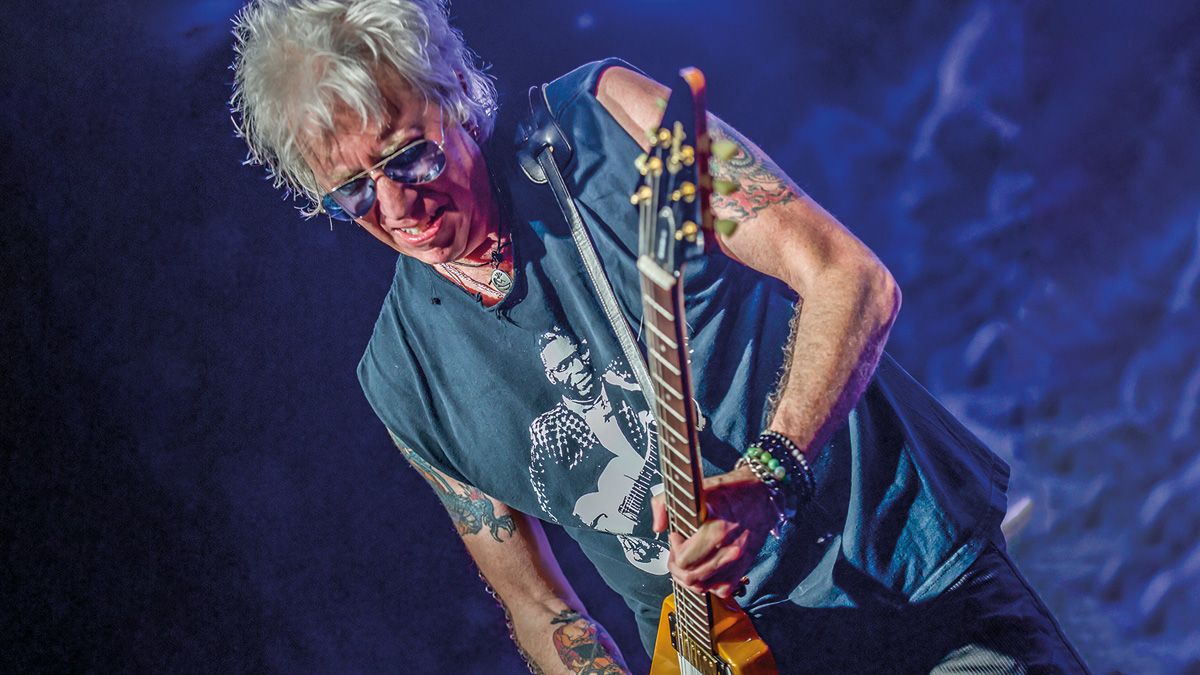

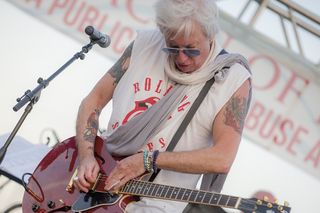

In addition to his two-decade run as a member of Joan Jett and the Blackhearts, Ricky Byrd has played guitar alongside a list of music legends that includes Bruce Springsteen, Elvis Costello, Ringo Starr, Alice Cooper, Ian Hunter, Smokey Robinson, and Mavis Staples.

When asked if he’s got a cool rock-and-roll story, he comes up with a beauty. “I was playing a benefit at Carnegie Hall with Roger Daltrey,” he begins. “At the soundcheck, I said, ‘Rog, you’re going to swing the mic, right?’ He said, ‘Do you think I should?’ And I go, ‘I’ve been waiting for this moment for 20 years, man. Swing that mic!’

“So we’re doing the show, and during ‘Behind Blue Eyes,’ we get to the middle section and I hear this whizzing sound. I turned and the mic missed my head by two inches. I saw Roger looking at me, and he’s got this big grin on his face.” He laughs. “I’ve got a million of those stories. I’m truly blessed, man.”

Byrd feels blessed for other, more significant reasons. Now celebrating his 33rd year of sobriety, the Rock and Roll Hall of Famer (he was inducted with Joan Jett and the Blackhearts in 2015) works as a drug and alcohol counselor, visiting schools and detox centers to perform and lead recovery music groups.

Since leaving the Blackhearts in 1991, he’s released a number of solo albums, including 2015’s Clean Getaway, on which he detailed his journey through sobriety.

I’m a product of all the music I listened to as a kid, and I’m not ashamed to nod to my influences. That could be anything from Sweet to the Stones and the Faces

His newest solo disc, Sobering Times (Kayos Records), continues that narrative. Joined by ace musicians such as Steve Holley, Liberty DeVitto, and Thommy Price, among others, Byrd punches hard on gutsy rockers like “Quittin’ Time (Again)” and “Together,” while he sprinkles some rugged Stones/Faces flavor throughout an inspired cover of Merle Haggard’s country classic “Tonight the Bottle Let Me Down.”

As for the album’s title, Byrd admits that it carries a dual meaning. “We were finishing it right when the pandemic hit,” he says. “I was on the phone with somebody, and I said, ‘These are sobering times.’ And then it hit me: That’s just perfect.

“The thing about recovery, if you’re lucky enough to find your way through, is that you realize you have no control over it, and if you don’t change, you’re gonna die. The title can definitely relate to what we’ve all been going through for the past year.”

The thing about recovery, if you’re lucky enough to find your way through, is that you realize you have no control over it, and if you don’t change, you’re gonna die

What makes you pick up the guitar these days? Is there some sort of new secret you’re still trying to unlock?

Of course. I’m amazed that I still go, “Wow. I’ve never played that freaking line before.” Each time I pick up a guitar, whether it’s acoustic or electric, it leads me in a different direction, especially when it comes to songwriting. When I was writing this record, I tuned to an open E for a couple of things, and that led me somewhere new.

But if I’m just playing, I can get into a meditative state. Or maybe I’ll put on some blues. I’ll play along to an Elmore James record, and I’ll just go into its world. That’s still the greatest feeling. Of course, I can get that same feeling from watching baseball for four hours. [laughs]

You’ve been solo for a while. Do you ever miss being in band?

Sometimes, sure. A few years ago, I put together a really cool blues band with [bassist] Amy Madden and [drummer] Bobby T. Torello. We played clubs in the city, just for fun. I had my Flying V and a little Fender amp. It was a blast and we kicked some ass.

I don’t miss the whole rigamarole of planning a tour. I don’t think I could go on the road now for months at a time. I’m just not that guy anymore. But yeah, being in a band was a big part of my life for years. When I was with Jett, we toured constantly. And if we weren’t on tour, we were recording new stuff. It was hard work. The older I get, the harder it is to be in that lifestyle.

But I’m lucky in that I get called to do cool events with big stars – well, before the pandemic. That kind of thing keeps me on my toes. But as far as having a regular band? Unless you have a giant, successful band, that’s expensive to keep afloat.

After you left the Blackhearts, were you nervous about making the transition from guitar-player guy to frontman?

No, because I’ve always been a singer. Even before the Blackhearts, I used to sing in bands. For me, when I went solo, it was more like, “Okay, who am I as an artist?” At the beginning, I put together these little bands in New York and everything sounded like bad Stones. I was like, “That’s not it yet.” So it took a while, but it was cool.

I got sober and I got myself a publishing deal. I was looking forward to being home while I wrote songs for Sony, and then I got a call from Roger Daltrey to do a record. So I did that.

We made Rocks in the Head half here and half at Abbey Road. After that, I got a call from Ian Hunter, and I did a Scandinavian tour with him. There was a long period where I was just trying to see what I sounded like. I didn’t do my own record until 2013, which was Lifer. And at that point, I realized who I was.

The overall sound of Sobering Times is what you’re known for – bluesy, British-inspired guitar rock.

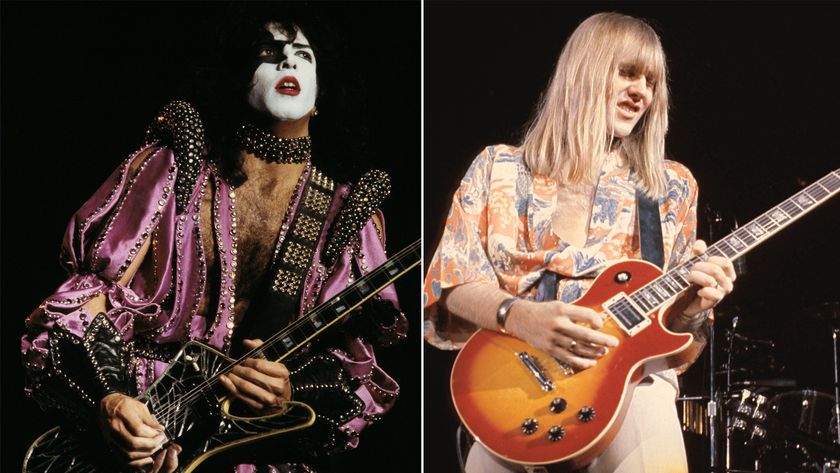

Sure. I’m a product of all the music I listened to as a kid, and I’m not ashamed to nod to my influences. That could be anything from Sweet to the Stones and the Faces.

There’s the Who, the Kinks, maybe a little Dylan and Lou Reed. When I make a record, instead of trying to come up with a new rock-and-roll sound, I’m reverting back to myself as a 13-year-old kid listening to music on my headphones. That’s what makes me happy.

Take me into the nuts and bolts of your guitar sound on the record.

It’s funny. When I was in the Blackhearts, I was a Marshall guy – Marshall half-stacks. Now they’re just too loud for me. My favorite amp these days is a little 15-watt Fender Pro Junior.

The thing is so tiny, but it’s got power. I’ve also got a Fender Champ that I love plugging into. Guitar-wise, I used my ’90s Epiphone Flying V, and there’s my ’75 blue-sparkle Les Paul and my ’73 Les Paul. For 12-string stuff, I played a Denelectro.

I have a ’73 Telecaster, but I can honestly say I’m not a Strat guy. If I’m going to use a Fender, it’s a Tele. For acoustics, I used my ’69 Gibson Hummingbird, an ’87 Martin HD-28 and a 1966 National that has the “Gumby” headstock. Of course, those Marshalls sounded great on “I Love Rock ’n’ Roll.”

Do you ever get tired of hearing that song?

No! [laughs] Of course not. I walk into a store and I hear that song. It’s like, how blessed am I? That’s what I’ve wanted since I was 13. It doesn’t get cooler than that. Anybody who gets tired of hearing themselves on the radio or wherever, I can’t understand that. Things could be worse.

- Sobering Times is out now on Kayos Records.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

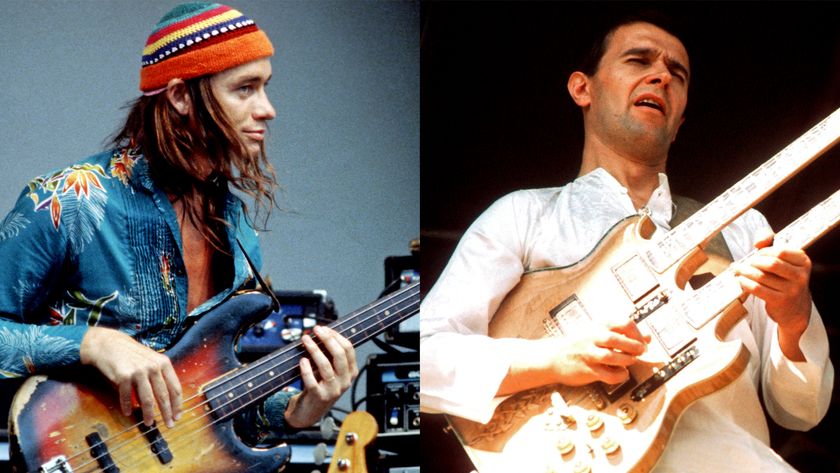

"Jaco thought he was gonna die that day in the control room of CBS! Tony was furious." John McLaughlin on Jaco Pastorius, Tony Williams, and the short and tumultuous reign of the Trio of Doom

“It’s all been building up to 8 p.m. when the lights go down and the crowd roars.” Tommy Emmanuel shares his gig-day guitar routine, from sun-up to show time