Phil Manzanera’s Top Five Career-Defining Tracks

The Roxy Music guitarist picks from a wide range of sessions with a common denominator: Brian Eno

As one of the most influential groups to burst out of England’s early 1970s glam-rock scene, Roxy Music stood head and shoulders above their fellow purveyors of sound. The group began with a musical cocktail that comprised art rock, prog and electronica, all laced with a pop sapidity, before it morphed into a more synth-laden framework.

Roxy influenced a plethora of musicians in their wake and helped cue the new wave synth-pop sounds of the 1980s. At the core of the group’s sound were the offbeat Latino-infused stylings of guitarist Phil Manzanera. His wide-ranging taste for musical diversity was instilled in him by the sounds he heard as child growing up in Cuba.

While it was pivotal to the evolution of Roxy Music’s sound, it also found expression in other projects Manzanera undertook. These included solo outings as well as leading roles in groups such as 801 – where he performed alongside former Roxy Music synthesist Brian Eno – Quiet Sun, and the Explorers, as well as endeavors as a session musician and producer with artists such as Split Enz, John Cale, Nina Hagen and David Gilmour, for whom Manzanera produced 2006’s On an Island and 2015’s Rattle That Lock.

Roxy Music have called it a day on several occasions throughout their long run. The first time was in 1976; they reunited two years later, and again in 1983, before reforming in 2001 and calling it quits yet again in 2011. They regrouped in 2022 to celebrate their 50th anniversary with a tour of North America and the U.K.

“It was a totally spontaneous thing,” Manzanera explains. “I was having a cup of tea with [lead singer] Bryan Ferry around his house in the country last Christmas and he said, ‘Do you fancy doing some gigs to celebrate the band’s 50th?’ And my default position is always, ‘Yeah, let’s go and play!’ So we then got in touch with Andy [Mackay, sax and oboe] and Paul [Thompson, drums], and they also said yes”.

Manzanera’s lifelong passion for guitar playing is evident in his extensive catalog. By any standards, he has been remarkably prolific. “I’ve done about 80 albums in 50 years,” he affirms. “That includes not only mine but also producing and playing on other people’s albums. There are some things I think I did better than others, but you do your best each time.

“My main philosophy of wanting to enjoy guitaring for a whole lifetime has – touch wood – played out quite well. It’s also been a means to meeting people and having fun, and also recognizing the great therapeutic value of music and that you can contribute something to people’s happiness and to your own mental health.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

By coincidence, the tracks selected for Manzanera’s Five Songs entry all feature Brian Eno, who in many instances served as the guitarist’s co-performer by processing his guitar signal through his synthesizer and assisting in performance. “He and I used to do a lot of stuff together where he would treat my guitars through his EMS VCS3 synthesizer, and we both had Revox tape recorders,” Manzanera explains.

“So when you heard us doing stuff together, you’d have heard my guitar signal with echoes and distortion, and stuff like that, but you also would have heard my treated guitar sound through Eno’s oscillators and filters and things. He also had a DeArmond pedal modified to control the speed of our Revox tape recorders.”

1. “In Every Dream Home a Heartache” by Roxy Music from ‘For Your Pleasure' (1973)

“We played this track on the recent Roxy Music 50th anniversary tour of America and it went down incredibly well everywhere. And one of the reasons for that is that it meanders along for quite a long time in a quiet sort of way and then explodes when my guitar comes in. It was one of the best moments I ever had playing guitar.

Most of the time I was serving the song, but on this track I had freedom to play a solo

Phil Manzanera

“On the recorded version, the guitar has treatments by Eno but not as much as usual. There is also some tape flanging. And our producer, Chris Thomas, had been [producer] George Martin’s assistant, so we benefited from the legacy of the Abbey Road school of recording with the Beatles, because we had Chris there at the helm during our recording sessions.

“On the album version, the end guitar solo is not incredibly long, because in those days, to get the best sound onto vinyl, you needed it to be 20 minutes of music on each side. But we did record a full version, which had a much longer solo.

“Most of the time I was serving the song, but on this track I had freedom to play a solo. I used a borrowed black 1957 Les Paul, which I ended up playing for the next 15 years before the guy who owned it asked for it back. I was devastated. But in 2000, the Gibson Custom Shop made me a version of that guitar, and it is terrific.”

2. “Amazona” by Roxy Music from ‘Stranded’ (1973)

“Nineteen-seventy-three was the last year with Brian Eno in Roxy. Once he had left, I didn’t have anybody to treat my guitars, so I had to do it myself. I got in touch with the guy who made the original VCS3 synth, Peter Zinovieff, and asked if he could make me a version where you could control lots of aspects of it yourself by using the DeArmond pedals, which would go up and down and sideways so that way you could use the different functions on the VCS3.

I got in touch with the guy who made the original VCS3 synth, Peter Zinovieff, and asked if he could make me a version where you could control lots of aspects of it yourself by using the DeArmond pedals

Phil Manzanera

“By time we got to the album Stranded, it was the first time that Andy and I started contributing songs and material to the Roxy canon. I said to Bryan, ‘I’ve got this riff and this other bit, but it’s in 7/8.’ This is the only time in any Roxy song where there is a different time signature. That comes from obviously the kind of music that I was playing before with Quiet Sun, stuff which was all different time signatures and a bit proggy. So Bryan took on the challenge, and the whole song was built around that riff.

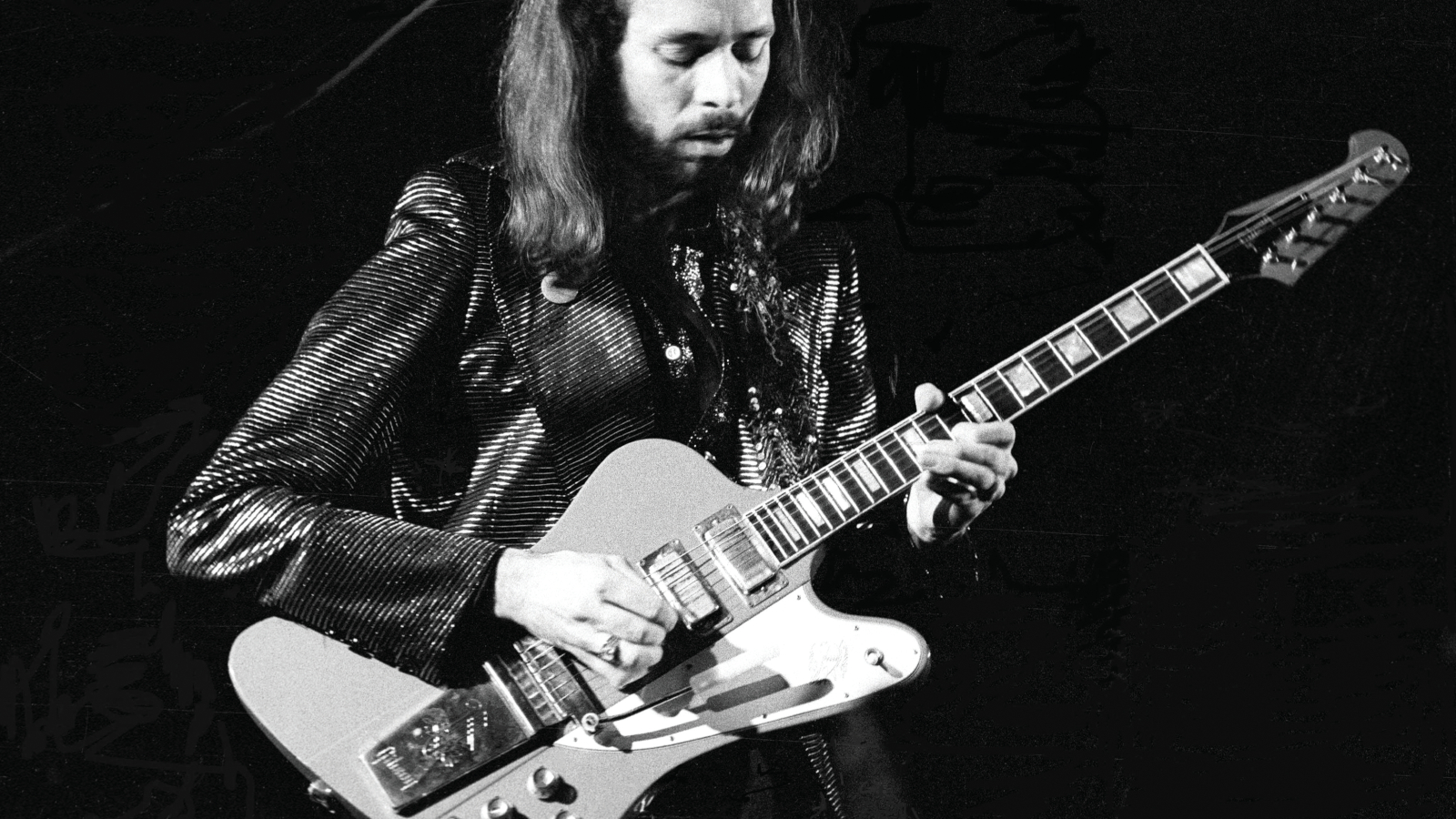

“When it came to recording, I played the riff using my red [reverse] 1964 Gibson Firebird and this new module, the guitar version of the VCS3, and my Revox. On the recording, you can hear what happened when I plugged it all in; the thing worked properly for about three times only, and one of those three times was what was recorded. But it has this unique sound, which I never achieved again, and nobody anywhere has ever been able to achieve again. It sounds like the guitar is underwater, and that has to do with the filtering.”

3. “Needles in the Camel’s Eye” by Brian Eno from ‘Here Come the Warm Jets’ (1974)

“Eno had left Roxy by this point, but as I was sharing an apartment with him and we were great friends, we continued working together. I was recording Stranded with Roxy at Air Studios every day between 12 to 6 in the evening, and afterward I would get on the underground and go to the studio on the other side of town to work on Eno’s first album. This was the first song on the album, and we wrote it on my mother’s piano in her front room where I used to live with her. We just sat there going jing, jing, jing.

On the recording, I played a white Strat that Eno got from his milkman for £30 because on the back of it was written, ‘J H Experience’

Phil Manzanera

“The recording is quite funny as it’s got a weird guitar sound, which came from me strumming away while Eno played the guitar’s whammy bar. It was like a two-man operation to create that sound. You could probably do that with some weird pedal now, but in those days, everything was what they called Heath Robinson: You just had to make it up. For example, if you wanted some weird sounds, you would stick some screws into a piano. And that’s how everything was made up on the spot. I just love that sound; it’s great. Eno was and is very engaging and always wanting to try something different, and that’s because of his art school background and the way he was taught, which was to be much more experimental. Mind you, he had the same art teachers as Pete Townshend.

“So on one hand here I was with Roxy learning the craft of the Beatles and all, while on the other hand, down at the other studio with Eno, it’s like anything goes, where we were trying everything that really was mad and weird. During the period between 1971 to 1976, I spent a lot of time with Eno doing albums and stuff, and we also had the 801 band together before he went off to work with Bowie [on his Berlin trilogy].

“This song has been used in films and seems to be quite popular. On the recording, I played a white Strat that Eno got from his milkman for £30 because on the back of it was written, ‘J H Experience,’ which we believed meant it was once owned by Hendrix. Then Eno sold it to me for £60!”

4. “Gun” by John Cale from ‘Fear’ (1974)

“John Cale and the Velvet Underground were always big heroes to me and Eno, and to everyone in Roxy Music. I guess they were the epitome of art rock in some ways, with being associated with Andy Warhol and that sort of thing. But once John left the band, he ended up being an A&R guy at Warner Bros. in L.A. We had asked him to produce our second album, but he suggested Chris Thomas to us, who had produced his album [1973’s Paris 1919]. Then a guy at Island Records, Richard Williams, said John was coming to London to record, and would I co-produce it with him? Both Eno and I are credited as executive producers, but today we’d be actual co-producers.

I went in and played some mad stuff on my red Firebird and Eno treated it, and when John came back, he sort of said, ‘Wow, what the hell is that? It’s brilliant!’

Phil Manzanera

“So I found him a band and got the studios organized and ended doing a lot of stuff. Then John got quite busy doing other things and wasn’t at the studio a lot. I was getting a bit bored, so I rang Eno and asked if he would come down so we could just play stuff and see whether John would like it.

"And on this track, I was trying to pretend I was in the Velvet Underground and playing a solo like you could hear on the first Velvet Underground album [1967’s The Velvet Underground & Nico]. The difference, however, was that Eno treated my guitar with his VCS3 synthesizer, just as he had in Roxy Music. I went in and played some mad stuff on my red Firebird and Eno treated it, and when John came back, he sort of said, ‘Wow, what the hell is that? It’s brilliant!’

“It’s incredibly long, but in the context of what was happening in 1974 and the other music at the time, it was quite different to have that in there. It was a crazy, mad type of playing that I just continued to love to do, especially with Eno. I did some of that crazy stuff on his solo albums as well.”

5. “Diamond Head” by Phil Manzanera from ‘Diamond Head’ (1974)

“After working on Eno’s solo stuff, and on Bryan Ferry’s and Andy Mackay’s too, I asked management if I could do a solo album. It was just an excuse to get my mates in, such as Robert Wyatt, John Wetton and the guys from Roxy.

“I had this more melodic kind of song, and I was trying to decide whether to make it into an instrumental or a song with lyrics. But since I already had a lot of songs, I chose to do an instrumental. It’s basically the Roxy guys on it: Paul Thompson playing drums; Eddie Jobson, who’d joined Roxy to replace Eno, played the string and piano parts, and John Wetton was on bass.

I always wanted my guitar to sound almost like an organ, with the distortion

Phil Manzanera

“I always wanted my guitar to sound almost like an organ, with the distortion. I remember wanting it to sound like the fuzzed organ playing of Mike Ratledge of Soft Machine, but also like Randy California and the band Spirit, who had this beautiful smooth tone on some of their tracks. The guitar I used on this was a 1965 red non-reverse Gibson Firebird, which I had bought in 1974. And again, I got Eno to treat it through the VCS3 with a bit of filtering as well, which gave it a little bit of an extra edge. In those days all you could buy was a cheap Fuzz Face pedal and have tape echo from the Revox, which we also used on this.

“It’s called ‘Diamond Head’ because I was born in London but brought up in Cuba during the revolution and had to leave afterward. We went to Hawaii, and Diamond Head is the mountain at the end of Waikiki Beach. So it was autobiographical for me to name it after that place.

“The track has a slow drift and is very melodic. I can imagine sitting on the beach with the wind going through the palm trees. I also played it live on the 1975 Roxy tour and then played it with 801 and many other times too all over the world over the years.”

Joe Matera is an Italian-Australian guitarist and music journalist who has spent the past two decades interviewing a who's who of the rock and metal world and written for Guitar World, Total Guitar, Rolling Stone, Goldmine, Sound On Sound, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer and many others. He is also a recording and performing musician and solo artist who has toured Europe on a regular basis and released several well-received albums including instrumental guitar rock outings through various European labels. Roxy Music's Phil Manzanera has called him "a great guitarist who knows what an electric guitar should sound like and plays a fluid pleasing style of rock." He's the author of two books, Backstage Pass; The Grit and the Glamour and Louder Than Words: Beyond the Backstage Pass.