Samantha Fish Talks Her Role in the Blues

The electric guitar firebrand reveals how “blues always glued everything together” in this classic interview.

Samantha Fish climbs the steps of her 19th-century New Orleans home, shouldering her Arctic White Gibson SG as she retreats from the midday summer sun into a wide parlor. The air is thick with bayou humidity, but as a Kansas City native who spent her first 20-something years weathering winter blizzards, Fish doesn’t seem to mind.

As she finds a spot on her couch, the muted thud of drums sounds through the walls of a recording studio, situated next door in a former church. In New Orleans, music is everywhere.

“You could walk down any street and come up with an idea,” the acclaimed blues guitarist says. “There’s so much music around, and the people are inspiring.”

Fish grew up hearing bluegrass, Americana and hard rock, eventually finding her way to the blues through classic rock and roll. She taught herself the basics on guitar, then picked up licks from records and the jazz and blues guitar players she found in her hometown. She broke out of the Midwest blues scene with a power trio that showcased her fiery guitar playing and inimitable, howling vocals.

“I would pick up things here and there from other guitar players, just little theoretical bits,” Fish says. “A lot of what I do I learned by ear.”

Her early solo records – Runaway, Black Wind Howlin’ and Wild Heart – track her progression from traditional blues-rock to a rawer interpretation of hill country blues. Her slow-burning cover of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ “I Put a Spell on You” and faithful rendition of Black Sabbath’s “War Pigs” became highlights of her live sets and showed her musical range.

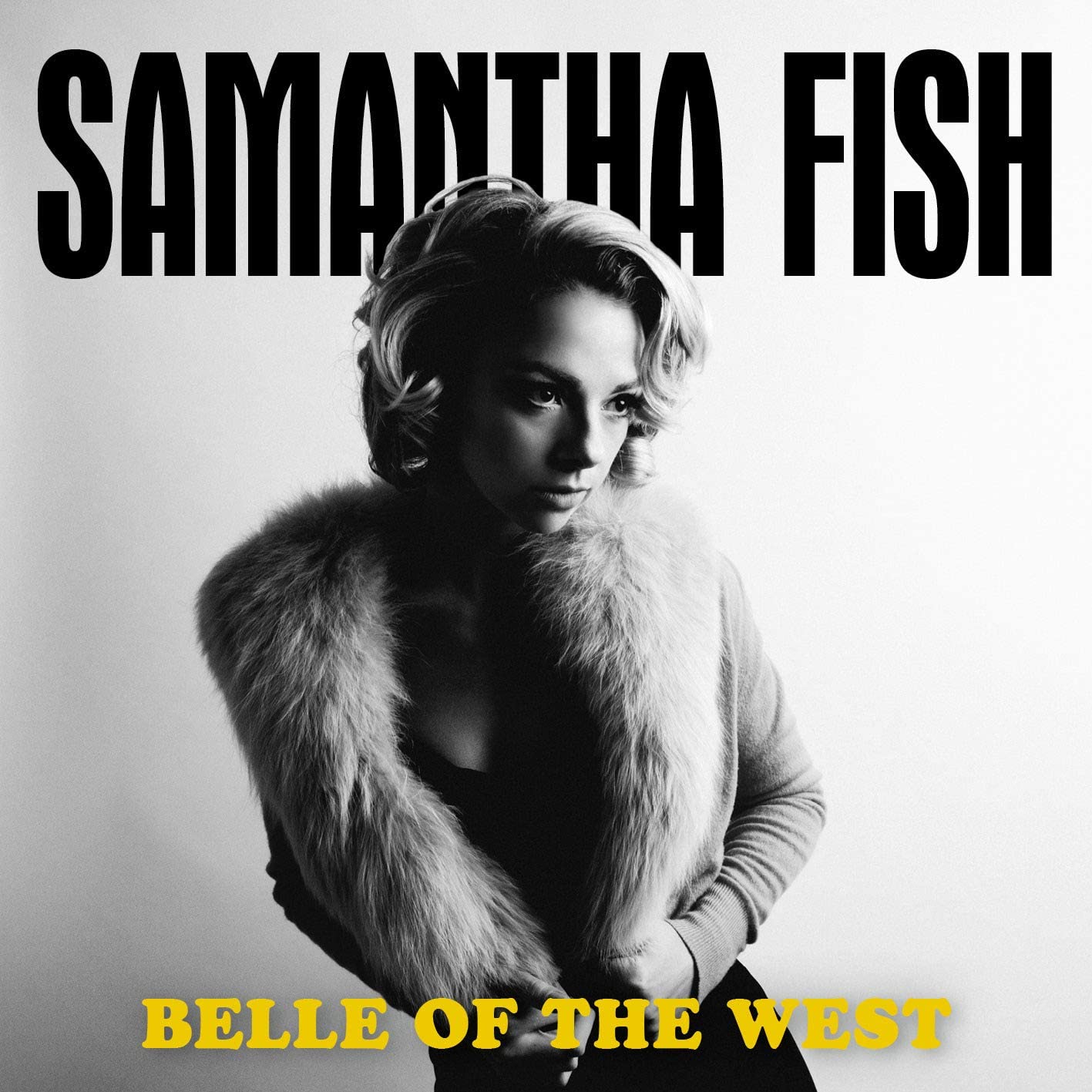

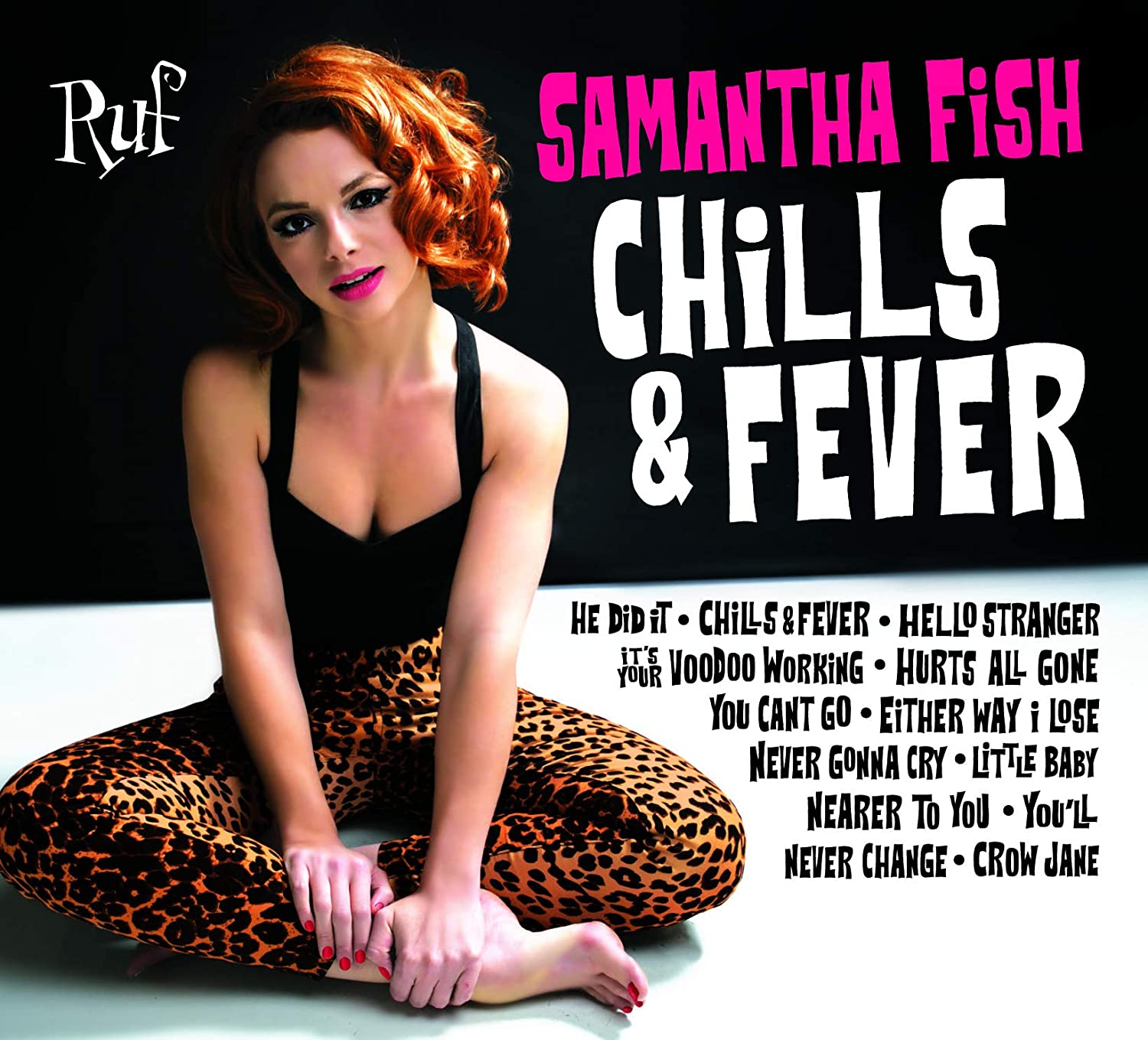

After absorbing the swampy Delta blues of the Mississippi, Fish followed the big river to the bottom of the basin, where it all flows together in a gumbo of sounds. Her later albums, Chills & Fever and Belle of the West, both released in 2017 on Ruf Records, expand on her recipe. The brassy and noirish Chills & Fever nods to classic soul and R&B; it was recorded with the Detroit Cobras and a horn section from New Orleans. Belle of the West digs deeper into Americana – with R.L. Burnside and Mississippi Fred McDowell influences – revealing her songwriting chops and ear for haunting melodies.

“What inspired me to start playing is sort of all over the map, and the blues always glued everything together for me,” she explains.

What attracted you to blues music?

I think it was just years of listening to guitar-oriented music and finding that a lot of it was based in blues. When I found Stevie Ray Vaughan and Jimi Hendrix – and even the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin – their love of blues music was so evident throughout everything they did, so I started just going backwards. It’s such a passionate, raw, emotive music, and it’s stayed relevant and evolved. It cuts to the heart of what most people feel and are going through. I just felt connected to it.

How did being in Kansas City shape your playing?

Kansas City has a long history of jazz and blues, and they had jams every day. That was why I started picking up standards: I had to bring songs that were oriented to the jams, songs that I could jump up and play and people could follow. I was going out every night of the week for a while there, at like 18, 19 years old, for years. I’d go to work or school and then get off and go play.

All of your albums have their own signature sounds. How have you grown as an artist throughout your releases?

I think the songs became a little more important than the solo. We’ve added more instrumentation. I grew up loving soul singers, which isn’t something I talked about much because I came up as a guitar shredder in a trio. [On Chills & Fever] I wanted to show everybody this other side, which is soul music. Then with Belle of the West, it was my love of Americana music and North Mississippi. There’s still a lot of guitar playing on it; there’s just a lot of layers.

Belle of the West opens with Shardé Thomas playing fife on “American Dream.” You can’t get more hill country than that.

That’s real stuff. She’s a direct descendant of [fife and drum player] Otha Turner. We had so much great talent on that record, and there were more females in the studio than ever. All these beautiful female voices – Lillie Mae sang on it and played fiddle, [upright bassist] Amy LaVere, Tikyra Jackson played drums. We had a choir of sirens.

Releasing two records in a year was a bold move.

We recorded Belle of the West really close after Wild Heart came out. We were just so fired up. There’s no overdubbing. You’re singing into this mic, you’re playing into this mic – you can’t really fix things. Then the concept for Chills & Fever came about, and it just seemed like the time to try that. They’re diverse records. I don’t think they would’ve worked if we put out two records that were blues-rock.

How did you hook up with the Detroit Cobras for Chills & Fever?

I’d made three albums that were trio-based, rockin’ guitar and stuff, and I wanted to spread out a little bit. I met Bobby Harlow, who produced the record, and he knew the Cobras pretty well. He and I had this idea for covering obscure soul classics – B sides that weren’t hits but should have been. We got this cool mix of classic Detroit R&B and soul, but also this rock and roll band backing it up. Then we brought in horns from New Orleans.

You expanded from a power trio to a seven-piece band in the process.

At first, I was afraid I was going to lose too much guitar, but there’s so much more to play to. It makes me be more creative, and we can take things further than we could before. When I hit the solo, it’s a little more surprising than when I was always playing all the time. A horn section can add such a great pad and lift and dynamic change that I couldn’t do as a trio all the time.

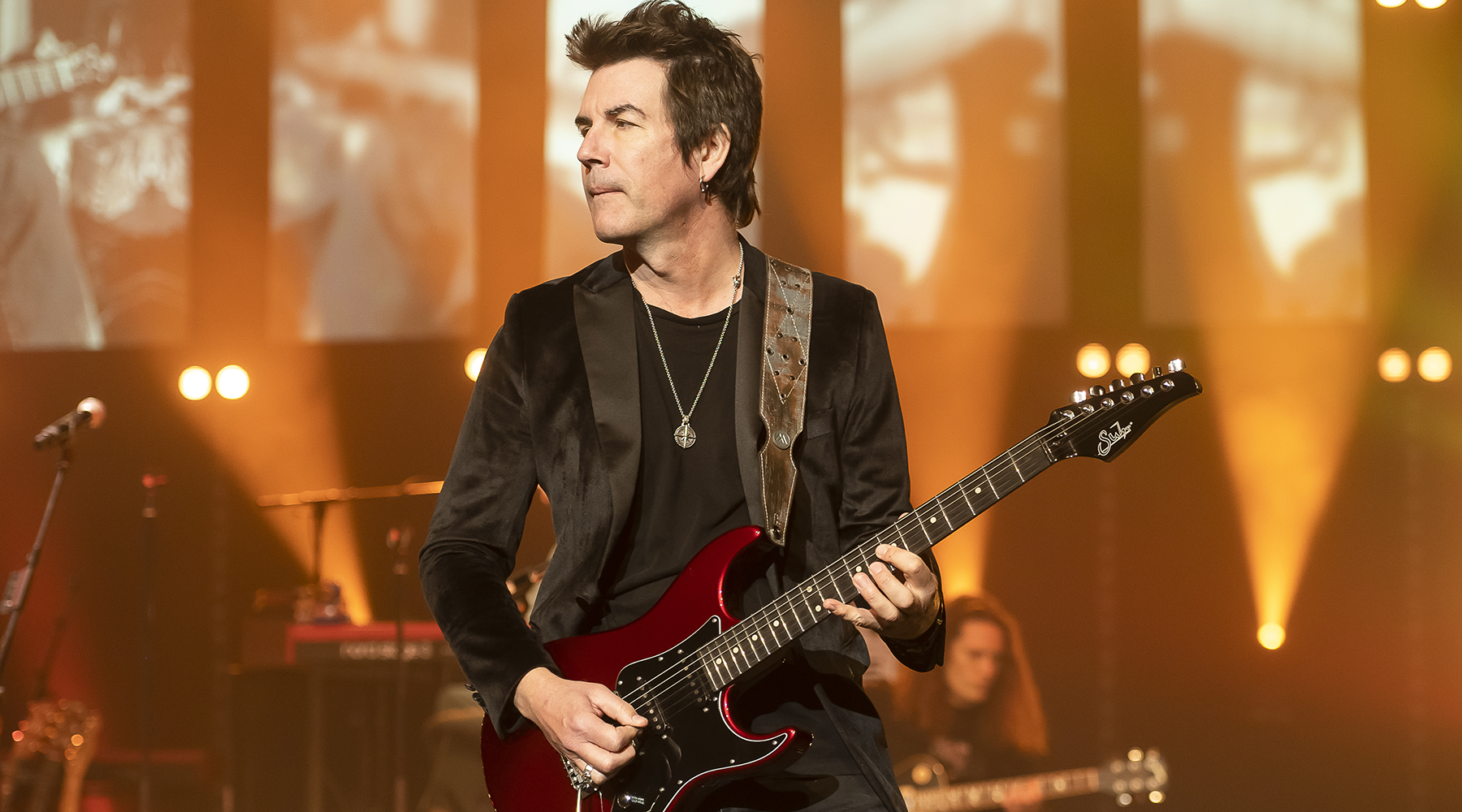

What gear are you using to bring out these styles live?

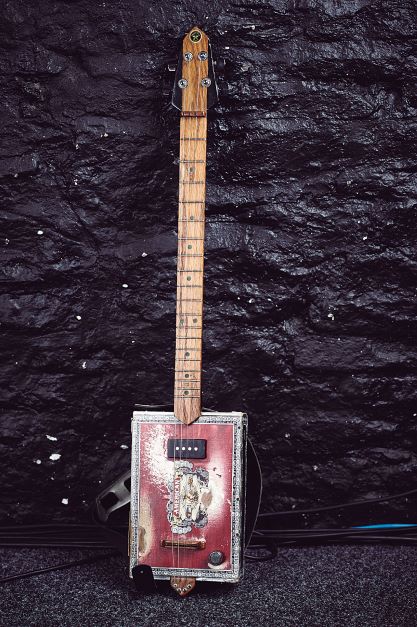

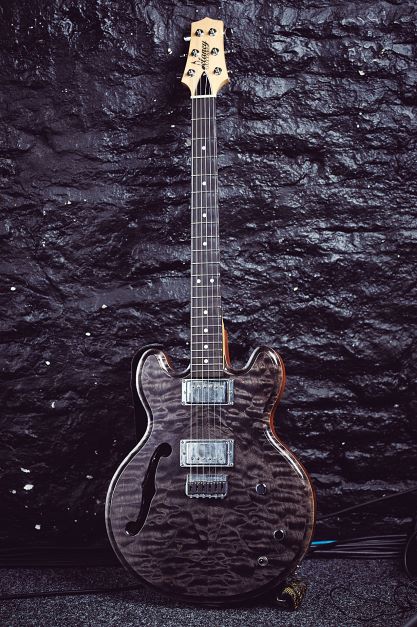

I’ve got an SG, and a Jaguar for light stuff like “Hello Stranger,” the Barbara Lewis song [on Chills & Fever]. I’ve got a Delaney 512 – you can get some funky feedback notes out of it. I have my Delaney signature model, the Fishcaster. I use that a lot for slide stuff. And cigar-box guitars, of course. I have one that’s called a Stogie Box Blues guitar, and it sounds mean as hell. And then my acoustic koa Taylor.

What role do pedals play in recreating such a wide array of tones?

I did away with pedals for years, but now I love using delay. You can work the knobs against each other, make crazy psychedelic noises, and you can slow the pitch down. One of my favorites is the [Analog Man] King of Tone. That’s my go-to if I have a big solo. It sounds so nice, like the tubes are warmed up to the perfect temperature and the amp is turned up to the right volume.

How do you view your role in the blues?

That’s tough, because I don’t know what my role is within blues music. I’m just trying to take what I love and internalize it, and maybe put out something that sounds a little different. I think that’s important, because you turn on new people to it that way. I love what the Black Keys did, and Jack White, because you could tell they were big fans of Delta blues. Young kids who maybe never would have heard a Junior Kimbrough record will maybe go out and buy one. So just take it and move forward with it, and always keep it as inspiration.

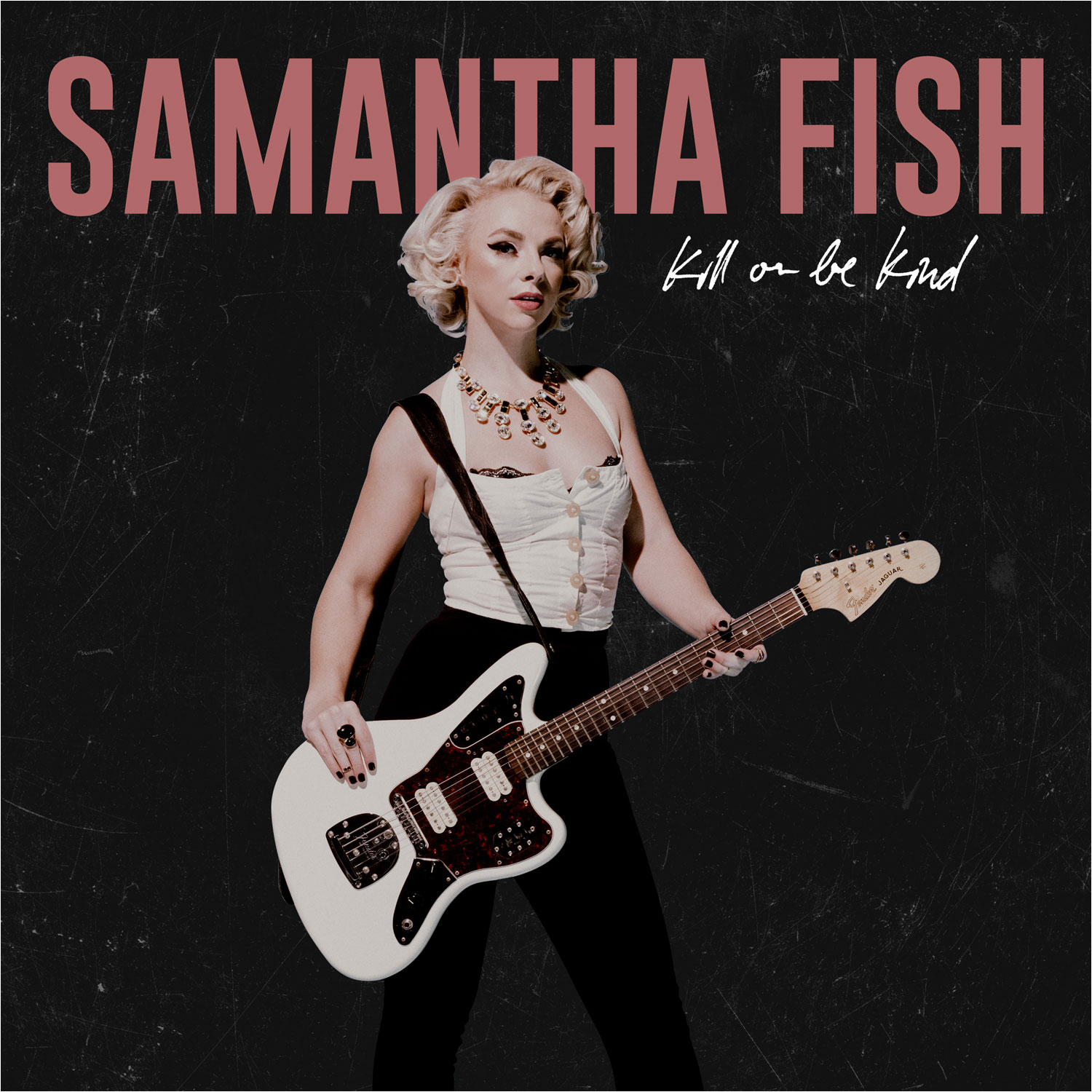

Look out for Samantha Fish’s new album Faster. In the meantime, why not grab a copy of her 2019 LP Kill or Be Killed here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jim Beaugez has written about music for Rolling Stone, Smithsonian, Guitar World, Guitar Player and many other publications. He created My Life in Five Riffs, a multimedia documentary series for Guitar Player that traces contemporary artists back to their sources of inspiration, and previously spent a decade in the musical instruments industry.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened