Rick Derringer, famous for "Hang on Sloopy" and "Rock and Roll Hoochie Koo," has died. Read our exclusive 2024 interview where he recalled inspiring Eddie Van Halen and performing with Johnny Winter

Legendary rock guitarist and songwriter Rick Derringer passed away May 26, 2025, at age 77. In 2024, Guitar Player contributing writer Joe Bosso tirelessly tracked down the elusive guitarist for a rare interview to discuss his wide-ranging career — from his time as a teen guitarist and singer in the 1960s group the McCoys to his 1970s work with Johnny and Edgar Winter, his solo career, and his later work with "Weird Al" Yankovic and former Beatle Ringo Starr.

Through great persistence, Bosso finally got his interview, which we have reprinted here in its entirety. Derringer proved to be a tough, though generous, subject, taking time to go through the disparate facets of his career and the various musicians he's known and befriended for years.

Rick Derringer was a uniquely talented guitarist and songwriter, whose stylistic range covered everything from rock to fusion to pop. Amid all his work with and for other artists — including Todd Rundgren and Steely Dan's Donald Fagen — he recorded a solo album that remains essential in rock and roll: 1973's All American Boy. If you don't know it, we highly recommend that you become familiar with it. — Christopher Scapelliti, Editor-in-chief

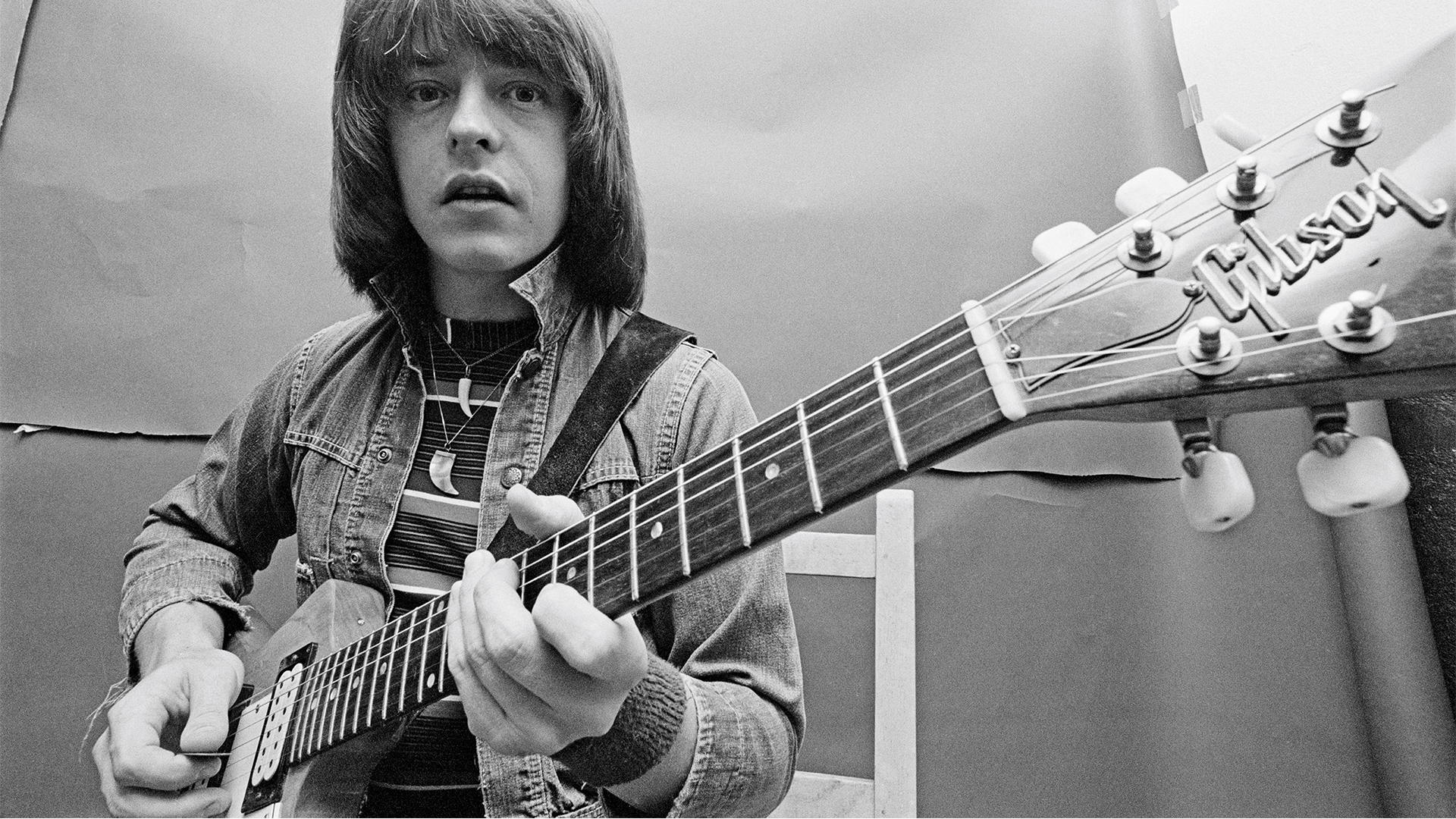

“I was a natural,” Rick Derringer says, dispensing with any pretense of modesty. He’s recalling the time when, at nine years old, in 1956 (the “Year of Elvis,” he calls it), he got his first real guitar — a Harmony-type model with one pickup — and a copy of Mickey Baker’s Complete Course in Jazz Guitar, and how, on his first night he was off and running. “Right away, I was playing chord sequences like a pro. I was totally hooked, and it all came very easily to me. I know some people hate to hear that, but I was just blessed by the good Lord with the ability to play anything I heard.”

Within weeks, Derringer — or as he was known then, Rick Zehringer — was playing country-western tunes in bars in and around his hometown of Fort Recovery, Ohio, with his uncle Jim, a singer and guitar player. “It seemed like the most normal thing in the world,” Derringer says. “What wasn’t normal, at least to me, was the money we made. The first time I played a gig, they passed a hat around and I made $43. This was in the 1950s, so that was a lot of money at the time.”

Country-western ditties were fine for a while, but rock and roll was exploding, and Derringer was enthralled by all the new sounds he heard. “The first record I bought was by Buddy Holly, which, of course, had electric guitar on it,” he says. “There was electric guitar on all the Elvis records. Suddenly, the electric guitar came of age, and it was being used as a lead instrument. People became famous because they could play guitar. You could have a career as a guitar player. That’s what I wanted.”

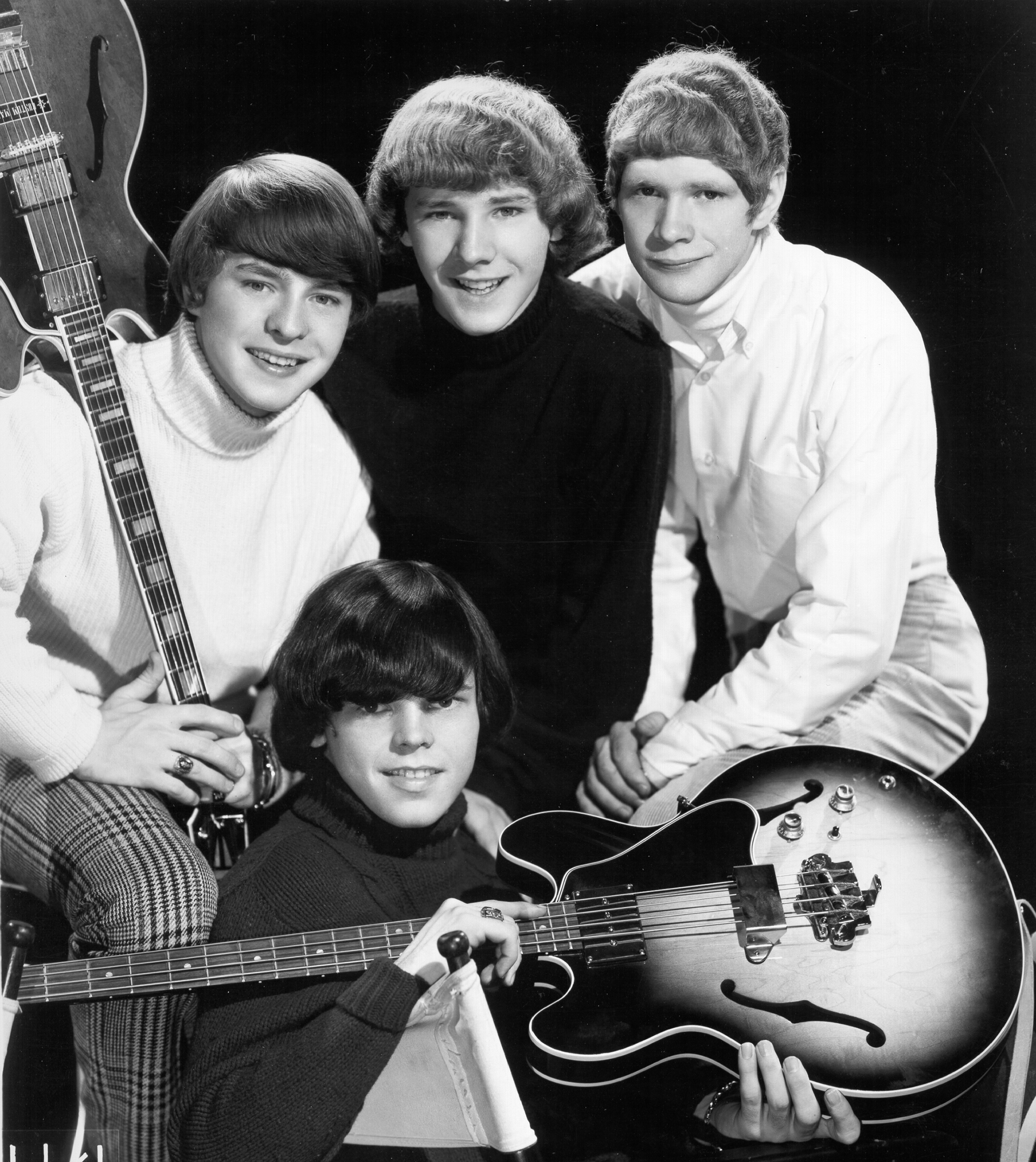

He realized that he needed a band, and after the Zehringer family moved to Union City, Indiana, he formed his first outfit with his brother, Randy, on drums and a neighbor, Richard Kelly, on bass. The group went through a succession of names: First there was the McCoys (inspired by a song titled “The McCoy,” the B-side of the Ventures’ hit single “Walk, Don’t Run”), and next came Rick and the Raiders. Briefly, they were the Rick Z Combo until they finally went back to the McCoys.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

With Derringer fronting the band, the McCoys played around the Midwest and cut a single called “You Know I Love You” that received some regional airplay. By 1965 the group’s lineup had changed — bassist Randy Jo Hobbs replaced Kelly, and organist Bobby Peterson signed on — and they scored a number one single with their vibrant cover of “Hang On Sloopy,” which had been a hit the previous year by an R&B group called the Vibrations.

“People always ask me, ‘Was it an exciting time?’ And I say, “Yes, of course it was,” Derringer says. “It’s difficult for me to have an outside perspective on it, because I was on the inside and I was doing it. Here I was, 17 years old, and I was in a successful band with a hit record, and we were playing all over the world. I was so happy.”

"That’s wrong information. I played all the guitar on 'Hang On Sloopy,' including the solo. That was one take."

— Rick Derringer

By the end of the decade, the McCoys’ career came to a close, and Rick Zehringer became Rick Derringer. But the guitarist’s fortunes rebounded quickly — with the McCoys, he teamed with rising blues star Johnny Winter. “That was the start of what really became my destiny,” Derringer says. “I had no idea of what might lie ahead for me, but now that I look back on it all — the records I’ve made and the people I’ve played with — and it’s pretty remarkable.”

He laughs. “And I was there for every second of it.”

Clear something up for me. On Wikipedia, it says that you recorded your lead vocal on “Hang On Sloopy” over backing tracks by a group called the Strangeloves. It doesn’t credit you as playing guitar.

That’s wrong information. I played all the guitar on “Hang On Sloopy,” including the solo. I sang lead and I also sang as part of the group. The Strangeloves were music producers — shysters, actually, from New York City — and they were in the business of cheating people. They did that very well, but they didn’t play guitar.

Your solo is pretty spectacular, particularly for someone so young.

That was one take. They said, “Now it’s time to play the solo.” I played it, and that was it. I just came up with it on the spot. I used a Gibson ES-355TD, without stereo.

Had you heard the version called “My Girl Sloopy” that the Yardbirds recorded with Jeff Beck?

That was way later. No, I never heard that. The first version I heard was by the Vibrations.

You said it was an exciting time for you. How much so? This was when the Beatles and the Rolling Stones were flocked by screaming girls everywhere they went. Did the McCoys experience the same thing?

Yeah. Yeah, it was like that. I opened for the Rolling Stones on their very first American tour. And, of course, we received the same adulation that the Stones would get. People ask me, “Did you see what it was like to be a Beatle?” Well, I already knew what it was like to be a Beatle. I had the number one record in the world while “Yesterday” by the Beatles was number two. Did I know what it was like to be the Beatles? I was the Beatles in some form. I grew up like that.

"Did I know what it was like to be the Beatles? I was the Beatles in some form. I grew up like that."

— Rick Derringer

What kind of guitars and amps were you using on your early tours?

I played that 355 a lot. I also played a sunburst Les Paul that I liked a lot. As for amps, we hadn't gotten to the era of Marshall amps yet, so I probably played through a Fender Super Reverb. That was one of my favorites. No Twin Reverbs, though — they don't break up so good.

The McCoys were tagged as a “bubblegum” group, but you guys started to venture into psychedelia. Did your label fight you at all?

The label didn't stop us, but we were known as a bubblegum group, which wasn’t a good connotation. Before “Sloopy,” we played R&B, soul, jazz — lots of different kinds of music. We looked at ourselves as a quality musical group, and suddenly we were pigeonholed in a genre we didn’t feel good about.

As soon as our contract with FGG Productions was up — it wasn’t with Bang Records — we chose to get out. Now Bert Berns, the president of Bang Records, he was a pretty good guy. He came to me and said, “If you want to continue with Bang Records and not with those guys, I'll show you how much money they're cheating you out of and make sure that you get a fair shake.” Well, we said, “No, we’ve got to get away from this whole thing.” We got a contract with Mercury, and they allowed us to do anything we wanted. We were on Mercury when I met Johnny Winter. That was the opportunity to get out of that whole genre.

Hooking up with Johnny Winter must have seemed like a left curve to your fans.

It probably was, but it gained me so many other fans. Johnny Winter was signed to the biggest record contract in the history of the music business at that time. He was well received, so suddenly I was playing with a legit guy. That opened the doors for me. He asked me to produce his records.

Now, the thing about his big contract — the label forgot that he was a blues guitar player. Blues didn't sell that many records to warrant so much money. In order to change that situation, they said he has to be more rock oriented. That’s where I came in, to bring the rock ‘n’ roll. The McCoys came with me to join Johnny, but we couldn’t use that name because it had negative connotations, so the band became “Johnny Winter And.”

I was watching a clip of you guys from 1970. Right from the opening song, “Guess I’ll Go Away,” you and Johnny were dangerous on stage.

We had fun. [laughs] It was a contest every night to see who could play the best.

"Johnny Winter was well received, so suddenly I was playing with a legit guy. That opened the doors for me."

— Rick Derringer

In the clip, Johnny is playing an Epiphone Wilshire, and you’re playing a Les Paul. I assume you two tried to blend tones.

A lot of that came from our amplifiers of choice. I was probably using a Marshall, and he had a bank of Twin Reverbs, I think. Eventually, we got to where we were both using Ampegs.

How much room did Johnny give you to solo?

If we’re talking about albums, I would make the rules because I was the producer. If it was live, we didn't have any specific rules. Now I understand from other people that play with other artists that they’re given rules about what and how much they’re allowed to play. We didn't have anything like that.

Johnny was very generous about sharing his blues knowledge. He showed me specific things I didn't know — tunings and slide guitar. It wasn’t because he wanted me to know these things — I asked him. I said, “Help me with these things.”

Johnny recorded your song “Rock and Roll, Hoochie Koo.” Did you have reservations about him singing it at the time?

No. As a matter of fact, that's what I was getting at before. The first thing I did was make sure the music more commercial, more rock oriented. I wrote “Rock and Roll, Hoochie Koo” — the rock was me and “hoochie koo” was Johnny. He was the band leader, so we did it his way. The first opportunity I had to do it my way was on my first solo album, All-American Boy.

We had a great time playing, Johnny and me. It was a kind of competition. Eventually, he got tired of trying to compete, so he disbanded that group, and that's when I started playing with Edgar Winter’s White Trash.

"I wrote 'Rock and Roll, Hoochie Koo' — the rock was me and 'hoochie koo' was Johnny."

— Rick Derringer

How did Johnny feel when you went off to play with his brother? Was there any weirdness about the situation?

By then, Johnny had become engrossed in the drug world and checked himself into rehab. Suddenly, there was no touring, and that ended that band. I joined his brother, and I produced Edgar Winter’s White Trash. That’s when I started playing with White Trash live.

You produced Edgar’s They Only Come Out at Night, which featured big hits like “Free Ride” and “Frankenstein.” What was it like working with Ronnie Montrose? He played the solos on both of those songs.

Ronnie played the solos on the album version of “Free Ride.” I played lead guitar on the single version. I enjoyed working with him. He was a good guitar player. He was very inventive and had a good sense of humor. Ronnie was a brave guy, and Edgar was a very planned-out, nerdy kind of musician. He wanted things the same every time, and Ronnie was the total opposite.

As producer, did you direct Ronnie on what to play, or did you just let him go?

I never showed him anything specific. For instance, on “Frankenstein,” it was like, “Here’s the guitar solo section. Take off!” He'd do his thing, and I was fine with everything he played. Same thing on “Free Ride.” It was “Here’s your part. Just play lead guitar.”

Soon after that album, you had a hit with All-American Boy and your own version of “Rock and Roll, Hoochie Koo.” The guitar solo is strikingly different from the one you did with Johnny Winter.

Oh, yeah. Those are two totally different records. The one I did with Johnny was more in keeping with his style. When I did my version, it was my opportunity to play and create what I thought it could be. I went for it.

Do you remember what your guitar and amp setup was on that track?

I think I was playing, strangely enough, a blonde Strat with a blonde neck, once again through a Super Reverb. It sounded good.

"There were a lot of great guitar players all over the world, but they didn't live right down the street from the studio."

— Rick Derringer

On the cover of All-American Boy, you posed with a red Stratocaster.

That was a photo by the Japanese photographer Hiro. It wasn’t even my guitar — it was Johnny Winter’s. He gave it to me because he didn’t like it. We used it for the cover because it matched the clothing and everything, the silver and red. We thought the guitar looked cool.

Around this time, you began appearing on a lot of other artists’ records. Were they looking for you to do anything in particular, or did they call you solely based on your reputation?

It was pretty simple, really. They’d be like, “Can you come into the studio today and record something for me?” I lived in Manhattan, so I would say, “Yeah, sure.” That’s all there was to it. There were a lot of great guitar players all over the world, but they didn't live right down the street from the studio.

Todd Rundgren featured you on a few albums. Did he have any specifics for what he wanted you to play?

It would depend on the song, I guess. We were friends, and I think he just wanted another name on the record — you know, “I got Rick Derringer on here!” [laughs] I always enjoyed playing with him. On some songs I would just play a harmony with a melody that he had already recorded, or in some cases he would just allow me to go for it.

Was that the case with your solo on his song “Dust in the Wind”? Your lead is so clean and the phrasing is very economical.

Yeah, I probably just went for it. It was spontaneous.

What was your relationship like with the Steely Dan guys?

In the case of Steely Dan, I played on Donald Fagen's demo that was eventually used to create Steely Dan. They kind of knew of me initially, and then I was on the road during the making of their first album. I didn't do that record, but I played a little something on most every album after that, including Donald Fagen's solo record. I was just accessible. They knew I could come in there and play whatever they wanted.

"I played on Donald Fagen's demo that was eventually used to create Steely Dan. I played a little something on most every album after that. I was just accessible."

— Rick Derringer

You mentioned Johnny Winter showing you slide guitar. Your slide playing on “Show Biz Kids” is pretty much the star of the song.

They said that they wanted slide guitar, and they wanted similar things to what I played with Johnny. They didn’t determine the parts, though. I just created the parts.

What about your solo on “Chain Lightning”? It almost sounds like a couple of different players coming in after each other.

It’s all me. I did that whole solo.

What I’m getting at is, Becker and Fagen had a reputation for being kind of taskmasters, doing endless takes.

I didn’t have that kind of experience with them. They pretty much just played me the song — “Here you go, Rick. We want it to be a blues kind of thing.” So that's what I did.

In 1978, you gave a young hotshot named Neil Giraldo his start when you hired him for your band. What is it like mentoring him?

I found Neil to be very useful on a couple of levels. He played really good guitar — really good. He didn't always have to play lead ‘cause I was in the band. [laughs] He'd usually play rhythm, but he played really good rhythm. When we went into the studio to record Guitars and Women, I found out that he also was a pretty good piano player, so he played some piano on that album.

Mike Chapman was working on a record in the same studio. He called me and said, “Rick, would you mind if I used your guitar player on this record?” Not thinking logically, I said, “Sure, why not?” It turned out that record was by Pat Benatar. Neil and Pat met, and that was that. They became husband and wife, and they’re still together today.

"He said, 'Rick, would you mind if I used your guitar player?' That record was by Pat Benatar. Neil and Pat met, and that was that."

— Rick Derringer

I interviewed Neil recently and he said great things about you. He did tell me, however, that you were a little tough on him after the first live gig he did with you.

That's what he tells me. Maybe I meant that he had to be more of a performer — I don't know. I don't remember that incident, but he tells me that, too.

A lot of people might not know you’re playing the solos on some big power ballads.

Yeah, I played on Bonnie Tyler’s “Total Eclipse of the Heart” and for Air Supply I played on “Making Love Out of Nothing at All.” That’s one of my favorite guitar solos.

That’s so surprising.

Oh, well, I really enjoyed playing that solo. It has kind of a classical music beginning, but it’s not me showing off. I’m just playing music. It’s very heartfelt. I like it.

Can you talk a bit about working with “Weird Al” Yankovic?

A lot of people were like, “What’s Rick doing?” You know, I had a pretty good production career going for myself, so it didn’t strike me as unusual to work with Weird Al. I grew up in a family that liked novelty music. They had 78s of Spike Jones and stuff like that. When I was approached to a single with Al, I said, “Do you have more songs like this?” He said yeah, so I said we should do a whole album. I thought, “If we can make a success of his songs, it would have no competition.” Because there wasn’t anything like his stuff out at the time.

I produced his first album ["Weird Al" Yankovic, 1983] out of my pocket — there was no record company support at all. We made a great record and sold it to this label, Scotti Brothers. The Scotti brothers were in record promotion, and they had just started a record company. There were other record companies that wanted the album, but I told Al, “If the Scotti brothers take it, you'll probably be cheated, but you'll probably be guaranteed of having a hit because these guys are good at what they do.” We released it on the Scotti Brothers, and it was an instant hit.

Al was at the advent of MTV. He knew what he was doing. I left him after six albums, two Grammys and two stars on a Hollywood Walk of Fame. He's done very well. But here's the bottom line: I thought that it would help my production career, but suddenly I became known as a novelty producer. As much as I love Weird Al — he's a good guy, very talented and a hard worker — he single-handedly ruined my production career.

"As much as I love Weird Al — he's a good guy, very talented and a hard worker — he single-handedly ruined my production career."

— Rick Derringer

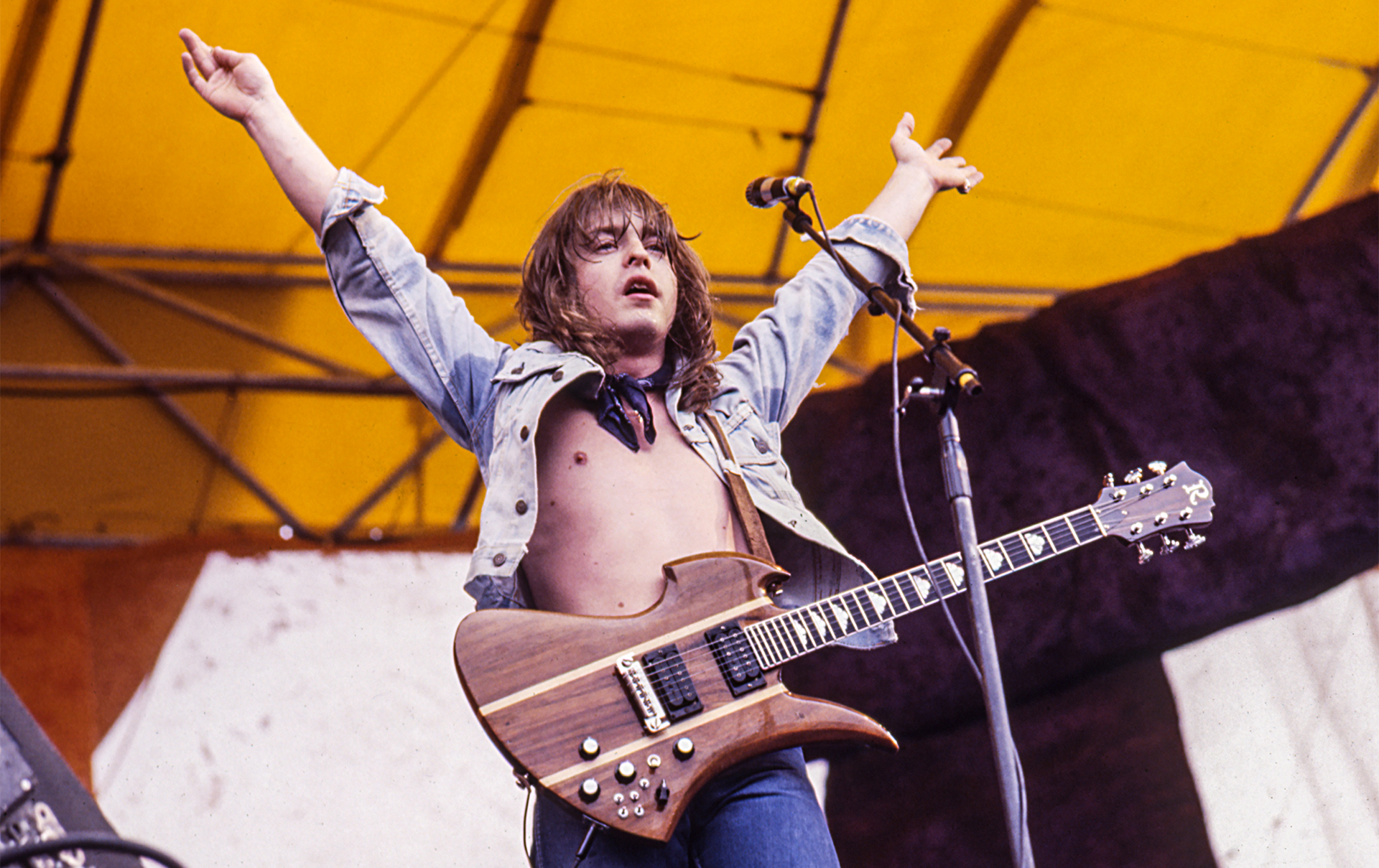

You played some cool guitar on his records, particularly on “Eat It.” Obviously, you were emulating Eddie Van Halen’s solo.

I was. I played it on a B.C. Rich. What’s interesting is, Eddie told us that he copied that style from listening to us. The guitar player in the Rick Derringer band was Danny Johnson, and I asked him to play with us because he was one of the first people I ever saw who did that style. That was one of the reasons he got the gig. Eddie Van Halen said he was a big fan of that band, and he came to see us play regularly.

Did Eddie ever tell you what he thought of your “Eat It” solo?

He didn’t. He never talked about it specifically.

What was it like playing with Ringo Starr and his All-Star Band? You did a few tours with him?

It was fun. The whole band was fun. Gary Wright, who just died recently, was a keyboard player. Edgar Winter was in the band. He played keyboards and sax. Wally Palmer from the Romantics was the other guitar player. It was a little funny, though. You know how I said that “Hang On Sloopy” was number one and “Yesterday” by the Beatles was number two? Well, on the tour, I told that story for the first few shows and then I’d play “Hang On Sloopy.” After the third show, a roadie came up to me and said, “Did you get permission from Ringo to tell that story?” I said, “No, Should I?” And he said, “You probably should.”

"He said, 'Did you get permission from Ringo to tell that story?' I said, 'No, Should I?' And he said, 'You probably should.'"

— Rick Derringer

What happened?

I went to Ringo's dressing room, and he graciously admitted me. I told him, “You've been sitting right there behind me every night, and you've heard me tell that story. Is it okay with you?” And he said, “I didn't play on either one of them.” [laughs] That was his answer, so I guess it was okay. But then I limited my telling of that story, just because I rethought it and said, “I'm playing with Ringo. I don't really need to tell that anymore.”

I saw a clip of you and Edgar playing “Frankenstein” with Ringo’s band. You pretty much re-created Ronnie Montrose’s parts.

Yeah, pretty much, because you know, that’s what people know. We would extend the song, so I didn’t play it the same every night.

Recently, you released a new album called Rock the Yacht on which you and your wife, Jenda, share vocals. Despite its title, it’s more of a pop album with big ballads.

It's a progression of everything that I did in the past to now. People would like me to continue playing the music that I played when I was a teenager or when I was in my twenties. They want me to rock ‘n’ roll over and over like a young guy. But I’m not a young guy — I'm a 76, so we do grow older and our musical tastes change a little bit. Rock the Yacht reflects a new version of who Rick Derringer is, who he's become, and what the music is. I really enjoy it. You can get it anywhere that sells music.

What kinds of guitars are you playing these days?

I play mostly Warrior Guitars. Their guitars are fabulous. I started playing them probably 20 years ago. I've got a Warrior called Isabella that looks kind of like a Les Paul. That’s my main guitar, and then I have one that looks like a Strat — it doesn’t have a name. I just asked them to make me a Strat-style guitar. It doesn’t have a bolt-on neck, though. They’re excellent guitars, all handmade.

You’ve cut back on shows. Do you plan to do much touring in the future?

I don’t like the rigors of touring — getting up in the morning and riding to the airport in some kind of group van or on a group bus. I don't like the TSA. I played a gig a while back with Neil Giraldo and Pat Benatar, and I had a great time. But you know, there’s been so many changes in the business. You don’t actually make money from records; you make it on touring. I toured from my teen years till the time Covid shut us all down, and now I understand the good parts of retirement. I doubt I’ll ever tour like I used to again.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.