“Stevie Never Got To Have a Family Or Anything Like That. I’ve Been Blessed”: Jimmie Vaughan Opens Up About His Brother

The Texas blues veteran reveals his musical inspirations and talks ‘Family Style’ in this insightful interview.

Jimmie Vaughan’s reputation as a premier electric guitar slinger stretches way back to the ’60s, when he found regional success in Texas, crossing paths with many of the big names of the time, including Jimi Hendrix.

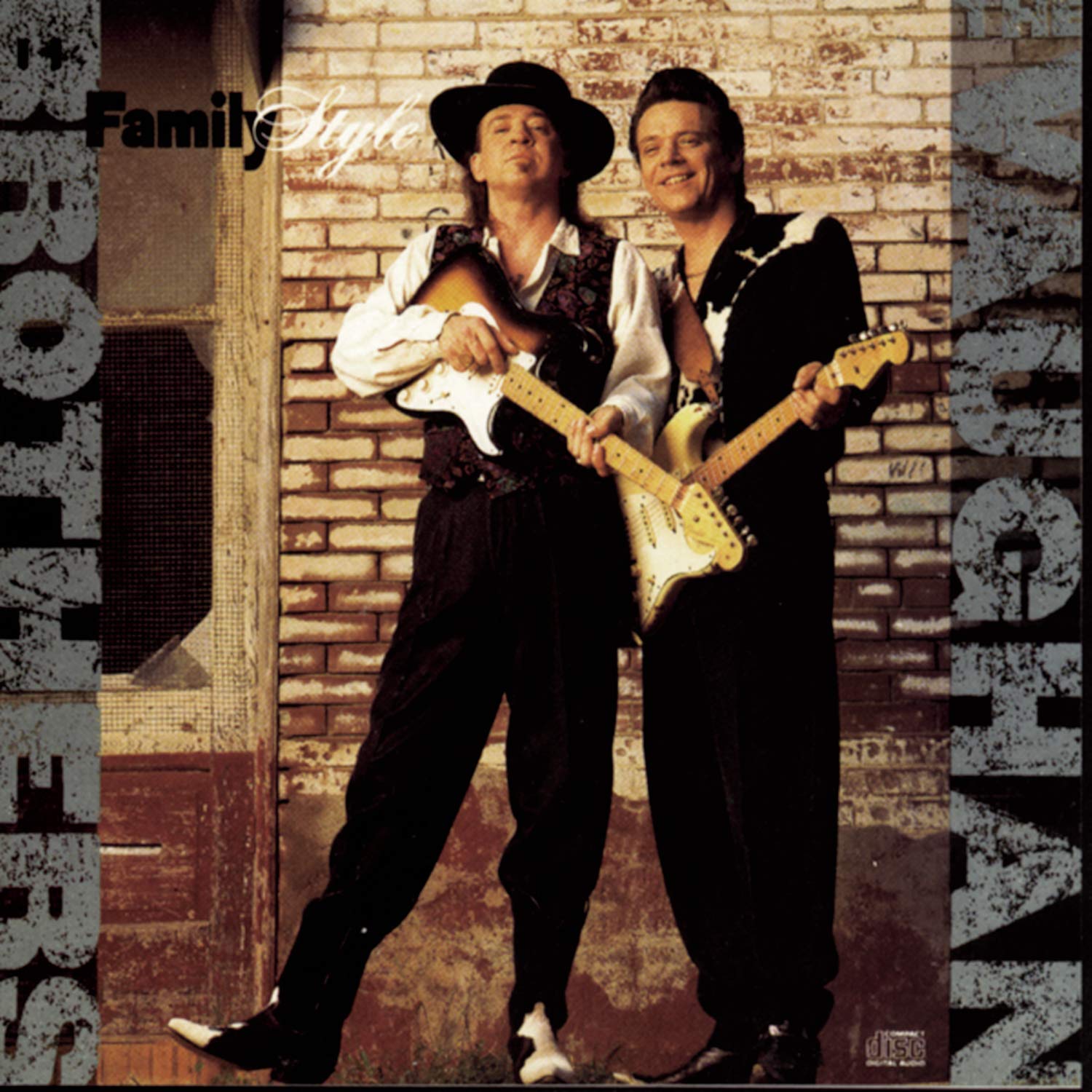

For most listeners outside Texas, Vaughan first came to prominence in the late ’70s as the killer guitarist in what was arguably the first really cool blues band in eons, the Fabulous Thunderbirds. After seven albums of no-frills, down-and-dirty blues guitar, Vaughan left the group, made an album with his brother Stevie – 1990’s Family Style – and settled into a solo career playing blues-rock songs of his own and mixing in acclaimed collaborations with numerous blues luminaries, including a pair of albums with Omar Dykes.

In recent years, though, Vaughan has made several return visits to the music he loves best: the rare and frequently arcane recordings of R&B artists he grew up with, like Jimmy Reed, Jimmy Liggins, Bobby Charles and Nappy Brown.

He released his first R&B covers album, Plays Blues, Ballads & Favorites, in 2010, and followed it up in 2011 with Plays More Blues, Ballads & Favorites. His third album in the series, 2019’s Baby, Please Come Home is a righteous celebration of blues, while last year saw the release of The Pleasure's All Mine (The Complete Blues, Ballads & Favorites Sessions).

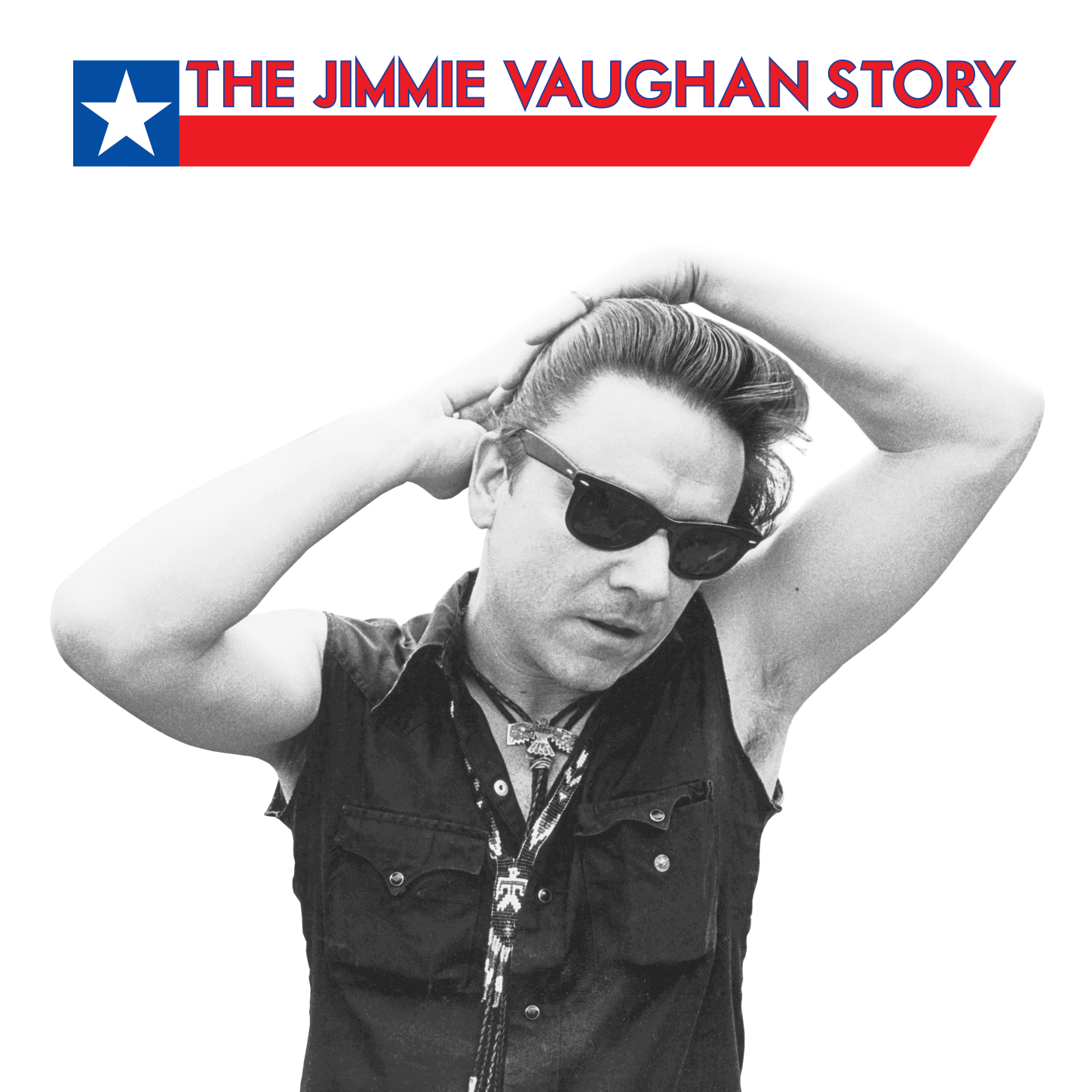

Earlier this year, fans were treated to The Jimmie Vaughan Story – an encyclopaedic 96-track 5-CD epic release. Showcasing Jimmie’s distinctive take on the blues these recordings comprise rare and unreleased gems from the initial part of Jimmie’s career, including his early bands Storm and The Fabulous Thunderbirds.

Back in 2019, GP caught up with the man himself shortly after the release of Baby, Please Come Home.

Baby, Please Come Home is your third album of blues covers. Is this the plan going forward?

At this point, I’m just doing stuff that I like. That’s the truth of it. I just like those songs. Basically, when I write my own stuff, it sounds like the same kind of thing, and nobody knows these songs. And I really enjoy making this music with my band. We get to play blues, we can swing, and we can rock out.

Are you no longer interested in writing original material?

Well, if you’re gonna write, you have to get up in the morning and write something every day and really work on it. I am gonna make an album with songs that I’ve written at some point, but this is where I’m happiest at the moment.

It’s interesting to hear how your vocals have developed over each album and how you’ve really found your voice.

For years, I didn’t want to sing, until finally I got into a position where I had to sing or go home. When I was a kid – maybe 15 or 16 – you couldn’t tell from my playing how old I was. I think my voice has gotten deeper, maybe partly from getting old and also from just doing it.

I think when you play for many years, your phrasing will always change as you try to reproduce the stuff that you hear in your head.

Jimmie Vaughan

Does the singing change your phrasing on the guitar?

I think when you play for many years, your phrasing will always change as you try to reproduce the stuff that you hear in your head. I always think of myself as a sax player. I like the way the sax player expresses himself, and, especially if you’re singing, you kind of express your song in the voice, then you go back and do it on the guitar. I suppose that makes it sound pretty simple!

Guitarwise, are you still using your signature Strats into Grammatico amps?

Yeah. I use Fender Bassmans as well. A Grammatico is really just a hand-wired Bassman. I like the way 10-inch speakers sound. I used to really enjoy the Matchless, but they quit making them. It’s hard to beat a Fender Bassman though.

You keep your guitar volume low but run your amp high.

That “hots” the amp up, gets it on the edge. That’s the sweet spot where you get the best from the amp. I like it where it sounds like it’s going to blow up. It sounds present.

From the first Fabulous Thunderbirds, it was obvious that you put thought into the spaces between notes – that what you didn’t play was as important as what you did play.

That was a “call and response” style that I learned from my heroes, even those who didn’t play guitar. When you first start to play as a kid, you want to fill up all the holes, but then you realize that the reason why you like certain people is not only because of their tone but also their phrasing.

Just the idea that you can have phrasing that sounds like jazz or blues is pretty intriguing to me. When I hear a sax player like Gene Ammons – he’ll play a phrase and then he’ll wait. And it’s the wait that gets you. That space to breathe. That space to give you time to feel what you just heard.

When I hear a sax player like Gene Ammons – he’ll play a phrase and then he’ll wait. And it’s the wait that gets you. That space to breathe.

Jimmie Vaughan

You had a great way of sitting in behind the harp on Kim Wilson’s solos and not taking up too much space.

I listened to Jimmy Rogers with Little Walter and Eddie Taylor with Jimmy Reed… All those guys. I loved the way they play. I’m a real big fan of that approach.

The first four Fabulous Thunderbirds albums were in a more traditional blues vein. Starting with Tuff Enuff, the music became more mainstream and the group had its greatest success.

Tuff Enuff was more rocky, but it was still true to what we’d been doing. We didn’t feel like we changed that much. The increased level of success had its good and bad points: You never get to come home, and you have too many gigs. Life starts getting in the way of all that.

We did have a fabulous time though, ’cause we were doing what we wanted. You know, when we started out playing covers of old rhythm and blues songs, record companies would say to us, “You can’t get a record deal. That’s a bunch of old shit that no one wants to hear.” We did it anyway, and we had to fight hard each step of the way.

So when we made Tuff Enuff, we just did it the way we wanted to. And we made them take their words back.

You really introduced a lot of those old blues players from the Excello label to a wider audience. Was that deliberate?

Well, what a great thing to do if we could do that. We were just playing what we wanted to hear. I never get tired of the Excello players: T-Bone Walker, Buddy Guy, Jimmy Reed…all the guys I’ve always loved.

Given the demands of success, did you split from the T-Birds because you felt burned out?

What happened was that the record company kept asking me and Stevie, would we do an album together, and we’d been thinking about it since we were little kids. We’d play at home for the guests. My dad would say, “Go get your guitars!” and we’d play for the people, and the guests would say, “Well that’s pretty good, kid. Maybe you guys could make a record someday.”

We ended up making Family Style. Then Stevie got killed before it came out, which really screwed everything up. I didn’t know what in the world to do, and everybody was just flipped out. I still can’t believe what happened, and I’m talking about my feelings and the way it still feels. It took me a long time to really get back. He was my little brother.

When we were kids, I was supposed to get him to school and back. Protect him. So it felt like I’d failed, even though there was nothing I could do about it.

Jimmie Vaughan

When we were kids, I was supposed to get him to school and back. Protect him. So it felt like I’d failed, even though there was nothing I could do about it. It took me a while to process everything.

Stevie never got to have a family or anything like that. I’ve been blessed. I have a wonderful family, I get to play guitar, I have a great band. I have all the wonderful things in life.

Had Stevie not died, do you think you would have followed a very different path and perhaps worked more closely with each other on a regular basis?

I think we would have done a tour and probably another album. But it’s all speculation. I might have done more with the T-Birds as well. It wasn’t like I was trying to quit the group to be with Stevie or he was leaving his band. This was just something different for us. We were just trying stuff.

Afterward, you came out with your first solo album, 1994’s Strange Pleasure. Did you feel under pressure to match the T-Bird standard once you were out on your own?

Well, you always feel pressure to try to make a better record next time. You have to follow yourself. What happens is, once in a while you just screw around with ideas and you get something really good. But you don’t know how that happens, ’cause if you could figure it out, you would do it every time.

It’s that “lightning in the bottle” moment.

Yeah. The gypsies call it duende. If you can find that in yourself, that’s the fun of it. I just love to play so much. If you keep playing everyday, and you keep working on it and your sound, I think it comes to you.

Buy Family Style here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened