The Story of Robert Gordon and the Late Seventies Rockabilly Revival

Gordon's work with Link Wray, Chris Spedding, and Danny Gatton breathed new life into rockabilly. Here, he and his closest collaborators set the scene.

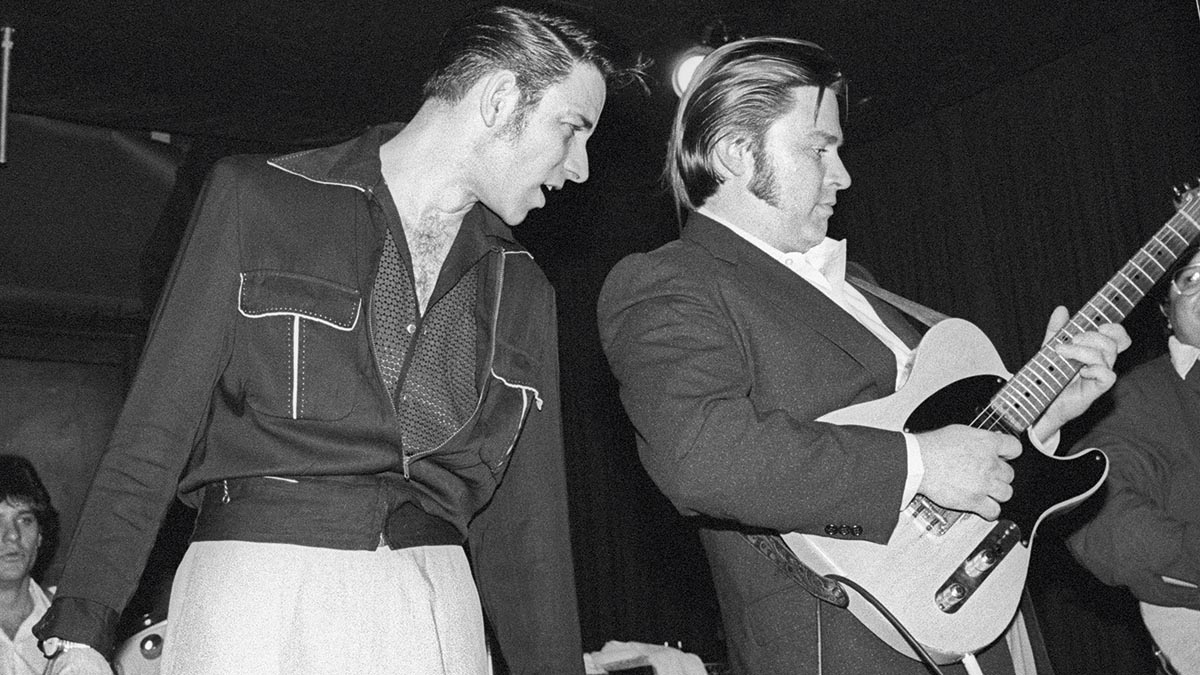

Robert Gordon is a man born out of time. Many fans and music historians believe that, had he been recording in the ’50s, he might have become a rockabilly legend. Instead, he kickstarted the worldwide rockabilly revival in 1977 with the release of his debut album, Robert Gordon With Link Wray, made in tandem with the guitar legend behind the 1958 instrumental hit “Rumble.”

Great things were expected for Gordon. His early albums were produced by Richard Gottehrer, the legendary producer and songwriter behind 1960s hits like “Hang On Sloopy,” “My Boyfriend’s Back,” and “I Want Candy,” as well as a major player in the ’70s and ’80s who helped launch the careers of Madonna, Blondie, the Ramones, and Talking Heads.

Gordon and Wray’s second album, 1978’s Fresh Fish Special, featured former Elvis Presley vocalists the Jordanaires and included a cover of Bruce Springsteen’s “Fire” that had the Boss himself on keyboards.

In 1981, Gordon had his biggest success with Are You Gonna Be the One, and scored a hit with “Someday, Someway,” a rockabilly tune written by Marshall Crenshaw, based on the 1957 Gene Vincent tune “Lotta Lovin’.” But then Gordon was sidelined by another rockabilly act, the Stray Cats, who became one of the biggest bands of the early ’80s.

“If I’d been coming through in the MTV age, I think I’d have become a big star,” Gordon tells Guitar Player. “Back then, people who didn’t even tour could become huge just because of MTV. I had a real strong image, and the music was unlike everything that was getting airplay.”

Gordon not only paved the way for rockabilly’s return to the mainstream – he also revived the career of Wray, who had been out of the spotlight for years since his ’50s instrumental hits. Wray made a number of rootsy, proto-Americana albums in the early ’70s but was mainly playing the oldies circuit when Gordon plucked him to be his guitarist.

Like John Mayall, the singer became an act through which many great guitarists passed. After Wray, Gordon went on to recruit Chris Spedding and Danny Gatton. More recently, he’s worked with players like Eddie Angel, Quentin Jones, and, most recently, Danny B. Harvey, who co-produced Gordon’s 2020 album, Rockabilly for Life, which has guest spots by Albert Lee, Steve Wariner, and Steve Cropper.

“The guitarists that I worked with never changed my approach to my music,” he said.

“I’ve always done my thing. I choose the songs, and I let the guitarists do their thing. I don’t step on their territory, but I like to hear what I like to hear, and it works out good. When you’re working with people like Chris Spedding and Danny Gatton, you don’t have to tell them too much. These guys have been there and done that, and they’re the best. I always let them do their thing before I open my mouth.”

Here, we let Gordon, and a number of key contributors to his work – including Spedding, Jones, Harvey, and Gottehrer – tell the tale of his nearly 50-year career in rockabilly.

Robert Gordon: Link Wray was a wonderful friend. He was 20 years older than me. I first saw him when I was nine years old at an amusement park in Glen Echo, Maryland. My father took me and my brother there, and they used to have shows on the weekends. He was doing “Rumble,” and it blew me away.

When I got the deal with Private Stock [Records], Richard Gottehrer asked me who I’d like to work with. We knocked it around for a couple of weeks and then he suggested Link, and I said that would be awesome. He got Link to come to New York, and we hit it off.

Richard Gottehrer: I met Robert while he was still singing for New York City punk band Tuff Darts. He said to me that he was thinking of leaving them and putting together a rockabilly band. He was really knowledgeable about the music. He really knew his stuff.

The first recordings that we did, I wish I still had them. Johnny Thunders played guitar and Marc Bell played drums. We did it at Plaza Sound Studios, where I did a lot of recording, including the first two Blondie albums. This wasn’t really a band that was going to hold together, because Marc wanted to do his own thing and became Marky Ramone, and Johnny was Johnny. [laughs] We knew we had to find another guitarist.

Gordon: Link wasn’t playing rock and roll as such when he joined up with me. I guess he’d been out of the limelight for a while. It had probably been 20 years since he’d had a hit record.

I’m very proud of the fact that I wanted to put his name on the album cover. It was billed as Robert Gordon with Link Wray. That was my decision, because I wanted him to get the recognition he deserved, and then he went on to have a second coming, I guess you could say.

Gottehrer: Link was doing the oldies circuit when we caught up with him, almost forgotten by the younger generation of record buyers at the time that we brought him onboard. He was very interested in much heavier, guitar-driven music, rather than straightforward rock and roll. We really connected on a personal level. He used to stay at my house when he was in town.

Gordon: Link was a great entertainer. He was terrific in the studio because he was controlled. [laughs] Live, it was a different matter, and it was difficult for me as a singer. Link knew just one way to play and that was with the volume on full. That was the kiss of death for me.

We did the two albums and two major tours, but then we parted ways, remaining friends. Link was a great guy to hang out with, and he was kind of a mentor to me, as that was my first real experience out on the road, even though I’d been in local bands before that.

Link was a very quick worker in the studio. He was a redneck, and his chords sounded like him. No one else plays chords like Link. He could play a slow, soulful ballad and play a ferocious solo that could still make you cry. He was amazing. Link’s main guitar on the records was a ’61 SG. He dropped that though and broke the damned neck.

He then went on tour with a ’66 Yamaha SG-2, which he called Screamin’ Red. He’d turn that all the way up and just beat the hell out of it. [laughs] For amps he was using an old tweed Fender Bassman, I think. He’d turn it way up loud. He had a lot of soul. It just got too loud for me in the end.

I think it did for a lot of people. I’m sure he lost a lot of hearing along the way, I know I did, and I have to wear hearing aids these days. This is what happens when you play rock and roll from 15 years old like we did. [laughs]

Gottehrer: The way that Link played, the way he attacked the instrument, the spirit that came out of it, I think these were the elements that made him so influential to so many rock guitarists. You never knew what you were going to get from Link.

I think there is a lot of stuff still in the can from those two albums with Link. I had multitrack tapes from all of those sessions that got stolen. I had a whole wall full of tapes with outtakes and everything man, and somebody ripped them off

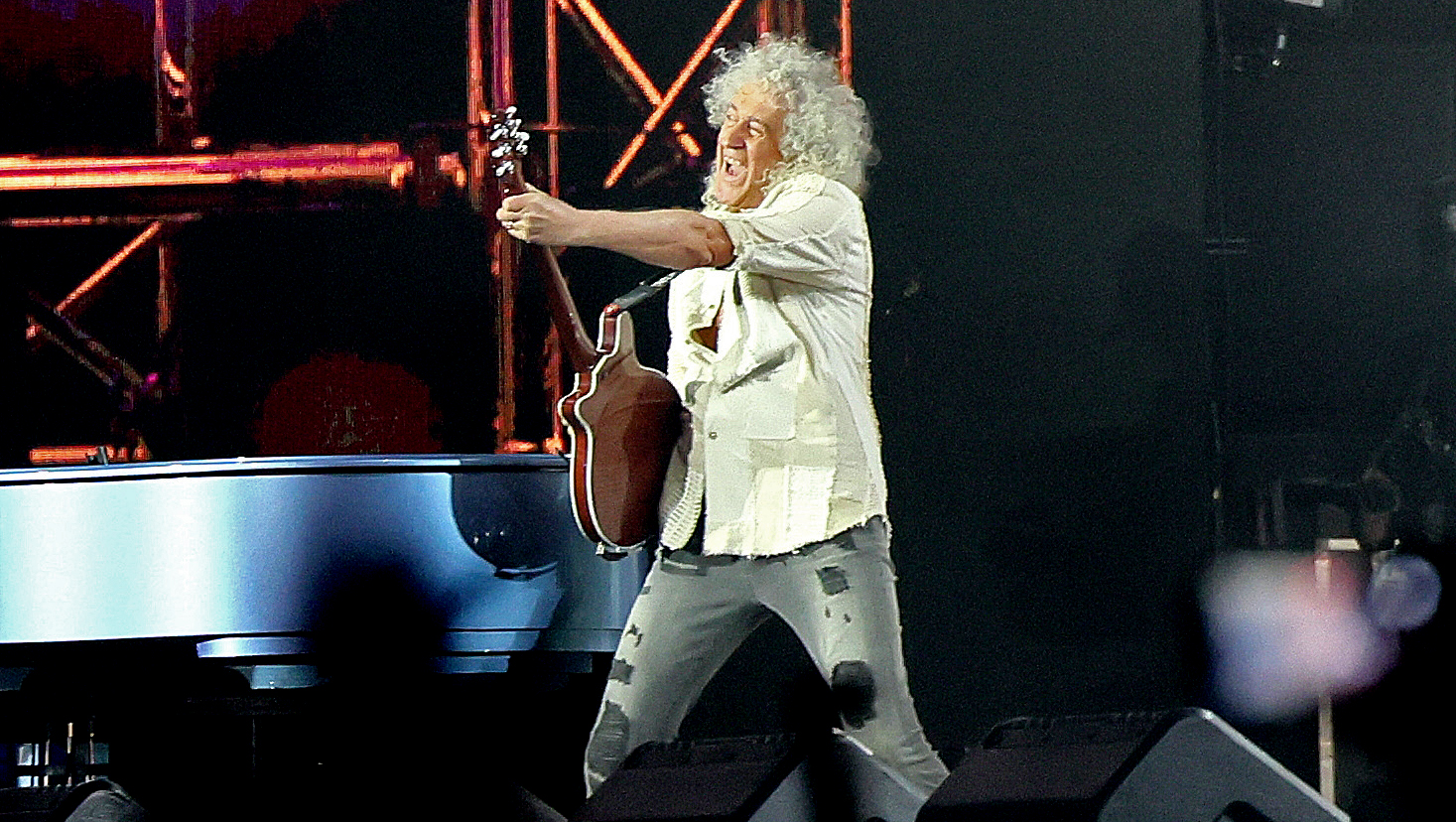

Robert Gordon

He’d play a solo, and it could be amazing, but if there was just one part that wasn’t right, he would never punch it in; he had to do the whole solo again, or else he just didn’t feel it. You had to capture him in the moment. He was very unpredictable. It is a crime that he isn’t in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Link understood the music perfectly, of course.

He felt the Elvis vibe that Robert had. Everybody respected him in the studio, and he was quite a fast worker. He could intuitively do what every song required without any discussion. We spent a few weeks on the albums at most, while other acts were taking months.

Gordon: I think there is a lot of stuff still in the can from those two albums with Link. I had multitrack tapes from all of those sessions that got stolen. I had a whole wall full of tapes with outtakes and everything man, and somebody ripped them off. There must be some copies somewhere.

It’s a real shame – there was so much good stuff on there. I’ve still got some reel-to-reel tapes that are good enough to use for one last play before they fall apart, I guess. Maybe someday someone might want to come in and try to do something with them.

It was totally mutual when we parted. Link wanted to do his own thing, and of course I was moving on too. I wanted to get into a more modern sound, and that was why I went with Chris Spedding next.

I loved Link, but he was really locked into a certain time, and although I’ve always done music from that period, I’ve mixed it with all kinds of things, including new music by new writers as well, and it got a little tired for me.

Gottehrer: Chris was primarily a studio musician when he joined Robert, whereas Link was primarily a live musician. So Chris brought a very different approach. They were both amazing guitar players. Link had a more organic quality; he could just spit solos out.

But Chris was more in control of what he was doing, I think. With Link, it was in his fingers, and perhaps with Chris it came from his head via his fingers. That is in no way meant to diminish his ability. He is a tremendous player. It’s just a different approach.

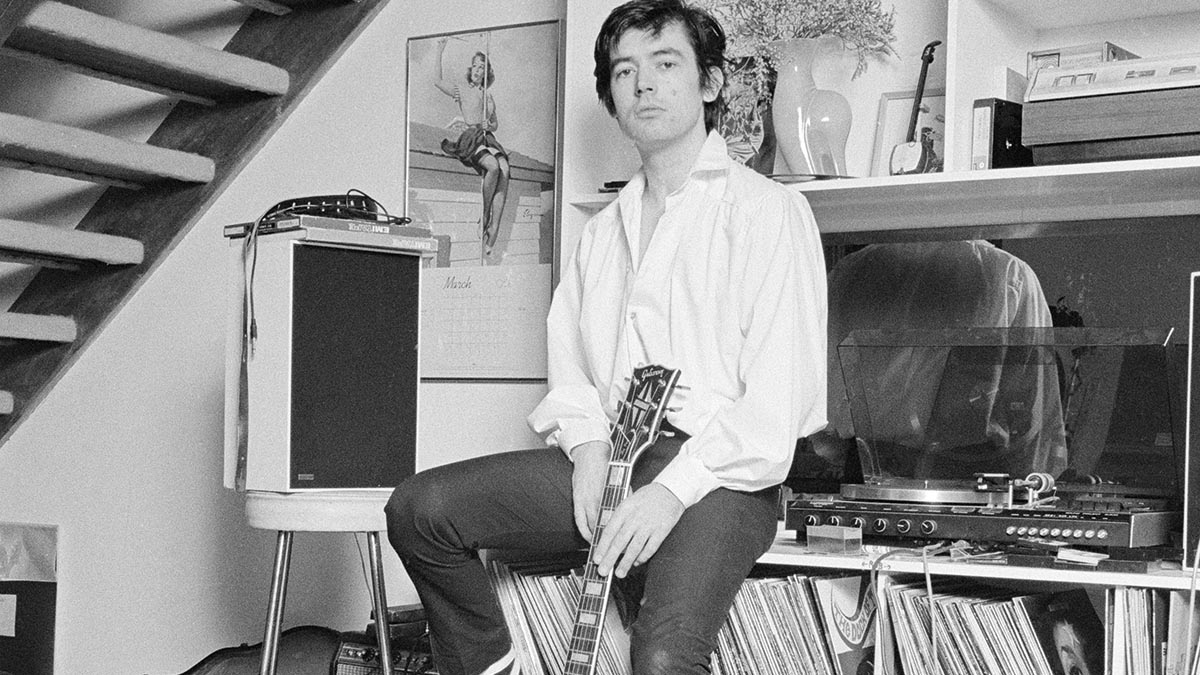

Chris Spedding: I got a call from Richard Gottehrer saying that Robert and Link were doing my song “Wild Wild Women” live, and he’d suggested maybe I’d like to get up onstage with them for that song. I thought that was a great idea, as I’d never thought of myself as a lead singer, and Robert had such a great voice that I thought it would be perfect if I could get him to sing a few more of my songs.

I then got another call from Richard saying Link and Robert were splitting up and did I want to play guitar with him. I thought that was even better in terms of getting my songs out there. I was still living in London at the time, and I’d just returned from touring in America with Bryan Ferry.

I really loved New York. I thought, I’m going to move to New York; I’ve got nothing to lose and I’ve got a gig. In the end though, he’s never, to this day, recorded any of my songs, not even “Wild Wild Women.” [laughs]

Gordon: Chris was still loud as shit but definitely more manageable than Link. We always use traditional monitors rather than in-the-ear monitoring, which exposes you to more volume. He originally came over to do the one album, Rock Billy Boogie, and stayed for 40 years. [laughs]

Spedding: Before hooking up with Robert, I was playing music that was, to my mind, very ’50s American influenced, but when I played it to Richard, he said it sounded really English. [laughs] I was aware of the first album that Robert recorded with Link, so I knew where he was coming from.

I didn’t slavishly try to reproduce ’50s rockabilly sounds; I would just leave a Memory Man on for slapback echo and never really adjust the tempo. I think my amp was a Fender Deluxe Reverb, and I played a Les Paul and a Gretsch 6120, but I’d changed the pickups for Gibsons so that I could sound more like Scotty Moore. I would often use my Flying V live, though.

Gordon: Me and Chris are still working together even now. He played on a track on my last album, Rockabilly for Life.

Spedding: I guess we’ve come to an understanding with each other after 40 years of playing together on and off. We never rehearse. He’ll email me and ask me to learn whatever song he might want to do. We’ll just run it once at the soundcheck.

Gordon: Chris went to the West Coast. We’d done three albums together for RCA. The next record, Are You Gonna Be the One, in ’81, was going to be a whole different kind of album. I worked with a different producer for the first time, Lance Quinn, who is also a great guitarist who played rhythm guitar on the album alongside Danny Gatton.

I knew of Danny, but I’d never worked with him. Lance brought Danny into the project because they’d worked together before, and we hit it off immediately. He was wonderful in the studio. Nobody plays that style of music better than Danny. He was the best. Having said that, I can’t really compare him to Chris or Link, as they are all totally unique.

Danny was a traditionalist, and Spedding was way more modern, which was something I really liked about Chris. He can play the roots music, but he brings his own style. Danny would do some tricks live, but I was never a fan of him playing slide with the beer bottle [one of Gatton’s favorite show-stopping tricks].

I could just have kicked that out the door. I didn’t like that. Danny was great in the studio, but live he overplayed. I know that impressed some people, but not me. I really loved Danny, but I didn’t like that at all. But he was a genius, absolutely.

He got that big record deal with Elektra after working with me, but he didn’t like the corporate world, which was why he went back to working with a small independent company again after he did those two albums for Elektra.

I wonder if he was a little depressed about how things went with them. They didn’t do as well as they should have. I think you really only get one shot in this business, and it’s a rough business. Danny never showed any sign of anything troubling him when we were together. That’s why it was such a shock to everyone, especially me, to hear that he’d taken his own life.

I mean, I was a bad boy in the ’80s, but Danny really was not. He’d drink a beer and that would be it, but the rest of us were doing drugs and everything else. Danny wanted nothing to do with me after our time together, so 10 years went down before I talked to him again.

I was a mess at the end of our touring and recording. I really needed to get off the road. Just months before he passed, we were discussing going back into the studio together again. I was really looking forward to that, but of course it wasn’t to be. I miss him very much. He was a wonderful guy, and he’s very well respected by musicians. For guitar players everywhere, Danny will always be a hero.

Quentin Jones: I was a huge fan of Robert’s work. Guys like Wray, Spedding, and Gatton were like gods to me. I never thought I’d end up playing with the man. I did two albums, Robert Gordon, in 1997, and I’m Coming Home, in 2014, which I co-produced with Robert.

I was a little inexperienced when I did the first record. He really cracked the whip on that album, and I credit him for helping me develop as a player. He would say, “These are the notes that I want you to play,” and he’d sing them for me. By the time of I’m Coming Home, things were different. Robert gave me a lot of freedom as a guitarist and a co-producer.

Gordon: My new album is Rockabilly for Life. We released it as a 30-track set. The record company wanted to feature a special guest on each song, so we recorded 15 tracks in a raw state, with Danny B. Harvey producing and playing guitar, and then the guests replaced his guitar with their parts.

I was not happy about having the guests on there at all, and I insisted that the original rough-mix tracks be part of the package, because I think they are so much better. The label chose who the guest artist would be; there’s a number of them on the record that I would have never put on there. You can just buy the album for the 15 Danny B. Harvey rough-mix tracks. It’s one of the best albums in my catalog.

Danny B. Harvey: There were some great guests on the record, but Robert paid me the huge compliment of saying that he preferred my playing on the original raw tracks, which was why they ended up issuing the album with all the tracks that I played on, as well as the versions with the guests on.

The brief was to get back to the raw sound of his earliest albums, which was fantastic for me, as they were so influential. Our goal was just to get that classic Robert Gordon feel. I pushed for him to sing in a higher key than he felt was natural for him, and he said he was really pleased with the results.

He said, “Man, that doesn’t sound like a 70 year-old on there!” [laughs] I think that is part of the reason why the record is redolent of the first records he cut.

Gordon: There was no rockabilly revival when I broke through. There were people here and there playing it, and it was always popular in the U.K. and Europe, but it tended to be older guys, whereas I was a lot younger and had a real strong image. The Stray Cats really benefitted from the MTV age, although I think I did kick off the rockabilly revival in the U.S.

Spedding: He really was one of the very first people to revive rockabilly, but he never really got the credit for that. I think the success of the Stray Cats a little later took the oxygen out of that. Their global success overshadowed what Robert had pioneered with Link, which is a shame.

Gordon: I think, back in the day, if I’d had another couple of albums with RCA, I could’ve been huge. They were debating picking up my option when my manager said, “To hell with them, we’ll go someplace else,” and like an asshole I listened. And that was the end of my major-label contracts.

I should have just stuck with RCA. I would’ve been there with them for MTV and had the benefit of their promotional push. I don’t think I’ve gotten the credit that I deserve for my role in the rock and roll story. I suspect I might one day.

- Rockabilly For Life is out now via Cleopatra.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.

"Get off the stage!" The time Carlos Santana picked a fight with Kiss bassist Gene Simmons and caused one of the guitar world's strangest feuds

“It’s a special kind of moment when you hit that first note of a solo and you literally get nothing.” He’s played with David Bowie and the Cure, but Reeves Gabrels says things don’t always go right, even for the pros