the last. But during the ’90s, Junior’s Place hosted countless performances by Kimbrough and Burnside, who often recruited their kids and grandkids to back them on drums, bass and sometimes a second guitar.

By age 10, I was good enough to play in the juke joints

Cedric Burnside

Cedric Burnside, a grandson of R.L., whose 2021 album, I Be Trying, won a Grammy, started playing drums in jukes before he was a teenager.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“By age 10, I was good enough to play in the juke joints,” he says. “Mr. Kimbrough used to give me about five dollars every weekend when I got done playing. I think he gave that to everybody, even the grown folks.”

What Cedric brought to the music was crucial, though. Percussion and rhythm are key to the hill country blues sound. Unencumbered by the strictures of 12-bar Delta blues and I-IV-V chord progressions, Hill country songs can repeat licks and motifs almost until they become trance inducing, propelled by the rhythmic, slide-accented guitar figures.

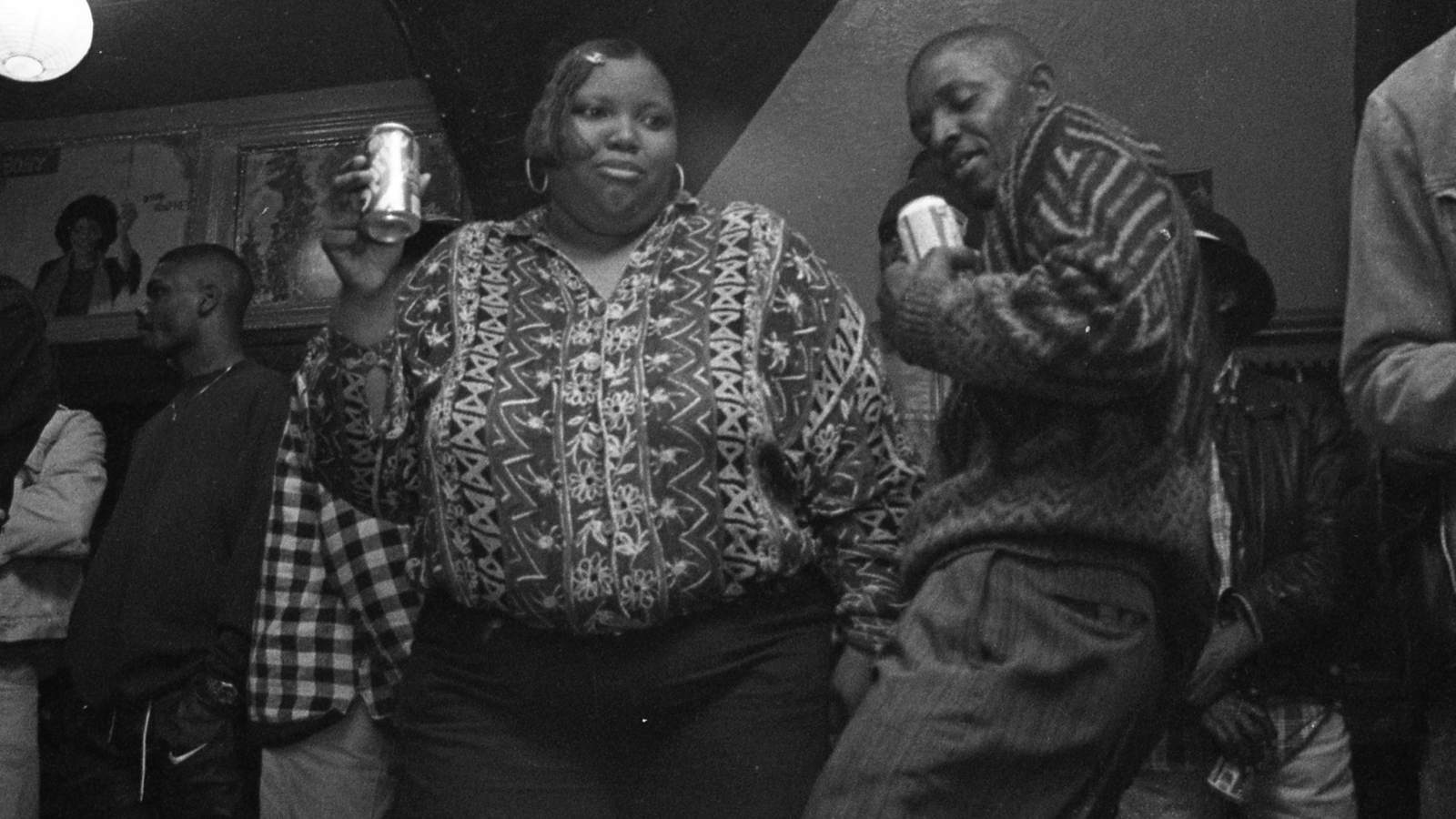

Where Chicago blues polished and electrified the Delta blues, the music in the hill country remained a primal country blues. The full expression usually isn’t a concisely crafted song, except on recordings. In a juke setting, the songs became background for dancing. And in the long tradition of American roots music, and especially blues, lyrics and licks from one song are often mixed into other songs.

While McDowell, Junior and R.L. wrote a lot of their own songs, some, like “John Henry,” were part of the oral tradition.

Luther Dickinson of the North Mississippi Allstars attests to one unspoken but important rule of hill country blues, though. “The main lesson I learned from playing at Junior’s is to never clear the dance floor,” he says. “R.L. could keep a room dancing by himself with his syncopated fingerpicking.”

R.L. [Burnside] could keep a room dancing by himself with his syncopated fingerpicking

Luther Dickinson

Because performances could go from early evening until dawn, Cedric says, “there was a lot of repetition of songs. But also, they played some songs a lot because people had favorites. One was ‘All Night Long’ by Junior Kimbrough. Even though he had several songs, he sometimes played that song four or five times in the same night, ’cause people were requesting it that much.”

The roots of hill country blues are West African, particularly in the focus on rhythm and drums, but also the fife, an instrument played in hill country blues by the late Otha Turner.

Enslaved people in America were forbidden to have drums after their overseers discovered they could be used to communicate with each other. Following the Civil War and Emancipation, though, drums resumed their place in African-American culture and expression. The fife-and-drum tradition is an outgrowth of that.

“The differences in Delta, Chicago and hill country are kind of tough, but it’s real,” says Kenny Brown, who played sideman to both R.L. and Junior for decades, and now leads his own group while also collaborating with artists like the Black Keys.

“And it’s fun music and it’s happy music, most of it, and it’s more concentrated on the groove and the rhythm. A lot of the hill country stuff, I believe, was strongly influenced by the fife-and-drum bands.”

In the early ’90s, two events brought a critical spotlight to this corner of the South. First, the Robert Mugge documentary Deep Blues, narrated by hill country blues champion Robert Palmer, a music writer who penned an authoritative book of the same name in 1982, featured R.L. and other blues artists from the region.

A lot of the hill country stuff, I believe, was strongly influenced by the fife-and-drum bands

Kenny Brown

Then, a fledgling new label in nearby Oxford called Fat Possum Records began a campaign to record the region’s country blues artists. R.L. and Junior were first, with the raw, uncompromising Too Bad Jim and All Night Long, respectively, in 1992.

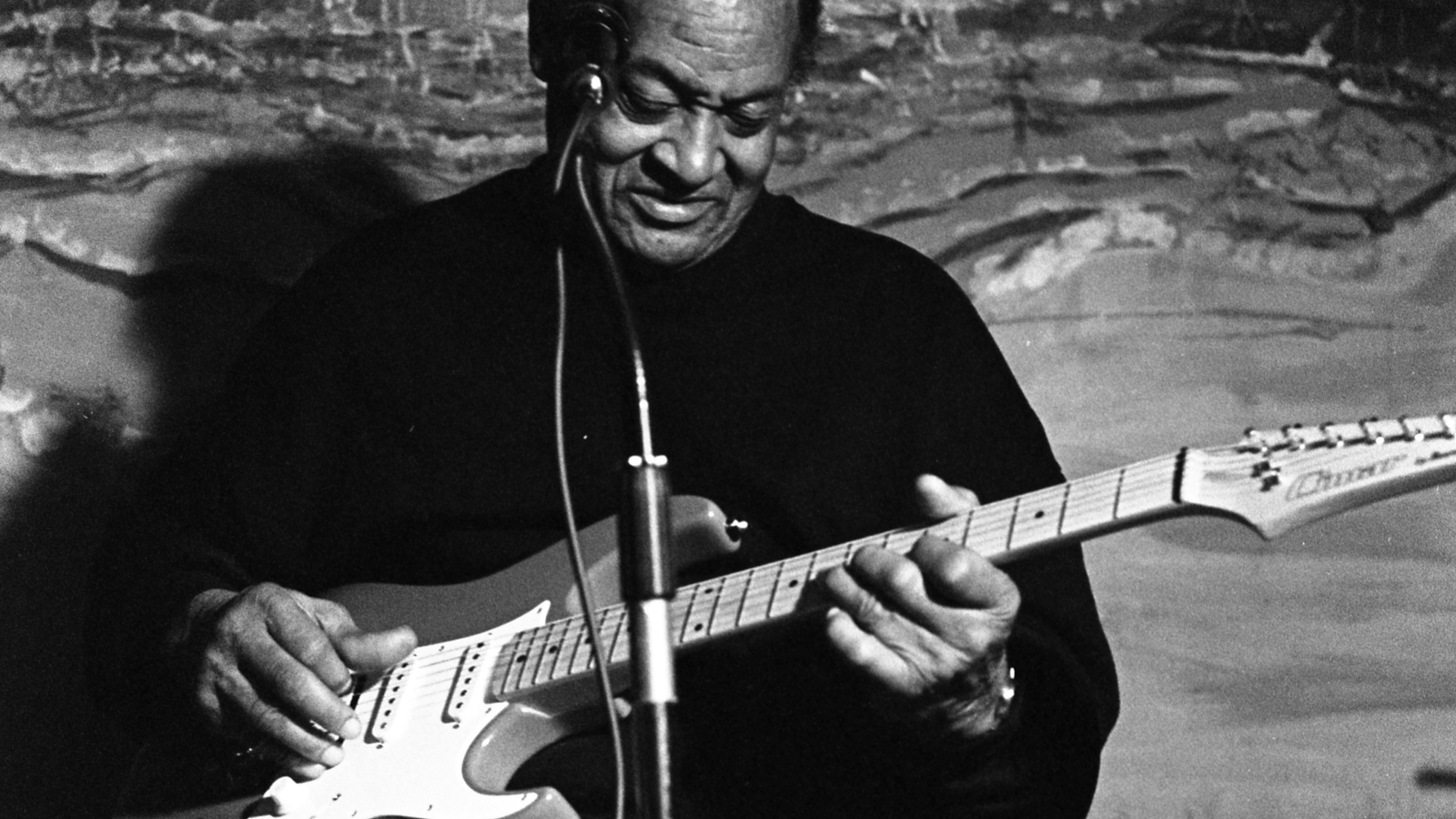

R.L. found a new, young audience in punk, garage and indie-rock circles after opening for Jon Spencer and the Blues Explosion on tour. “When we did this stuff with Jon Spencer, we got to play for younger kids, and they loved it,” Brown says.

“We played a little louder, and I don’t know if it was any faster or not, but that kind of evolved into more of an electric, rocking band than the duo stuff did.”

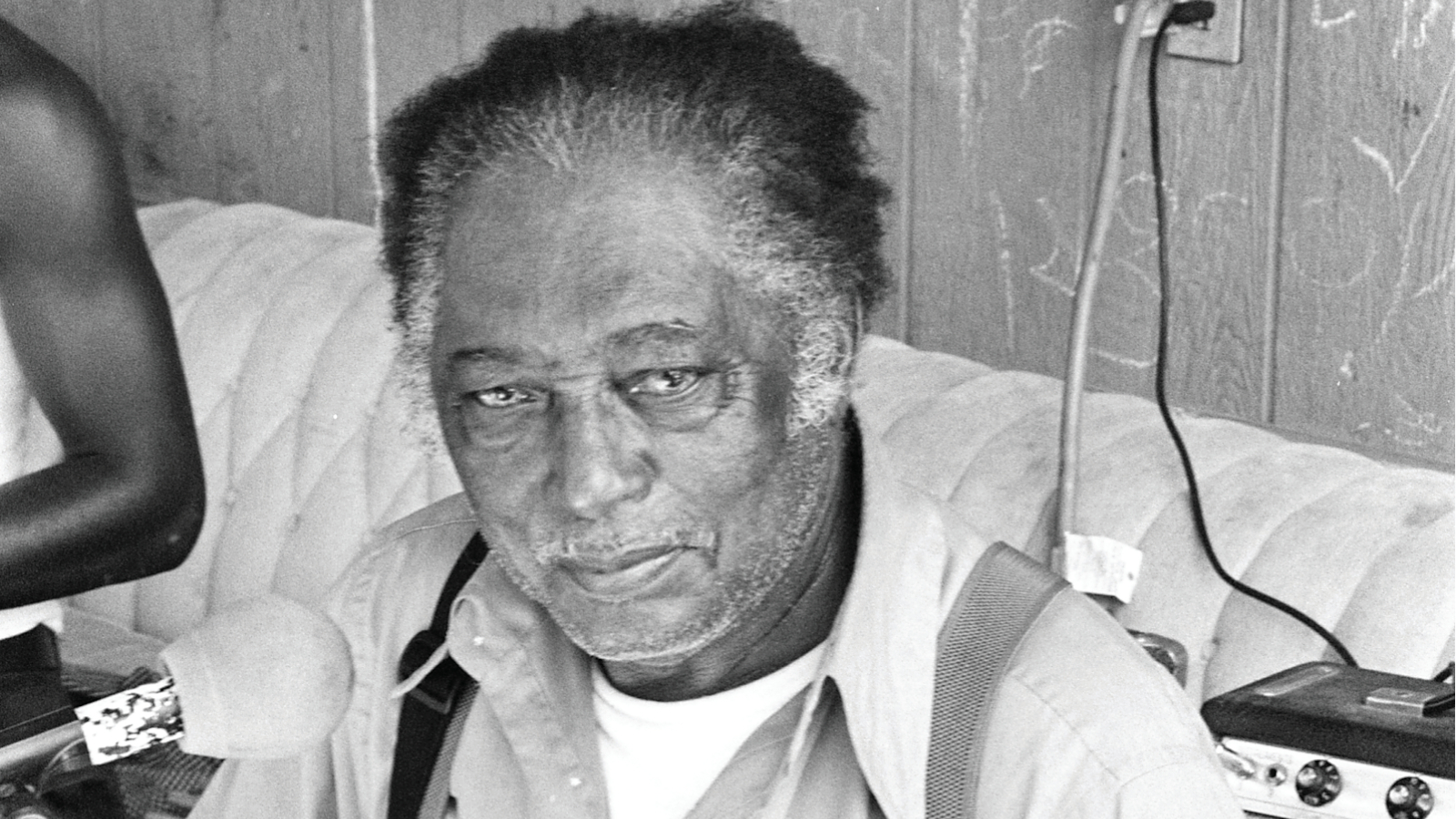

The style of blues that became recognized as hill country in its modern form traces back to Mississippi Fred McDowell, who worked as a farm laborer and played country blues at parties on weekends.

Musicologist Alan Lomax recorded his first sessions in 1959 on one of his trips through the South, but as the folk-blues scene heated up in the mid ’60s, McDowell began to record more. His repertoire combined traditional and gospel songs with his own compositions that became foundational to the hill country canon.

“Wished I Was in Heaven Sitting Down,” from the Lomax recordings, was later recorded by R.L., and “61 Highway,” from McDowell’s 1969 album I Do Not Play No Rock ’n’ Roll, is recognized as a key composition in the genre.

The style of blues that became recognized as hill country in its modern form traces back to Mississippi Fred McDowell

Other signature hill country tunes, like “Drop Down Mama,” “Going Down South” and Bukka White’s “Shake ’Em on Down,” were key songs in McDowell’s sets.

Brown met McDowell at the Memphis Country Blues Festival in 1969 but didn’t get to play with him. He did, however, come to know Johnny Woods, a harmonicist who recorded and performed with McDowell.

“I learned a lot from Johnny about Fred’s playing,” he says. “It took me years to figure out what he was talking about. He’d say, ‘Frail it man, frail it!’ I figured out what he meant: It’s like your thumb and your index finger are going back and forth, and as your thumb’s going down and your finger’s going up, it creates a lot of rhythm.

“R.L. Burnside and I, we both got to doing pretty much that same kind of thing when we were playing together on two guitars, and that created that sound.”

Brown wasn’t the only blues fanatic listening to how McDowell played guitar. Keith Richards, Mick Taylor and the Rolling Stones were inspired enough to record a faithful cover of his song “You Got to Move” on Sticky Fingers in 1971, with Taylor playing the slide licks on a 1954 Fender Telecaster.

Aerosmith delivered their own take on their 2004 blues covers album, Honkin’ on Bobo, setting the tune to a rock and roll arrangement over a Bo Diddley beat.

McDowell’s note placement was very intentional. He used a slide to drive the tunes, but his flourishes often were a series of well-placed notes without flashy tricks like slide-ins, hammer-ons or pull-offs.

One of the most important things McDowell did, other than write and play music, was to teach his neighbor R.L. Burnside how to play blues

One of the most important things McDowell did, other than write and play music, was to teach his neighbor R.L. Burnside how to play blues. Although 22 years his junior, a teenage R.L. latched onto his mentor’s rhythmic style of playing. A few years on, he would accompany McDowell on gigs at house parties and juke joints in the area.

“Him and my Big Daddy were really, really great friends,” Cedric says, using his preferred name for his grandfather. “They shot craps and drank a bunch of moonshine and stuff together.”

Burnside lived in Chicago for a period in the ’50s but soon returned to northern Mississippi. In 1967, George Mitchell recorded him in Coldwater for the Arhoolie label, which helped him get gigs. Like other hill country bluesmen, his music career ebbed and flowed, and he worked on a farm to supplement his income when the gigs weren’t there.

He formed the Sound Machine with his sons and in 1981 put out Sound Machine Groove, a record that reflected the times. Playing electric guitars, the band somehow aligned country blues with danceable funk and soul.

The next time R.L. recorded, though, would be with Brown by his side and Calvin Jackson, his son-in-law, on drums. Titled Too Bad Jim, and released in 1994, it was the first of a six-album studio run before his death in 2005.

The record found a wider audience for the genre, thanks in large part to the intervention of Jon Spencer, who brought R.L. on tour. That led to a creative partnership in the studio, as well. The band backed R.L. on a pair of albums, 1996’s A Ass Pocket of Whiskey and 1997’s Mr. Wizard, which modernized the hill country sound.

R.L. Burnside lived in Chicago for a period in the ’50s but soon returned to northern Mississippi

Brown has vivid memories of moving to north Mississippi in the early ’60s. Across the street from his family’s home, Otha Turner and Fred McDowell would host picnics and play music all weekend. That experience primed his interest for when Mississippi Joe Callicott moved in next door, when Brown was 10 years old.

Callicott had recorded with George Mitchell the same year as R.L., and cut songs for the U.K. label Blue Horizon on a Memphis session that included Furry Lewis. Soon after his arrival, Brown began woodshedding guitar licks with him during a period in American music when most kids his age were listening to the Beatles.

Callicott taught Brown the tunings and techniques of hill country blues. Tuning his guitar to open G, which he called Spanish tuning, Callicott laid the instrument in his lap and used a pocket knife as a slide.

When Callicott passed away in 1969, Brown picked up open E tuning from Bobby Ray Watson, who also showed him how to play slide licks in the standard position. He says he and Johnny Woods would get together and “ramble the whole weekend from different parties to juke joints” playing music.

In 1971, Brown met R.L., and they became fast friends over their love of hill country blues. For a slide, Brown used a glass Coricidin bottle, a deep-well 11/16 socket or a ¾-inch piece of copper he cut at his construction job.

They played house parties and juke joints throughout the ’70s and ’80s, and when Fat Possum came looking for R.L., Brown went with him, backing him on albums beginning with Too Bad Jim.

While the hills heated up with new fans, better tours and bigger album sales, the next generation of hill country artists were taking notes

While the hills heated up with new fans, better tours and bigger album sales, the next generation of hill country artists were taking notes. Junior’s sons, Kenny, Robert and David, were learning alongside their father, as were Cedric and his uncles Duwayne and Garry Burnside. Lightnin’ Malcolm, Eric Deaton and others from the scene were coming up.

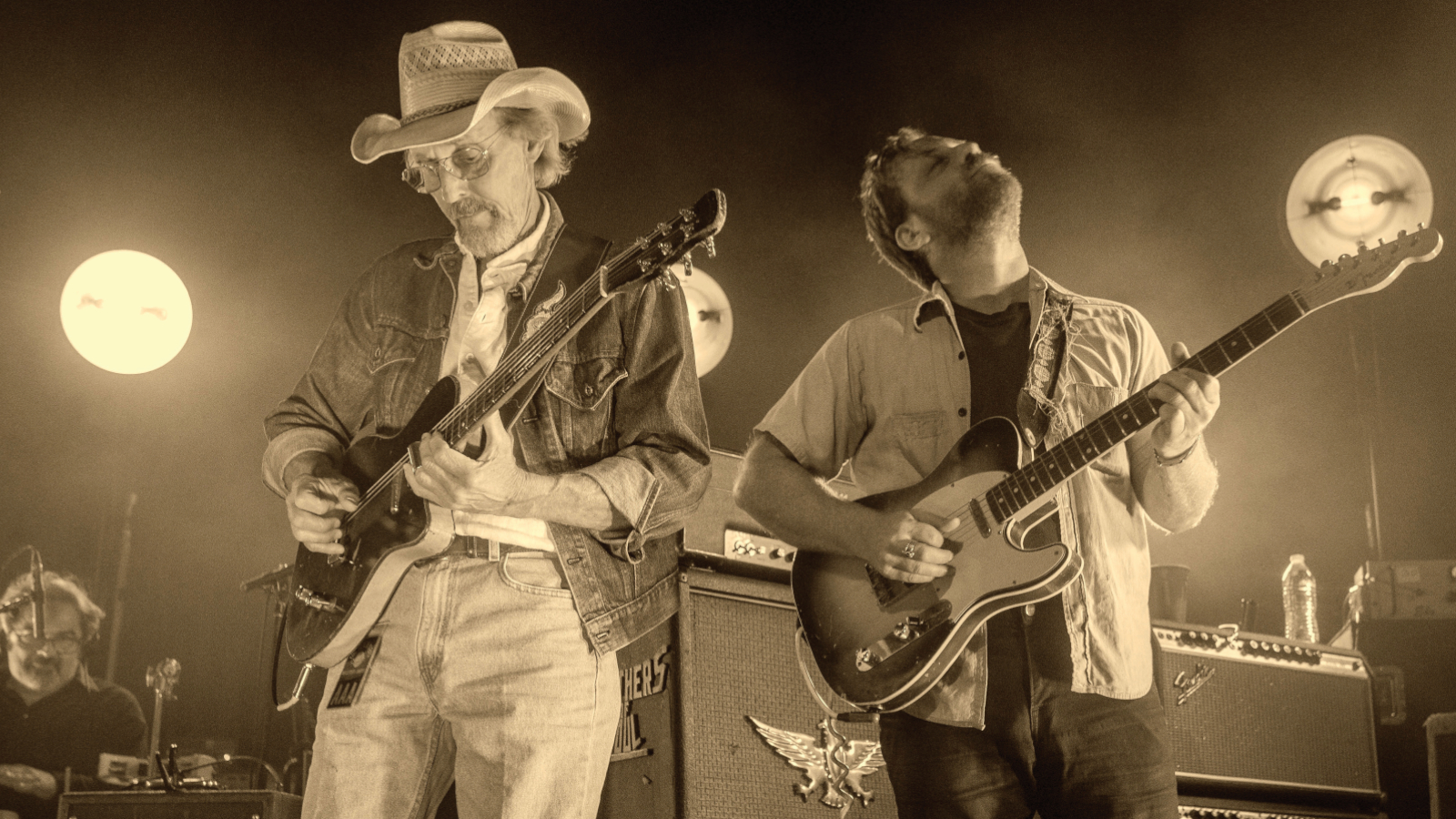

The ones who have arguably made the widest impact, though, are the Dickinson brothers, Luther and Cody, and their friend Cedric. The Dickinsons are the sons of Memphis musician Jim Dickinson, who had played piano on the Rolling Stones’ “Wild Horses” and produced Big Star, the Replacements and Ry Cooder.

Luther recalls that he first heard and saw hill country blues on a 1982 episode of Mr. Rogers Neighborhood that featured Otha Turner and Jesse Mae Hemphill performing fife-and-drum music. Although Luther didn’t get to meet McDowell, his mother carried him to his funeral in utero, and he studied his music from audio and video recordings.

He did meet Turner, though, a decade later at the Memphis Heritage Festival. Turner took him to Junior’s Place for the first time just as Fat Possum was getting off the ground and preparing to record R.L. and Junior.

“Once we befriended the musical families of Otha Turner, the Burnsides and the Kimbroughs, it was on, wide open,” Dickinson says. “They had a juke joint and we had a recording studio. We learned from our peers as well as studying the elders.

“On tour with Burnside in ’97, I would sing along and learn his later style, and then compare that to the earlier, more virtuosic style of his solo guitar work in the ’70s.”

Once we befriended the musical families of Otha Turner, the Burnsides and the Kimbroughs, it was on, wide open

Luther Dickinson

Dickinson’s hill country education was immersive. He became a regular at Junior’s Place, getting to know R.L. and Junior as well as their extended families, and picking up their playing techniques. He began to think about “using folk music forms as frameworks for improvisation,” a concept he put into practice a few years later with the North Mississippi Allstars.

“I had grown up with open tunings, finger picking and slide guitar from my father and his partners, Ry Cooder mainly,” he says. “The hill country guitarists inspired me to play open-tuned, finger-picked slide guitar, electric and loud as hell, but have it respond like an acoustic guitar while using amp response and feedback to create sustain with the slide.”

Luther produced Everybody Hollerin’ Goat, the 1998 album Turner recorded with his Rising Star Fife & Drum Band, and would drive him to performances. By then, Dickinson had formed the Allstars with his brother, Cody, and bassist Chris Chew.

The Allstars put together everything he had learned about hill country blues, from the songbook to the licks and even the fife-and-drum percussion, at times. The band’s 2000 debut, Shake Hands With Shorty, drew together the hill country traditions with Allman Brothers-style improvisation and Chew’s gospel harmonic sense.

I wanted to orchestrate the riffs of Fred McDowell and the solo acoustic work of R.L. Burnside with a rock and roll band

Luther Dickinson

“I wanted to orchestrate the riffs of Fred McDowell and the solo acoustic work of R.L. Burnside with a rock and roll band,” Dickinson says. “At first, we strove to be as traditional as possible. But we eventually opened up and began using the blues songs as vehicles for ensemble improvisation, finding portals for extended jams.”

Dickinson toured with R.L. around the time Cedric took over the drum chair from his father, as the hill country scene started to attract hipster attention in the mid ’90s. All the while, though, Cedric was paying close attention to what his Big Daddy was playing on guitar.

“I would sit there and watch him and look at his coordination, how his fingers moved while he was playing, what time his lyrics would be in, because the music was so unorthodox,” Cedric says. “It was a really crazy rhythm, but he made it sound really great, and so I always wanted to do that. I always wanted to play the guitar and sing, just like my Big Daddy did.”

Dickinson gave him his first guitar, a yellow Harmony acoustic, after the tour, and his uncle Garry showed him open G tuning and some picking and fretting patterns.

“I was playing in open G a lot, and I wrote most of my songs in that tuning and loved it,” Cedric says. “But Garry showed me a little bit in standard, and I was not playing in standard at the time.

“He showed me a pattern in E and then he showed me a pattern in A, and he said this pattern that you did in A, you can go to G and do the same thing. You know, you can go to C and do the same thing, all the way down the fretboard. I was like, ‘Okay, let me just try it in all of them then.’”

Cedric stayed up nights, into the early morning hours some days, practicing chords, change-ups and licks in open G and standard tuning.

It may well be backwards, but if it sounds good, I’ll go with it. That’s where I’m at, even right now today

Cedric Burnside

“When I got on the guitar, I just played with sounds, and I remember some of the top players looking at me, and they’re like, ‘Man, that is so crazy like that. It’s backwards.’ And it may well be backwards, but if it sounds good, I’ll go with it. That’s where I’m at, even right now today.”

By the time Junior’s Place burned to the ground in 2000, two years after Junior passed away, the scene had matured. The Allstars had landed hill country blues on the jam-band circuit and national television, and they brought everyone with them.

Duwayne played in the band for a few years, and for their performance at Bonnaroo in 2004, they brought R.L. and the extended family onstage for a one-off set released later that year as Hill Country Revue.

Unlike other regional blues styles, hill country blues isn’t a dying art, thanks to Brown, the Burnsides, the Kimbroughs and the Dickinsons, as well as Otha Turner’s granddaughter Sharde Thomas, the Black Keys and scores of artists who have taken its influence in new directions.

“I can’t help but be hill country in whatever I write,” Cedric says. “I just let it flow. I don’t try to force anything. If it comes out what somebody might call weird, I just let it come out weird. My heart is just old-school music. That’s all I’ve been around my whole life, and that sound was embedded in me. It’s in my blood, you know, so I just gotta let it do its thing.”

Jim Beaugez has written about music for Rolling Stone, Smithsonian, Guitar World, Guitar Player and many other publications. He created My Life in Five Riffs, a multimedia documentary series for Guitar Player that traces contemporary artists back to their sources of inspiration, and previously spent a decade in the musical instruments industry.