“I used to fall asleep with it on my chest — it’s literally a one-of-a-kind, unreplaceable keepsake": Randy Bachman on the trauma of having his prized 1957 Gretsch 6120 stolen and the remarkable story of how he was reunited with it

Stolen 45 years ago, the tale of the Gretsch's global journey is now the focus of a new documentary.

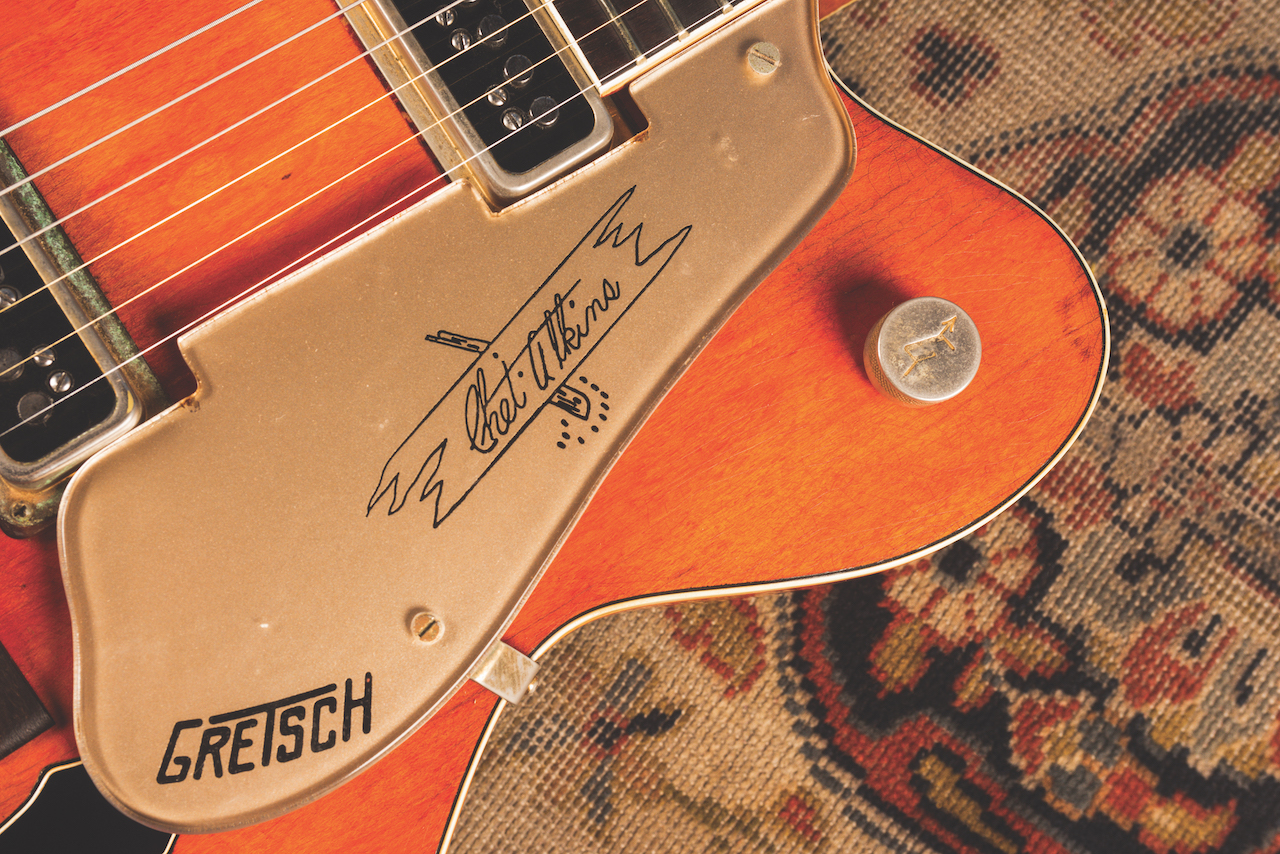

As a guitar-obsessed teenager in Winnipeg, Canada, in the late 1950s, Randy Bachman would make weekly Saturday pilgrimages to the local music store, Winnipeg Piano, which is where he met two lifelong friends. One was another budding area musician named Neil Young; the other, a used 1957 Gretsch 6120 Chet Atkins Hollow Body electric guitar that would become his closest and most treasured musical companion. “Neil lived on one side of town, I lived on the other, and we would both take the bus downtown and look in the window of Winnipeg Piano at this guitar and go, ‘Man, if we could ever play that...’”

Bachman, now 80, recalls. “We had seen Duane Eddy play ‘Rebel Rouser’ with a 6120 on American Bandstand, but that was black-and-white TV, right? So when we saw the actual guitar in the window, and it’s orange, it’s in the sunshine, it’s glowing… It was stunning.” Bachman bought that stunning Gretsch, managing the $400 price tag with money he earned mowing lawns, babysitting, delivering newspapers “at six-in-the-morning in 40-below-zero weather” and doing other odd jobs.

Young, meanwhile, picked up another ’57 6120 that came into the store around the same time. “In the middle of ’57, Gretsch switched from DeArmond pickups to Filter’Trons,” Bachman says. “So I bought the DeArmond one and Neil bought the Filter’Tron one. He took that guitar and played it with Buffalo Springfield on American Bandstand.” Bachman did okay with his Gretsch as well.

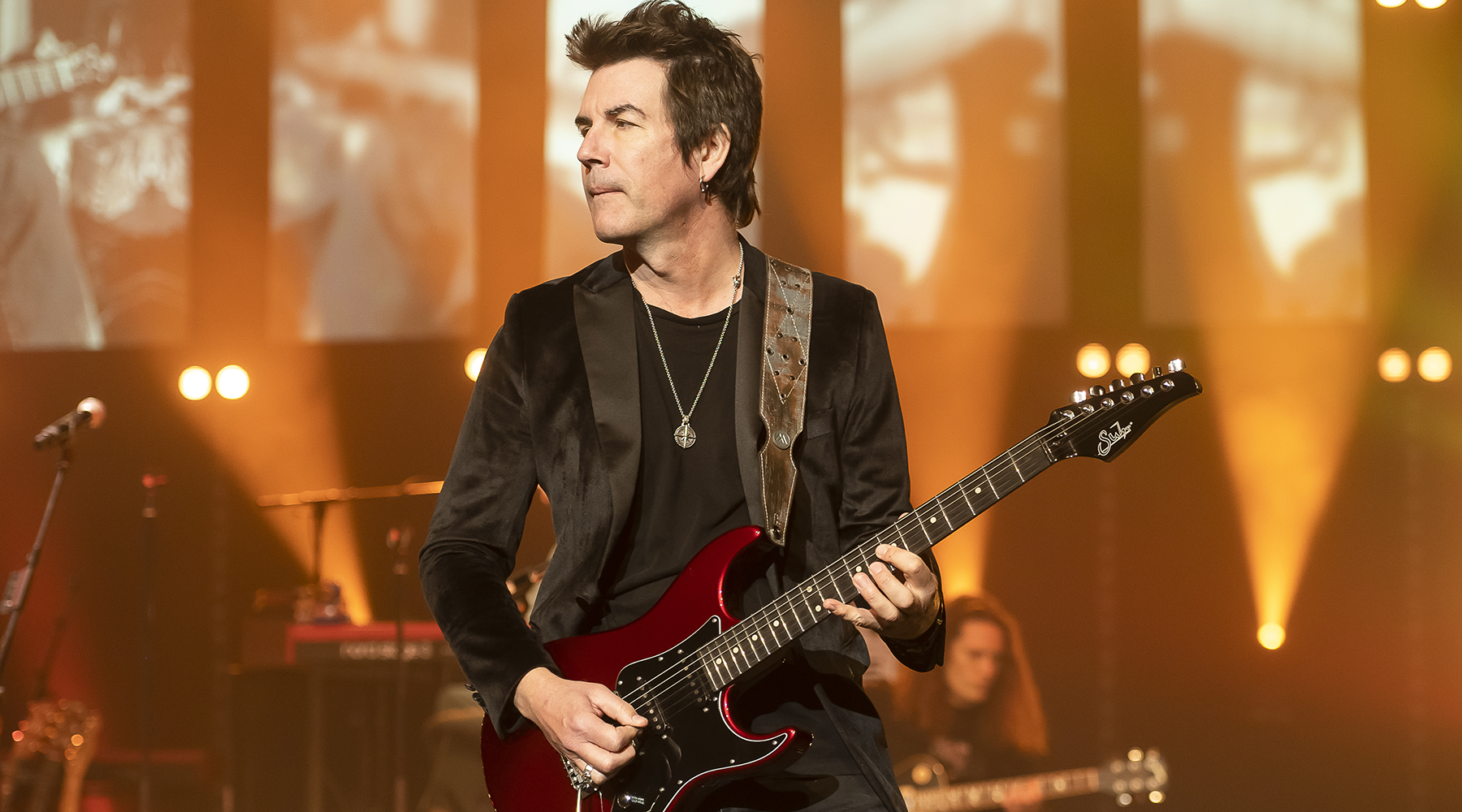

After playing in several local bands, he joined local-area group Allan and the Silvertones, who went through several name changes, scored a number one hit in Canada with their version of Johnny Kidd & the Pirates’ “Shakin’ All Over,” and ultimately solidified as the Guess Who. Bachman played his 6120 on that chart-topping recording and employed the guitar in the writing and recording of a subsequent string of classic Guess Who albums and hit singles, among them “These Eyes,” “No Time,” “Undun,” “No Sugar Tonight” and the indelible “American Woman.”

After parting ways with the Guess Who in 1970, Bachman formed the hard-rocking Bachman-Turner Overdrive and continued his charmed collaboration with the 6120. He penned more hits — “Let It Ride,” “Roll On Down the Highway,” the classic-rock radio staples “Takin’ Care of Business” and “You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet,” and others — and recorded numerous Gold- and Platinum-selling albums.

“From the moment I got that guitar, it was like Dumbo’s magic feather to me,” he says of the Gretsch. But one day in 1976, that magic disappeared — literally. For years, Bachman had routinely gone to extreme, almost comical lengths to keep the Gretsch safe on the road. He describes an elaborate process of securing the guitar to hotel-room toilets via a combination of sandbags, tow-truck chains and two bike locks, “so if somebody wanted to steal it, they had to rip the toilet out of the wall or have a hacksaw, which most guys don’t when they’re stealing from a hotel room,” he says.

It was gone. I felt like somebody had cut off my hand

Randy on his Gretsch 6120 being stolen

But after he left the Gretsch in the care of a roadie while checking out of a Toronto-area Holiday Inn, the guitar vanished. “The roadie said to me, ‘I left it in the room, I went to pay the bill, I came back, it was gone,’” Bachman recalls. “I felt like somebody had cut off my hand.” Thus began a years-long, and ultimately unfruitful, search for the 6120, one that pulled in the Canadian Mounties, the Ontario Provincial Police, vintage instrument dealers throughout Canada and the U.S., pawnshops, mom-and-pop stores, private collectors, mainstream music magazines like Rolling Stone and, basically, anyone that Bachman could tell his story to in the hopes of garnering the slightest lead on his Gretsch’s whereabouts.

The guitarist was distraught and unable to sleep. He received a call from Chet Atkins — one of his idols and the man most closely associated with the 6120 — during which the legendary picker empathized with Bachman’s loss. Afterward, Atkins surprised him with a brand-new Gretsch Atkins Super Axe prototype, but even that couldn’t fill the “giant, Grand Canyon–sized hole in my heart,” he says. And so Bachman filled it another way, spending the ensuing decades purchasing every Gretsch he could get his hands on.

Fans even began bringing their old Gretsches to shows, which Bachman would buy on the spot for a few hundred dollars or less and have shipped home. His searches and purchases led him to rare models, unique finds, one-of-a-kind prototypes, and more than a few 1957 6120s — just not his 1957 6120. Eventually, he had amassed upward of 350 examples. “I ended up,” he says, “with the world’s largest Gretsch collection.” When the Gretsch family regained control of the brand from Baldwin in the mid-1980s, new president Fred Gretsch approached Bachman about using his collection as a basis for re-creating storied guitar models. “There had been a huge factory fire years earlier, and he had no templates,” Bachman says.

“So Fred flew to my house in White Rock, B.C., and said, ‘Can I borrow your guitars, one or two or five or six at a time, and copy them?’” The result was that “almost every Gretsch you see now is a copy of one of mine,” Bachman posits. What’s more, his collection was quickly increasing in value. “In the late ’80s, the Traveling Wilburys came out, and all of a sudden these legendary guys are playing Gretsches — they’ve got Country Gentleman and Sparkle Jet and orange 6120 models,” he explains.

“Now my guitars that I paid 250 bucks for are suddenly $2,500. A year later they’re $12,000. They just go up and up because there aren’t that many around. Combined with Fred Gretsch copying my collection, it was a Cinderella story for me.” But that story was far from over. Eventually, Fred Gretsch asked Bachman to sell him the entire collection outright. “Fred said, “They’re my history. Can I buy them?’” Bachman recalls. “And I sold him all 350 of them, which are now in his museum in Savannah, Georgia.”

By then, Bachman had moved on to another obsession: midcentury German hand-carved archtops. “I got one for Christmas one year and I went, ‘Wow, this is amazing! It’s so light.

Plays so great. Look at the neck joint — it has a screw and a bolt, like a church key. What is this?’ It was a Hoyer, and I fell in love with that guitar,” Bachman says. With help from his daughter, who speaks a bit of German, Bachman began buying up German archtops online. “Every night we would go on German eBay, find an old guitar, buy it for 300 or 400 Deutsche Marks, get it home and go, ‘This is incredible!’” Bachman says.

From the moment I got that guitar, it was like Dumbo's magic feather to me

Randy on writing classics on his 6120

Soon, he had procured well over 100 of these instruments. “And they’re all hand-carved, with beautiful wood, incredible bindings, unique features like lightning-bolt f-holes, scalloped tops. And with wonderful stories — I’ve got pictures of fathers and sons and grandfathers making them in their attics or little sheds on their farms, with wood from the Black Forest. They’re all so unique. I have 150 of them on display now in Calgary, and they’re going to be auctioned by Julien’s.”

As for what drives his guitar thirst? “I’m an obsessive collector, what can I say?” Bachman explains, and then takes a friendly dig at his old Winnipeg mate. “I mean, collecting guitars is easier than collecting cars, right? Because Neil Young does that, and now he has three barns full of ’em!” But at the end of the day, all the Gretsches and German archtops Bachman procured over the years were only a Band-Aid for the guitar that got away.

A 1957 Gretsch 6120 Chet Atkins in Western Orange with a Bigsby vibrato and black DeArmond pickups is already a highly valued and incredibly rare find — fewer than 40 were actually produced in that year. Add in the special bond Bachman shared with the instrument — “I used to fall asleep with it on my chest,” he says — and it’s literally a one-of-a-kind, unreplaceable keepsake."

Decades on from that Toronto Holiday Inn in 1976, it appeared lost forever. Until it wasn’t. In 2019, a neighbor of Bachman’s in White Rock named William Long reached out to him online. A Bachman fan and something of an amateur internet sleuth, Long had undertaken his own search for the missing 6120, “and one day a message came in that said, ‘I found your lost Gretsch guitar,’” Bachman recalls. “So we called this guy and he said, basically, ‘I watched the video for [the 1975 Bachman-Turner Overdrive single] “Lookin’ Out for #1” on YouTube, which shows you playing the Gretsch. And then I Googled every other orange Gretsch 6120 sold on the internet in the last 15 years.’”

Employing retooled facial-recognition software to help him identify and match unique wood grain patterns and distinctive wear-and-tear and markings, Long spooled through hundreds of internet photos and videos and eventually matched Bachman’s 6120 to a guitar in an obscure 11-minute YouTube clip of a man and a woman performing songs like Johnny Marks’ “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree” in a Tokyo bar, the man strumming what appeared to be the long-lost Gretsch.

That man, it turned out, was a well-known musician and songwriter named Takeshi — “he’s like the Japanese Brian Setzer,” Bachman says — who had purchased the 6120 in a Tokyo guitar shop eight years earlier. A video conference call, brokered by Takeshi’s PR rep and Bachman’s Japanese daughter-in-law, Koko, was quickly set up, allowing the two musicians to meet and for Bachman to lay eyes on the 6120 for the first time in more than 40 years.

“I look at it, it has the same little blemish by the master volume control on the cutaway. It’s my guitar,” Bachman says. “It took my breath away. And Takeshi tells me, ‘Well, I’m an honorable man. I’ll give you back your guitar.’ I told him I’d give him a new Gretsch as a replacement. He said, ‘I don’t want a new Gretsch. It must be another ’57. No mods, no repairs, nothing.’ And I go, ‘Are you kidding?’” But if anyone knows how to fi nd a rare Gretsch, it’s Bachman. With help from Gary Dick at Gary’s Classic Guitars in Ohio, he procured an all-original 1957 6120 with DeArmond pickups — no Filter’Trons — and a serial number “two digits off from mine,” he says.

One day a message came in that said, 'I found your lost Gretsch guitar'

“I told Takeshi, ‘Not only do I have you a ’57 Gretsch, but it was made in the same week, probably by the same guy. It’s a puppy from the same litter.’” And so, with replacement guitar in tow, Bachman headed to Japan. On July 1, 2022 — Canada Day — he and Takeshi met onstage at the Canadian Embassy in Tokyo, where, in a special ceremony, the two exchanged Gretsches (and hugs), told stories and even jammed together on BTO’s “Takin’ Care of Business” and other hits. The moment was an extraordinary one for Bachman. But it wasn’t until later that night that he truly reconnected with the 6120.

“At two in the morning, back in my room, I opened the case and put the guitar on a chair,” he says. “And I said to the guitar, ‘Hello, old friend, it’s been a long, long time. You’ve got some wrinkles and cracks. So have I. Let’s play.’” Bachman then proceeded to “play every song I ever learned on it, every song I wrote on it. I played for over two-and-a-half hours, until I was all played out.” He pauses. “Then I started to play something else. And I said to the guitar, ‘Are we making up another new song?’

I took out my iPhone and I started recording. And I called the song ‘Shadows of Yesterday.’” If this turn of events sounds almost too perfect to be true, seeing is believing. And amazingly, Bachman has the entirety of his reunion with the 6120 — from speaking with Takeshi on video conference to their emotional onstage meeting in Japan — preserved on video. “

"We were filming everything for YouTube, so we have all this footage,” Bachman explains. The material has now been compiled into a new documentary, Lost and Found. Directed by Tyler Measom, the fi lm has recently been completed. “It should be shown at Sundance,” Bachman reports, “which is coming up next spring, and then the Toronto International Film Festival, the Tokyo International Film Festival — because they’re crazy over this thing in Japan — and anywhere else we can show it,” he says.

And the song that closes Lost and Found? The newly penned “Shadows of Yesterday.” “My son [musician Tal Bachman] said to me, ‘Dad, let’s be real — with this guitar you wrote numberone hits. And you haven’t had one since,’” Bachman says. “I told him, ‘Yeah, but I’m not chopped liver!’ “So now that I have the 6120 back, there are more songs. And maybe something magical will happen. And it doesn’t have to be with a song. Even if it’s getting a number one on Rotten Tomatoes for the documentary, the guitar will have done its magic one more time.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

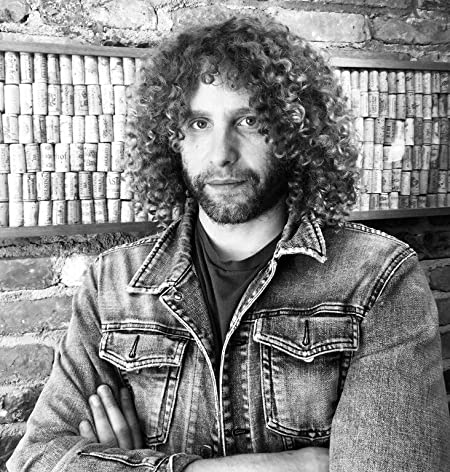

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened