“They had strippers and crabs everywhere... People would get pissed and start shooting at the stage.” Stevie Ray Vaughan talks his Number One Strat, Dumble amps, and craziest gigs in a classic GP interview

The following story originally appeared in the October 1984 issue of Guitar Player.

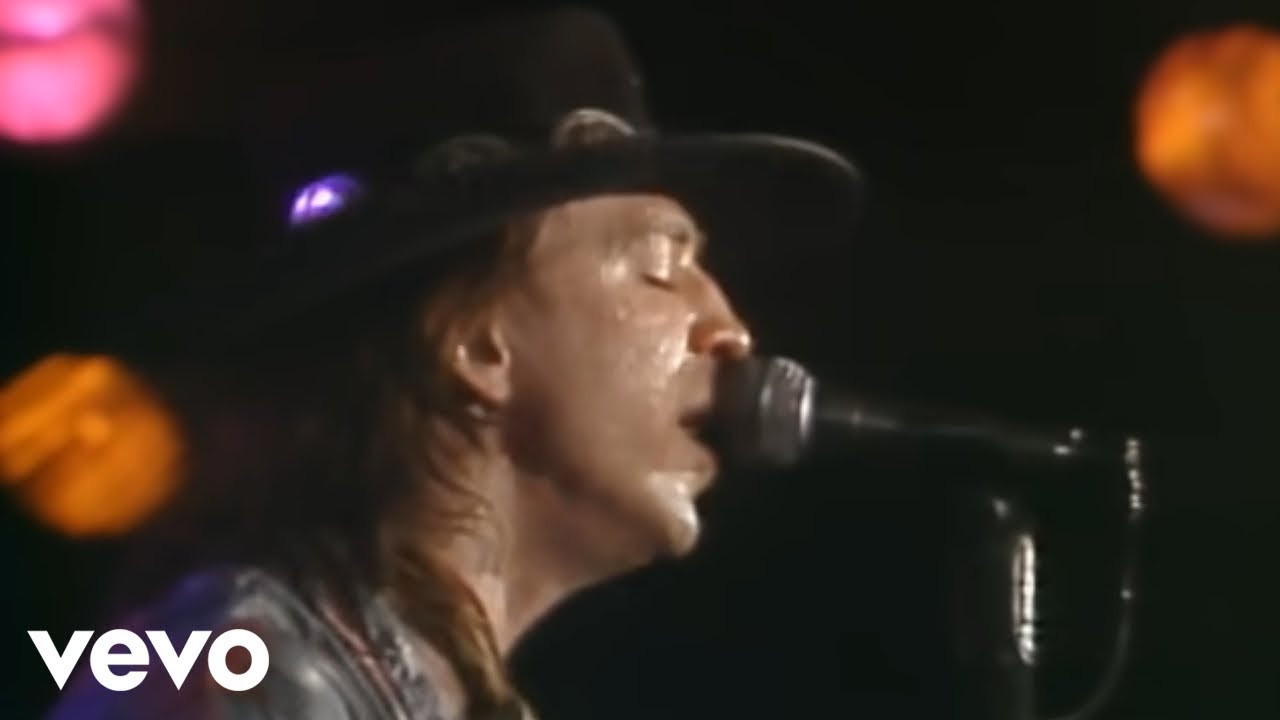

Several hours before show time, Stevie Ray Vaughan sits alone on a weary couch in a backstage dressing room, his head buried in his trusty, albeit beat-up, Stratocaster. Dressed in Japanese happi coat, wide-brim black gaucho hat, black slacks, and pointed-toe shoes, Vaughan limbers up, and greets the occasional visitor with a vice-like handshake and a bit of tentative conversation. It's a ritual the slight but wiry Texan has been through countless times, but he still appears a bit nervous.

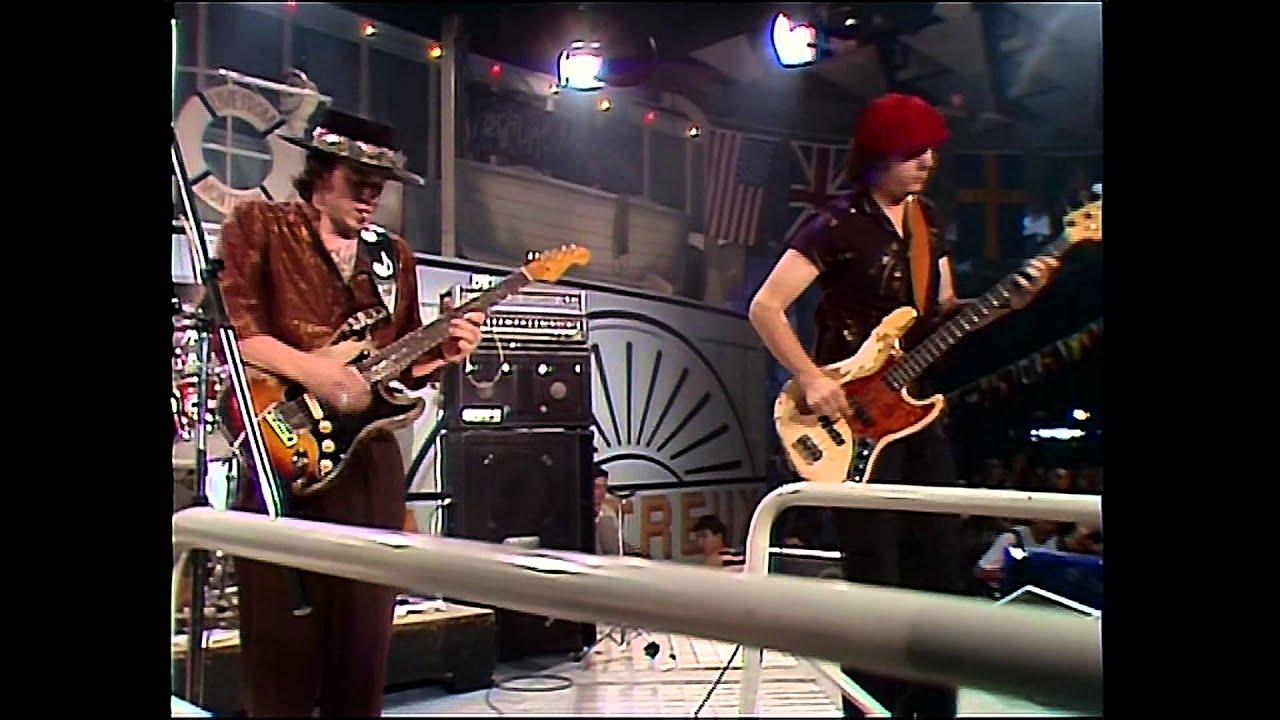

Once plugged in onstage, however a completely different Stevie Ray Vaughan emerges – cool, confident, flamboyant, and even a bit cocky. Before the crowd is finished applauding the opening instrumental, Testify (from his debut album, Texas Flood), he and the two-man rhythm section known as Double Trouble (bassist Tommy Shannon and drummer Chris Layton) launch into Jimi Hendrix's Voodoo Chile (from the group's impressive follow-up, Couldn't Stand the Weather).

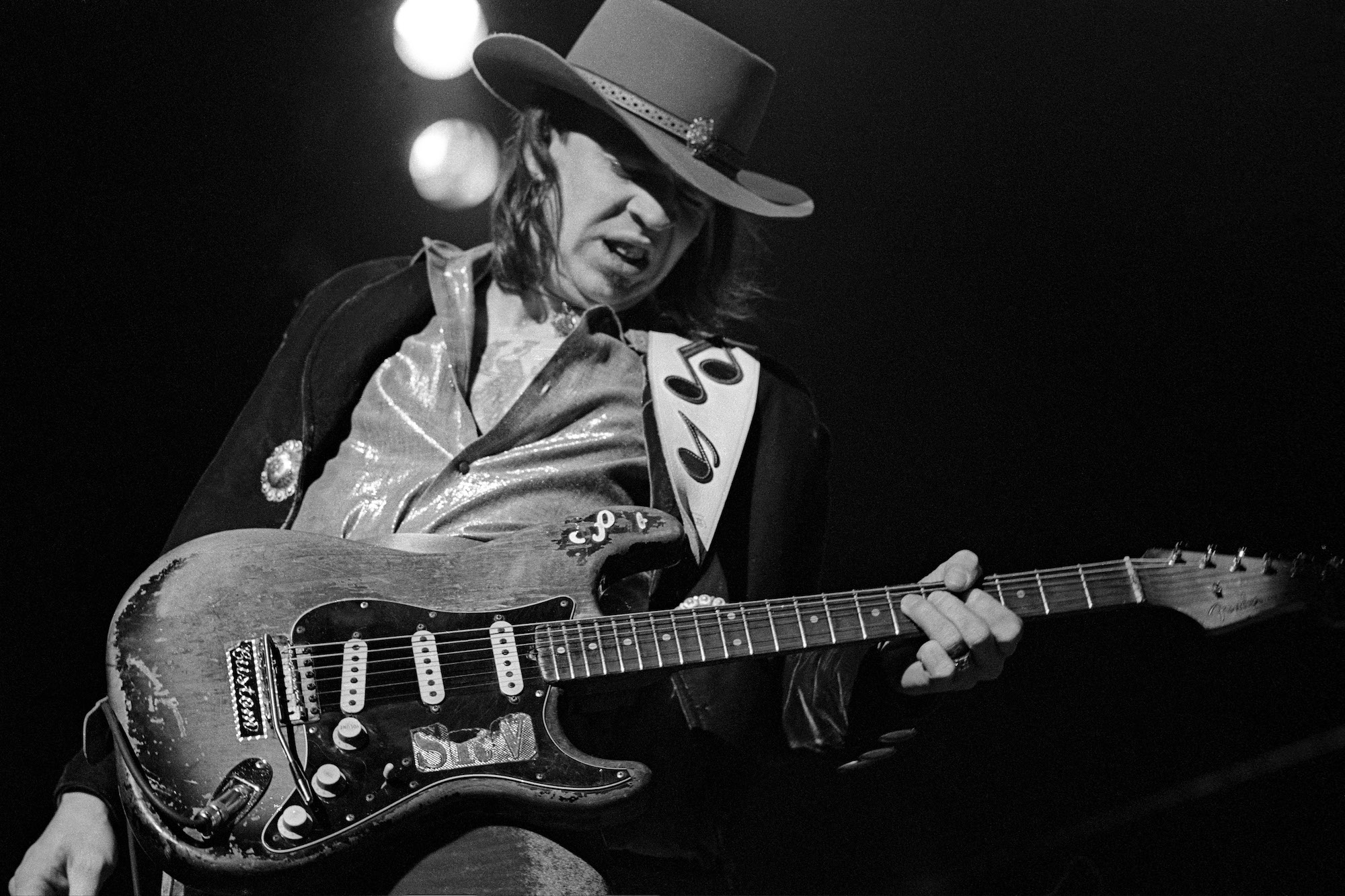

For the next 90 minutes, each vocal phrase, every guitar solo and fill, is delivered at full-throttle. Even during almost inaudible parts of his solo in the dirge-like Tin Pan Alley, Vaughan's intensity never subsides. He doesn't just play his guitar; he mauls it – as evidenced by the nonexistent finish and 1/4"-deep scratches on the face of his battered '59 Fender Strat.

By the end of the set, closing with Hendrix's sonic tour de force Third Stone From The Sun, Vaughan has played the guitar behind his head, off his shoulder like a violin, behind his back, and on the floor – standing over the cutaways with one hand firmly on the guitar's neck, the other pulling up on the vibrato bar.

While making vintage guitar collectors wince and teachers moan, Stevie Ray has given the biggest exposure in years to one of the most fundamental but unsung musical forms: the blues. And with every achievement and accolade he has received since he burst onto the charts on David Bowie's critically acclaimed album Let's Dance (lauded in large measure because of Stevie's searing guitar work), the 30-year-old has shared his honors with the bluesmen who preceded him and with the genre itself.

“Most of all, I'm glad to see the blues getting the recognition it deserves,” the guitarist has emphasized on more than one occasion.

After being lifted out of the Austin, Texas, blues scene to play on Let's Dance, Stevie Ray went back to his hometown group, Double Trouble, and teamed with A&R legend John Hammond to produce Texas Flood, which took top honors in Guitar Player's 1983 Readers Poll as Best Guitar Album.

In the same balloting, Vaughan racked up two more blue ribbons – completely dominating the New Talent category and edging out no less than Eric Clapton as Best Electric Blues player – to become the first triple-crown winner since Jeff Beck's 1976 hat trick.

With Texas Flood still selling strongly, Double Trouble released Couldn't Stand The Weather, which hit the Billboard pop chart on June 13 of this year at (144, leaped up to 63 in its second week, and bulleted to 37 and 31 in the following two weeks.) “What's happened, I guess,” drawls Vaughan, “is that we've come from playing clubs to where we can pretty much fill a 5,000-seat hall now. We just worked our butts off.”

Vaughan's popularity is as worthy of scrutiny as his phenomenal guitar playing. While numerous blues-based rockers have become guitar heroes after crossing over to the rock camp – including Clapton, Michael Bloomfield, and Jimi Hendrix – Stevie is the first since fellow Texan Johnny Winter (who also eventually drifted into out-and out rock and roll) to make the major leagues by sticking with the blues.

His videos of Love Struck Baby (from Flood), Couldn't Stand the Weather, and Cold Shot (from Weather) are in steady rotation on MTV's playlist, and Pride and Joy (from his debut LP) received substantial airplay on FM stations. He teamed with George Thorogood for a tribute to Chuck Berry at this year's Grammy awards, and has appeared on such unlikely TV shows as Solid Gold.

Most people's first exposure to Stevie Ray's searing solos, of course, was via Bowie's Let's Dance. But even though the material was not the type of R&B he had mined in Texas bars for more than a decade, Vaughan's razor-edged leads were pure blues, relying heavily on Albert King for tones and riffs.

Texas Flood revealed a debt to blues masters such as Jimmy Reed, Magic Sam, Lonnie Mack, Buddy Guy, and Hubert Sumlin, and paid that debt with interest. Opening for coliseum acts such as Men At Work, the Moody Blues, Huey Lewis and the News, and the Police – Stevie riveted audiences with his passionate homages to Jimi Hendrix, including Voodoo Chile, Little Wing, and Third Stone From The Sun.

While countless guitarists have been influenced by the creative genius of Hendrix, few have attempted to cover any of his songs.

There are several obvious similarities between Vaughan and the late southpaw – each led a trio, had incredible control of feedback and volume with a minimum of effects devices, and could sing adequately but not well enough to make it strictly as a vocalist. But what sets Stevie above other pretenders to the Hendrix throne is his ability to play lead and rhythm simultaneously – like Jimi, he fires a nonstop barrage of chords, licks, hammer-ons, pull-offs, and unorthodox tricks at the listener. Vaughan's guitar technique doesn't just impress; it overwhelms.

Instrumentals such as Rude Mood (from Texas Flood) and Scuttle Buttin' (Weather) are textbook studies of the pedal-to-the metal Vaughan style, while Lenny (Flood) is reminiscent of Hendrix' most sensitive ballads, and Stang's Swang (Weather) reveals a firm grounding in organ-trio guitarists such as Kenny Burrell, Grant Green, and early George Benson.

Unlike many other guitar-based trios, Double Trouble overdub next to nothing in the studio; the 12-inch pieces of vinyl are accurate representations of the sort of thing Vaughan & Co. have been playing onstage since they formed in 1978 – following Stevie Ray's stints with the Cobras and Triple Threat Revue.

Couldn't Stand The Weather made use of a few of Vaughan's Texas buddies – saxophonist Stan Harrison, Fabulous Thunderbirds drummer Fran Christina, and brother Jimmie Vaughan (guitarist/leader of the T-Birds) – and at press time, Stevie was finalizing plans to augment the trio further for his October debut at New York's Carnegie Hall. To be recorded for a possible live LP and video, the concert will tentatively include Jimmie Vaughan, organ legend Booker T. Jones, and the Tower Of Power horn section as special guests.

A lot has happened to Stevie Ray Vaughan since he was featured in the August '83 Guitar Player. In the following interview, he talks about his techniques and tricks, his major influences, his collection of Stratocasters, and the most important element to Double Trouble's sound: soul.

There seems to be a long tradition of Texas guitar players.

“Yeah. I don't know if any of us know what it is. It's just in the air, you know.”

Does the environment of friendly competition improve the caliber of the players?

“Sure, yeah. For some reason, nobody lets go of the soul of it. Same way with a lot of San Francisco players. There are a lot of musicians in the Bay Area who do remember how to play from their heart – as opposed to a lot of the things in LA that are missing that; it's just show time. But in Texas especially, there seems to be a lot of musicians interested in pulling for each other and working together, and it really, really helps a lot. It makes you a tighter unit, and it keeps you right in your heart. And that has a lot to do with your playing.”

Austin musicians definitely have strong feelings of community – even though a band like Asleep At The Wheel plays Western swing, the Fabulous Thunderbirds play blues, and Eric Johnson plays fusion.

“It doesn't matter. People still work together.”

Can you spot a Texas guitar player by hearing him?

“Oh yeah. I don't know what it is – I just can hear it. Maybe it's the water [laughs].”

What's the blues scene like in Austin?

“There's some crazy jam sessions going on down there. Hubert Sumlin is staying down there now, and Mel Brown is living there, and Lonnie Mack. He's a great cat. Also Buddy Guy comes down and hangs out for two or three weeks a month, just about.

“It ends up where all those guys are up there playing. And Mel Brown plays [Hammond] B-3 organ like nobody's business, too. Antone's closes down at 2:00, but it's nothing out of the ordinary for it to be 4:30 when the last set's over – after starting at midnight. A four-hour set ain't too bad.”

I heard stories years ago about a jam session at Antone's with B.B. King, yourself, and Luther Tucker.

“Yeah, that was the night B.B. scared me to death. He sat on his amp and played rhythm for me for about four songs. And then he stood up and played one note – [picks up an acoustic guitar and plays a high, stinging vibrato]. You know, one of those B.B. notes that make you go, 'Haaugh!'”

What you just played sounded exactly like B.B. Did you work on that a lot?

“Just listened.”

When you first took up guitar, was it blues that you were mainly attracted to?

“A lot – because of my brother Jimmie. He'd bring home records by B.B. and Buddy Guy. And he was the one who hit me with Lonnie Mack, too; the first record I ever bought was The Wham Of That Memphis Man. Jimmie brought home a Hendrix record, and I went, 'Whoa! What is this?' I'll never forget that.”

Did Jimmie show you things on guitar, or did you just pick up things from hearing him around the house?

“At first, he taught me a couple of things, and then he taught me how to teach myself – and that's the right way.”

Your brother was heavily influenced by another Texas bluesman, Freddie King. Did that style rub off on you as well?

“Yeah, it did. I had that instrumental album of his [Let's Hide Away And Dance Away]. Jimmie used to know him pretty well, but Freddie wouldn't talk to me in public. In private, but not in public. I guess I was a young white boy he didn't want to be seen with [laughs]. I played with him once, sitting around a table when no one was around.”

What specifics did you get from various players?

“I got a lot of the fast things I do from Lonnie Mack – just the ideas and the phrasing. Like on Scuttle Buttin'. [plays a barrage of chicken-picked pull-offs]. That's really a Lonnie Mack thing – that's dedicated to him. I got a lot of turnarounds from Freddie King.”

Who were the main blues players you heard on records?

“Well, let's run 'em down. There was Buddy Guy, Muddy, of course, and all the various guitar players who were with him [including Jimmy Rogers and Pat Hare], Hubert Sumlin, Lonnie Mack, B.B., Albert King, Freddie, Albert Collins, Guitar Slim – he'd just turn it all the way up. I can just imagine people saying, 'Slim, why do you always play so loud?' 'Because it sounds like this' [laughs].”

We got 90 bucks a night per person, and we were never awake during the day, so there wasn't any way to spend it

Johnny Winter was the first white Texan bluesman to make it on a big scale. Were you influenced much by him?

“Yes, although I hadn't heard him as much then. I listened more to people like Albert Collins, Albert and Freddie King, [and] Johnny Guitar Watson. But around '71 or '72, I got to jam a lot with Johnny over at Tommy Shannon's house – that was a little bit after his initial big success.”

How did you meet Tommy Shannon and Chris Layton?

“I've known Tommy for years and years – since about '69. I was in Dallas playing at this after-hours place called the Fog, and he'd just left Johnny Winter. He claims that he walked in and saw this little person playing guitar [laughs]. I was 15 or something – wasn't supposed to be in that club.

“We've played together in bands off and on ever since. Chris and I have been together about six years, I guess. I met him through Joe Sublett of the Cobras – they were roommates. I went over to the house once and Chris was in the kitchen with his headphones on, blasting away on the drums. When he was finished, I told him I needed a drummer, so he quit his other band.”

Was he basically a blues drummer when you found him?

“No, but he could do it. Took him about 15 minutes to learn how to do a rub shuffle right. A lot of it was just natural.”

Did you play in clubs in Dallas before you moved to Austin?

“Yeah. I could make decent money there, playing the Cellar, but it wasn't the kind of place you'd want to hang too long. That was the only place that let me do what I wanted to do – because nobody cared about shit there. They just had strippers and crabs everywhere [laughs]. If you really wanted to come in there and play, they'd let you. A couple of times, people would get pissed and start shooting at the stage. You had to duck and keep playing [laughs].

“I played there from age 14 until I was 18. There was a Cellar in Dallas and one in Fort Worth. We'd play two sets in one town, drive to the other club, and play two more sets. We got 90 bucks a night per person, and we were never awake during the day, so there wasn't any way to spend it.

“I was trying to stay as close to this kind of music as I could, but at the same time I was going through a phase of playing through Marshalls – just turning up to 10 and being a teenager. I remember doing some Allman Brothers songs, which I liked at the time – skirting the outskirts – but we were also doing Buddy Guy and B.B. King stuff.”

Have you had a hard time playing blues as an opening act to major rock bands?

“No, the audiences reacted real well to it. I think more of the people on the Moody Blues tour were aware of what we were doing. When we played with Men At Work, it was still a lot of fun, but there were mainly 13-, 14-, and 15-year-olds, and a few of them knew how to slingshot dimes, you know [laughs]. But a lot of those kids really went for it, even though they weren't expecting it.”

Your playing on Let's Dance isn't along the lines of Texas Flood; it's more like Albert King.

“I kind of wanted to see how many places Albert King's stuff would fit. It always does. I love that man. When that album first came out, Albert heard it. He said, '[sneering] Yeah, I heard you doin' all my shit on there. I'm gonna go up there and do some of yours" [laughs].

“We were doing this TV show right outside of Toronto – Hamilton, I think – and during the lunch break, Albert went around to everybody in there looking for an emery board. I didn't think anything of it. We were jamming on the last song, Outskirts Of Town, and it comes to the solo, and he goes, 'Get it, Stevie!' I started off, and I look over and he's pulling out this damn emery board, filing his nails, sort of giving me this sidelong glance [laughs].

“I loved it! Lookin' at me like, 'Uh-huh, I got you swinging by your toes.' He's a heavy cat.”

Do you ever play with your thumb to get an Albert King sound?

“I play with a pick and a finger. I used the round end of the pick, too. You break less of them and don't get tangled up in the strings. Sometimes I play with both together, or I'll palm the pick and use my fingers, or sometimes I'll just 'Hubert' it [play with bare fingers a la Hubert Sumlin].”

Is that to get a variety of tones?

“Different tones, different moods. It depends on how the amps are working that night, how dead the strings are, how much I can hear, how crazy I'm feeling.”

On Cold Shot, did you play through a Leslie speaker to get that underwater sound?

“It's a Fender Vibratone, which is basically like a Leslie. It's a 10" speaker with a Styrofoam rotor in front of it – so the speaker is stationary, but a drum with a slit in it revolves – and then you mike it from both sides.”

On Couldn't Stand The Weather, were there any tracks where you cut a rhythm part and overdubbed a lead, or vice versa?

“No, on some of the songs I just played and then did the vocal later – which sometimes is a mistake, because you play differently when you're not singing than you would if you were singing along. A lot of times the licks won't match the phrasing of the vocals. Most of the solos were cut live. I redid one line in Voodoo, because my amp went crazy on me. The punch-in didn't come off very well; it still doesn't sound right to me.”

Texas Flood sounds like there are hardly any overdubs.

“There aren't. Only if I broke a string or something.”

So you played the lead and rhythm in the same take, rather than laying down a rhythm track and soloing over it later?

“Right. We redid a few vocals, but some of them were live, too. That was mainly to go back if a word was left out or not real clear, plus, we got a better vocal sound by redoing them. I don't think that's cheating too much.”

Right now, I use a Howard Dumble 150-watt. He calls it the Steel String Singer; I call it the King Tone Consoul – that's s-o-u-l

Do you set up in the studio the same as onstage, or do you use drum booths and headphones, etc.?

“The first record, we pretty much set up like we do onstage, but we did have a few baffles between us. We went ahead and used headphones like on one ear. We couldn't see the control room; it was at the other end of this place with a bunch of stuff in between and no window. I like it a lot that way.

“That was at Jackson Browne's rehearsal studio called Downtown, in LA. For Couldn't Stand The Weather, we were in the Power Station [in New York], and all the walls separating the rooms are glass, so we were separated but we could still see each other. So I could go in and play louder than shit.”

Do you usually record pretty loud?

“Sometimes. Sometimes real quiet, like on Tin Pan Alley.”

What about Voodoo Chile?

“Had it up as loud as I could – and I was in the same room with it.”

Do you use the same amps in the studio as onstage?

“Yes. Two Fender Vibroverbs – they came out in '63; they're number 5 and 6 off the production line, but I bought them in two different places at two different times.

“It's basically like a Super Reverb with a 15 and a shorter cabinet, and it has no midrange knob – it's preset on 4, I think. My favorite setup used to be two Vibroverbs and two Supers – just stack 'em up. Just let the Vibroverbs handle the bottom. I had one Super set clean, and the other where I could just turn it up or down wherever I wanted it.”

You don't use the Super Reverbs now?

“Right now, I use a Howard Dumble 150-watt. He calls it the Steel String Singer, I call it the King Tone Consoul [laughs] – that's s-o-u-l. It's like an overgrown Fender tube amp. Some Dumbles – like the Overdrive Special – you've got to know what you're doing with them, because they'll get away from you and take you with 'em.”

Was John Hammond in the studio for the first album?

“No, he wasn't there at all, except for the mixdown and the mastering. This time he was there a lot for the recording.”

You just keep listening and trying to find the sound, because it's in your hands as much as anything. It's the way you play

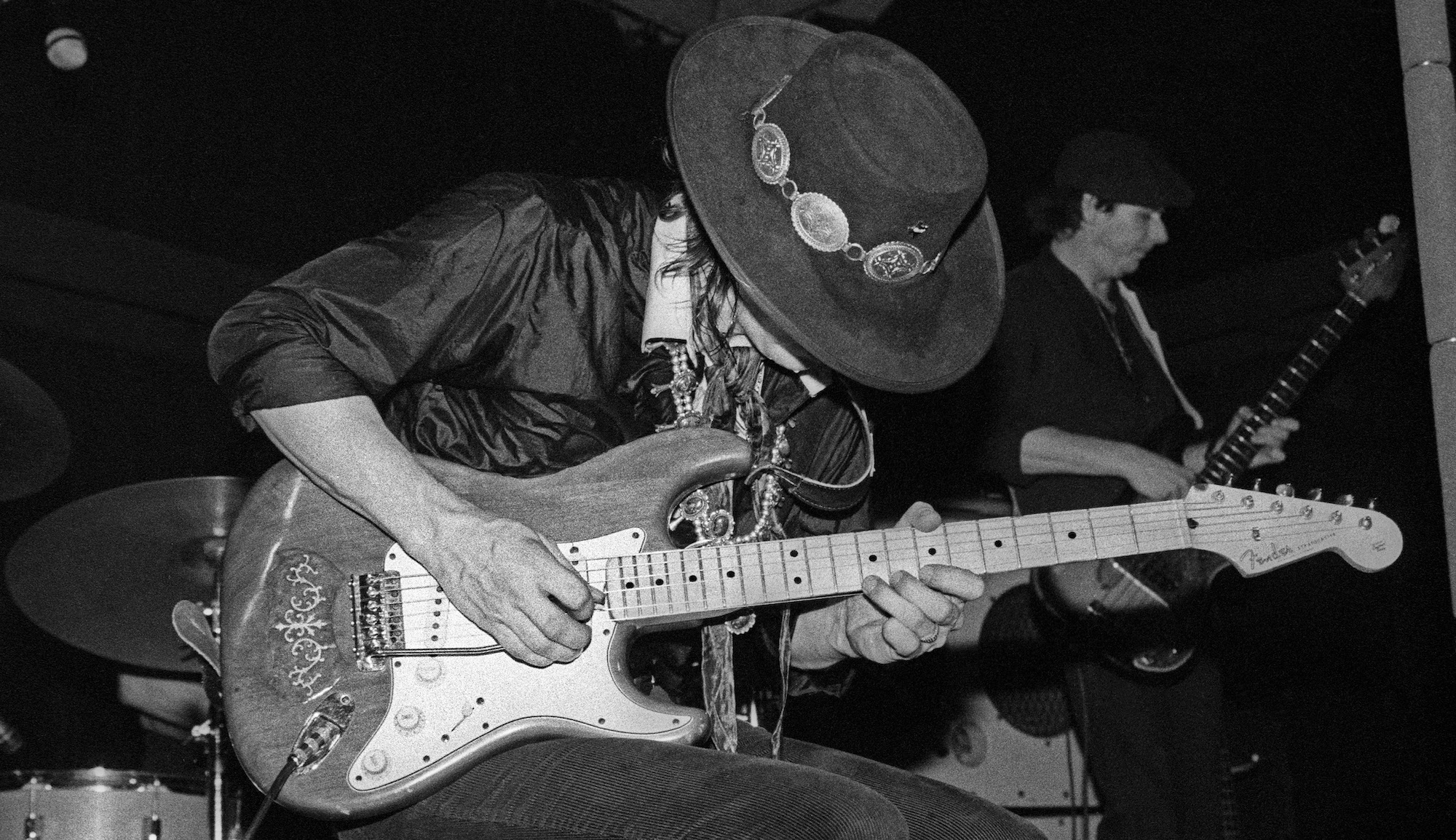

Do you have any guitars not in the Strat family?

“I have a 1958 Gibson dot-neck ES-335 and a '48 Airline that's a bit smaller but the same shape as a Barney Kessel Kay. It's got three pickups with a 4-position toggle switch – bass, middle, treble, or all three. I've got an old Rickenbacker prototype with a flat top, and I'm giving that to Hubert [Sumlin]. And I've got this 1928 National that belonged to Blind Boy Fuller. Byron Barr, my guitar roadie, gave it to me.

“Sometimes I'll pull it out at the end of a set and sit down and play Rude Mood or a little slide. I'd planned on using it on the last record, but we got sidetracked and never got around to it.”

Do you play slide in open tuning?

“I usually just tune up the G string to Ab and leave everything else the same.”

How did you go about recreating the sounds you heard on Hendrix's records?

“You just keep listening and trying to find the sound, because it's in your hands as much as anything. It's the way you play. There are different techniques to playing everybody's styles, and it's not just necessarily the amp or the guitar. It's the way you pick, the way you hold the guitar.

“For instance, T-Bone [Walker] played like this most of the time [holds guitar horizontally, away from his body], and the tone is different when you play that way. Can you hear the difference? [Holds guitar against his body and plays the same licks – gets a bassier tone]. It's the way your fingers hit the strings, and you're more prone to pick closer to the neck when you hold the guitar like T-Bone.”

Your '59 Strat has the vibrato bar anchored off the bass side of the bridge. Did you set it up that way because Jimi Hendrix's guitar bodies were upside down?

“Well, I started listening to people and noticed that when Otis Rush used one, he had it on the top – he played upside-down. And Hendrix had the guitar upside-down, except he strung it regular. It seemed to me that the people who did that the best had it on top, so I moved mine. Sometimes it does get in the way. I've had it tear my sleeve halfway off.”

So instead of working it with the little finger of your picking hand, it lays right in the middle of your palm.

“Yeah, and I've got the springs set up so I couldn't move it with my little finger anyway. It's pretty tight, with four springs tightened all the way up. That's how I can do Third Stone From The Sun and still be in tune. See, I have my old Strat set up where it won't go up at all. On my newer Strats, the vibrato handles are on the bottom, in the regular place. The orange one and Lenny, the brown one, both of their vibratos will go pretty far up and down as well, and they're set up a lot lighter.

“All the guitars have personalities of their own and feel completely different. They each have different sounds. Like the brown one sounds real good for jazzy-type things or Lenny. It's a '63 or '64 that my wife, whose name is Lenny, found for me.”

What about the old beat-up one?

“That's my first wife [laughs]. The new one with my name on the fretboard, I call Main, for main guitar. It's a Hamiltone, build by James Hamilton of Buffalo, New York. It's basically Strat-shaped but a little thicker, and the construction of the neck is pretty much like a [Gibson] Super 400, except it goes all the way through the body. So the vibrato is on the neck, basically – dead center right there. You can pop the low E string, and the whole guitar has this reverb you can hear even without an amp, because of the springs being in the neck.

“It's got an ebony fretboard that's the same width as my beat-up '59, and then they added binding on the outside of that, because I have big hands and I always play barre chords with my thumb wrapped around. What happens a lot of times is my thumb will end up pushing the low E string accidentally. So the wider neck keeps me from doing that.

“The pickups in there now are EMGs with a little computer chip preamp in them, so there's a battery in the guitar, of course. I like that a lot. They say that the battery will last six months, but I can hear it going down – you can hear it in the tone; it gets fuzzier, like it's straining. When it's got a brand-new battery in there, it sounds clear as a bell, and smooth. It'll sing to you.”

I like rosewood necks usually, because for one thing, when you sweat, you don't get blisters. It seems like the finish on a maple neck gets hotter and there's more friction

You've also got a white Strat with three Danelectro "lipstick tube" pickups.

“That was put together by Charley Wirz at Charley's Guitar Shop, Dallas, Texas. He also gave me the yellow one with the pickup in the bass position. That one is hollowed out from the neck to the bridge, because the guy from Vanilla Fudge had put four humbucking pickups in there. It's got a pretty cool tone. Charley then came up with the design for the white one with the Danelectros. He also found me the orange 1960.

“All of the Strats have bass frets. I get them from Gibson, or I use Dunlop jumbo bass frets, the biggest ones I can get. I don't have to replace them twice a year, and there's a lot more sustain. It's a lot easier to get under the strings when you use big strings like I do. You can work yourself to death with those little frets. Instead of the note fading out when you bend a string, it'll get bigger when you bend with the jumbo frets.”

Do any of your Strats have maple necks?

“Yeah, Lenny does. It's got a real clear tone, and the pickups are microphonic – you can hear it when you hit the pickguard. But when you play it soft, it sounds great. When I first got the guitar, it had a rosewood fingerboard, but it was thinner, and that bothered me. So I put a copy of a Fender maple neck on there that Billy Gibbons gave me.

“I like the rosewood necks usually, because for one thing, when you sweat, you don't get blisters. It seems like the finish on a maple neck gets hotter and there's more friction. As hard as I play and as much as I sweat, I get sore enough as it is. There's a fatter sound on the rosewood, as far as I can tell; it's not as bright. The ebony fretboard seems a little bit clearer, but it's fat, too.”

Which guitars have you recorded with most?

“Lenny on the song Lenny, and everything else has been the '59. I'd like to record with the one with the Danelectro pickups; I like it a lot.”

How do you do some of the tricks you do onstage – like getting the whole guitar behind your back so fast?

“As I'm spinning around, I'm taking the strap loose and the guitar pivots behind my back, and then I rehook it behind my back. It's really playing the same way, except you've got to hold the guitar out a little bit, and you just can't see as well.”

In Third Stone From The Sun, you have the guitar laying on the stage while you straddle it, pulling up on the neck with one hand and on the wang bar with the other.

“Yeah, I wouldn't recommend that anybody do that on their 335 [laughs]. A Stratocaster's a pretty tough thing, though. Then I figured out how to get the guitar to rumble. I put it on the middle pickup, turn the tone knob down, grab it by the wang bar, and just shake it on the floor.”

Do you use any effects besides the wah-wah on the Hendrix tunes?

“Just an Ibanez Tube Screamer. I have Univibes, but I don't use them. I use the Vibrotone for that effect. I don't have any straight distortion devices; I use the Tube Screamer for that.”

Who works on your guitars?

“Charley Wirz or Michael Stevens in Austin, depending on who's available and what I'm having done. Certain things, both of them do very well; other things, one of them does better.”

Do you string all the Strats the same?

“Yeah, I use a .013, a .015, or .016 depending on what shape my fingers are in, .019 plain, .028, .038, .060 or .056. If I go down to an .018 on the G string, it feels like a rubber band to me.”

Do you have 3-way or 5-way switches on the Strats?

“5-way. I use all the positions for different tones.”

With the amount of amplification you use, do you still pick fairly hard with your right hand?

“Yeah, terribly. That's just how I play. Sometimes I literally pull the strings off. I can deaden a set of strings completely after one set, because I play 'em hard and do a lot of this – [snaps bass string] – to get bottom notes, like Albert Collins. Sometimes, though, I play really soft. That's probably the best Albert King tone I can get.”

When you got the '59 Strat, was it as beat-up as it looks now?

“[Laughs] It wasn't in real good shape. You could still get a jar of model car paint and go around the edges to make it look decent, but that continued to wear off. You asked if I pick hard – well, look at the top of the guitar [which is worn away a good 1/4"]. That's from picking.

“It's gradually sounding different, because I let it dry out too much. I bet if I start oiling it up, it'll start fattening up some. The body is a '59, but the neck is a '62, I believe. In the body, it says, 'LF.59.' I came to find out that was Louis Fuentes, not Leo Fender. But Louis Fuentes was a good cat. You never heard a Stratocaster sound real meaty like that one.”

The tendency on the part of most white blues-rock artists has been to eventually drift more towards mainstream rock.

“We try to keep it going in both directions. There's no reason for us to leave behind what we've got, you know, but there is a good reason to expand on it. I'd like to keep it as a trio, keep that identity, but I have nothing against playing with great horn players or keyboard players or other guitar players – or more than one drummer, even.”

I just look for things that sound right

Stang's Swang is still blues, but it's a departure from the type of stuff you're known for.

“I wrote that four or five years ago. I like guys like Kenny Burrell and Grant Green a lot. I like Django Reinhardt a lot, too, and Wes [Montgomery], of course.”

What's the turnaround on that song – IIVs?

“I don't know. I don't know what key I'm in sometimes. I just try to listen.”

Are you completely self-taught when it comes to any theoretical vocabulary?

“I don't know any of that stuff.”

What about the chord voicings you use?

“I just look for things that sound right.”

So if you're playing something like, say, a diminished 7th...

“I don't know it. I almost learned how to read chord charts doing some of those Bowie things. But as soon as I learned how to read the charts, they took the charts away. Most of the time, I'd listen to a couple of run-throughs while he was doing his vocals, to get an idea of where the song was going. Then I'd figure out in my head where this Albert King lick or that Albert King lick would fit [laughs].”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Dan Forte worked at Guitar Player for six years between 1983-89, where he interviewed Stevie Ray Vaughan, Mark Knopfler and George Harrison among others, before becoming Editor At Large at Guitar World. He is currently Editor At Large at Vintage Guitar magazine.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened