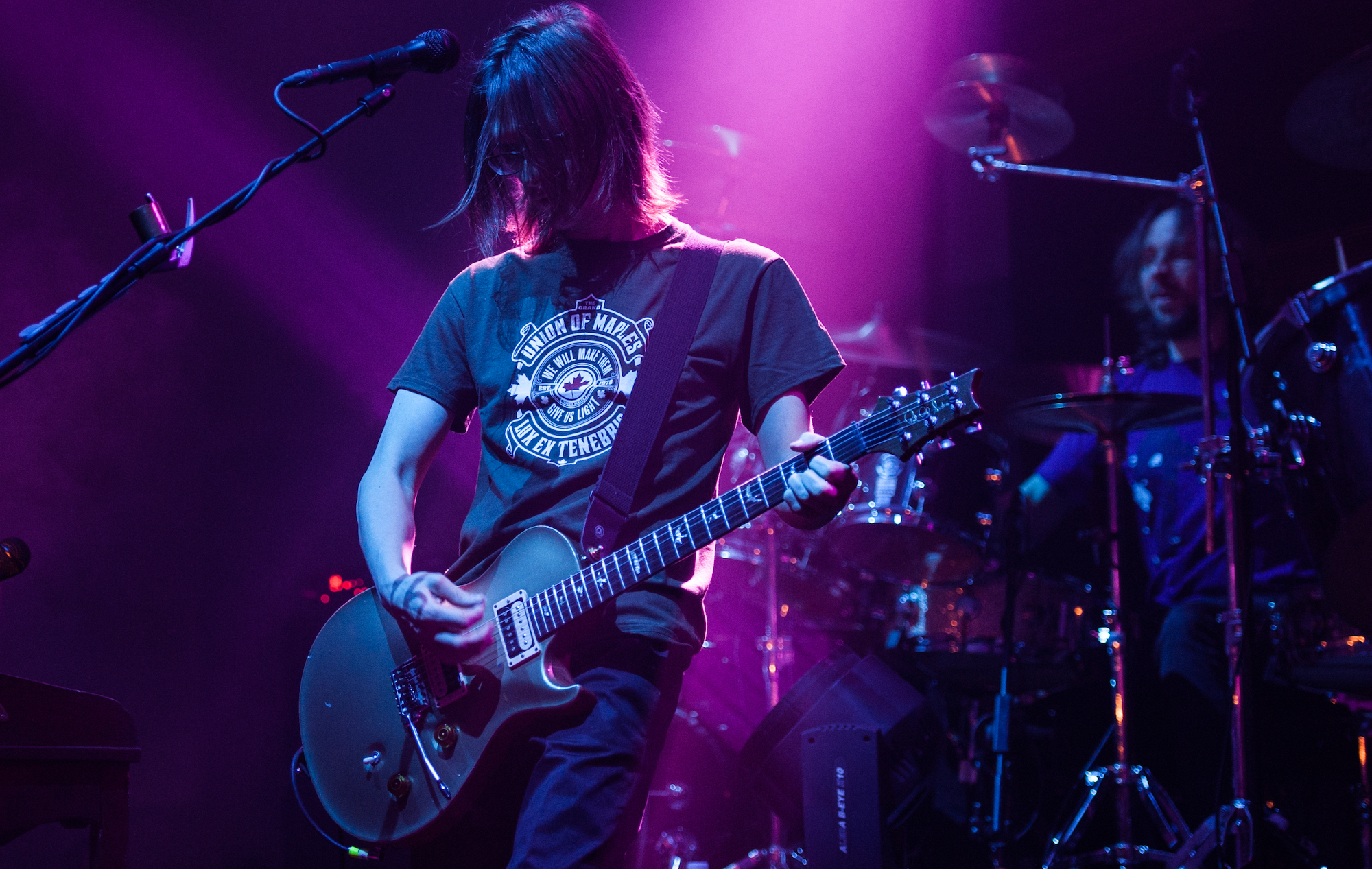

Steven Wilson: "If You Play Something Really Fast, it Doesn’t Really Convey Emotion; it Just Reduces Guitar Playing to an Olympic Sport"

The Porcupine Tree frontman and guitarist discusses his complicated relationship with the prog-rock genre, and the band's ferocious comeback album, 'Closure/Continuation.'

Steven Wilson bristles at the use of the term prog rock to describe his music, both as a member of Porcupine Tree and as a solo artist. But in fact, all that genre’s familiar tropes are present: complex time signatures, wide-ranging stylistic shifts within songs, intricate riffing, and a high degree of technical ability.

Regardless of categorization, the new Porcupine Tree album, Closure/Continuation (Music for Nations) is as strong a record as you’ll hear all year, whether it’s considered from the perspective of classic rock, pop, or, indeed, progressive rock.

Thirteen years have passed since Porcupine Tree issued their last album, 2009’s The Incident. In the intervening years, Wilson has pursued a highly successful solo career, collaborated with a diverse range of artists, and become the go-to guy when classic rock albums need a remix.

Closure/Continuation arrived out of the blue for fans of his work, although Wilson and the band’s other two members, keyboardist Richard Barbieri and drummer Gavin Harrison, had been exchanging ideas between themselves for many years. It became clear to Wilson that what they had created was strong enough to compete with the best of his work both inside and outside of the band, and consequently, Porcupine Tree sprang their 11th album on an unsuspecting public in June 2022.

Not only has Wilson been working hard on creating the songs for Closure/Continuation and producing the album, but he’s also found the time to write his autobiography, Limited Edition of One. It is an honest and revealing insight into how Wilson operates, his background, and how he views his place in the musical firmament.

In conversation, Wilson is eloquent and voluble, and unafraid to offer an opinion which might not sit easily with fans’ expectations of him. But any interview with him is all the better for his candid and forthright views.

The last Porcupine Tree album was released in 2009, and when you talk about Closure/Continuation in your book, there’s a suggestion that this may be the band’s last album. Do you still feel that way?

"The album’s title reflects the fact that we’re not definitively sure one way or the other. As I say in the book, it all depends on whether we think there’s something different that we can do next time or if it’s just going to be more of the same kind of thing.

"I discussed this with Richard last week when we were doing some press, and we agreed that if we could do something different, then maybe there would be scope for another album, but that’s just a notion at the moment. There’s certainly nothing guaranteed. I don’t think we’ll tour as a band again though, once we’ve completed the dates that we’ve got planned to promote the current album."

When you were exchanging ideas with each other over the years, was that with the intention of ultimately making an album, or was it purely for the joy of creating music?

"I think a bit of both. There’s no reason why you can’t have joy in creativity and also have one eye on the idea that you’re going to make a record. I grew up loving records and always wanting to release records, so I’m always thinking in terms of what could open side one, what could close side two. So right from the beginning, I was always thinking about those kinds of considerations.

"There was never any guarantee that we’d release the music though. One of the key things about what we were doing was that it was made in a complete vacuum; nobody knew that we were doing it. We didn’t tell any management or record labels. The potential was always there that we might decide we hadn’t created anything new and we wouldn’t release it. The fact that we didn’t feel that way and thought we’d made a very distinctive Porcupine Tree album was a great bonus.

"One of the reasons there is a new Porcupine Tree album is that I’ve been able to let go of the control I’ve always exerted over the band, because I’ve now got an established solo career, and a pretty successful one. What was different about this record was that I felt able to collaborate with the guys on the songs and also able to defer a bit of the responsibility to them, and enjoy that process.

"I always used to feel slightly frustrated when we made the earlier records, but it was much easier for me this time. I’ve been able to enjoy the collaboration, and I think that is why it has come out sounding so fresh. I think this album is one of the most significant albums that I’ve made."

The opening track, “Harridan,” which was the first to be released from the album, is almost the quintessential progressive-rock song, in the truest sense of the word, given that it covers so many stylistic bases.

"Yes that’s exactly right. When someone asked me recently which song I’d pick to showcase the band, I said 'Harridan' for the very reason you just gave. It has a bit of everything: a funk-bass opening, heavy riffing, acoustic parts, polyrhythms, an anthemic chorus, and a long sprawling arrangement. All the stylistic aspects of the band are encompassed within it.

"That song is my idea of what progressive rock should be. Often when people think of progressive rock, it’s not the kind of music that I’d like to listen to or play – it’s a very old-fashioned kind of thing. The reason that it opens the record is because it is almost a manifesto for what the band is about."

Did you play bass on that track?

"Yes, I played all the bass parts on the album. I’ve always been a slightly frustrated bass player, with an ego too big to be the bass player, because I want to be out there at the front. I think it goes back to my love of Chic and Donna Summer, which was very much about the great bass lines.

"I wrote a lot of the album with Gavin on drums, where I was coming up with bass licks first. I will happily acknowledge that I play bass kind of like I play guitar: I play melodic stuff and I play a lot of chords as well, the things a 'proper' bass player probably wouldn’t do. Maybe one of the reasons the record sounds different from other Porcupine Tree albums is that it was largely based on how I play bass."

You said in the book that you feel a bit of a fake doing interviews for guitar magazines. But here we are.

"I know. [laughs] And I do a lot of them. It’s very flattering that people think of me as a guitarist, but at the same time it always feels slightly awkward, as I can go for months on end without picking up a guitar until I need to play it for a song. I know that’s very different from all of the proper guitarists that practice every day and have a real relationship with the instrument. I’ve never had that."

Who were the guitarists that inspired you?

"I was never a fan of the shredding thing; I was always a fan of guitar players that would play one note and it would really touch your heart. That would obviously have been David Gilmour and Peter Green. But also, in the ’80s, I grew up with a lot of post-punk music, so I loved bands like the Cocteau Twins – Robin Guthrie would play one note, and then he’d spin off into a chain of delays and reverbs and chorus effects. I loved that.

"I’ve also always loved the idea of using the guitar in a much more textural way – the shoegaze aesthetic. Robert Smith was another guitarist whose work I really enjoyed. I never listened to the shredders like Eddie Van Halen, and of course, I got into trouble when I was doing an interview just after he died and I said that his death didn’t mean a lot to me because I’d never listened to his music.

"It wasn’t that I didn’t respect his abilities, only that as far as his music was concerned, it wasn’t something that I ever listened to. I’ve always thought of the guitar as a part of the whole song."

Your own soloing is always very much a part of the song, and often hangs on to a handful of notes and really gets the most out of them.

"Well, the reality is that I can’t do it any other way. I can’t do the shred thing even if I wanted to. It’s not like Picasso, [he] was a brilliant painter but chose to paint in a primitive style; that’s not me.

"Even if I could play fast, I probably wouldn’t choose to do so. For me, as a songwriter, the guitar solo is an extension of what the vocal is doing. What’s a vocal if it isn’t the emotional heart of the song? I’ve said this before, but if you wanted to communicate something to somebody with your voice, you’d speak slowly, with a lot of emotion. You wouldn’t speak at 20 words a second. That doesn’t communicate anything.

"If you play something really fast, it doesn’t really convey emotion; it just reduces guitar playing to an Olympic sport. For me it’s about saying one word and making it count."

How much do you work out what you’re going to do ahead of recording the song?

"I do the Gilmour thing: I improvise a lot, then I comp the best parts, like he did on the 'Comfortably Numb' solo. I find the best parts from each pass and comp them together. I don’t always know what I’m doing beyond having an instinct for what the feel should be. Sometimes I’ll look at the final comp and think that I could play that all the way through again and re-record it, which can sound a little more fluid."

When it comes to writing songs, are you actively experimenting with different time signatures, or is it part of the organic creation of the song?

"I think it’s a bit of both. Gavin has written books about rhythmic illusions and polyrhythms; he’s really good at coming up with interesting, unusual rhythmic ideas. The songs in unusual time signatures are often based on an idea that Gavin has come up with, and then I’m presented with the 'problem' of creating melodic and harmonic structures to complement what he’s created, and to make it sound natural.

"The essence of the band has always been the combination of Gavin’s distinctive rhythmic sensibilities, Richard’s interesting sound design and textural approach, and my singer/songwriter desire to make things into a viable song. Those are a big part of the band’s DNA."

Have you ever read any of the books written about you, and was Limited Edition of One an attempt to put the record straight?

"I’ve not read any of them. I feel uncomfortable about the very notion of being confronted with the way that people perceive you, the way they’ve interpreted what you do. After many years of so much disinformation about me on the internet, which partly arose because I’m so private and didn’t go out of my way to correct inaccuracies, it became irritating to read so much that was incorrect.

"I think I always knew that any books written about me would be based on the stuff that’s already out there. With my book, I tried to write about the things that I knew nobody knew about."

There are a lot of lists in the book: your favorite books, films, records… I found it interesting that you were a big fan of Abba and Donna Summer in your early years, and it’s music that you still love now.

"That was one of the reasons I wrote the book, and one of the main themes. I tried very hard to be a musician that exists outside this notion of genre, and yet the industry and fans will relentlessly try to categorize you in a particular genre. I grew up listening to everything from post-punk and industrial to disco, and I loved it all.

"It just so happened that one of many projects that I started when I was young was the one that took off. That was the one where I was indulging my love of ’70s progressive-rock music.

"If it had been my band No-Man that had taken off, then I’d have been playing synth pop, or it could have been the work I was doing exploring ambient music. People would have had an entirely different perception of me if success had come from some of the other things that I loved. For better or worse, it was Porcupine Tree that took off, so now I’m the guy that does prog."

Did writing the book give you a new perspective on yourself or your career?

"Yes, I learned so much about myself. I always thought my family background was pretty ordinary, but in recounting the dark things that happened to some of my relatives, I realized that some of those things were pretty fucked up. I can actually trace some of those things through my songs. In much the way that I’ve deconstructed and reconstructed classic albums, I was deconstructing and reconstructing myself.

"I’ve come out the other side with a better understanding of myself, and a little more contentment."

You say in the book that you often lie in interviews. How much of what we’ve discussed is untrue?

"I don’t know. [laughs] I talk so much that I believe my own bullshit. Sometimes I’ll think back and realize I’ve been saying things for years that aren’t true without even being aware of it at that time. I’ve not consciously lied to you, but who knows? Time will tell."

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.

"This 'Bohemian Rhapsody' will be hard to beat in the years to come! I'm awestruck.” Brian May makes a surprise appearance at Coachella to perform Queen's hit with Benson Boone

“We’re Liverpool boys, and they say Liverpool is the capital of Ireland.” Paul McCartney explains how the Beatles introduced harmonized guitar leads to rock and roll with one remarkable song