“I got John Lennon’s Epiphone Casino and played through his amp, Paul got on the drums. It was like we’d been playing together forever”: Steve Miller on jamming with the Beatles, his pre-show warmups, and 50 years of the Joker

Steve Miller beamed as he introduced Christone “Kingfish” Ingram to the audience at a sold-out Jazz at Lincoln Center performance last winter. It was Miller’s seventh annual JALC blues concert, where he presents various aspects of the music’s glorious heritage. This year’s show focused on the future of the blues in the person of Kingfish, and Miller was thrilled to help the 24-year-old Mississippi native expand his reach – and just to jam with him.

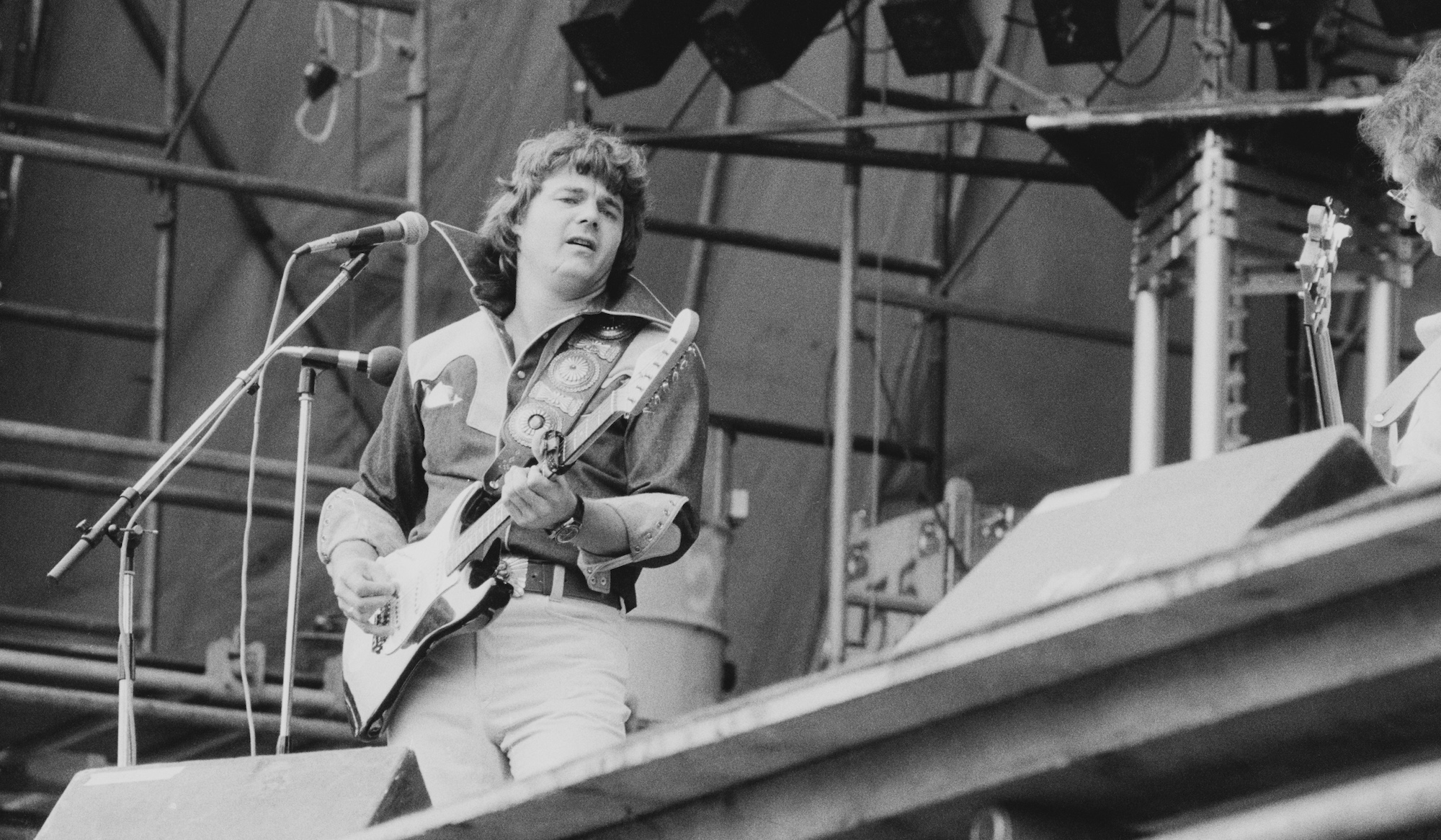

Miller might seem an odd choice for a blues show. He became known as one of the kings of classic rock with a string of mid-’70s hits that dominated FM radio in that decade and again when the classic rock radio format became a force to be reckoned with more than a decade later. But before The Joker, Fly Like an Eagle, Rock’n Me or Take the Money and Run, he was a serious blues aficionado playing harmonica and guitar.

Miller left the University of Wisconsin a semester shy of a degree and in 1965 moved to Chicago, where he began playing with the music’s masters – including Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, and Otis Rush – and with other young white practitioners, like Mike Bloomfield and Paul Butterfield. He also learned to be a pro there, playing six nights a week.

But Miller’s real success came when he moved to San Francisco in 1966 and started recording for Capitol Records.

He thought he had hit the big time when Paul McCartney played bass and drums and sang backup on his 1969 single My Dark Hour. That went nowhere, and by the time Miller entered the studio to record the last album of his Capitol deal in 1973, he was furious at the label for not doing more for him. “I was so angry at Capitol Records for lack of support or having a clue,” he says. But Miller soon got the satisfaction he deserved.

He recorded his 1973 hit, The Joker – the title track to his album of that same year – in 30 minutes, and it became his first number-one single. With it, Miller established a new paradigm, displaying the wit of a comparative literature major, the soul of a blues man, and the pop sensibility and studio savvy of Les Paul and Mary Ford, who were not only studio pioneers but also Miller family friends.

Miller followed up The Joker with two more massive albums, 1976’s Fly Like an Eagle and 1977’s Book of Dreams. It’s no wonder The Steve Miller Band’s Greatest Hits 1974–’78, is one of rock’s best-selling albums.

With J50: The Evolution of the Joker, Miller has delivered a 50th anniversary celebration of The Joker that includes outtakes and alternate versions of its tunes. Compiling and penning an extensive liner-note essay for the set made Miller look back at his career, something he says he rarely does. It makes this a good time to catch up with the classic rock legend, who at age 80 is still playing and singing terrifically.

You did a great job on J50, which really tells a story about not only the album but also the era and your entire career to that point, and even beyond.

“Thanks. That’s all due to my wife, Janice, who is a musicologist. Over a decade ago, when we first started dating, I showed her my warehouse in Idaho, where I lived for 20 years. I was ready to get a shredding truck and trash it all, but she was drooling over the 20,000 square feet of stuff.

She got it all digitized, listened to 600 hours, then said, ‘I pulled 184 things I want you to listen to’

“I fought it all the way but was suddenly looking through my checkbooks from 1971 and ’72, which I used to pay for the entire life of the band, and started reconstructing it. There were walls and walls of music on technology we no longer use: cassette tapes, DATs, eight-track recordings…

“She got it all digitized, listened to 600 hours, then said, ‘I pulled 184 things

I want you to listen to.’ I had carried a four-track tape recorder around in a giant suitcase and recorded all my gigs on it, then took the thing back to the room and worked on songs.

“I could play a guitar part and three vocal parts and work out ideas. She found footage that I’d forgotten all about from 1972, when we had hired a girl with a 16-millimeter camera. I look like I’m 12 years old, but there I am driving the shittiest rental car you ever saw and staying at the Holiday Inn. There’s footage of shows, stuff from my hotel rooms and in the car. We found a film editor to make it make sense, and it’s really great.”

So you’re happy now that it’s done?

“I think Janice did a phenomenal thing with it, and I am very happy, but my history is ongoing. I just finished doing 45 cities. I’m recording and will have new music out in 2024 – one of three projects I’ve been working on. I’m a late bloomer, and people are paying more attention to me than they did 10 years ago, so I’m looking ahead, not behind, as much as I can.”

Your serious success started with The Joker, the last album in your Capitol deal. Why were you so mad at them?

“I’d just done 60 cities, and they didn’t have any albums in any of them. I was ready to beat them with my fists. When I gave them this album, I thought it was the end of our relationship. We had a playback for the executives, and one 23-year-old kid who had no power in the company said, ‘I think The Joker is a hit single.’

I was playing it in my show-opening solo acoustic set, but people were just going nuts right away, so we added it to the band set, and it just took off

“I looked at him and said, ‘Listen, I don’t care about hit singles. Just have these albums in stores when I’m in town.’ The Joker was picked as the single and the album title, and – ding! ding! – it went viral on its own.”

As much as you didn’t expect The Joker to be a hit, it’s a really interesting song, with a lot going on. It’s quite different.

“Yes. I worked on the music a long time, and knew exactly how I wanted it to go and finally got the lyrics together in the studio, and it all finally fell together. But it didn’t sound like anything on the radio.

“I was playing it in my show-opening solo acoustic set, but people were just going nuts right away, so we added it to the band set, and it just took off. The Joker was on the air two times an hour, 24 hours a day, for about a year and a half.”

And that completely shifted your career.

“It set me up. What really changed my career was the six singles that followed. And that was by design. When I worked with the Beatles in 1969, I learned a lot. They were finishing up their records and breaking up – and they had 40 hits in the can. How the hell did you do that? I wanted to try.”

Paul McCartney played on your Brave New World album. How did that come about?

“I was working at Olympic, and they were mixing [the 1969 single version of Get Back] there with Glyn Johns, whose house I was staying at. Glyn took me to George’s house, who invited me to the sessions, where I watched Lennon and McCartney sing Get Back – which was done in like 12 minutes. I was thinking, ‘Holy shit. I can’t believe I’m here.’

“The next day they were going to record, but John and Ringo didn’t show up. So, I was sitting there with McCartney, Harrison, and Glyn, who suggested we play some music while we waited. Paul starts playing Lady Madonna on the upright. Unbelievable. George is sitting around playing guitar. I get Lennon’s Epiphone Casino and am playing through his amp, Paul gets on the drums, and it’s like we’ve been playing together forever.

“We’re playing blues and George got bored, because he’s sort of a barre-chord, straight guy. I showed Paul the lick for My Dark Hour – which eventually became the opening lick to Fly Like an Eagle – and we were off on the song.

“He played drums and bass. I played guitar and pedal steel and the lead, and we did the background harmonies together. Then he, Linda [McCartney] and I mixed it, all in one day.

“I also watched them mix Get Back, which was number one all over Europe three days later. I’d never seen anything like that. What I learned from that was it’s good to be two albums ahead, but if you do something great at the last minute, you can always lead with your freshest thing.”

But it took you a few years.

“No, man, I learned that in a minute, but if you’re not Lennon and McCartney, it can take a while to achieve! It was immediately clear, even from simple conversation, that they truly were geniuses. It was like, ‘Hey, boys, it’s 4:30. We got the drummer until seven. We need another song…’ and they go into the next room and write a hit.

I just thought, ‘That’s a great riff. Fuck Paul McCartney. I’m doing it’

“How is that possible? The thing that we all saw on the last film [Peter Jackson’s 2021 documentary, Get Back] was what happened to the Beatles when they got sucked into our shitty world: Sit in a bad room, have politics going on, bring your girlfriends… It’ll be a great way to make an album. [laughs] They fell into that same crap as the rest of us. When I watched that movie I felt like I was at work.”

It’s great that you re-used the My Dark Hour riff on Fly Like an Eagle. Did you plan on doing so or just realize that it fit?

“It just worked. I had been so excited about My Dark Hour. I walked out of the studio thinking, ‘Paul McCartney is on my next single – here we go!’ And when they released it, it was like it was dropped from the top floor of the Empire State Building mail chute and went straight to hell. It was gone. Nobody said a word about it. I just thought, ‘That’s a great riff. Fuck Paul McCartney. I’m doing it’ [laughs].”

You said The Joker set you up for the six singles that followed, but you took time off before Fly Like an Eagle.

“Yeah, there was 18 months between them. I was exhausted. Capitol wanted me right back in the studio and I tried but had to say, ‘I really don’t have anything to record. This is a waste of time.’ Two weeks later, I had gotten refreshed and booked some studio time in Seattle, where I had moved. I flew the band into town and they all came and quit! They were just fried. We had played 260 gigs a year, two guys to a Holiday Inn room, no buses, flying everywhere and renting cars. We were burned out.

“I went home and set up a pro eight-track 3M tape recorder in my living room and finally got tunes together. I took Gary Mallaber and Lonnie Turner [drummer and bassist, respectively, for the Steve Miller Band] into a studio and we cut 25 tracks in 11 days as a trio. The guitars sounded big and fat, recorded on 16-track. I mixed it down to an eight-track tape recorder, stereo, left and right sound, took it home and finished all the songs on Fly Like an Eagle and Book of Dreams – all the vocal parts, guitar parts, Echoplex parts, and keyboard parts. I wanted everything to feel spontaneous, not perfect.”

So those two albums were recorded together, mostly in your house?

“Yeah. I only went back in the studio to mix. There was about 25 songs and

I thought, ‘Great! Twelve singles!’ But that’s stupid, because nobody sells

12 singles off a record, so I spread them out. And this journey of two albums started fitting together. I’d take something off album one and put it on the other. Then I took it to the studio and mixed Fly Like an Eagle in 17 hours.

“I felt really dialed in. I knew exactly what FM and AM radio needed. My job was to make FM radio sound great, and this record did that.”

You didn’t expect The Joker to be a hit. So what transitioned from that to just the next chapter, where you could dial in to the zeitgeist?

“One thing that really helped was, in the middle of all that recording, I got a phone call from Pink Floyd. They were playing Knebworth and wanted me to play with them. My agent said they offered $25,000, and I told him to turn it down, because I didn’t even have a band and was recording. They wouldn’t take no for an answer, and I kept raising my price and finally said, ‘Tell them it’s $125,000 to make them go away.’ But they said okay. [laughs]

“So I called Cosmo, the drummer from Creedence Clearwater, Les Dudek from Boz Scaggs’ band, and Lonnie and offered them a fistful of dough for a quick trip to Europe. We rehearsed at my house for one day and went over to play for 120,000 people, twice what they expected.

“They put me on at the crappy part of the day – dusk, which is after the lovely afternoon and before it’s dark enough for lights. That’s where they always put the band they’re most worried about upstaging them. I needed something to really rock this joint: Rock’n Me.”

Did you write it for that purpose?

“Pretty much. And it worked! Then I decided to release my best single second, not first. Take the Money and Run got to number 11 with a bullet, and then we released Rock’n Me and it went to number one. You get people’s attention, and then the next thing is even better.”

I did the phone work, and we mimeographed a letter and sent it out to every fraternity and sorority, country club, Boys & Girls Club, church, synagogue, and mosque in Dallas

You’re pretty unusual in being so aware of things like that.

“That’s what you get from doing business with fraternity boys when you’re 12 years old. They’d call to hire our band, then say my price of 75 bucks for three of us was too much money, and I’d go, ‘Well, thanks, man. If you change your mind, let me know’ – and hang up!

“I would never talk to them about their problems or why I should lower my price. We were 12 and I was making $300 a month in 1956. I did the phone work, and we mimeographed a letter and sent it out to every fraternity and sorority, country club, Boys & Girls Club, church, synagogue, and mosque in Dallas.”

Was your business savvy respected or considered crass by the music world in

San Francisco in 1967?

“A little bit of both. We had group meetings, and I gave a copy of my contract to [improvisational comedy group] the Committee and to Quicksilver Messenger Service, because everybody else’s contract was dumb as shit, and they didn’t own anything. But musically, we started bringing James Cotton, Junior Wells and Buddy Guy, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, and all those people out to California, because we needed them!

“I saw a whole bunch of middle-class white kids trying to start rock bands, plus the Chambers Brothers, who were great. When I first saw the Jefferson Airplane, it was guys pouncing around in boots with fancy pants, groovy pea coats, long hair, and scarves – and they could not play rock and roll or blues. They were folk musicians who had picked up electric instruments and were doing boinky-boinky electric folk music.

“Marty [Balin] wrote some great songs and was a great singer, and Grace [Slick] added some grit, and they turned into a pretty good band. But when I first got there, they were all suddenly in competition with the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, the Byrds, and Simon & Garfunkel. The record companies just came to San Francisco and hovered around. 14 record companies offered me a contract, and we got them into a bidding war for a year and then finally I closed my deal.”

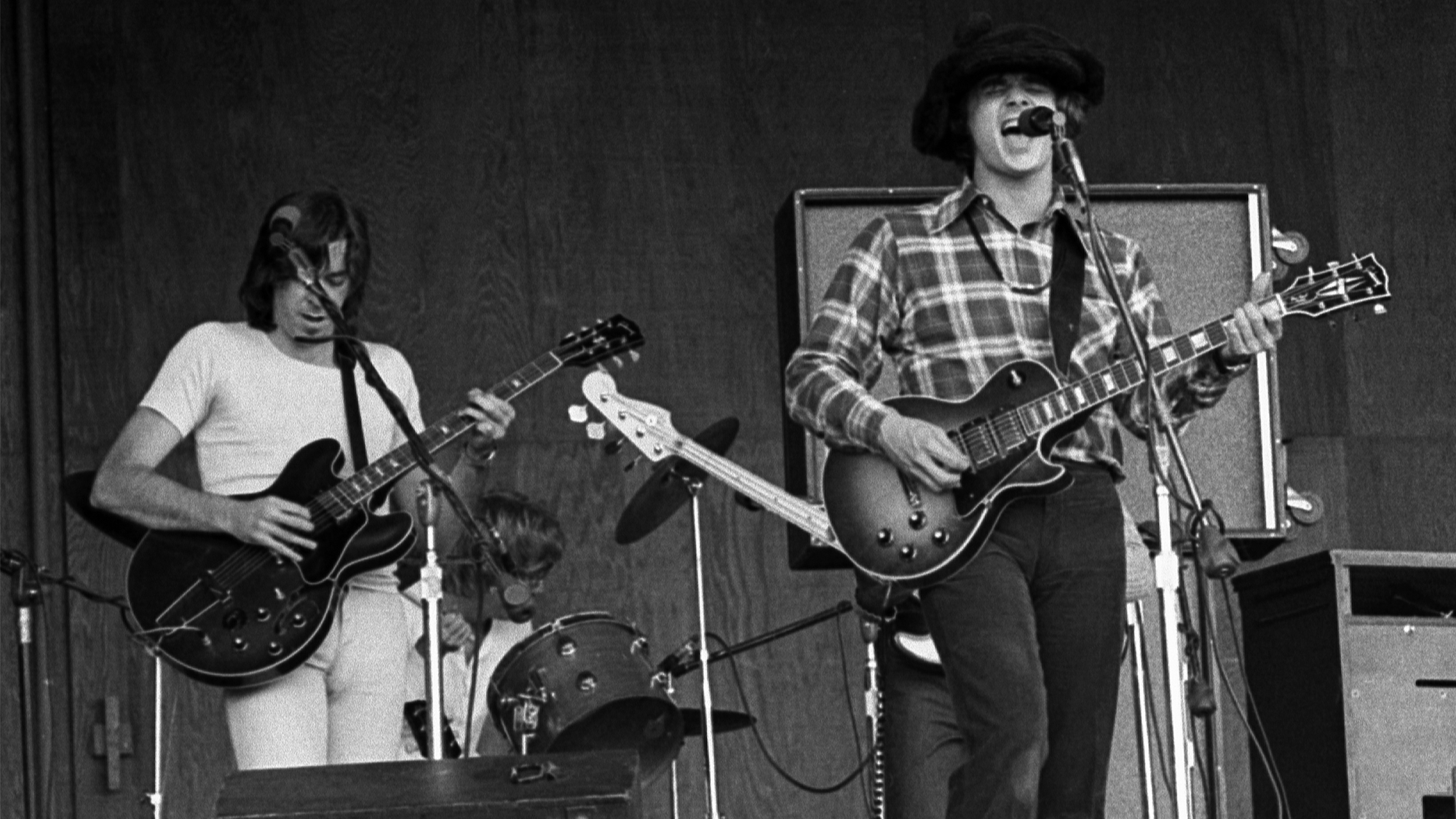

Boz Scaggs was in the band, and you started playing together at 12. At what point did it become clear to you guys that this was going to be your life?

“We started together in seventh grade, but I don’t think it became clear to us until college. We loved it, but we were so middle-class, going to prep school so we could get a good job. We weren’t going to be musicians, even though it wasn’t some little-kid band. We played Jimmy Reed, Bill Doggett, Muddy Waters. It was 1956 and we had a rock and roll band, and there were not a lot available.”

When the Beatles hit, every kid formed a band. You guys were far ahead of the curve.

“Yeah, we were 10 years earlier. When the Rolling Stones showed up, I thought, Huh? I’ve been playing Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland since I was 12. These guys are terrible! I was jealous that they got there doing Little Red Rooster. I grew up in that environment because of the culture in Texas. We had everything from Louisiana and Texas, plus Tex-Mex and country music. We had the Big D Jamboree on television every Saturday afternoon.

“When I got to Chicago in 1965 and saw Paul Butterfield, I went, ‘I can do that.’ He had just signed with Elektra Records, so it finally hit me that music could be a career.

“Boz and I had the most popular band at the University of Wisconsin, with [jazz pianist] Ben Sidran on keyboards. Then Boz went to Europe, smuggled hash across Russia, got busted in India, then made it back and became the Bob Dylan of Stockholm. When I got my deal, I asked him to come to San Francisco. We did two albums together but didn’t see eye to eye on the music we wanted to do, so I suggested he start his own band, which he did.”

You were exposed to incredible music as a kid. Les Paul was your godfather, and all kinds of jazz and blues musicians came through.

“Yeah. I loved it. My dad had a Magnecorder, the most expensive, unbelievable, technically advanced recording device that existed. He recorded Les Paul and Mary Ford – who got married at our house – and T-Bone Walker and many others on his Magnecorder. And he built the coolest stereo system you ever saw, all Formica, with big speakers. He was just ahead of everybody.”

How did it go over having T-Bone Walker at your house in Dallas?

“Not well! The neighbors liked my dad at first, and then they thought he was a communist. In 1950, they were calling Dwight Eisenhower a communist in Texas. My dad also had Black women working in his pathology lab, two of whom became pathologists themselves. When they had a Christmas party, they were arrested for having a ‘race party,’ with Black and white people together. They were handcuffed, photographed, and their pictures were put on the front page of The Dallas Morning News.

“We moved to Dallas when I was in second grade and I went to Stonewall Jackson Elementary School, where I was called a Yankee. I had no idea what that meant, but a kid jabbed me in the ass with a pencil the first day. I left when I was 16, went to the University of Wisconsin and joined the campus radicals. It felt good.”

Did your two brothers play?

“I taught my older brother to play bass for our band, and he was pretty good. My younger brother was a monster combination of Jeff Beck and Jimi Hendrix, but he was arrogant and snotty. He was very dangerous and he died at the age of 50. He was really something, but the kid couldn’t show up on time to save his life.

“I took acid in college in 1963, and my first trip was completely laid out. I had jazz, Motown, blues, poetry, art... I was taking a guided trip with a doctor of philosophy. When that was over, I went, ‘That’s it. I’m a musician. I’m not going to teach creative writing at this university.’ It just was obvious to me what I was going to do.

“I’d never seen my parents in college, but somebody they knew got married in Chicago and they came up to Madison and asked what I was going to do. I said, ‘I want to go to Chicago and play blues,’ which is what every parent wants to hear. My father heard, ‘I want to go work in a nightclub with gangsters and drug dealers and hookers. It’ll be great!’ My old man would have hit me with a two-by-four if he had one, but my mother said, ‘That’s a great idea. Here’s 100 bucks. You’re really young, you don’t have any responsibilities now.’”

But your dad was such a music lover! Did he come around to it? Was he happy when you made it?

“It was rough. He loved music, but not for his own kid as a career. My father was an alcoholic and a cynic. He was always sarcastic about it, like, ‘You only know three chords. I can’t believe this works.’ But at the same time, I’d be coming to town to play a big gig and would get a phone call from a secretary saying, ‘Your dad wants to see you on the way in and we’ve got a guest list. We’d like some tickets and T-shirts for them.’ And the guest list would be 350 people! [laughs] ‘$42,000 worth of tickets, Dad? Really?’”

“He was just like, ‘Hey, my son is famous! Come here and tap dance, rock star!’ It was creepy, and it took me a long time to learn how to deal with that. My brothers and my dad were alcoholics, and I drank till I was about 30. On my last little binge, I took a fire extinguisher and hosed down my agent, who was a guest at my house. Then I thought, ‘Okay, I’m through drinking.’ And I just absolutely stopped.”

You didn’t go through the program or anything?

“No, I wasn’t that kind of drinker, but my brothers and father were. They had

a really hard time with my success, and I was the middle kid trying to make everything cool. I brought Fly Like an Eagle home and played it for them, and my brother said, ‘That’s a bunch of shit.’ After years of that, I finally went, ‘We’re through now. I’ve given you all the money I’m gonna give you, I’ve put your kids through school. Mom’s dead. You’re on your own.’”

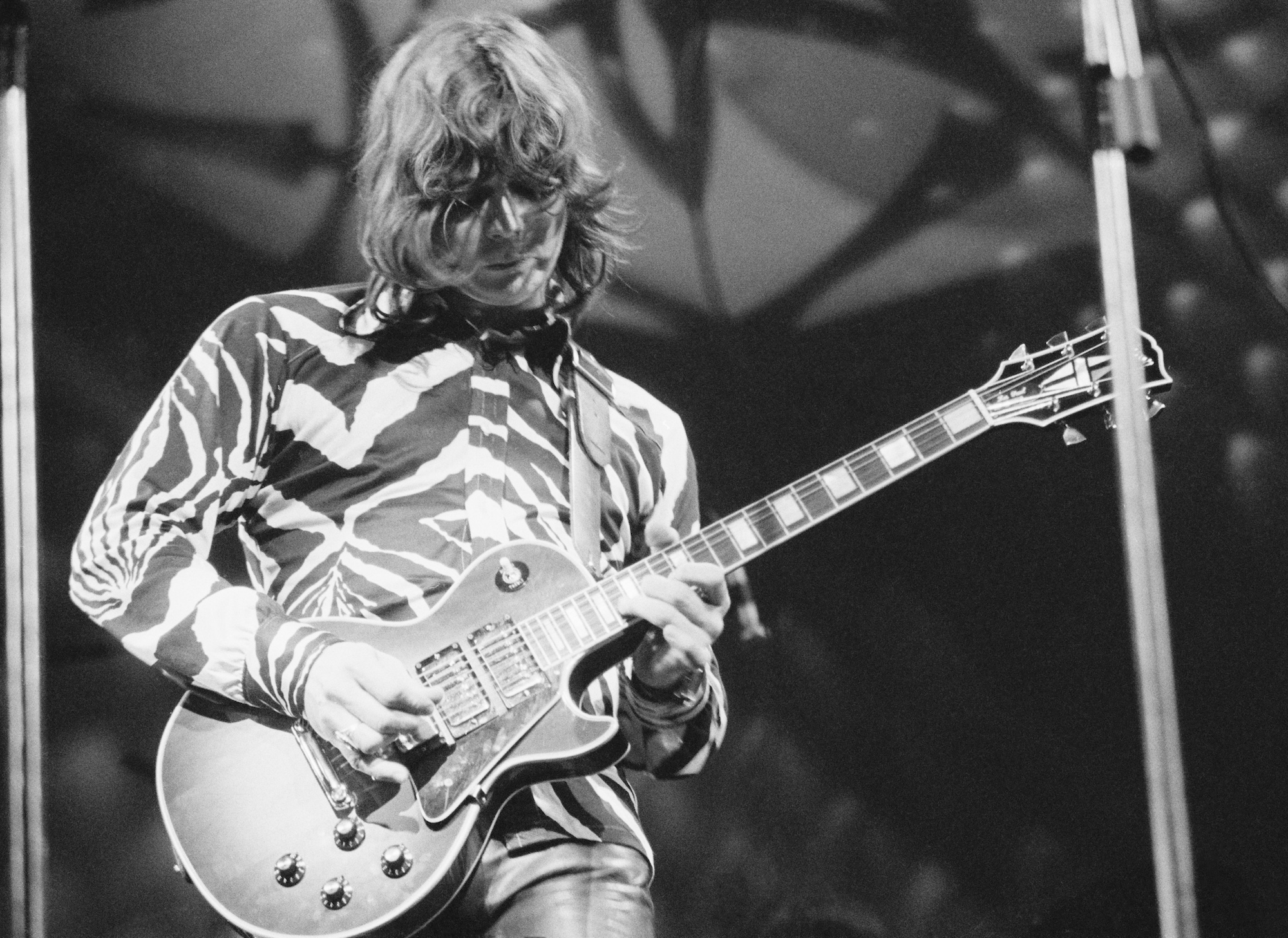

Does it still thrill you to perform your classic songs like The Joker and Take the Money and Run?

“Absolutely. It takes me three hours to get ready to do a performance. I do 30 minutes of vocalese while on a treadmill, walking four miles an hour at four degrees. It’s vocalese for Broadway performers, designed for people who are dancing and singing together. Then I take these little weights and get good and loose. Then I sit and play my guitar for 45 minutes to make all the fingers work – scales, songs, lead, chords, country licks... all of it.

“Then the band comes in and we do 30 minutes of group vocalese. I do all this because, when I open my mouth, I want any song to sound as good as you’ve ever heard it. I want it to be great – and it is. I love it. I’m so happy to be doing what I’m doing. I love playing and I love the challenge of keeping it very good.”

What are the three new projects you said you’re working on?

“I have solo acoustic sides. I am working through a lot of great material I’ve recorded with the Jazz at Lincoln Center guys over seven years of doing shows there. And I went into the studio in August with the band and cut a bunch of new stuff. The record business doesn’t matter – nobody buys any records, you don’t make any money, everything gets stolen from you, and there’s no accountability for it. It’s just up to us if we want to really make new music – and we do!”

Just because it’s what you do?

“Yeah. It’s an art form. It requires a certain kind of work and judgment and use of skills and tools. You don’t want them to get rusty. And I always loved making records and singles. Making hit singles is a great puzzle. That’s a real cool thing to do.”

- J50: The Evolution of the Joker is available now.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Alan Paul is the author of three books, Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan, One Way Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as Managing Editor from 1991-96. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort.

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue

"Get off the stage!" The time Carlos Santana picked a fight with Kiss bassist Gene Simmons and caused one of the guitar world's strangest feuds