Punk Guitar Legend Dr. Know Revisits the Profound Legacy of Bad Brains

The pioneering guitarist tells his story of the Washington D.C. band that redefined punk.

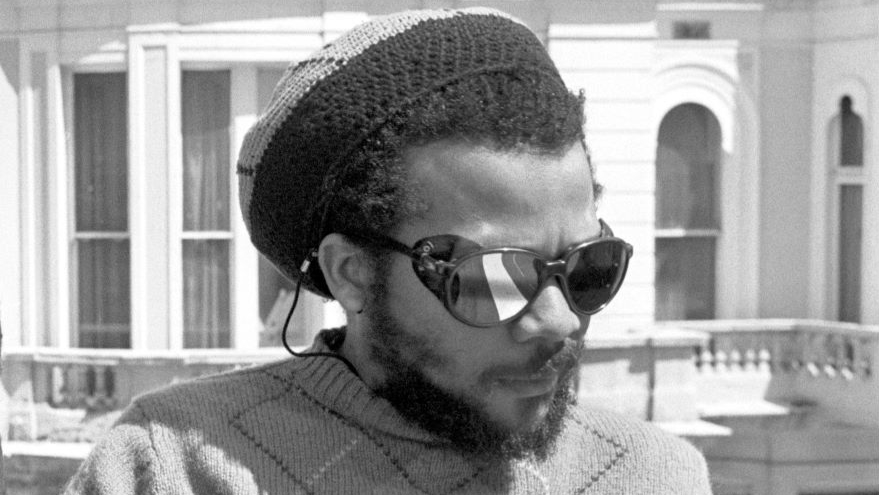

When Gary Miller graduated from high school in the late 1970s, the Washington, D.C. guitarist – better known as Dr. Know of the seminal hardcore group Bad Brains – was not planning on a lifetime career in rock and roll.

“I was going to Maryland University and I wanted to be a doctor,” the 61-year-old says from his home in Kingston, New York, where he is still working to undo some of the effects of a severe stroke he suffered in 2016. “That’s how I got the nickname ‘Dr. Know,’” he adds.

Of course Doc, as his bandmates call him, was not to finish his medical studies but to devote his life to his musical craft instead. “That’s how the spirit works,” he says. “It’s like, ‘All right, you boys are going to come over here and play this music.’”

I was going to Maryland University and I wanted to be a doctor

Dr. Know

Whether guided by divine forces or their own talent and vision, Bad Brains went on to become pioneers of hardcore punk. Formed in 1977 by Dr. Know, bassist Darryl Jenifer, vocalist Paul Hudson (known to most as H.R., an acronym for Human Rights) and his brother, drummer Earl Hudson, the group made a biblical impact on almost every punk and hardcore band that followed, particularly local D.C. groups like Minor Threat, Youth Brigade and Scream, which featured a teenage Dave Grohl on drums.

The group’s live shows were raucous affairs at which H.R. would perform backflips and dive into the audience without warning, whipping the band’s audience into a destructive frenzy that got the group banned from most D.C. venues.

Emigrating to New York in 1981, Bad Brains converted many of the Big Apple’s nascent hardcore bands, including Agnostic Front, Murphy’s Law and the fledgling Beastie Boys.

But Dr. Know’s role wasn’t preordained. Before turning punk on its head as a guitarist, he began his musical journey on the bass. “I had a good friend of mine, back in the day, and he played guitar already, so I started playing the bass,” he recalls.

“But my first bass was actually a guitar – one of those Silvertones from the ’60s where the amp was built into the case. I think it was missing the G string when I got it, so I took off the B and high E as well, and just left the E, A and D. Then after that, I hooked up with some friends of mine and we used to play funk covers. Strictly funk. P-Funk, and stuff like that.”

A musical omnivore, he was also enthralled by the jazz fusion practiced by groups like Chick Corea’s Return to Forever. “I used to play those records over and over and over, and learn the songs by ear by slowing the record down,” he says. “But I also went to see all these people live.

“Literally, I think we were going to a concert every weekend: ‘Oh, Ma. I need $20. I got to go to the concert!’ God bless her. Everything was all mixed together, and we’d see Thin Lizzy and Chaka Khan on the same bill. I saw Return to Forever at a little jazz club in D.C. with Bill Connors on guitar. I saw mister Joe Pass. I was just absorbing.”

Switching to electric guitar, Dr. Know formed Mind Power in 1976 with Jenifer and the two Hudson brothers. The group played jazz-fusion and funk-tinged music and practiced in the basement of a house they all shared.

Darryl bought me an Electro-Harmonix Linear Power Booster that plugged straight into the guitar, and that’s what I used for fuzz

Dr. Know

“I worked at a steakhouse at the time,” he explains. “I got everybody jobs there, except for Earl, and we rented a house from the owner of the restaurant. We used to practice in the basement, and me and Darryl and H.R. would all plug into one padded Kustom amp. Darryl bought me an Electro-Harmonix Linear Power Booster that plugged straight into the guitar, and that’s what I used for fuzz.”

Dr. Know and his bandmates would themselves experience a musical epiphany after being exposed to the bilious aggression of the punk rock music being produced by U.K. bands like the Damned and Sex Pistols, as well as their American counterparts the Ramones and Dead Boys.

“We had started with the fusiony stuff, but when we heard the aggressiveness of punk, that really hit home with us, because we were kids,” he says. “And we decided, We’re going to do this. We started to throw little concerts in our basement. And that’s it. The whole D.C. thing, that’s when it all got started, meeting Henry Rollins [of Black Flag] and Ian MacKaye [of Minor Threat] and playing at this place, Madam’s Organ.”

Because they had already developed their chops playing more intricate material, Bad Brains benefited from a technical proficiency that eluded most of the bands on the then-emerging American hardcore scene.

I was playing all downstrokes, so it had more 'oomph', and I was muting with the right hand, which was something that I got from Al Di Meola

Dr. Know

“We could play. That was the whole thing. Because boys couldn’t play then. Can’t lie about it,” Dr. Know says. “I was playing all downstrokes, so it had more oomph, and I was muting with the right hand, which was something that I got from Al Di Meola,” he continues. “Van Halen had also just come out, and I was intrigued about how he hit the harmonics with the pick. I was like, I’ve got to figure out how to do that. So I did.”

The speed and precision of the Bad Brains’ early performances soon became the stuff of legend, and an album’s worth of demo recordings, later released as the collection Black Dots, swept the punk underground like the furious wildfire that its music evoked.

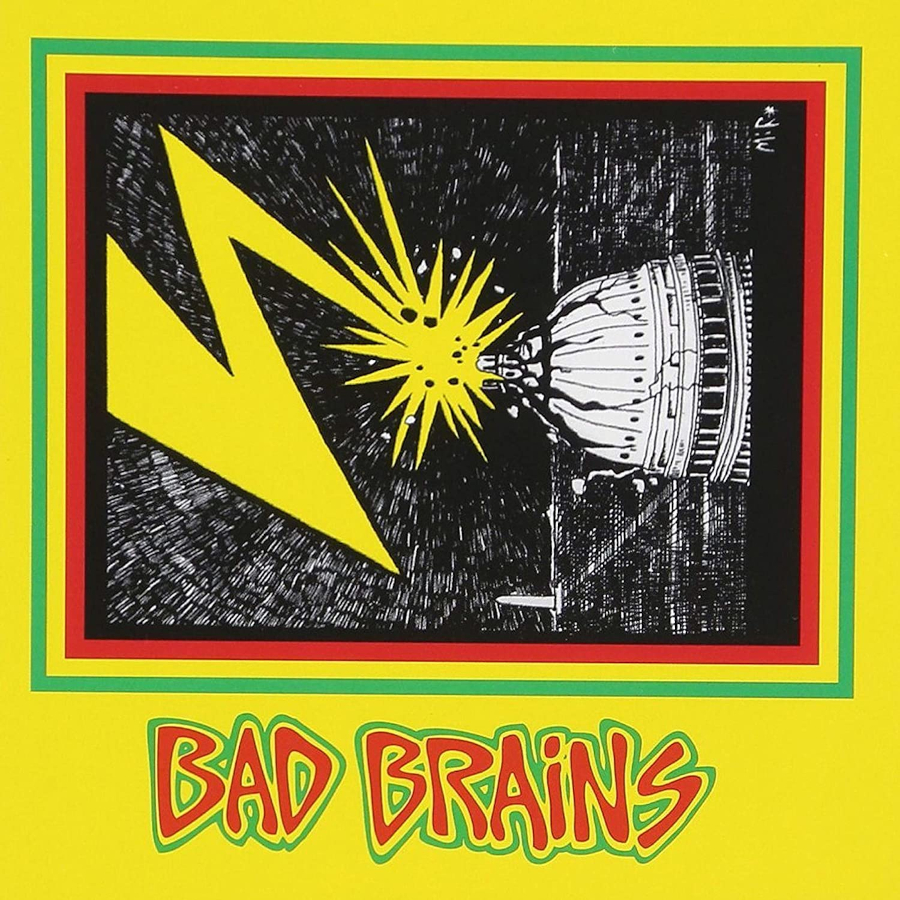

By 1982 when Bad Brains released their self-titled debut, originally issued by the cassette-only ROIR label, it had become de rigueur for other bands in the genre to attempt to match the group’s breakneck tempos.

Everybody was trying to play fast like us, so we had to make it faster

Dr. Know

“Everybody was trying to play fast like us, so we had to make it faster,” Dr. Know explains. But to recognize this landmark album merely for its speed is to do it a great disservice. Recorded in a performance space turned ad-hoc studio on Manhattan’s then incredibly dicey Avenue A in the East Village, classic tracks like “The Regulator” and “Attitude” demonstrated that hardcore could be both aggressive and melodically engaging, and that dismissing the genre as “noise” was done at one’s own peril.

The band, and Dr. Know in particular, were not opposed to referencing their more refined musical past. The album’s opening track, “Sailin’ On,” for example, closes with a ringing major-seven chord. “I love major-seven chords,” he says chuckling. “And then all the different inversions and stuff.”

Along with embracing stratospheric beats-per-minute counts and jazzy tetrads, Bad Brains, who had all adopted Rastafarianism after seeing a Bob Marley and the Wailers concert at Maryland’s Capital Center in 1978, also began to incorporate more reggae into their repertoire.

“I remember going to see Bob Marley because the bass was so heavy at the show,” Dr. Know recalls of the concert. “I was like, Wow, what is going on here? That was it. The music and the message of what Marley was saying and singing had a big influence on us.”

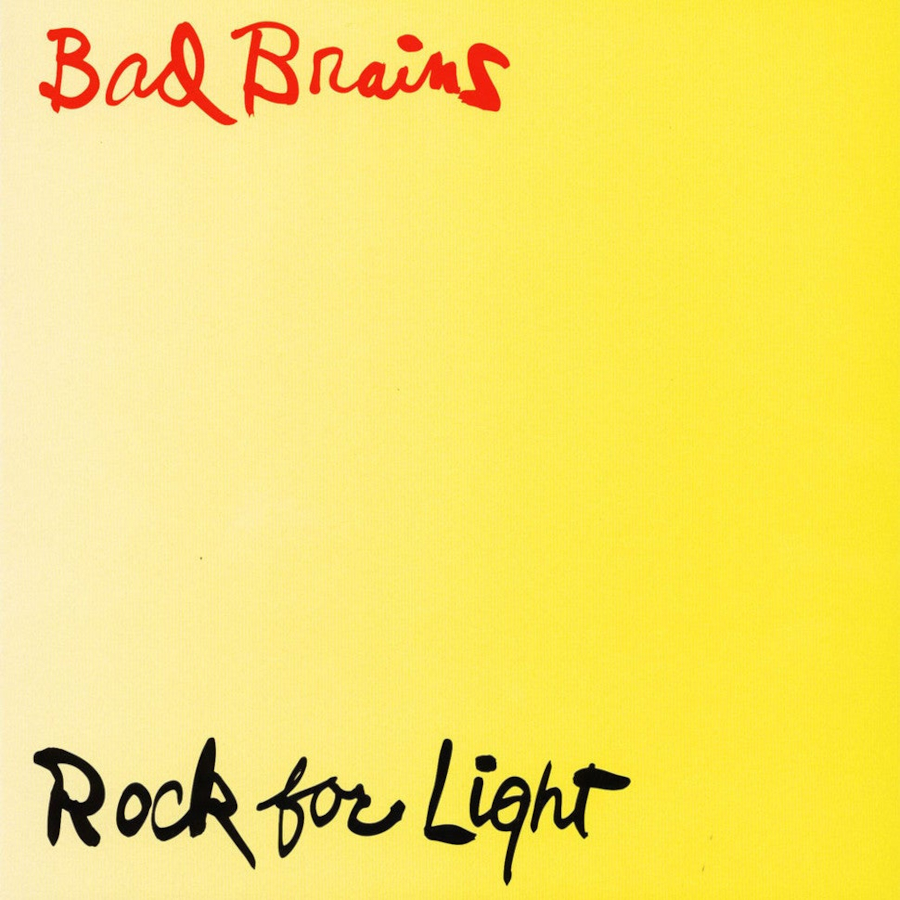

The group’s follow-up to Bad Brains, 1983’s Rock for Light, produced by Cars frontman Ric Ocasek, would further cement the group’s standing as the most dynamic and agile punk band on the planet.

“The beautiful thing about us is that we didn’t have to really follow a format or anything. We just did what we did,” Dr. Know says. “And Ric didn’t try to change us. He just told us to be ourselves and to do what we did best. He died on my birthday. He was a beautiful soul, and I miss him.”

By the mid ’80s, Bad Brains rightfully felt that they had exhausted the possibilities offered by hardcore, and with producer Ron Saint Germain (Mick Jagger, Sonic Youth) behind the board, the group began exploring a more riff-oriented hard-rock direction.

Bad Brains would record two consecutive albums with Saint Germain, 1986’s I Against I and 1989’s Quickness. Although neither release garnered mainstream recognition, both were as original and potent as the group’s earlier, more-frequently referenced work.

As Dr. Know observes, the new direction of these albums was a welcome shift that allowed the group members to employ more of the musical knowledge and know-how they had acquired before diving headfirst into punk rock.

“We just wanted to go back to our roots, play more jazzy kind of stuff,” he says. “Because of our Return to Forever influence – the jazz-rock thing – all the songs have that vibe going, because I was always experimenting with jazz chords and this and that.”

I was always experimenting with jazz chords

Dr. Know

Dr. Know and Jenifer would spend hours musical problem solving to integrate sophisticated chord progressions and voicings into their music.

“Darryl and I, we’d be writing songs, and I’m like, ‘Let me throw this in there.’ But then it sounded good and we had to have a whole transition, a whole chord progression. I would just sit down and figure that stuff out. We’d incorporate all kinds of sixth chords and ii-V-I chord progressions, but we played them with a lot of distortion.”

More harmonically complex, groove- and riff-driven compositions like I Against I’s propulsive “Reignition” and Quickness’s grinding “Soul Craft” also served as a perfect platform for Dr. Know’s uniquely aggressive and often dissonant solos, most of which were performed without the benefit of overdubbed rhythm guitars to support them.

“Part of Darryl’s style on bass is that he plays chords so that we wouldn’t need another guitar player,” he explains. As to how the guitarist determined which scales or modes to play over the band’s often chromatic riffs, he reveals that he mostly left it up to instinct and intuition.

“I would never really think about any of that,” he says. “I would be like, ‘Okay, what key is this in? All right. Roll it!’ And I would just play what I felt. After we finished a record, I would always have to learn what I played, because at the time of recording I would just go and let the spirit make it all happen.”

After we finished a record, I would always have to learn what I played, because at the time of recording I would just go and let the spirit make it all happen

Dr. Know

Ever mercurial and dogged by mental health issues, frontman H.R would leave Bad Brains after Quickness, marking what many consider to be, for lack of a better term, the end of the group’s classic era.

The singer rejoined the group for several more albums in the 1990s and into the new millennium, including 1995’s God of Love for Madonna’s Maverick label (produced again by Ocasek) and Build a Nation, a 2007 effort produced by longtime fan and friend Adam Yauch of the Beastie Boys. But, regrettably, H.R.’s inability to tour for extended periods without incident would prevent the Bad Brains from extensively promoting the releases.

Still, mindful of maintaining their legacy, the group has founded Bad Brains Records and where possible is recovering the rights to their original recordings and remastering and releasing them in restored, deluxe vinyl and digital editions.

For Dr. Know, who suffered some memory loss along with his stroke, the process of revisiting the band’s canon has been both revelatory and comforting. “It’s funny. I was about to say I had to sit down and learn this stuff all over,” says the guitarist, who underwent several years of physical therapy to regain the use of his left hand. “But subconsciously, my hands go right to where they’re supposed to go, and my strength is coming back. I knew I was doing better when I picked up a guitar and bent a string without thinking about it. I was like, Oh shit! I just did that! But I play differently now,” he continues. “It’s not weird, but I know people are going to be like, ‘Damn, man, what are you doing?’ ”

Hopefully, Dr. Know is not overly concerned with having a new voice on the instrument, as his fans have always expected the unexpected from this wildly creative player. And fortunately, it seems that he still has plenty of time left to explore the instrument anew.

“I went and saw all my doctors this month,” he says. “And they were all like, ‘We’ll see you in a year.’ I’m like, ‘What do you mean a year?’ They’re like, ‘You’re good, Doc. Your blood pressure’s all right and your this and your that are all fine.’

“I was like, ‘Really? All right then. See ya!’”

Visit the Bad Brains Records website for a browse through their current catalog.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue

"Get off the stage!" The time Carlos Santana picked a fight with Kiss bassist Gene Simmons and caused one of the guitar world's strangest feuds