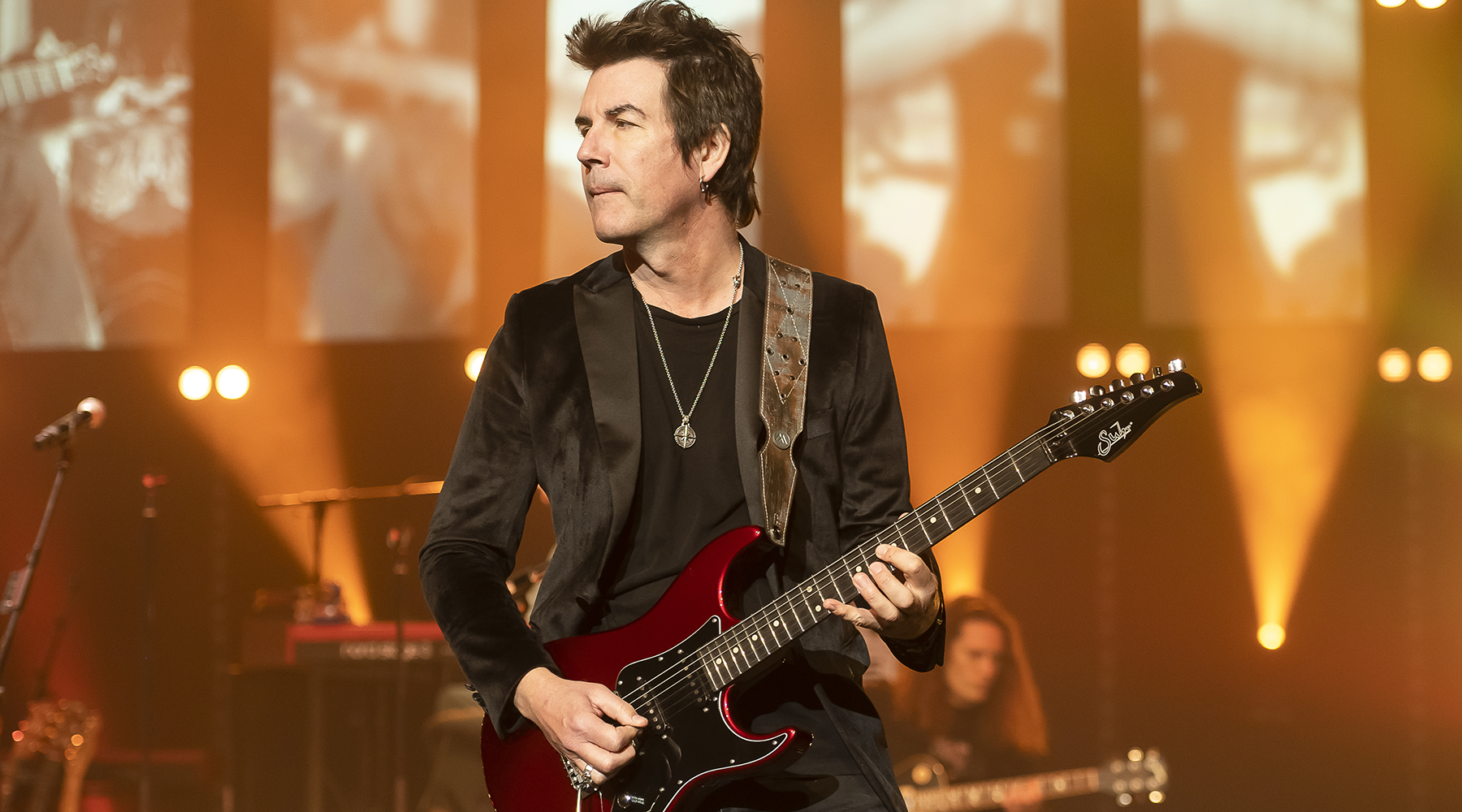

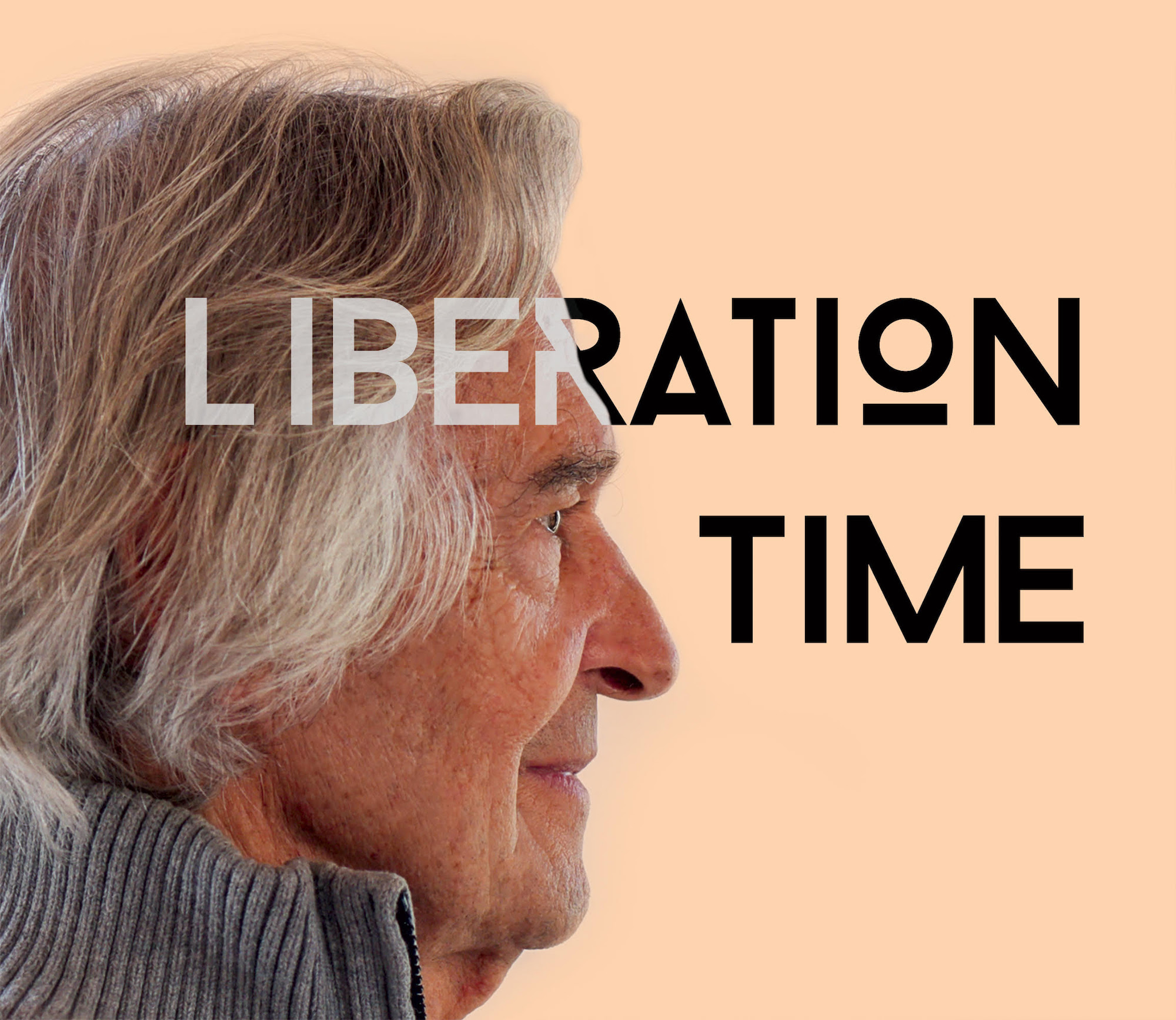

“People Will Either Like It Or They Won’t, But That’s Not My Problem”: John McLaughlin Talks New Solo Album, ‘Liberation Time’

Freedom has been on a lot of people’s minds the past two years and the jazz-fusion pioneer has made it the theme of his latest.

John McLaughlin’s new album, Liberation Time, is his response to the tribulations of the past two years, in a world turned upside down by Covid. With the cancellation of two tours, and finding himself with time on his hands in Monaco, where he has lived for many years, McLaughlin was, by his own admission, starting to go crazy.

Out of his frustration came inspiration, and he started to create a collection of positive, upbeat and joyful tracks that were a celebration of life. Indeed, joy is something central to McLaughlin’s existence. Inspired by nature and life, he finds positivity in the wonders of the universe.

That optimistic and grateful attitude is expressed perfectly on an album that contains some of the guitar master’s most direct and affecting music.

No stranger to readers of Guitar Player, McLaughlin has been a mainstay of the jazz and fusion scene for more than 50 years. Prior to his profile-raising tenure with Miles Davis, McLaughlin had been a member of Brit jazz pioneer Graham Bond’s band, and had worked as a session guitarist on numerous hit singles in 1960s Britain.

His only focus then, as now, has been musical integrity

Leaving Davis to start his own band, McLaughlin ultimately took fusion to the next level with the global success of Mahavishnu Orchestra. Always a musical purist, he followed that by forming Shakti, exploring the boundaries of Indian music and jazz. Although the band was not as commercially viable as Mahavishnu, McLaughlin was undeterred; his only focus then, as now, has been musical integrity.

He has continued to be prolific. Always active on the live and recording fronts, he shows no signs of slowing down and continues to follow his muse regardless of commercial considerations or musical fashions.

Given that Liberation Time was recorded during lockdown, did everybody do their parts remotely?

Yeah, mostly because we had to. Wherever it was possible, I’d have the bass player and drummer work together, though. It was a very difficult time. The record came out of pure frustration. By October of 2020, I was losing it, you know?

But out of everything, instead of going slightly mad with the restrictions, all this music started to come out of my head. I knew I had to do something with it. I was mainly on my own, but there are a number of musicians that I can record with here in the south of France.

My first instrument was the piano, and I still think of myself as a piano refugee. [laughs] I know how to make a piano track sound good. When I was first in America, I loved to play the drums, so I can set up a whole rhythm section on my own to lay down the tracks if I need to.

Playing music is one of the greatest experiences possible if you have intense emotional issues to process

John McLaughlin

I had been going so crazy, but playing music is one of the greatest experiences possible if you have intense emotional issues to process. I’d set up the tracks with everything on them, then send copies to musicians around the world – wonderful players – and they’d have a score and a demo to listen to, but they all had solos to play.

My instructions were “Be yourself.” I didn’t care how crazy they went. I didn’t care if they didn’t want to follow what I’d laid down when I sent them the track to work on.

Did you miss the interactive process of working with the musicians face-to-face?

Here’s an interesting thing: Sometimes the playing would be so great when they sent the track back to me that I’d be moved to redo my original part differently, simply because it was so inspirational.

it was a very collaborative process that wasn’t at all hindered by working remotely

John McLaughlin

When I put the headphones on, it feels like I’m in the room with the players. What was interesting then was that I’d send the track back to the musicians and they’d become re-inspired to change their part again as well, so it was a very collaborative process that wasn’t at all hindered by working remotely.

The mood and character of the pieces often changed and developed and required an evolving approach. This meant that things took a long time, of course, with all the sending of files and booking studio time, et cetera, for musicians around the world.

Liberation Time is a very strong album that covers a lot of ground, from straight jazz guitar to fusion. Are you happy with the end result?

The way the music came out was, to me, a kind of recapitulation of the wonderful ’60s period of jazz with upright bass, in a way more straight-ahead but with electric guitar. It was kind of the classic jazz approach, but with my guitar today.

For me, it is all about the music and the expression

John McLaughlin

It isn’t that I set out to write an album like that; this is just how it came out. I wanted to keep the integrity of the music, but I recalled through the music the pieces that I recorded about 40 years ago, when my piano technique was reasonable. It’s gone a lot since then. There are two piano pieces, and they are perhaps more in the late-’70s era of jazz. I thought that they were very personal, but why not?

It makes me laugh when I think about making money from records. I guess maybe I should try another approach. [laughs] But I’m old-school. I don’t even know how many albums I’ve made. For me, it is all about the music and the expression.

I presume, like most artists, you’re primarily concerned with how happy you are with the music rather than commercial considerations.

Exactly. I can’t stop making music and recording albums, whether they sell fantastically well or relatively poorly. Once the record is finished, it is unchangeable; it’s over. People will either like it or they won’t, but that’s not my problem. [laughs]

“As the Spirit Sings” is a very upbeat opener. It’s indicative of the album as a whole, which has a totally positive vibe. Was that something you were trying to convey?

In spite of the fact I was losing my mind, I’m a very positive person. I think to myself that I’m fortunate to be alive when I think of how many friends I’ve lost over the years. I’m very healthy and I can still play. I don’t know how long it is going to last, but I don’t care. I thought I’d lost it five years ago when I got terrible arthritis, but somehow I found a way to cure myself.

Maybe that is the benefit of 50 years of meditation – you become aware of the nature of existence and your place in it

John McLaughlin

I’m grateful for every day and every minute. Maybe that is the benefit of 50 years of meditation – you become aware of the nature of existence and your place in it. I am in such awe of the immensity of this universe that we live in. I am in wonder and awe at the beauty of nature, and I feel connected to it. I think the reason that I am upbeat is that I feel connected to everything. The joy of playing music and the joy of existence is crucial to who I am.

How did you resolve the problem with your hands?

It was very bad in 2014, ’15. I thought I’d come to the end of my playing life. I was quite philosophical about it. I thought, Okay, I’ve had a fantastic career, and thank you very much!

I met several doctors, and one injected me with a solution of hyaluronic acid [a cushioning and lubricating fluid found in the eyes and joints], which was a fairly new concept, and it was quite effective, but the pain would keep coming back, and it bothered me to keep needing the treatment.

If you persevere, your mind will win

John McLaughlin

I then discovered a doctor in America called Joe Dispenza, who had a bad accident himself, and his back was broken in three places. He’d been told he’d need to live his life in a wheelchair. He started working on his own body with his mind, and I read about this and decided, three years ago, to try this approach.

After six months, I realized that I didn’t need the injections again. The technique is very simple: Every day before my morning meditation, I talk to my hands. I tell them how beautiful they are and how grateful I am for what they’ve given to me in my life and how much I love and cherish them. I do that every day, and I have no pain or swelling.

Isn’t that amazing? If you persevere, your mind will win.

Another interesting track is “Right Here, Right Now, Right On,” which is a prime example of what you were saying about some of the tracks being a real throwback to an earlier age of jazz – the Blue Note small-combo approach. I guess that must be a very comfortable area for you to play in, having been playing that style of music since the early ’60s.

All the tracks are in a comfortable zone for me because they all came out of my head. [laughs] I know them intimately, and they’re like my babies. There is a strong post-bop feel on this one, as you suggest.

To have these players on them is just wonderful. People like sax player Julian Siegel, [drummer] Vinnie Colaiuta and less well-known musicians like [drummer] Nicolas Viccaro. It is so satisfying to hear what they bring to the music.

The musicians know that there will be ensemble playing and space for them to express themselves, and that is where the magic happens.

I told everyone, ‘Be who you are. Be crazy if you want to be, but be crazy in the context of the music’

John McLaughlin

Among a wealth of great soloing from all concerned on the album, the bass solo on “Lockdown Blues” is a real highlight.

Absolutely. That is Etienne MBappé who plays in 4th Dimension, which is my current band. The other two members of the band, Gary Husband on piano and Ranjit Barot on drums, are the remaining musicians on that track.

On “Singing Our Secrets,” it is almost four minutes before your guitar enters. It’s clear that you see the music as an ensemble piece rather than a guitar-centric record, as so many guitarist’s albums turn out to be.

I learned that lesson from Miles and Coltrane, you know. They are my heroes, and I still listen to them today. Take a track from Miles or Coltrane: They’ll all take the melody, then perhaps McCoy will take a solo, or Herbie or Cannonball will take a solo, and Miles will come in later.

The whole philosophy was marked on me and ingrained in my brain: Okay, I’m writing the music and I’m the so-called leader, giving the direction, but the whole point of collective playing is the fact that it is improvisation and interpretation, and this is individual and collective.

I told everyone, “Be who you are. Be crazy if you want to be, but be crazy in the context of the music.”

A track like “Liberation Time” is almost classic fusion and is very guitar heavy, whereas there are tracks like “Mila Repa” and “Shade of Blue” that are almost the polar opposite, featuring only your solo piano. Was the diversity of the album something that was planned or just part of the spontaneous creative process?

The only philosophy that I can hold to is to be who I am, and the devil take the rest. I’ve always felt that if I try to play something thinking people will like this, I’m not only betraying them but I’m betraying myself.

Shakespeare said it 500 years ago: Be true to yourself and you’ll be true to everybody else. [laughs] In music, it is so important. I’m not against people who make records that are trying to please the crowd. It’s just not for me.

The only philosophy that I can hold to is to be who I am, and the devil take the rest

John McLaughlin

Over my career, I’ve had records that were very successful and some that were not so successful. It’s important to distinguish between different kinds of success, There’s commercial success and there is musical success, and it’s not very often that the two come together.

I think hell would be to make an album to please others and then think, Shit! Why did I do that? What an idiot I am! [laughs]

Gear-wise what did you use for the album?

Basically, I used a Paul Reed Smith that I’ve had for about 10 years now. I have a number of his guitars; he’s a phenomenal guitar builder.

I use a Line 6 HX preamp that I got that last year, and I really like it. At the same time, I sometimes use an old Mesa/Boogie preamp in the studio for a number of tunes. I only use preamps though. I haven’t used a regular main amp for years, live or in the studio.

When I play live, I’m fed into the desk and hear myself back through the monitors

John McLaughlin

When I play live, I’m fed into the desk and hear myself back through the monitors. I like to hear it in stereo, so I have my speakers in front and facing toward me. The house gets basically the same sound that I get.

Strings are, as always, D’Addario. I guess I’ve used them for 50 years now, and for a pick I use a Dunlop Jazz III. I think I was the inspiration behind this pick because I used to make something similar for myself and then slash and score them with a knife to help me keep a grip on them. The picks now have the grip built in.

In terms of your own playing, what do you work on?

I’m fascinated by harmony, melody and rhythm. They are all different departments of work, and there are periods of life where I will pay more attention to each area. Articulation of melody is my focus at the moment.

You can hear it in my playing on something like “Liberation Time.” The titles of my tunes are very meaningful to me. The idea of liberation was so important last year. To be free in music implies a lot of very important things: Firstly, that you don’t have any technical problems with your ability to play your instrument. There is the harmonic aspect of improvisation – what are you going to say with your improvisation?

To be free in music you have to have no problems technically, then you need to be inspired

John McLaughlin

All we can talk about when we improvise is our own life story: How deeply we feel and we what we feel about ourselves; how I feel about life, existence, the people I’m playing with, the music I’m playing. This is like the gas in the engine, the emotion behind the intent.

Then you start playing. “Liberation Time” is just two chords. It’s a total steal from “So What,” by Miles Davis. Coltrane stole it for “Impressions,” and Mike Brecker stole it for something else.

We’re all thieves! [laughs] You take the two chords, then decide what to do with them. To be free in music you have to have no problems technically, then you need to be inspired, and you can overcome the limitations of the music.

You then get into harmonic exploration. You need the knowledge to understand what you’re trying to achieve and express. Any note is a good note if the intent is behind it. I like to be inspired by the musicians I’m playing with, to be provoked into trying something new and to take a chance, to walk the high wire and not be afraid to fall off.

You only really get this freedom in jazz, in my opinion. Improvised music brings joy, and joy is not an emotion that you see in the world in general. I’m not talking about happiness, like, “Yeah you have a good job,” et cetera. Joy is the immediate experience.

Any note is a good note if the intent is behind it

John McLaughlin

I see it in my dog when I come home. You see it with kids who can’t even talk yet. Adults don’t have pure joy so easily, and we need joy in this world. There’s far too much heaviness.

Are you still as excited by music as when you started, and what is it that keeps everything so fresh for you after all these years?

I’m alive. Every day is different, every minute, every hour. I’ve never lived this second before. Every second is new. It’s amazing. In meditation, you practice living in the present moment, but the present moment is the most fantastic moment I’ll ever have. I’ve never had it before.

Every moment is a brand-new experience. Most of the time in life people look backward, but I look forward as every moment comes toward me. It’s fantastic. I’m living in perfect stillness.

Time is coming, and I feel it flowing over me, and I give thanks for being alive.

Get Liberation Time here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened