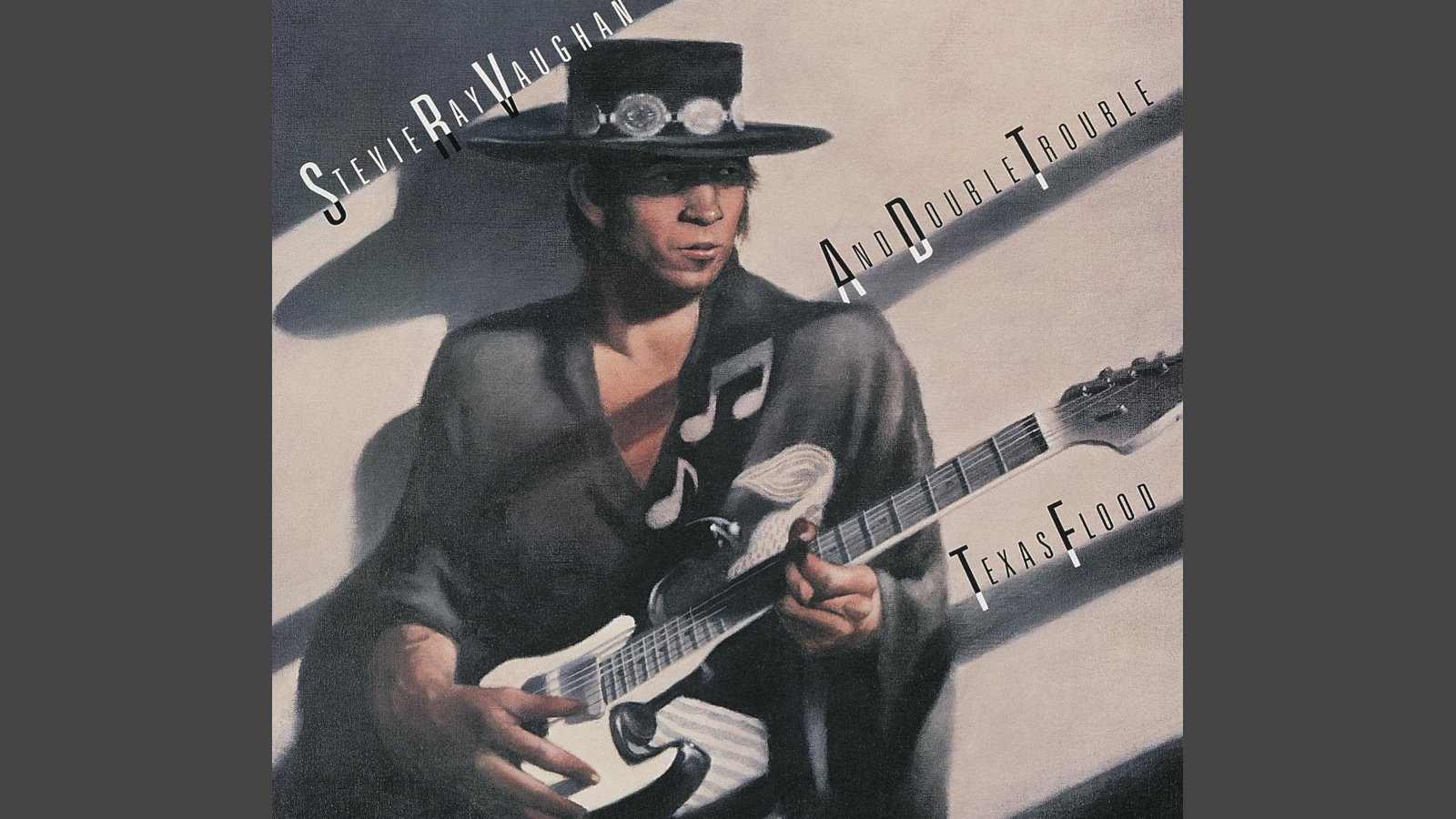

"We Set up in a Circle, Just Like We Did Onstage, Put Mics on Everything and Ran Through the Songs a Couple of Times": Tommy Shannon and Chris Layton Tell the Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s Game-Changing Debut Album, ‘Texas Flood’

Faced with a choice between David Bowie and his own band, Stevie Ray Vaughan took a bet on the blues and unleashed one of the greatest blues-rock albums ever made

After 10 years of grueling one-night stands, forging a reputation as a one-of-a-kind new breed of electric bluesman, Stevie Ray Vaughan was poised to make 1983 his watershed year. Stevie’s Stratocaster sprayed blistering licks across David Bowie’s Let’s Dance, released that same year, punctuating the songs with a dose of Texas grit and primo blues flavorings and taking Bowie’s songs to a whole new level.

It was only half of the story, though, as shortly after the release of Let’s Dance, he delivered his startling, game-changing debut album, Texas Flood.

While Let’s Dance was a fantastic showcase for Stevie to sprinkle some of his Texas hot-sauce stylings, Texas Flood was the full-blown, no-holds-barred, real deal – arguably the greatest blues-rock album made since Jimi Hendrix and Johnny Winter were in their prime. Sure, there were plenty of great discs that might loosely fit the pigeonhole of blues rock, but their emphasis was always on the rock side of the tracks. With Stevie, blues was king.

At a time when there wasn’t too much to excite anyone looking for a hefty dose of full-blooded, ass-kicking, guitar-focused blues, Stevie brought not only outstanding guitar pyrotechnics but a sense of style and flamboyance that made his every performance an event.

Prior to his breakthrough, it had been his big brother, Jimmie, who, with his band, the Fabulous Thunderbirds, had managed to revitalize a tired genre that was mired in predictability and clichéd, extended wig-outs. The T-Birds returned the blues to the juke-joint concept of short, sharp songs that got to the point and moved one’s soul via their feet.

Stevie opted for a different route to express his unique mojo, channeling the wild excesses of Hendrix, mixed with a big chunk of Albert King. While there have always been any number of great guitarists who can fire off Hendrix-inspired fusillades of killer licks, or cop Albert’s trademark moves, no player combined the essential elements of what made those two guitarists so important while retaining a strong sense of their own identity. The fact that Stevie was held in the same high reverence as his iconic influences is testament to the magic that he wielded whenever he broke out his succession of road-worn, battered old Strats.

While 1983 was the year of his big breakthrough, the events of the previous year set the stage for what was to come. The catalyst for everything that came to fruition was Stevie’s appearance at the 1982 Montreux Jazz Festival with his band, Double Trouble, featuring bassist Tommy Shannon and drummer Chris Layton. The trio played their usual blistering set, as can be heard on Live at Montreux 1982 & 1985, but what can also be heard is a section of the crowd who were booing Double Trouble’s ramped-up take on the blues.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

If Stevie and his band were dismayed by the response, they put those thoughts behind them when they met Jackson Browne backstage. The folk-rocker was so impressed by what he had seen and heard that he offered the group free recording time in his California rehearsal studio, Down Town.

David Bowie was also in attendance, and what he saw stuck in his mind as he began recording his next album and needed someone who could really make an impact on his sound. “I figured that Montreux was the key to the whole thing, what with Jackson and Bowie,” Layton tells Guitar Player. “And I really had a strong sense that everything was about to change anyway after that.”

We just set up like a live gig. We didn’t have isolation

Tommy Shannon

Stevie and the band made their way to Browne’s studio in November 1982, working through Thanksgiving to spend three days cutting the tracks that would, unbeknownst to them at the time, become their debut album. “We managed to get two songs down the first day and eight the second day of recording,” Shannon recalls. “We just set up like a live gig. We didn’t have isolation.”

Layton concurs. “We set up in a circle, just like we did onstage, put mics on everything and ran through the songs a couple of times,” he says. “Everything was a first or second take I believe.”

Stevie mostly played his “Number One” guitar on the sessions, an alder-bodied 1962 Fender Stratocaster he mistakenly referred to as a “’59” due to markings on the backs of the pickups. He also brought along Lenny, a brown, maple-neck Strat given to him by his wife, Lenora.

For amps, Stevie used two Fender Vibroverbs and Browne’s own 150-watt Dumbleland Special and 4x12 cab with Electro-Voice EV12L speakers.

While Browne’s gift was much appreciated, the band were unimpressed with the assistance they were provided. Down Town engineer Greg Ladanyi had kindly offered up his services for the ragged band of Texans over the holiday weekend, but he wasn’t interested in doing much more than capturing the group on tape. Stevie was unhappy with the sound he was hearing.

As it happened, Richard Mullen, a musician and friend who had run sound for them in Austin, was in Los Angeles. Over the group’s dinner break, Mullen encouraged Stevie to speak up and demand the sound he wanted. Returning to the studio, they found Ladanyi was gone and another engineer in his place. Newly emboldened, Stevie told the man that Mullen would be taking over the session. Within an hour, things were sounding much better.

As Mullen recalled to Guitar World in 2004, he used two Shure SM57s on Stevie’s amps: one on a Fender Vibroverb and one on the 4x12. “Stevie played through two Vibroverbs, but I only miked one of the speakers in one of them,” Mullen said. “I positioned the mics about three or four inches off the cabinet at about a 45 degree angle to the cone. The only effect he used was an Ibanez Tube Screamer.”

I remember thinking that it was pretty strange to be getting a call from David Bowie

Chris Layton

The band only cut the backing tracks at this point – the vocals would be tracked at Riverside Sound in Austin – but as Layton recalls, the plan all along had been to record the equivalent of a demo. “We weren’t making the tapes to make an album,” he says. “It was just to record our songs. It just turned into an album later.”

Double Trouble played a few dates in L.A. to help pay for their room at the Oakland Garden Hotel while they were cutting the record. Layton recalls being woken at 3:30 in the morning by a phone call. “I remember thinking that it was pretty strange to be getting a call from David Bowie,” he says with a laugh. The British musician had not forgotten Stevie’s performance at Montreux months earlier. Now in the middle of making Let’s Dance, he decided Stevie’s guitar work was the missing ingredient and tracked him down.

“He wanted to speak to Stevie, so I had to go wake him up and tell him David Bowie’s on the phone,” Layton says. “They seemed to be talking for quite a while. When he came off the phone he told me that Bowie wanted him to play on his new album.”

As it happened, he had never really been a fan of Bowie’s music. “Stevie never listened to David Bowie,” Shannon says. “The songs on Texas Flood showed you what Stevie loved, you know?” Adds Layton, “He respected Bowie, but he definitely wasn’t a fan per se. He thought he was talented, and he’d obviously had a great career.”

Regardless, no one could deny it was a great opportunity for Stevie. “Management told Stevie he really had to do Bowie,” Shannon says. “They didn’t anticipate that there would be a conflict with Texas Flood, because at the time we hadn’t even secured a deal or anything. We didn’t even know that we were making an album!”

Of course, with the recordings for Texas Flood completed, there remained the task of deciding what to do with them. “We called our manager, Chesley Millikin, and suggested that he call John Hammond to see if there was something we could do,” Layton says. An active musician, talent scout and producer since the 1930s, Hammond was behind the careers of countless musicians, including Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Michael Bloomfield and George Benson. “Apparently, when Chesley told John that we had a whole record’s worth of music ready, he said he’d get us a record deal with Epic. The deal was on the table before Stevie even started recording with Bowie.”

Management told Stevie he really had to do Bowie. They didn’t anticipate that there would be a conflict with 'Texas Flood'

Tommy Shannon

With things looking good on the band front, in January 1983 Stevie traveled to the Power Station studio in New York to begin working on Let’s Dance. Hearing him for the first time, producer Nile Rodgers didn’t share Bowie’s enthusiasm for the guitarist, whose solos he felt leaned too heavily on Albert King.

He soon changed his mind after Stevie loosened up and began to draw from his own unique palette of rich blues flavorings. Rodgers later admitted that he’d misunderstood Stevie’s intention: Where a lesser player would have unloaded licks all over the track, Stevie laid back, embellishing with just what the song required. He may have been a masterful exponent of the extended blues solo, but Stevie knew when to play and when to let the song breathe. He cut all his solos in a couple of days over the completed backing tracks, listening to each song once before adding his contributions in no more than two or three takes – although the first take was usually the one selected.

Stevie’s playing and tone on Let’s Dance was impeccable. Using a Strat and a Fender Super Reverb, he brought a richness of sensitivity and atmospheric depth to the songs that was transformative. Although Rodgers changed his opinion of his playing, Stevie himself joked that he basically played his favorite Albert King licks, and told one interviewer that Albert had ribbed him for doing so. But there is no doubt that Stevie’s mojo was all his own.

When Bowie’s album was released in April 1983, the reviews were uniformly strong. Stevie’s playing was often cited as a particular highlight, with good reason. It’s hard to imagine that the album would have hit home with such resonance without his dynamically sensitive Strat stylings.

Although Texas Flood was set for release, Stevie was scheduled to play on Bowie’s extended world tour to support Let’s Dance. Reportedly, Bowie’s camp intimated that Double Trouble could open for Bowie on selected dates, but Shannon and Layton have slightly different memories and perspectives on this.

“David definitely told us that we could open for him from the outset,” Shannon says. Layton, however says, “Bowie was actually a little vague about the prospect of us opening.” Although he acknowledges that the singer and Double Trouble agreed it would be great to tour together when they met at Montreux, “my instincts were that he wanted Stevie to play on the record, and having Stevie on that record was his prime concern, not what Double Trouble would do.”

As rehearsals for the Let’s Dance tour got underway in Dallas that April, it was evident Stevie was bringing an entirely new dimension – a cool blues-nuanced vibe – to Bowie’s older songs, something revealed in recordings that have surfaced over the years.

[SRV] was really unfamiliar with Bowie’s material, and it wasn’t in his heart musically

Tommy Shannon

But as Shannon recalls, Stevie was out of his element. “He didn’t seem that happy about the music that he was playing with Bowie in the rehearsals,” the bassist explains. “He was really unfamiliar with Bowie’s material, and it wasn’t in his heart musically. Stevie always lived by what was in his heart, first and foremost. I don’t think he listened to anything before the rehearsals started. He just picked it up as they went along, same way as when he did the recording session with Bowie.”

As the rehearsals drew to a close, the question of whether Double Trouble would come along was finally decided by Bowie’s camp. Not only would they not open for Bowie but Stevie was not even allowed to discuss the band’s upcoming debut album in interviews.

For Stevie, this was completely unthinkable. “That really pissed Stevie off, because he didn’t want to leave our band behind,” Shannon says. “There was never any indication why Bowie changed his mind that we knew of. I wonder if it was possible that he was using the notion of us opening as some kind of persuader to make sure Stevie would do the tour. I’m sure he never expected Stevie to pull out at the last minute – to give up all the big touring lifestyle, the top hotels and whatever to go back on the road in our milk truck.”

Whatever the case, that’s exactly what Stevie did. “I really respected Stevie for that,” Shannon says. “He was just so into what we were doing that he just couldn’t leave it.”

According to Layton, the crux of the problem was that Stevie was not able to discuss the matter with Bowie. “I think Stevie had a good relationship with Bowie when they first spoke and when they did the album together,” he says. “But I think it suddenly started to turn into something else on Bowie’s part when the tour came into the picture.

“When Stevie wasn’t able to get a hold of Bowie to address the issue directly, I think he knew that he had to be true to himself. That was one thing about Stevie: He was one hundred percent natural. He couldn’t fake things. Stevie just said, ‘You know what? I’m going to stay with my band.’

“Who knows what would have happened if he’d done the tour,” he continues. “These were the conversations Stevie had with us: how he could do the tour and take care of us; how we could even get paid as a band. I said I couldn’t really see how that was even practical. How could it ever work out, especially if the tour went on for a couple of years, or even longer?

“But at the same time, I didn’t want Stevie to think he had to make us his main concern. Stevie always said that the thing that he wanted in life, when it came to his music, was for us to all have our own band and to play what he loved, and I wondered how that could ever have figured in the idea of going on tour with Bowie. It troubled him that he could even do the tour on that basis, and it troubled me and Tommy, as we wondered how we could even have a band if we were on hold for two or three years.”

Stevie just said, ‘You know what? I’m going to stay with my band'

Chris Layton

Carlos Alomar, Bowie’s guitarist and band leader at the time, has recounted in interviews that he and Stevie discussed the tour’s potential to help promote Double Trouble and Texas Flood. He remembers cautioning Stevie that it was Bowie’s show, and as a band they were all there to play their role in that show; the chance that the tour could make a significant impact on Stevie’s fortunes as a solo artist were probably slim.

Unwittingly, perhaps, Alomar helped firm up Stevie’s resolve to abandon the tour, regardless of its immediate benefits for his career. Although Alomar was unhappy that Stevie left so close to the time they went out on the road, his departure opened the door for Alomar’s long-standing musical partner Earl Slick, a frequent contributor to Bowie’s albums and live show, to come onboard as Stevie’s replacement.

Before Stevie pulled out of the Bowie tour, Epic had been unsure how to make the most of his appearance on it. The label had even debated whether to hold back Texas Flood. Despite this, a couple of New York City showcase events to promote the record were held in early May 1983, and it was clear to those present – including many big names in the industry – that Stevie’s charisma and raw, unbridled access to the deep core of his soul had the ability to transform the face of blues guitar.

He was the ultimate crossover artist, a bluesman who could hold his own with any legend on the rock or blues side of the musical spectrum. Moreover, he commanded the respect from his peers that can only be earned.

With the Bowie matter now moot, it was all systems go. Stevie and Double Trouble threw themselves into the full-on promotion of their blistering new album. Released on June 13, Texas Flood received some surprisingly mixed reviews. Certainly, the climate was much friendlier to the kind of synth-driven, dance-oriented music featured on Bowie’s Let’s Dance than it was to Stevie’s more traditional blues-rock. Yet, against all expectations, Texas Flood started to pick up serious airplay.

Once the record’s two singles, “Love Struck Baby” and “Pride and Joy,” received heavy rotation on MTV, the die was cast. With his lean build and signature bolero hat, Stevie even had the visuals to compete with the style-obsessed bands that were dominating MTV’s scheduling. Together, they helped Texas Flood rack up sales figures that even the most optimistic execs at Epic couldn’t have hoped for.

The record’s huge success came as a surprise to the band. “Well, I know we were all real pleased with it when it was finished,” Layton says. “But of course, when you make a record, you live with it for a long time before the public ever hears it, so it’s not like, ‘Wow, that sounds amazing,’ if you hear it on the radio or something. But it was real satisfying to see that people picked up on that special thing that we had as a band, and Stevie’s genius. It happened so quickly for us though. When it was released and started selling right away, it was like, ‘Boom! Shit’s really happening for us now!’”

Stevie was real excited when the record came out, but like me and Chris, he had no idea it would become the big success that it did

Tommy Shannon

Forty years on, Layton still looks with pride upon the group’s achievement with Texas Flood. “The record is what it is,” he says. “I think everyone, to some degree, looks back at things they’ve done with a slightly critical ear, but I think it’s a real good picture of who we were at that time. It’s always too late to do what you could’ve done, and things are always what they are. From our way of living, it was an all-or-nothing kind of thing; our life was about the music and the band. It wasn’t like we had a big strategy, you know? We were a band, we played shows, made a recording and hoped to put a record out and see how things went. Everything that took off was almost a wonderful interruption of the basic way that we saw things going.”

Shannon echoes those sentiments. “We were real happy with it. We all thought it sounded like a great picture of what we sounded like live – it wasn’t a big production. Stevie was real happy with how it turned out. We didn’t really have any expectations that it would be successful – we were just doing our record, y’know? We loved what we were doing, and Stevie loved playing with us so much that we were all real happy with how it turned out. Stevie was real excited when the record came out, but like me and Chris, he had no idea it would become the big success that it did.”

Stevie and Double Trouble’s career trajectory was vertical, with a rocket. He became the hippest name to drop among a rapidly expanding cadre of established legends, with the likes of Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Buddy Guy singing his praises. With the opportunities came the temptations that high-profile success brings, and Stevie developed some serious addiction problems that threatened to derail his career for a couple of years before he finally managed to put his dependency problems behind him.

Whenever an artist is taken before their time, the temptation to wonder what they might have gone on to achieve is irresistible. The fact that the last two albums Stevie worked on, Double Trouble’s In Step and Family Style – recorded with his brother, Jimmie – featured some of his finest playing certainly boded well for his future.

Once upon a time you needed the detective skills of Sherlock Holmes and some seriously deep pockets to track down live recordings and scratchy videos of Stevie and his band plying their wares around the world in 1983. Now all you need is YouTube and the ability to type “Stevie Ray Vaughan 1983” into the search to be rewarded with hours of astounding footage that will enthrall and amaze you.

Unsurprisingly, the surviving members of Double Trouble never expected to be discussing their music 40 years hence when they laid the tracks down. “I don’t even know what to think about that,” Layton says. “I definitely couldn’t have imagined we’d be here this far down the line discussing it.”

I definitely couldn’t have imagined we’d be here this far down the line discussing it

Chris Layton

There are always the inevitable ’what if?’ thoughts when an artist is taken way too soon. “I’ve probably thought about everything a hundred different ways, a hundred different times,” Layton says. “But I stopped going down that path, because it didn’t really serve any real purpose, you know?”

Shannon believes that, had Stevie lived, their music would have continued to evolve. “I think Stevie wanted to get some horns in the band and we were gonna change the style a little with a horn section in there,” he says.

No doubt, Stevie would have been bemused to learn in 1983 that his music would be pored over and revered by blues fans and scholars alike for decades to come. It likely would have startled him to think future guitar greats would cite him as a primary influence, or to hear that he would be placed on equal standing in music history with the players he himself idolized.

Remarkably, it all began with an album recorded on gifted studio time. But the fact that it had any impact at all is down to the phenomenal talent that was Stevie Ray Vaughan.

Order Texas Flood here.

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.