Sixties Session King Vic Flick Reflects on Scoring Bond, His Most Famous Gigs, and Reminds Us To “Make Every Note Music“

As the guitarist behind the James Bond theme, Flick has left an indelible mark on pop culture. But he's also had brushes with Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton, and the Beatles, to name a few.

Any history of the British Invasion would be incomplete without recognition of Vic Flick, a guitarist whose name has as much sizzle as his playing. Flick made a splash on the London scene with the Bob Cort Skiffle, drawing the attention of arranger/composer John Barry, who hired him in 1958.

By 1960, the John Barry Seven had amassed fans via Juke Box Jury, and Flick’s 1961 composition “Zapata” was a hit for the septet. While arranging 1962’s “The James Bond Theme” for Dr. No, the first film in the spy-thriller series, Barry incorporated a motif utilizing the raw wallop of Flick’s Clifford Essex Paragon. With one electrifying riff, a decade came alive.

Flick was a prolific session guitarist, working alongside Jimmy Page, Big Jim Sullivan, and Eric Clapton, with whom he recorded the unused (and since lost) theme to the 1989 Bond film License to Kill. Sir George Martin frequently enlisted him as well – that’s Flick’s Fender Strat underscoring the instrumental “Ringo’s Theme (This Boy)” in A Hard Day’s Night – and his 12-string accents can be heard on Peter and Gordon’s “A World Without Love.”

For that matter, Flick made himself indispensable on recordings for Tom Jones, Cliff Richard, Dusty Springfield, Shirley Bassey, Petula Clark, and Herman’s Hermits, to name a few.

His 2014 memoir, Vic Flick, Guitarman: From James Bond to the Beatles and Beyond, chronicles a career that merited the National Guitar Museum’s 2013 Lifetime Achievement Award. The honor cites Flick’s “contribution to the history of the guitar,” aspects of which he reflected upon recently when he took time to chat with Guitar Player about his years in the business.

How did you start playing guitar?

My father taught music. I played piano at seven. After attending a dance, my dad got upset because the band was bad, so he decided to form his own. He played piano, neighbors played saxophone and drums, and my brother played bass. That left me nothing to play until a neighbor provided a Gibson Kalamazoo, a small-bodied acoustic guitar. I practiced until my fingers bled.

I developed listening to Tal Farlow, Les Paul, Freddie Green, and Charlie Christian. Being able to read music opened doors, but back then you couldn’t hear the guitar, so I found a tank commander’s throat mike and strapped it on the guitar’s machine head. I played it through the big speaker of my father’s radio.

Later, I met a bassist who introduced me to Bob Cort and his skiffle group. His guitarist was leaving, and I passed the audition with flying colors. That’s how I entered the guitar-playing world.

Connery only came to the studio once. He seemed very quiet and sat in the corner of the control room. I never got to know him. I once had a few beers with Timothy Dalton

What led to you joining John Barry?

Bob Cort’s Skiffle shared the bill on Paul Anka’s first European tour, and the JB7 accompanied Anka. That’s how I met John Barry. He could see I could play. Six months later, he asked me to join.

How did you come to play on “The James Bond Theme”?

Peter Hunt, the Bond films’ music editor, told the producers that Monty Norman’s original theme didn’t represent the film.

Peter had seen a 1960 Adam Faith film, Beat Girl, whose music J.B. composed and performed, and which heavily featured my guitar. Based on that, Peter recommended J.B. The piece of music we recorded, which J.B. arranged, was something Norman had first recorded in Jamaica, and it featured bongos.

It didn’t have a whack to it. He dug it from his piano stool. J.B. played it for me and asked, “What do you think?” I said, “Take it down an octave. Make it grungy like Beat Girl. Get that sound going.” That and the brass punched the Bond films to success.

What guitar and amplifier did you use?

Some hooligans stole my Strat after a gig in North London. At the time of the Bond recording, the only other guitar I had was the Clifford Essex Paragon, a cello f-hole acoustic. This guitar was manufactured in London. Diz Disley, a wonderful guitarist, was experiencing hard times in 1961 and sold it to me. I used that to record the theme.

The recorded sound was due to the plectrum I used and the guitar’s strings. I placed the DeArmond pickup near the bridge. I put a crushed cigarette packet underneath it to get it nearer the strings. That helped to get that round sound. Most important, sound wise, was the Vox AC15 amplifier. I used it on tour. It wouldn’t let me down – until it fell eight feet into a music pit and disintegrated.

Also important was the way the guitar was recorded. It was picked up by the mics for the orchestra, and it gave the guitar a mysterious, powerful sound. It was a sound we created, to a certain extent, and it had a bite that they loved. It was all go, go, go from then on. The first few Bond films were recorded at Cine-Tele Sound Studios [commonly known as CTS Studios].

Did Dr. No’s success surprise you?

Yes. The producers were on their last penny and didn’t know whether they’d be able to pay the band. At first, cinemas weren’t taking it. Suddenly word spread, and bingo! It took off like a rocket. It was a chance for J.B. to show what he could do with film music.

What were your subsequent James Bond films?

I did about six, with a couple of different composers. They kind of went orchestral; they didn’t feature guitar so much. I used about three Strats, a Gibson Les Paul, and an L-7C, which later a good engineer electrified for me.

Did you play on Shirley Bassey’s Goldfinger theme?

Yes. There was a funny moment when J.B. told her, “That last note isn’t long enough. You’ve got to keep going on it.” So Shirley slipped behind a studio partition, took her bra off and threw it over the top of the partition. She said, “Okay, let’s take this last note again.”

Describe John Barry’s style.

Thinly orchestral. He’d have a melody played on one instrument, then two or three others would come in. Now there’s so much film music with nothing to do with what’s onscreen.

Did you ever meet Sean Connery?

Connery only came to the studio once. He seemed very quiet and sat in the corner of the control room. I never got to know him. I once had a few beers with Timothy Dalton [who played 007 from 1987 to 1989]. In 1989, I did License to Kill with him, a film in which the music wasn’t used.

Was that your elusive recording with Eric Clapton?

Yes. A guy called me from the studios in South London to do a couple of hours work on the title. When I arrived, there were a few guys with suits. I said, “What the hell is all this about?” There was also Eric Clapton and conductor/composer Michael Kamen. We video-recorded it twice in an apartment on the River Thames.

It had quite an impact, with drums, bass, percussionists, Clapton, and me. It was a good, basic guitar thing. The two cassettes have disappeared. That would be like finding the Holy Grail

It had quite an impact, with drums, bass, percussionists, Clapton, and me. It was a good, basic guitar thing. After we finished, one of the suits said, “We’d like to sign you up to be a featured soloist.” Off they went back to America with their briefcases. I waited and waited.

I eventually phoned: “What’s happening about my being a star?” Kamen said, “Sorry Vic. That’s all off. You’re not going to believe this. Gladys Knight and the Pips are doing it.” Nobody else has heard our recording. It’s something everybody’s been searching for. The two cassettes have disappeared. That would be like finding the Holy Grail.

Does Peter and Gordon’s “A World Without Love” feature your 12-string?

I had a 12-string acoustic and a 12-string electric – the Vox 12-string guitar that they put on the market, which I hated. I used that on “A World Without Love.” There was a phase when the 12-string guitar appeared on everything. It became tiresome if you played the 12-string guitar six hours daily.

What was your relationship with the late George Martin?

I knew Sir George when he was working at Abbey Road EMI. He had a bit of an attitude, a bit of, “I say, old chap, come on.” He’d ask the fixers, or contractors, to line up session musicians. We got on well together except once. I heard George being interviewed on the radio.

There was controversy about session musicians doing the music part for successful groups like Peter and Gordon. George said, “Yes, and there’s some other trouble with session musicians. They don’t think. They’ll do something if you tell them. If not, they’ll just play what’s written. Sometimes they’re just more trouble than they’re worth.”

The Musicians’ Union allowed musicians to record four tracks without a singer, and as many titles as 20 minutes would allow with a singer. At the end, you don’t really know what you’ve done

I couldn’t believe it! It wasn’t true at all. Other session guys also disliked it. Nothing was done about the matter until I got a call from a fixer to work on a recording with George. Prior to the session, the other musicians and I agreed to just play exactly what was written, without adding any bits.

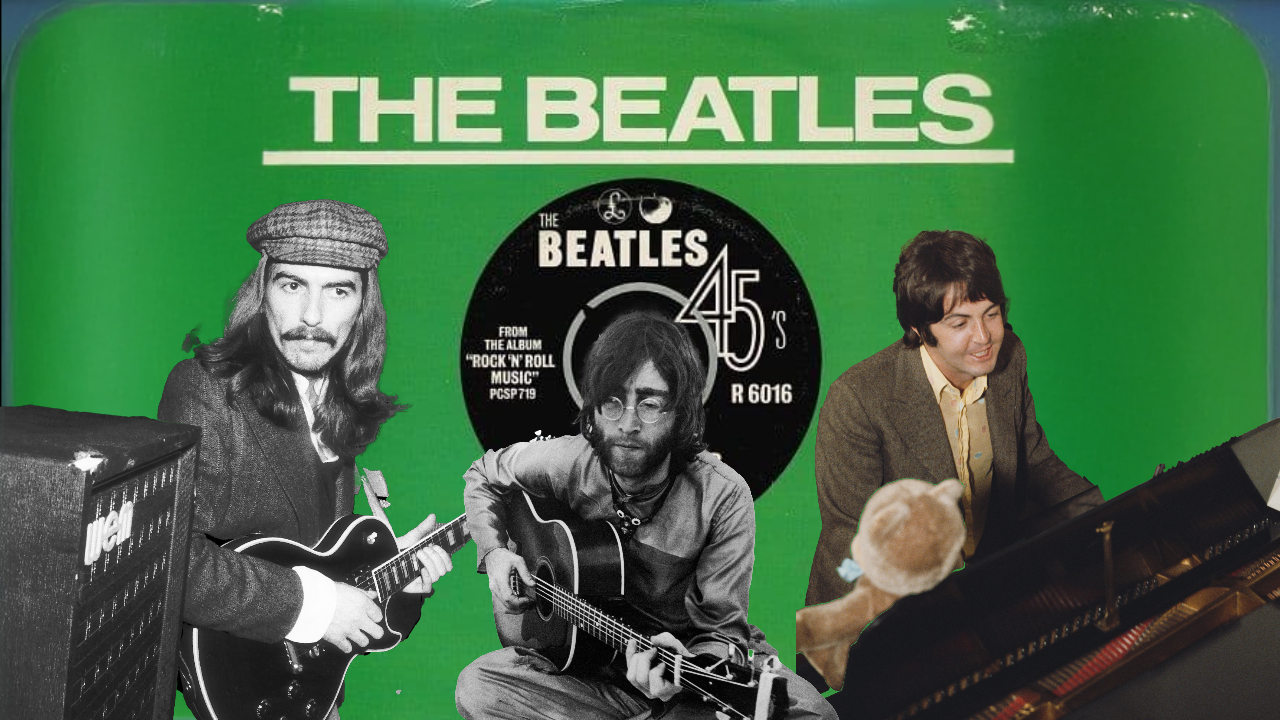

George put the music in front of us with the usual layered guitar parts and said, “Okay, let’s do it: two, three, four…” So we played exactly what was in front of us. Finally, George said, “Okay, stop. I shouldn’t have said that. I apologize.” It was a little slap on his hand. He was the last producer to audition the Beatles, and he signed them to Parlophone. He was a good producer, and he sorted them out.

At EMI, there was a coffee room. Sometimes we’d say, “Hi” or “How are you doing?” to one another – stuff like that.

Mostly, the Beatles kept apart, sitting at the table in the corner, unlike the session guys who would come in and spread themselves all over the place. I did some special pieces, like [the instrumental] “This Boy” theme in A Hard Day’s Night, where I play my Fender Strat when Ringo is walking along the river. And I play elsewhere in that film too.

Were you on other Beatles recordings?

When they were first recording, there were some unidentifiable sessions I was on with George Martin that were more like backing tracks than actual recordings. I can’t remember more than that, as it was the Beatles’ early days. The Musicians’ Union allowed musicians to record four tracks without a singer, and as many titles as 20 minutes would allow with a singer.

At the end, you don’t really know what you’ve done. You follow instructions, make stuff up, and play solos. It’s like film work with just audio cues. You turn over another page, without the film’s name on the music. That was like a factory job, but very good.

I was on all of Tom Jones' first hits. I probably used a Strat. I usually used a Strat, except on the Bond theme

What was your involvement with McCartney’s album Thrillington? [Released in 1977, Thrillington was an instrumental version of McCartney’s 1971 Ram solo album.]

I don’t think it was very successful. There were a couple of sessions, one with an orchestra and one with a small group. I joined about five other musicians. We laid about nine tracks. Then Paul had people lay on tracks. Paul didn’t come to the studio. He was in the control room. We went there to listen to some titles. He’s a nice guy.

On the other side of the British pop divide, you worked with Cliff Richard?

I knew Cliff before I recorded with him, when we were both performing at Butlins Holiday Camp in Clacton. He had a little band in the Rock and Calypso Ballroom. He would sit alongside the swimming pool with a guitar, and all the girls would be “oohing” and “aahing.”

You’ve also performed with Engelbert Humperdinck.

He was on a tour with the JB7 as Jerry Dorsey. His manager said, “We’re going to make a star out of you. We’ll give you a name and off you’ll go.” So they called him Engelbert Humperdinck, and it was under that name that we re-recorded his first five hits.

Another legend you’ve accompanied is Tom Jones. Which guitar did you use on “It’s Not Unusual”?

I was on all of Tom’s first hits. I probably used a Strat. I usually used a Strat, except on the Bond theme. Maybe I should have stayed on the Clifford Essex. I also had a Martin D-28. A nice guitar. I sold that. I’ve sold most of my guitars by now.

You sold a Fender Stratocaster on Pawn Stars. Tell me about that.

The host was very impressed. I got quite a bit of money for it because of the people I accompanied on it, like Tom, Petula Clark, and Nancy Sinatra. I also sold at auction the Bond film guitar. It paid its way. Some people asked, “How can you sell guitars?” I said, “They’re tools.” You get attached to them, but that’s how it goes.

And what about Jimmy Page?

I worked with Jimmy. He’s a nice guy and a great guitarist. He was born around the corner from me in southwest London. Jimmy couldn’t read a note of music. I helped him several times with that. I did quite a few recordings with him. A lot of it happened in Decca [Studio] 2, in the basement.

That was the place where a classic exchange of words between a musician and a fixer took place. Jimmy and I were sitting next to each other with our guitars. This fixer said, “What’s this I hear about you joining a group?” Jim said, “Oh, yes, we’ve got a tour coming up.” He said, “Well, what about these sessions?” Jim said, “I don’t know. I’ll do them if I can.” “Oh,” the fixer said, “you’re going to live to regret this.”

Now, of course, Jimmy is sitting in a castle in Scotland worth about 68 million, or something. We usually got paid with money in a little brown envelope. I once asked him, “What are you doing? Putting your money in the bank?” He said, “No. I’m gonna put it under the mattress.”

Some people asked, 'How can you sell guitars?' I said, 'They’re tools.' You get attached to them, but that’s how it goes

What is your advice to aspiring guitarists?

Don’t forget to make every note music. Guitarist Jim Hall said, “I don’t know what’s happening to the guitar world. Some of these guys sound like there’s a lot of notes looking for a tune.” And may I share this to say goodbye to you? Once the Moody Blues were on a television show.

I was in the orchestra. Justin Hayward came up to me and said, “Can I shake your hand? If it weren’t for you, I wouldn’t be here now.” Afterward, one of the group said, “He saw you on television several times and said, ‘I’ve got to do what Vic’s doing.’” That was nice.

- Vic Flick, Guitarman is available now via BearManor Media.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

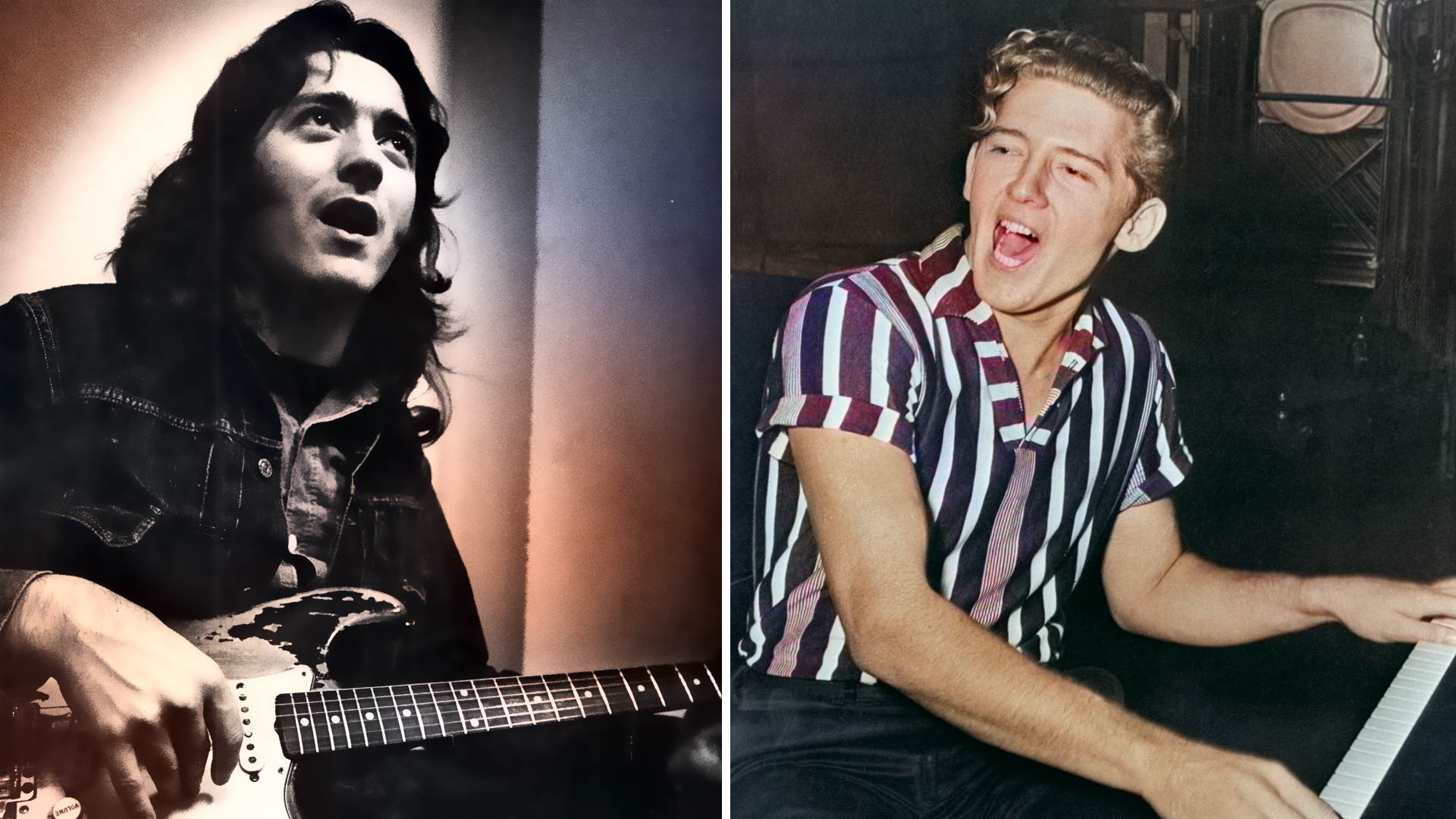

“He goes, ‘Play, boy,’ in that very southern way. I start taking my solo, sweating: ‘He’s going to hit me! I know it’s coming.’” How Jerry Lee Lewis terrorized Rory Gallagher, Dave Davies and Ritchie Blackmore

“I had just been turned on to Ravi Shankar, and I had an album in my suitcase. I gave it to George.” How David Crosby's casual recommendation changed George Harrison’s guitar playing forever