Pete Townshend on the Genesis of His Pop-Art Masterpiece, 'The Who Sell Out'

How an accidental concept album captured the pop culture zeitgeist and found a band stretching their wings creatively.

In the world of rock and pop, the Who have always been, and will likely remain, the kings of the concept album. But while 1969’s Tommy is their most famous, 1971’s aborted Lifehouse their most troubled, and 1973’s Quadrophenia their most ambitious, they were all preceded by an oddity known as The Who Sell Out.

Released in 1967, the Who’s third full-length record stands as their first official concept album. Which is odd, considering that, for the most part, it’s no such thing at all.

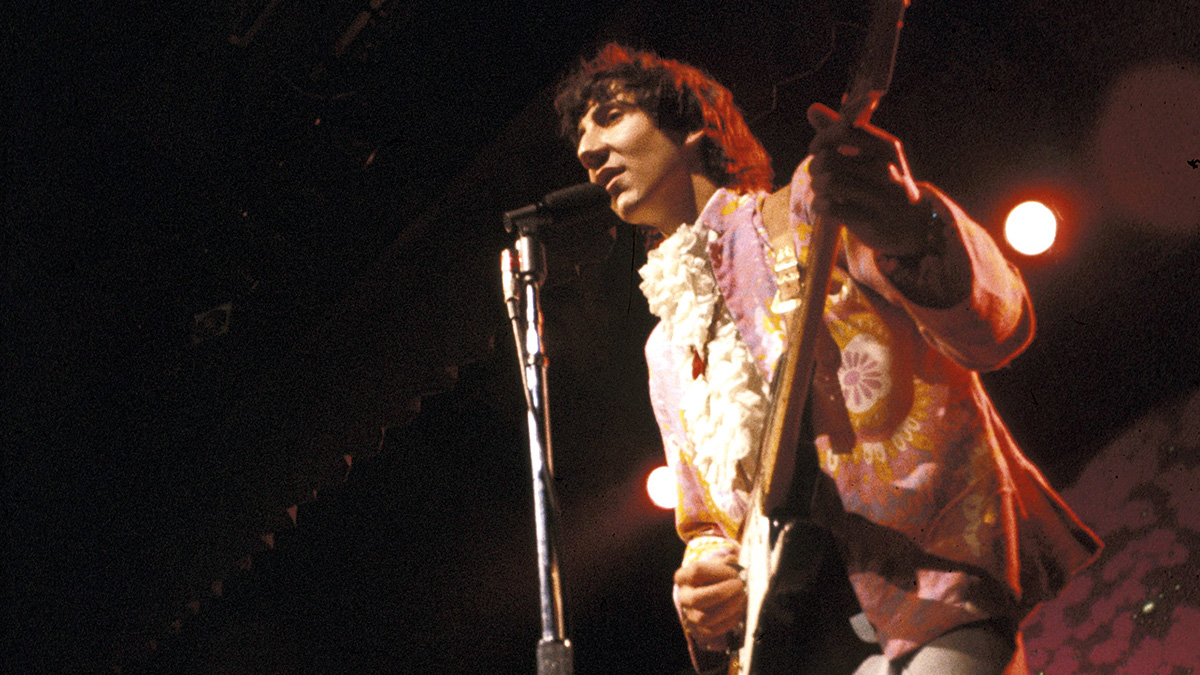

“It didn’t have much of an aim or a theme or a direction,” Who guitarist, primary songwriter, sometime lead singer, and overall visionary Pete Townshend admits to Guitar Player. “It was cobbled together very much in the last minute.”

The notion in pop music was that everything was going to be so brief. We never realized that this music would still be around 50 or 60 years later.

And yet, it’s also a triumph of creation in every way – an ambitious step forward for a band that had already moved beyond their early status as a U.K. hit-single machine via the likes of “I Can’t Explain,” “My Generation,” “Substitute,” and other three-minute power-pop gems.

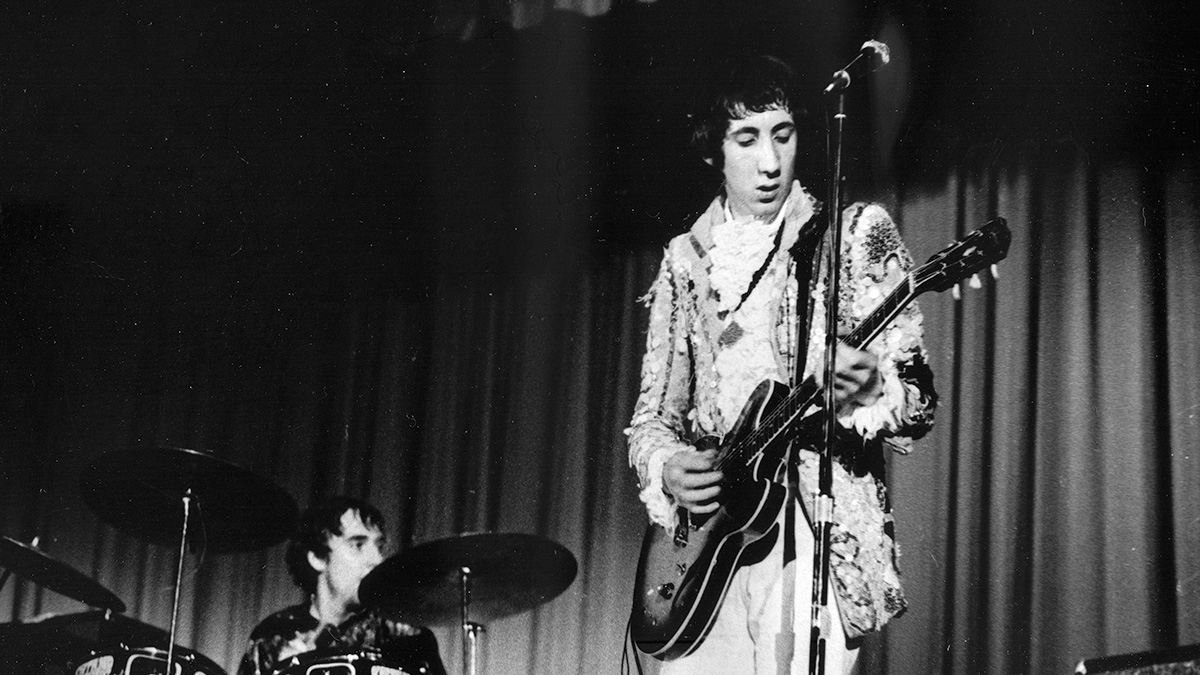

By 1966, Townshend had composed the “mini opera” “A Quick One, While He’s Away,” and the music he had on deck for The Who Sell Out included the multi-part “Rael,” the psychedelic-pop masterpiece “I Can See for Miles,” and the coming-of-age tale “Tattoo.”

The songs themselves were disparate and unrelated, with the ultimate concept – interspersing the compositions with jingles and commercials that imitated a pirate radio broadcast – being tacked on very much at the end of the process.

So too was the album’s pop-art cover, which, in a satirical extension of the album title and audio advertisements, presented the band’s members shilling for various products – Townshend applying Odorono deodorant to an underarm, singer Roger Daltrey immersed in a tub of Heinz baked beans, bassist John Entwistle as an acolyte of bodybuilder and exercise guru Charles Atlas, and drummer Keith Moon squeezing Medac zit cream onto his cheek.

It’s an “out-there” idea, to be sure. But what resulted was a triumph of sound and style, a record that, like the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds and the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, captured the zeitgeist of the bold musical moment while propelling rock and roll music forward into previously unexplored territory.

Now this groundbreaking effort has been revisited by Townshend in a massive new set. The Who Sell Out Super Deluxe edition is packed with more than 100 tracks, 46 of which are unreleased, as well as posters, concert programs, flyers, and other memorabilia, plus an 80-page hardback book with rare photos, artifacts, track-by-track annotation, and sleeve notes from Townshend and others who were involved in the process, including studio engineers and album art designers.

It’s the most comprehensive look to date at an album that stands not only as a pivotal moment in the Who’s career – it served as something of a bridge between “A Quick One, While He’s Away” and Tommy, the conceptual milestone that would follow quickly on the heels of The Who Sell Out – but also a transitional moment in all of rock and pop, when individual singles began to be supplanted by albums.

Townshend sat down with Guitar Player to discuss the making of the landmark album and the inspired cultural and personal moment that birthed it – even if, as he readily admits, he never expected it would be something still worth talking about.

“At the time, there was this idea that there was a need to create these new things, and that we needed to create them very, very quickly,” he says. “Because the notion in pop music was that everything was going to be so brief. We never realized that this music would still be around 50 or 60 years later.”

The Who Sell Out has been issued in various deluxe forms over the years but never in a set this expansive. Was there anything that came to light this time that was particularly eye opening to you?

You know, that’s an interesting question. I probably don’t have as much to do with any of these box sets as you would imagine, but with this one I very much enjoyed digging back into the demos that I did and making sure that they held up.

And I also made a few discoveries, particularly with some of the information in the included essays. For example, the story from Chris Huston [recording engineer at Trackmasters Studio in New York City, where some sessions for The Who Sell Out took place]: I didn’t know that he’d managed to reconstruct parts of the “Rael” track he lost from a mono cassette that he’d made. So there’s been a few surprises like that.

You mention digging back through the demos, and to be sure, there are tons of great ones included on this set. One that I would highlight is your “I Can See for Miles” demo, if only because the finished version on The Who Sell Out that we all know and love is such a dramatic production.

But what’s interesting is you hear all that drama, as well as the imaginative instrumentation and arrangement, even in your home demo. It’s a rather complete thought, even that early on in your career as a songwriter and artist.

The demo process for me was a recording process, which was about as good as I could get with equipment at home at the time. As time passed, my home studio equipment got better and better, until, in some ways, it was better than some of the studios that we worked in. [laughs]

Brian Wilson had a harmonic sensibility that was sort of off the map. “God Only Knows” is a masterpiece

But around this time, I was working with two semi-pro Revox tape machines, bouncing backwards and forwards. And so I was getting good-quality recordings and spending a lot of time doing them.

I was doing it really for amusement and as a way of passing the time, to be honest, until I met the woman that was going to be my wife, Karen Astley, and I started to spend a lot of time with her.

But until then, I was living in a flat on my own. The band would do a show, mainly in Scandinavia or Germany or France or in the U.K. somewhere, and then we’d get back home and I’d be on my own a lot at the time. So my time was spent making demos. And I think you can see from this collection of stuff, there’s a broad range of things going on. I was experimenting.

To your point about experimentation, people look back on this time period in the late ’60s as a golden age of rock and roll, when new and adventurous and creative sounds were being forged. But it was also a golden age of pop. The Who Sell Out is a great example of this, not just in the music but also in the packaging and in the commentary.

I think that’s right. You know, if we think about ’66 as being the year that we got Pet Sounds from the Beach Boys, that was a quantum leap for them, from being kind of a surf band very much in the tradition of Jan and Dean, which was very lighthearted, very much about the beach, very much the California story. It was, “Push away our blues!”

And mind you, Brian Wilson had a harmonic sensibility that was sort of off the map. “God Only Knows” is a masterpiece. And I suppose to some extent with “I Can See for Miles,” the challenge was not to try to equal Brian Wilson’s harmonic sensibility but certainly to say, “Well, that’s a new standard. Instead of just doing three-part harmony, let’s do five-part harmony and see what happens.”

The problem for me as a guitar player was that, because of Keith Moon’s style, I had to really be the metronomic beat in the band... There had to be a heavy riff from me in order for the band to hold together

The other thing that happened around that time was, of course, the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s, in ’67. And although we had been doing our own experimentations – we had done the “A Quick One, While He’s Away” mini-opera – I thought that at least half of this record would be my first real opera, “Rael.” And that got condensed down to a six- or seven-minute piece. I can’t remember – it’s bloody short. But the point is, we were all trying new things.

So it was a very interesting period. And I think the other thing that was interesting was the amount of conversation that flowed back and forth in those years. I’d be hanging out with people like [Rolling Stones guitarist] Brian Jones or, to a lesser extent, Paul McCartney. And Paul was always incredibly supportive of my experiments as a writer for the Who.

He really liked the mini-opera and told me so when we met one time in a club. And he really liked “Happy Jack,” which was a complete kind of nonsense song, in a sense. But he got the idea that I was writing a song about mental illness, at a time when that was not a subject for anything, let alone pop music.

You’ve been outspoken in the past about the fact that, around this time, you became enamored with Jimi Hendrix, who was just starting to explode on the scene.

The impact of Hendrix’s playing isn’t always front and center in your own work, but we do hear it come to the fore in some of the rare tracks here, in particular the non-album instrumental “Sodding About,” which has some really wild guitar sounds.

You know, I actually haven’t listened to that track. I’ve heard that about it, too, so I really need to listen to it, because I don’t remember it! [laughs] But I was so impressed and blown away by Jimi, because the single-note shredders of that period like Eric [Clapton] and Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck – particularly Jeff Beck – it seemed to me that they didn’t know how to play rhythm.

They could play great solos, and they were, as I said, the original shredders. But when Jimi appeared, he was playing a sound that was full, and with a lot of two-note and three-note and four-note chords. And then his solo playing, it was kind of ascendant. And so for me, he was a really interesting model.

But the problem for me as a guitar player was that, because of Keith Moon’s style, I had to really be the metronomic beat in the band. So when I tried to play solos, it was usually when I had stopped the band, and I would just noodle around on my own for a while and then get into a heavy riff. There had to be a heavy riff from me in order for the band to hold together.

You had a bit of a different job, so to speak.

Well, I think the other thing is that I didn’t practice guitar; I just made demos. I came home and I recorded. You know how they say you need 10,000 hours? 10,000 hours to learn how to play any decent sport. 10,000 hours to get even basically proficient on an instrument. I probably still haven’t done 10,000 hours on guitar.

I think there’s a sense that we’re losing the idea that the guitar is something you can just pick up and strum away on and find solace and amusement and connection with it creatively

I still don’t practice. I take terrible risks onstage with electric guitar and when I’m playing solos. I just let my fingers do stuff. And sometimes there are glorious bum notes, and sometimes there are terrible bum notes. But I don’t practice. And yet, I do know quite a bit about music theory; it just doesn’t fall under my fingers.

So as a guitar player, I’ve always felt that it was important for me to be able to use the instrument as an inspirational tool. And I think it might be that we’re sort of losing that now, with the obsession on Instagram with really extraordinary shredders.

You know, they’re playing at astonishing speeds, and playing beautifully, but I think there’s a sense that we’re losing the idea that the guitar is something you can just pick up and strum away on and find solace and amusement and connection with it creatively.

You touched on this earlier, but one thing that is interesting about The Who Sell Out is that, while it’s considered to be one of the first concept records, from a song perspective there’s no real concept. To the contrary, the concept was engineered in order to help tie together what is actually a rather disparate collection of tunes.

That’s correct. This might be true for a lot of artists, because, in a sense, the songs aren’t always the complete story, are they? If we think of Sgt. Pepper’s as a concept album, or even Pet Sounds as a concept album, it’s a concept of style and a concept of assembly and a concept of approach and a concept of packaging.

By the time we got to Tommy, we were very much aware, possibly because of The Who Sell Out, that the packaging had to be as impressive as the music, or at least as extensive. And so you’re absolutely right.

In my essay for The Who Sell Out set, I talk about going to get my photograph taken for the album, and that was the first time I heard the title. I can’t remember what it was going to be called before that – it was something else, not a very good title. But I heard the name and I just thought it was inspired.

And, of course, from that point on, you really did dive deep into the concept-album waters.

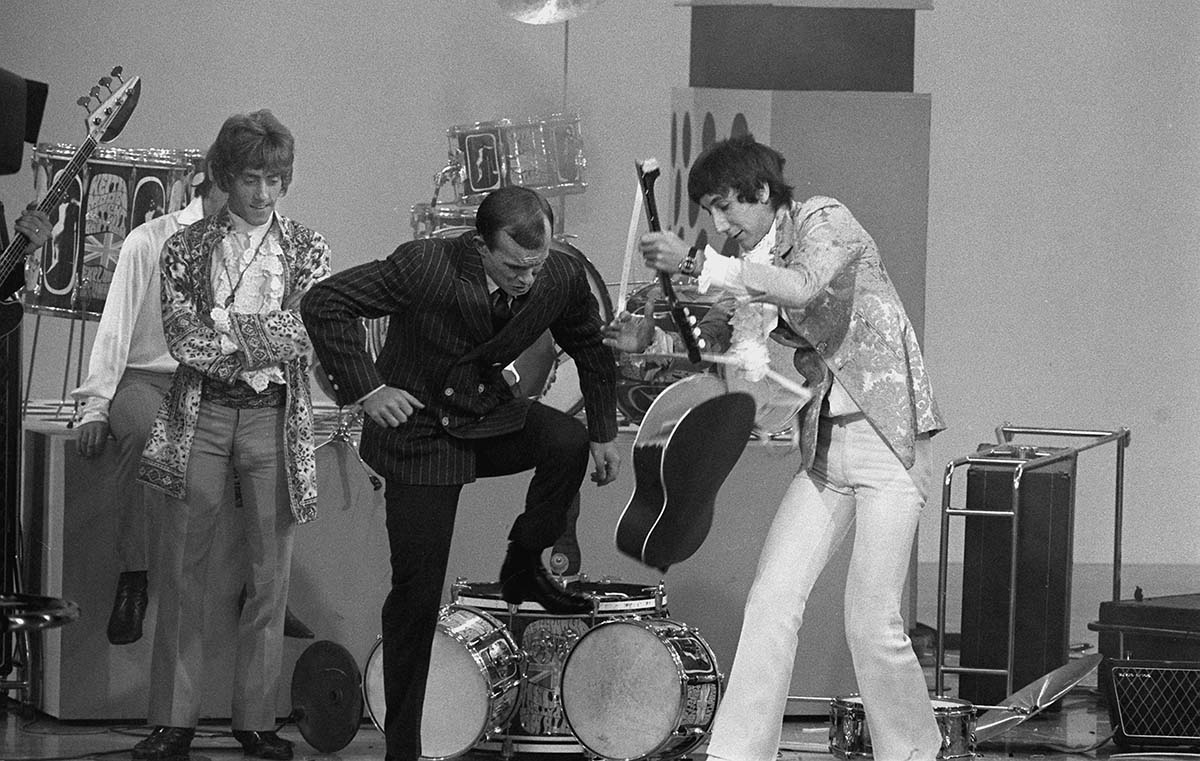

Well, the reason why perhaps we were nailed for this concept thing is because it did start right at the beginning – the association with the mod movement, the association with using feedback and knocking the instruments around, the complete focus on a male audience rather than, you know, the teeny-bopper screaming audiences that followed the Stones and the Beatles.

We walked into the pop industry looking like a bunch of people that had attitude, that had ideas, that had thoughts

We were just kind of dissing them completely, like, “We’re not going to perform for you – we’re going to write for you.” Then with the way we started to work with pop-art imagery, which in a sense went on to define the whole American idea of what Carnaby Street was about, the whole “Swinging London” thing – we were right on the button.

So in a way, from the very beginning, we walked into the pop industry looking like a bunch of people that had attitude, that had ideas, that had thoughts. A lot of it was borrowed, and a lot of it was reflected, but it appeared to be incredibly cohesive.

And I think without our managers, without Chris Stamp and Kit Lambert, in a very short period of time I would have been told to shut the fuck up – particularly by Roger Daltrey. But when it was clear that it was working, we stuck with it. And so even to this day, whenever I ring Roger up and I say, you know, “Shall we try to make another record?,” he says, “You’ve got another bloody concept?”

Maybe he’s just concerned he’s going to have to climb into another bathtub filled with baked beans.

[laughs] I think also he doesn’t really want to be selling ideas that either are vague or evolving, that are unfinished. But I’m still at a place now where I want to be gambling and taking chances as a studio composer and writer.

Since you say you’re still a gambling man when it comes to the studio, is there any chance there might be more new Who music on the horizon?

It could be tricky. And I think it’s partly because we’re getting older, and partly because this lockdown has left us flailing quite a bit. I think Roger just wants to get out and use his voice. And so it feels to me like what he’ll want to do is play catch-up with touring, which is very much what we did after I took a great long sabbatical from the Who from the end of ’82 right through to ’96, pretty much.

I think Roger just wants to get out and use his voice. And so it feels to me like what he’ll want to do is play catch-up with touring

But I don’t know the extent to which I will be willing to tour the way we have been touring in recent years, although I have been finding it easy and I’ve been finding it interesting.

As far as a new record, it does take quite a lot of time to put together the 20 or 30 songs that are needed for both Roger and I and any producer that we might be working with to cherry-pick the ones that fit the times. Because you write the songs, and then two years later you’re putting them all out, and you just hope that you’re going to hit the mood of the moment.

A lot of artists are now writing songs at home, recording them at home and putting them out within weeks. But our process is the old-fashioned way, and it does take a long time. So I don’t know, but I am optimistic. And I’m certainly full of ideas.

- The Who Sell Out Super Deluxe edition is out now via Geffen.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.

"This 'Bohemian Rhapsody' will be hard to beat in the years to come! I'm awestruck.” Brian May makes a surprise appearance at Coachella to perform Queen's hit with Benson Boone

“We’re Liverpool boys, and they say Liverpool is the capital of Ireland.” Paul McCartney explains how the Beatles introduced harmonized guitar leads to rock and roll with one remarkable song