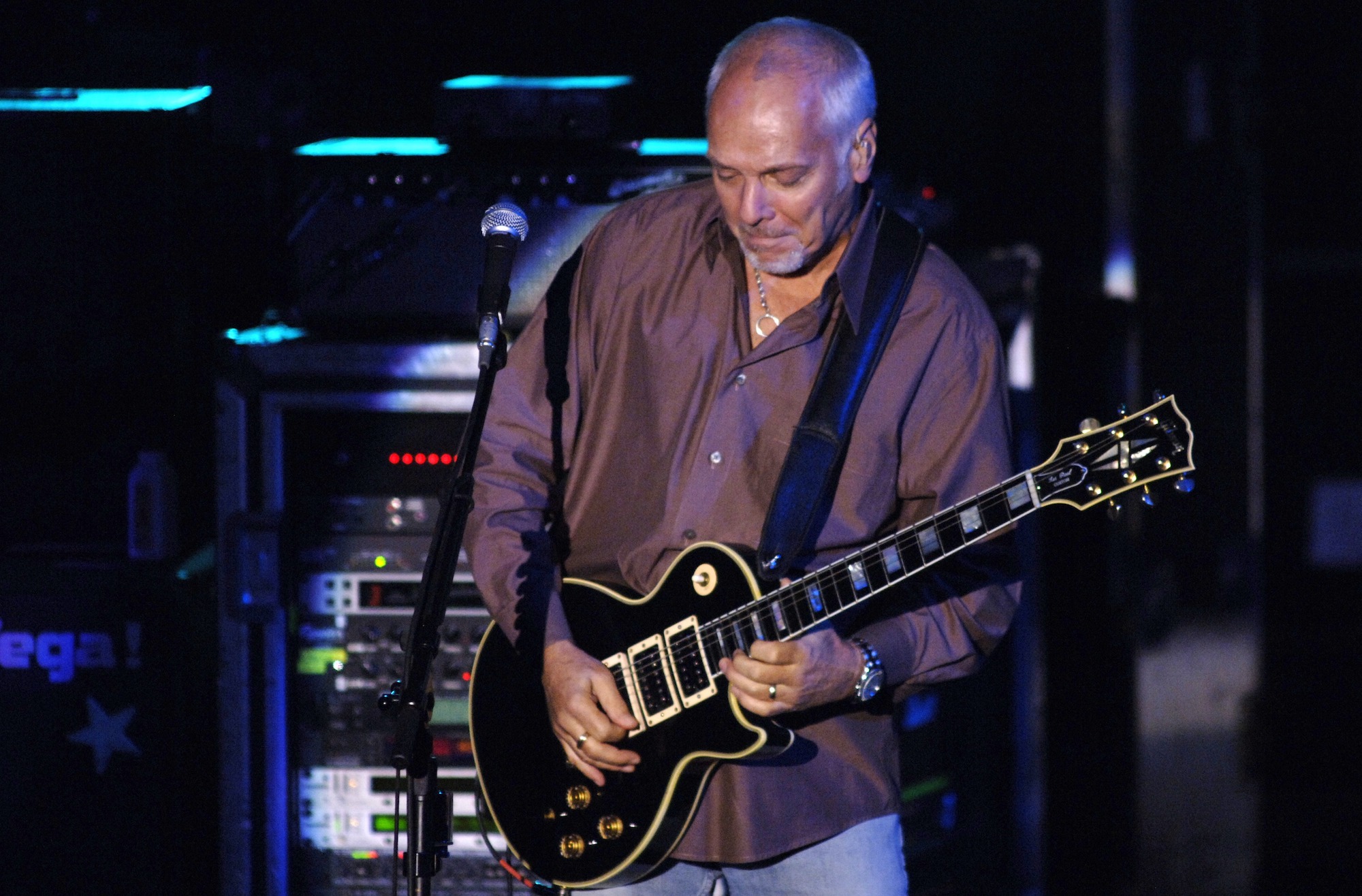

“George used to have acoustics all over his house in various tunings – I’d pick them up and say, ‘What the hell is this?,’ then get out my cigarette pack and write down the tuning”: Peter Frampton on lessons learned from George Harrison and Steve Marriott

Armed with a “million-dollar Marshall,” Frampton took cues from Hank Marvin and Django Reinhardt for his stellar 2010 effort, Thank You Mr. Churchill. That same year, he spoke with GP about the album's genesis, and gear revelations

Peter Frampton said that he felt “validated” as a musician after his Fingerprints album won the Grammy Award for Best Pop Instrumental Album in 2007 – a sentiment that some might find surprising.

After all, Frampton had achieved fame with Herd at 16, co-founded Humble Pie with Steve Marriott two years later (recording five albums, including the legendary Performance Rockin’ the Fillmore), recorded with luminaries such as Bill Wyman and George Harrison, and released the astronomically successful Frampton Comes Alive! in 1976. But Frampton had come to feel that after appearing shirtless on the cover of Rolling Stone, and as Billy Shears in the ill-fated film Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band, attention had been diverted away from his abilities as a serious guitarist and songwriter.

Reinvigorated by his Grammy win, Frampton chose to follow Fingerprints with the hard-rocking Thank You Mr. Churchill, a highly personal album replete with strong songwriting, imaginative riffs and solos, and some of his best guitar tones ever.

“I wanted to reintroduce my singing voice on this one and do something completely different than Fingerprints, even though I did maintain a connection by including two instrumentals,” explains Frampton. “That said, I never really sit down to write anything in a specific direction. Whether I’m writing alone or with others, what happens just happens, and then at some point in the process I get a sense of what an album is going to be as a whole.”

There are lots of outstanding tones on the new record, particularly huge crunch and distortion sounds. Did you have a basic setup or did it vary from song to song?

“It varied, but I got most of the sounds – especially the lead sounds – with one of two Marshall amps. I used a ’70s Marshall that was modified by Jose Arredondo, the guy who modified Eddie Van Halen’s amps, and a 1962 JTM-45, which I called ‘the million-dollar Marshall’ when I bought it, and now its worth even more [laughs]. I often just played straight through the amps, though sometimes I boosted the gain with either my Klon Centaur or Fulltone OCD pedals. I experimented with lots of different pedals this time.”

I was going for sounds that were a little more angular, ugly, and ferocious on this album

What are a few examples?

“I had never used a DigiTech Whammy before – I’m a late bloomer – and I love that pedal. I also really like the stuttering sound that Tom Morello gets by flicking the pickup selector switch on his guitar, and I used a Gig-FX Chopper to get a similar effect on Asleep at the Wheel.”

Is that the Whammy on the solo on Solution?

“No, that’s actually a Foxx Tone Machine. I have a couple of the real old ones, but that was a new one they gave me because they know that I’m a Foxx Tone guy. There’s nothing like that effect. I did use the Whammy to add a high octave to the solo tone on I Want It Back, however, though it doesn’t stick out as much as with the Foxx. It added great top without being too treble-y, and a bit more ferociousness. I was going for sounds that were a little more angular, ugly, and ferocious on this album.”

Suite Liberté begins with a sort of Hank Marvin by way of Jeff Beck sound and feel. Was that intentional?

“Well, the Hank Marvin part was very intentional, because having played with him on Fingerprints and with the Shadows, I had tried his Strat – or rather I was allowed to play it [laughs] – and I found out how to go about getting one.

“I started playing as a kid because of Hank, and I’ve always wanted a guitar just like his. Mark Kendrick at the Fender Custom Shop in California made me a Hank Marvin model, and then Mark Pressling in the Fender Custom Shop in England, who tailors guitars to Hank’s specifications, worked on the neck.

“There’s also the VML Easy-Mute tremolo unit made in England by Ian St. John-White, on which the bar is at a 90-degree angle so that you can mute the strings and hold the bar at the same time, which I guess is something that Hank wanted. Then, on the same day that the guitar arrived, I also got the Alesis Echoes From the Past effects unit, which has echo presets named after Shadows songs.

“I plugged the guitar and the Alesis into a ’59 Fender Deluxe and spontaneously recorded what became the intro to Suite Liberté – so it was absolutely inspired by Hank Marvin. And when you’re playing a Strat you obviously think of Jeff, as well, and the combination of those two is pretty powerful stuff.”

You transition out of that section using a fat, bluesy tone. What’s happening there?

“That’s my Gibson 1960 Les Paul reissue aged by Tom Murphy. I plugged it straight into the JTM-45 and went for a Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton sort of tone. I came pretty close, except that I added a little more room ambience to get that everybody-playing-around-one-microphone old-school blues sound.”

There’s a sort of manic, maniacal acoustic groove thing happening on Restraint. Was that played in an altered tuning?

“The first and sixth strings were tuned down to D, which enabled me to play mostly normal fingerings while at the same time creating an ominous dissonance that lent itself to the theme of the song, namely the greedy pigs on Wall Street.”

The huge tones you got on Performance Rockin’ the Fillmore came from plugging a Les Paul into a Marshall though, right?

“That was it. The only trick I used was that I would plug into the high-gain input [input 1] of the second channel – the bassier one – and then patch the other input from that channel to the high-gain input of the first, or more trebly, channel. I’d just bring in a little of the brighter tone by turning that channel up to about one quarter, while adjusting the tone controls for the second channel. I believe that’s the opposite of how most people did it.”

Speaking of Humble Pie, what was the most significant thing you took away from your years playing with Steve Marriott?

“The riff! Steve was the riffmeister. He taught me a lot about how you attack a note or a chord – he was very precise – and also about how long to hold each note or chord and the space that you leave in between them. Those things are as important as the notes and chords themselves.

“Steve was also a really good orchestrator of big guitar riffs. I would write big riffs, too, based on what he had taught me, and then we would combine them into these enormous arrangements. And although Steve was very blues oriented, he also had a great melodic sense. Like on the track Black Dog, where he came up with a really beautiful melody that I just harmonized with. He was a much broader musician and writer and singer than I think he even knew himself.”

You also worked with George Harrison. In what ways did his guitar playing influence what you do?

“I definitely stole a couple of tunings from him [laughs]. He used to have acoustic guitars all over his house that were tuned in various ways and I’d pick them up and say, ‘What the hell is this?’ and then get out my cigarette pack and write down the tuning. I hadn’t really experimented with alternative tunings before that, and he definitely pushed me in that direction. And obviously his slide playing influenced me. The lead riff on Something’s Happening is sort of Harrisonesque.”

Do you remember any of those tunings you wrote on cigarette packs?

“The tuning that I remember the most is one that I used myself on Wind of Change. The low E and A strings drop down to D, the fourth string remains unchanged, the third string goes up to A, the second string up to D, and the first string up to F#, so there’s a D triad on top and three Ds on the bottom. It’s a very strange tuning, but oh my God, it sounds huge.”

Django Reinhardt was a big influence on you early on, and you recorded a gypsy jazz-style tune with John Jorgenson on your last album. How would you say your interest in Django is reflected in your playing?

“The piece I recorded with John, Memories of Our Fathers, is clearly in that style, but I think the way that Django used diminished runs, for example, is something that is visited on the current album as well as when I play live.

“Listening to Django all the time has also influenced the way that I attack notes, which is a hugely important part of the sound. And Django was an incredibly melodic player who could obviously play a string of notes from one end of the fretboard to the other in a half second, but also knock you out just by playing a single note across six chord changes. In other words, he didn’t play fast all the time just because he could.”

- This interview with Peter Frampton was originally published in the July 2010 issue of Guitar Player.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!