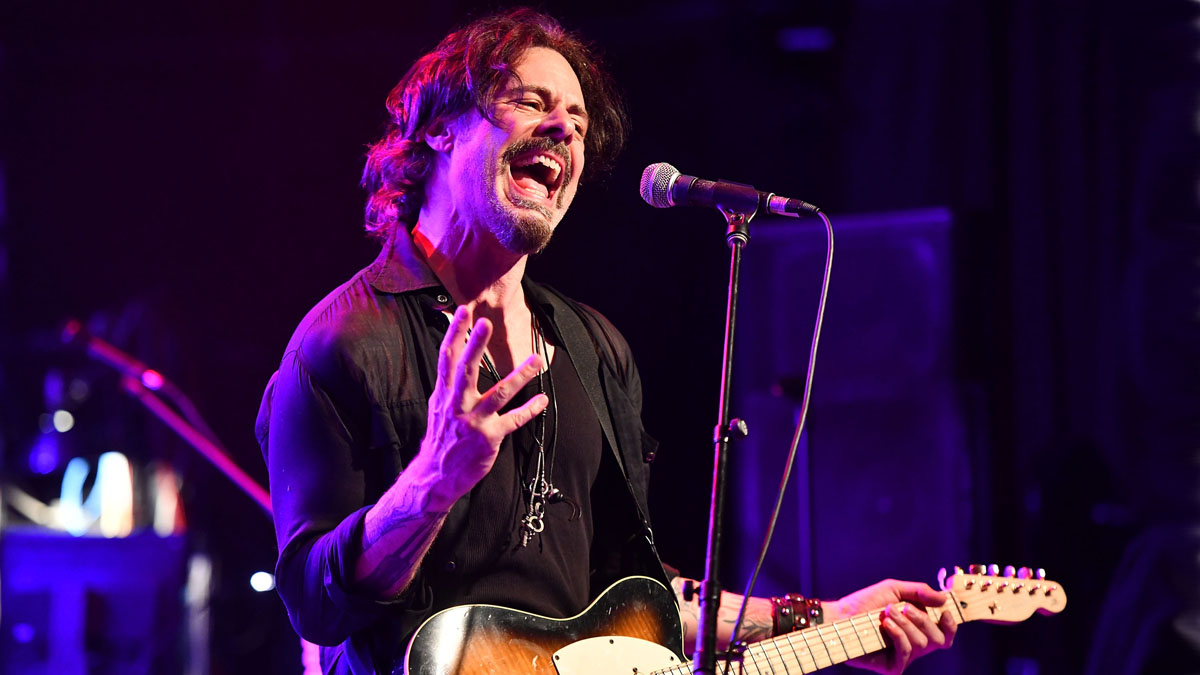

Richie Kotzen Tells the Epic Story Behind His Magnum Opus

For Kotzen, 50 is the new 50 as he celebrates his birthday with his biggest record ever.

Richie Kotzen isn't really a guitarist. That will probably be news to anyone who knows his Shrapnel work at the dawn of shred, or his awesome playing on his 22 solo albums, or with the Winery Dogs.

But it’s actually not accurate to call Richie Kotzen a guitar player. Rather, he’s a soulful multi-instrumentalist singer-songwriter who just happens to be really, really good on guitar. And he didn’t have anything left to prove on the instrument way back in the 1990s.

So what does a guitar hero do when he doesn’t care about being a guitar hero anymore? Write songs. Lots and lots of songs. For Kotzen, songs are like lava in a volcano - it’s probably better to get them out regularly and peacefully, otherwise there might be some kind of explosion.

That steady, prolific output has fueled his many solo efforts, and it’s what made him the primary songwriter in his stints with Mr. Big and Poison. Dude’s gotta write, and so that’s what he does, although he tours so relentlessly that it’s reasonable to ask, “When do you even find time to write songs?”

The least amount of obstacles that you can present yourself with as a writer, the more prolific you can be, and the more honest you can be with your music.

It’s hard to believe that the eternally youthful Kotzen is a quinquagenarian, but it’s true, and he decided to ring in his half century on the planet in bold fashion.

Despite having an album’s worth of material ready to go last year, he pondered the poetic, but logistically daunting title of 50 for 50, and that led to the awe-inspiring, three-disc record that he released on his 50th birthday.

Good luck picking a set list on your upcoming tours, Mr. Kotzen. 50 for 50 is an astounding accomplishment that features his smoky, Philly soul–inflected vocals over the top of deep grooves, clever bass lines and - surprise! - a metric ton of thrilling guitar work from a guy who doesn’t practice guitar anymore.

This is a big undertaking. Did you ever say to yourself, “Why didn’t I just call it 20 for 50!?”

Ha! Great question. I pretty much had what would’ve been a normal record - 14 or 15 songs that were finished that I liked. While I was on tour, I had a drive with some incomplete songs that just needed a little bit of attention.

Some were nothing more than a click track, a bass line and a guide vocal. Some were a guitar riff or a keyboard part. I started thinking that I had more than enough material there to do what I wanted to do, which was release 50 songs on my 50th birthday.

I took some notes and I wrote some lyrics. I came home and had about three months of downtime, so I went into the studio to see how much I could finish. I knew once I got in there that I would start coming up with new ideas, and I did.

Right before I left for my South American tour, I got to 50 songs. There are four songs on there that were finished in the early 2000s but never released, and then there are a few songs that are only a couple of months old.

Stylistically, what are the challenges of having songs that were recorded 20 years apart sit side by side?

A big reason why some of this material sat for so long is that certain songs didn’t fit stylistically into a traditional 12-song album. Some of them just didn’t make sense for me at the time. But when you’re doing a three-disc, 50-song record, that whole sentiment kind of goes out the window.

Because it’s such a broad scope of music, to me it becomes okay to have a song that might be a little bit of a throwback to my instrumental Shrapnel days, and maybe another song that’s just a church organ and a voice. I didn’t get too caught up in what fits and what doesn’t.

My only concern for each composition was, 'Is this worthy of being shared? Does it represent something personally to me?' That was my barometer for these songs.

What about from a key-center standpoint? Would you avoid two songs in a row that are in the same key?

The least amount of obstacles that you can present yourself with as a writer, the more prolific you can be, and the more honest you can be with your music. I think when you start thinking about technicalities like tempos and keys, you’re not necessarily thinking about the song.

For me, the song really is the lyric and the melody. You can strip away everything from [the 50 for 50 track] “Devil’s Hand” and the song is still there - the melody, the lyric and the storyline. How you wrap everything else around that is your creative choice. If I start coming up with parameters that are unrelated to the sentiment, the meaning and the story of the actual song, that’s going to create obstacles for me.

In terms of sequencing, I did do something with the song “Stick the Knife.” Just by the nature of how it starts - with that guitar part and the big power chord - I knew it was going to be the opening song. It just felt like an album opener to me. So that slot was always filled with that song, and everything else flowed naturally from there.

“Stick the Knife” is a very powerful opening statement. Can you explain what’s going on from a technical standpoint in the intro? Are you hitting the same note on different strings at various points?

You bring up an interesting point. A lot of times I do double notes, and it usually happens across two strings, like across the third and fourth strings. I may play a G on the G string and then play a G on the D string back to back, and that’s what you’re hearing.

Those lines come naturally to me, just because of the shape and the size of my hand, although this one took some work. The opening line is a fingerstyle thing where I’m playing one note on each string across three strings very quickly.

From there, I take off into a descending, partially legato, partially finger-picked line. I do play with a pick for lots of parts on this record, but that intro is one of those things that’s really only possible fingerstyle.

Talk about “As You Are.” You get a really nice bass tone in that song. What’s the key to making bass and guitar sit next to each other nicely in a mix?

People can make the mistake of thinking, Well, I can’t hear the bass, so there must be something wrong with the tone. A lot of the time it’s not that. So much of it has to do with what the instrument is playing and when the instrument is playing, as opposed to its tone.

I think it’s how the counterpoint is working that allows everything to be heard. In this song, the bass is following the guitar, but it’s also speaking when the guitar isn’t. It’s that kind of communication that allows both instruments to speak clearly. That’s really how I hear things when I’m writing.

I’ll hear the vocal melody first, and the next thing is the drumbeat. I always know what the drums are going to do once I have the melody because they’re connected for me. I can build everything else around that. If I do it right, they work together like puzzle pieces.

What’s your recording process? Did you have a go-to rig for your guitar parts?

The way I work is this: Everything I use is already miked up and set, and that signal chain doesn’t change. The microphones and preamps I have on the drum kit are always up and always routed.

Same thing for bass; same thing for guitars. I can record a song and then, a week later, if I decide I don’t like a guitar chord or a drum fill, I can fix it and not have to worry about the sound changing. Some of these parts were recorded over the course of 15 years or more, in a variety of studios, so it would be almost impossible for me to know exactly what gear I used on every track.

But for the newer stuff that I did here at my place, Victory made me a really nice 100-watt head that is very clear and clean, and that was the main amp. I could color it however I like with my Tech 21 Fly Rig, which is very versatile. I have a 2x12 cabinet downstairs with Celestions in it.

I always use an SM57 for the close mic, and I would add one of the overhead mics from the drum kit for a bit of ambient sound. I’d pan those left and right for a wider stereo picture. Some of the older tunes used a Fender Vibro-King and a Bassman, and I had a little Marshall 20-watt head.

My main guitars were my signature Telecaster and my signature Strat. Beyond that, I have a Yamaha hollowbody that I use for textures. On “Devil’s Hand,” there’s a long solo at the end, and I played that Yamaha on the recording, even though in the video I’m playing a ’70s Thinline Tele.

Let’s talk about “Devil’s Hand.” I watched that video many times, and that solo at the end is a very intricate guitar solo. You’re scatting along with your guitar licks, which really swing, and have all these funky stops and starts.

The video is completely synced up to the recording. It certainly looks like you’re playing live. Did you memorize the solo that you played in the studio and recreate it for the video?

Actually, I did. In the past, when I’ve done music videos, I don’t think I’ve ever really bothered to learn the solo. I would just kind of go for it and then in editing we would be able to choose clips that looked somewhat close.

But for this, because it was such a long scene with that outro solo, I thought it was really important to have accurate footage. So I went through, and learned as much of it as I could. There are a few parts that I may not have learned perfectly, so we would edit around that, but for the most part, I learned the solo.

It’s an amazing accomplishment. Your playing is spot on, and your singing is as well.

The solo was an interesting thing to do, because when you’re doing that scatting thing, it all has to happen at once. You can’t go back and add the scatting later. I had a Neumann U87, which is my main vocal microphone, and that was live, and I was tracking guitar through an amp, which was in another room. But you can hear the acoustic sound coming off that hollowbody Yamaha that the vocal mic is picking up, so it’s an interesting tone.

I’ve often joked that I might have 22 solo records but I’ve really only written 11 songs... There are themes that come up over and over and that’s part of what defines me as an artist

I really just kind of went for it for that solo. The entire thing wasn’t one take, but it was one pass in the sense that I would play for however many bars until maybe I made a mistake or stopped for some reason. Then I picked it back up and kept going, so for all intents and purposes it is a single take. I didn’t go back and fix anything in it.

You haven’t chased after chops for a long time, and yet you’ve always had massive chops. Do you practice at all?

I really don’t. I just play enough so that my chops are what they are. What drives me is the creative process. I’ll noodle around and if I come up with an idea for a song, then I dive in fully.

What will happen on certain songs, like “Stick the Knife,” is I’ll hear a line in my head and think, 'Okay, how can I play this?' At that moment, I’ll find myself practicing. I could not physically play that intro passage that I heard in my head, and so I did practice until I got it under my fingers and was able to record it.

You’ve always taken your songcraft very seriously. Do you have any advice for struggling songwriters?

Trying to tell somebody how to become a writer is kind of tricky, because it’s such a personal thing and I really only know about my own experience with it. But I will say this, and I think this is really important: I’ve been in a room with people I would refer to as creativity killers.

Let’s face it. For the kind of music that I do, I’m not reinventing the wheel. There are a lot of elements that are influenced by things that have happened in the past, although that’s not to say that I’m not doing anything special or unique. But when you’re in the room with someone and you come up with an idea, and before the idea even comes to fruition, they start singing a melody from a famous song over the top of it, that stops it right in its tracks. It’s over. You just want to leave the room.

Where I’m going with this is, I think you have to follow through. You have to remove the element of judgment until there’s something finished - a complete thought. At that point, you can decide what you think about it.

But I think a lot of people put a wet blanket over an idea before the spark has a chance to even develop. And that’s self-defeating. I would suggest that if you feel like you’re having a hard time, trust yourself. Don’t be embarrassed. Write the words, even if they feel like they’re too personal.

Follow it through to the end, and then maybe you can judge it. Maybe you don’t like it, or maybe it turns out to be something really great. But I think some people stop themselves and never get to that point.

I’ve often joked that I might have 22 solo records but I’ve really only written 11 songs. I’m kidding, of course, but there are themes that come up over and over in my music, and that’s part of what defines me as an artist, just as something else will define another artist’s work.

If someone is excited about a chord progression, even if it’s been done 1,000 times, they may have a spin on a lyric or melody that takes it to a whole other level that is unique and fresh. You can’t put limitations on the creative process. You’ve just got to let it evolve.

- Richie Kotzen's 50 for 50 is out now via CD Baby.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened