"Do you know what happened to my lost bass, the one that got pinched?" How Paul McCartney's simple 2019 query over coffee in a studio led to a forensic hunt for the iconic Höfner 500/1 violin bass

The theft of Paul McCartney’s 1961 Höfner bass is a 50-year-old mystery that spans from Hawkwind to the Who. Here's how the Lost Bass project filled a gap in rock and roll history.

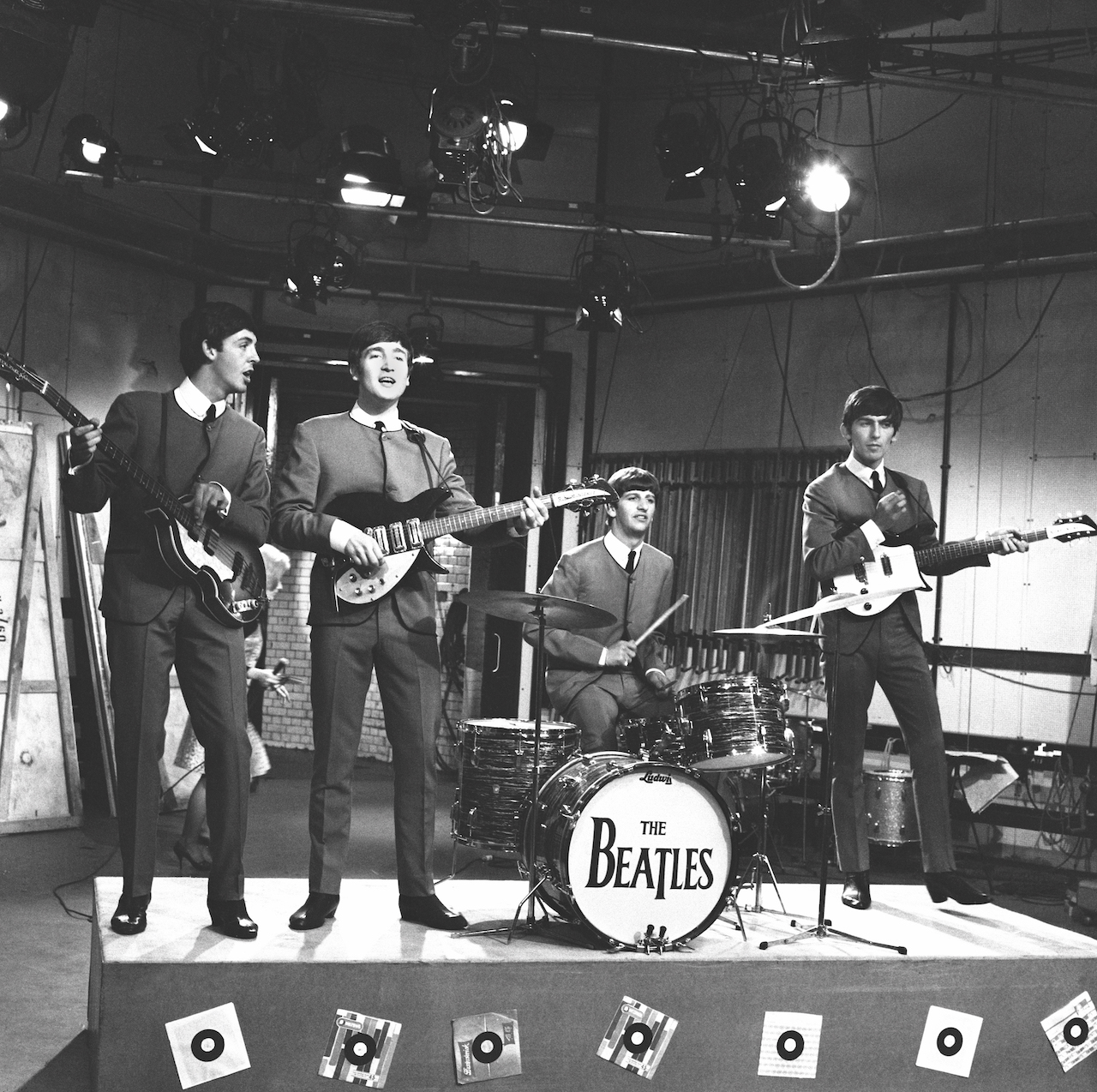

Most fans know it simply as “the Beatle bass.” To Paul McCartney, it’s “the Ancient One,” the instrument that dates back to the guitarist’s musical rebirth as a bassist, at age 19. The 1961 Höfner 500/1 violin bass is the first bass guitar he owned and the one he played as he helped lead the Fab Four to international fame in 1962 and ’63.

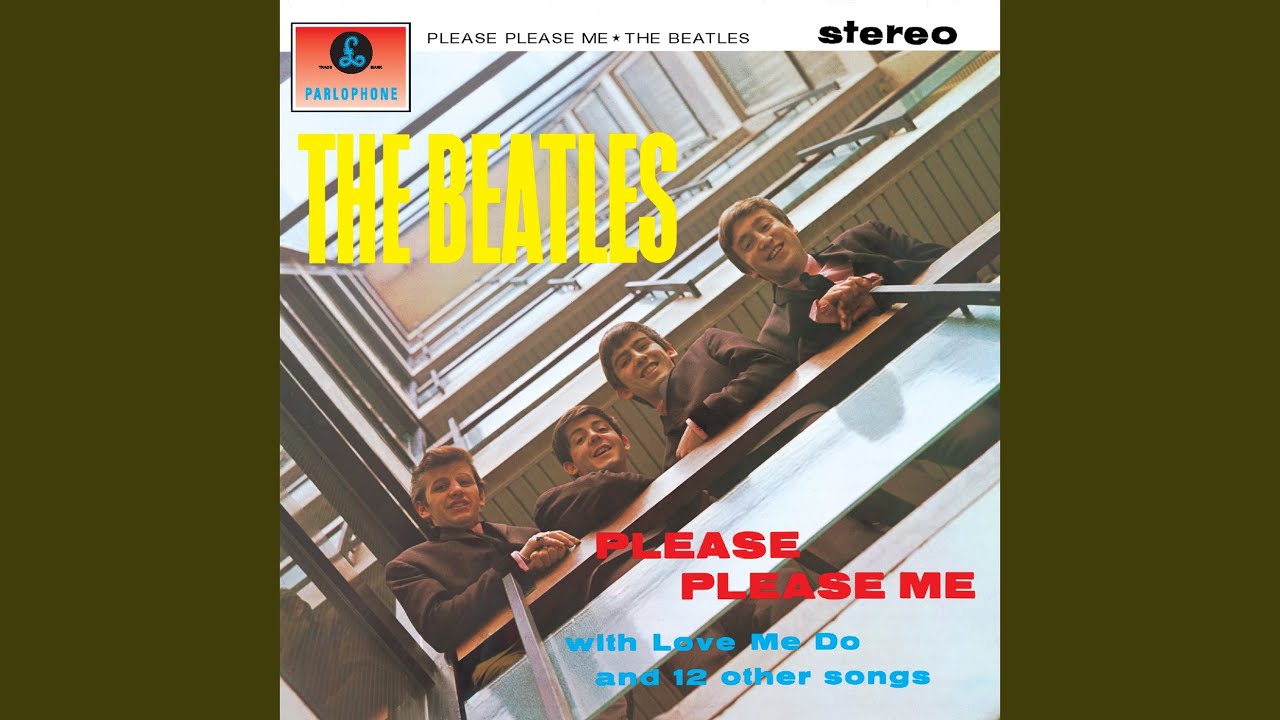

Its round, resonant tone was the indelible pulse that drove the group’s earliest hits, from “Love Me Do” to “Please Please Me” to “I Saw Her Standing There,” where McCartney nimbly plucked out the arpeggiating riff he lifted from Chuck Berry’s 1961B-side “I’m Talking About You.” With a shape as distinctive as the early Beatles’ mop-top haircuts, the 500/1 became McCartney’s signature instrument.

To this day, the Höfner is the 81-year- old’s bass of preference in the studio and onstage. But for more than 50 years, the Ancient One has been missing, stolen presumably in January 1969, while the Beatles rehearsed and recorded the music for Let It Be. Like Eric Clapton’s “Beano” Les Paul, the celebrated electric guitar that graced the grooves of 1966’s Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton, McCartney’s Höfner has taken on mythic proportions, becoming a holy grail for those who who think, talk and dream about rock’s lost treasures.

That fanbase has grown considerably since the launch of the Lost Bass project, a global search for the ’61 Höfner that brought the cold case to the masses this past September. At the head of the search are one-time Höfner GmbH marketing manager Nick Wass, former BBC journalist Scott Jones and television producer Naomi Jones. Although McCartney is not involved, he instigated the hunt with a simple question to Wass in 2019.

“Höfner were making a backup bass for him,” Wass explains, “and we were just sitting drinking coffee in the studio when he suddenly popped the question: ‘Do you know what happened to my lost bass, the one that got pinched?’” Wass didn’t know, but he was intrigued enough to launch a search for it on Höfner’s website and in the German media.

The buzz drew few leads, but it attracted Scott and Naomi Jones, who brought, respectively, useful journalistic and research skills to the effort. Relaunched this past September as the Lost Bass project, the search garnered extensive international attention, thanks in large part to Scott Jones’ journalistic background. (Jones led an exhaustive study into the 1969 death of Brian Jones that provided new insights, as revealed in the 2019 documentary Rolling Stone: Life and Death of Brian Jones.) Within weeks of its announcement in the U.S. and U.K. media, the Lost Bass delivered not only reliable leads but also new insights to when and how the theft occurred, and even who was behind it.

I was left-handed, so it looked less daft, because it was symmetrical

Paul McCartney on 'the Ancient One'

Most remarkable, though, is the discovery that, when the bass was stolen, McCartney declined to report it to the police. Less a decision than a sacrifice, his inaction allowed the bass to vanish without a trace into one of 1970s England’s most notorious, but musically rich enclaves.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The Höfner 500/1 was an attention getter well before it was a Beatle bass. Walter Höfner was a second-generation violin luthier who applied his skills to the hollowbody creation, which he modeled on the upright doublebass. Designed in 1955, the German-made Höfner 500/1 had its public debut at the Frankfurt Musikmesse the following year. McCartney’s 1961 500/1 dates back to the Beatles’ pre-fame days in Hamburg, as the Liverpool rock-and-roll group transformed from a five-piece to a quartet in the grubby clubs of the city’s Reeperbahn nightlife district.

When bassist Stu Sutcliffe quit the band to pursue his career as an artist in July 1961, it fell to McCartney to take over from him; George Harrison was too skilled as a lead guitarist to do the job, and John Lennon had neither the desire nor the ability. McCartney had already filled in for his bandmate during his many absences from the group’s long, late-night gigs. Although left-handed, he was adept at playing Sutcliffe’s Höfner 500/5 bass upside-down, without changing the string order, so that it would still be playable by Sutcliffe when he did show up. But after Sutcliffe announced he was leaving, McCartney began looking for a bass of his own.

Although he strongly desired a Fender, they were hard to come by outside of the U.S., and expensive. “I couldn’t afford a Fender,” he reflected in 1989. “Fenders, even then, seemed to be about £100.” Accounts of what the Beatles were paid for their performances vary, but each of the five appear to have earned around £20 per week. The Höfner 500/1 certainly fit the bill. Costing the equivalent of just £30 in 1961, it was within McCartney’s budget (although he still had to pay in installments). Just as important, he liked its shape. “Because I was left-handed, it looked less daft, because it was symmetrical,” he explained in 1989. In fact, he may have intentionally sought out the model, since he would have seen one played by the bassist for the Jets, the first of the Liverpool groups that made the trek to Hamburg.

It’s possible as well that he noticed a violin-shaped electric model in the hands of Little Richards’ bassist in the 1956 rockand-roll film Don’t Knock the Rock, where Richards sings “Long Tall Sally,” a favorite of McCartney’s and a Beatles cover from their early years. After trying out a right-handed 500/1 at Hamburg’s Steinway-Haus Music Store, McCartney special-ordered a left-handed model, which arrived quickly from Höfner’s factory in Bubenreuth.

The Höfner 500/1 he received had a solid spruce carved top, a three-piece maple neck, 22 frets and a short, 30-inch scale. Its pair of Höfner nickel-plated diamond-logo pickups were set close together near the neck and mounted in dark surrounds, while its rectangular control panel sported two volume knobs and pickup switches for Rhythm/ Solo, Bass On and Treble On.

McCartney would use this bass exclusively for the next two years as the Beatles played their Hamburg dates, landed a recording contract with EMI, fi red drummer Pete Best, hired Ringo Starr, tracked their first hits and two full-length albums, and became stars in the U.K. and Europe. Given the group’s performance schedule, the bass was in constant use from the time he took possession of it. By autumn 1963, its pickups were falling out and the bass seemed unlikely to remain playable for much longer. McCartney ordered a second 500/1 to use over the coming tours, including the group’s visit to the United States, where they made their American debut on The Ed Sullivan Show, on February 9, 1964.

He received his new left-handed 1963 model 500/1 in early October of that year as the Beatles were completing their second U.K. album, With the Beatles, just prior to their debut showing on the British TV music program Ready Steady Go! on October 4. This new model had a pair of Höfner “staple” pickups (so called for their rectangular pole pieces), which, unlike his 1961 500/1, were placed further apart, with one just below the end of the neck and the other just above the bridge. The 1963 model would be McCartney’s main bass in the studio for the next two years and onstage through 1966.

In the meantime, the ’61 Höfner was sent to Sound City in London for extensive rework. In addition to respraying it in a polyurethane sunburst finish, the shop re-affixed the loose-fitting pickups in a mounting plate made of what appears to be black plastic, giving the bass an appearance unlike any other 500/1. The existing pickguard was recut to accommodate the plate, and the controls received new cream-colored knobs. McCartney gave the rehabbed bass its debut at the Beatles’ July 11, 1964 appearance on the British pop music TV show Thank Your Lucky Stars.

Although the 1961 Höfner was relegated to backup duties upon its return in 1964, it subsequently made two noteworthy appearances, both preserved on film. The first was in the promo video for “Revolution,” made on September 4, 1968, with future Let It Be movie director Michael Lindsay-Hogg, where McCartney uses it while miming to the pre-recorded backing track.

The second was in Peter Jackson’s celebrated 2021 documentary, Get Back, created from Lindsay-Hogg’s Let It Be footage, where it’s seen while the Beatles rehearse at Twickenham Studios on January 3, 1969, and later at their own Apple Studios, at 3 Savile Row, in West London. The bass’s appearance at Apple is revelatory, since for years it was assumed the instrument disappeared from Twickenham a week or so earlier.

“Nick had found this chap who worked at 3 Savile Row,” Scott Jones says, “and he was telling him the building was basically a 24-hour party. So it seemed likely someone walked off with it.” That tip gave credence to an earlier lead that the Lost Bass received from a former roadie for the Who, now living in Massachusetts, who claimed he stole it from Apple in late January 1969. (Like all Lost Bass sources, the man’s identity has been protected.)

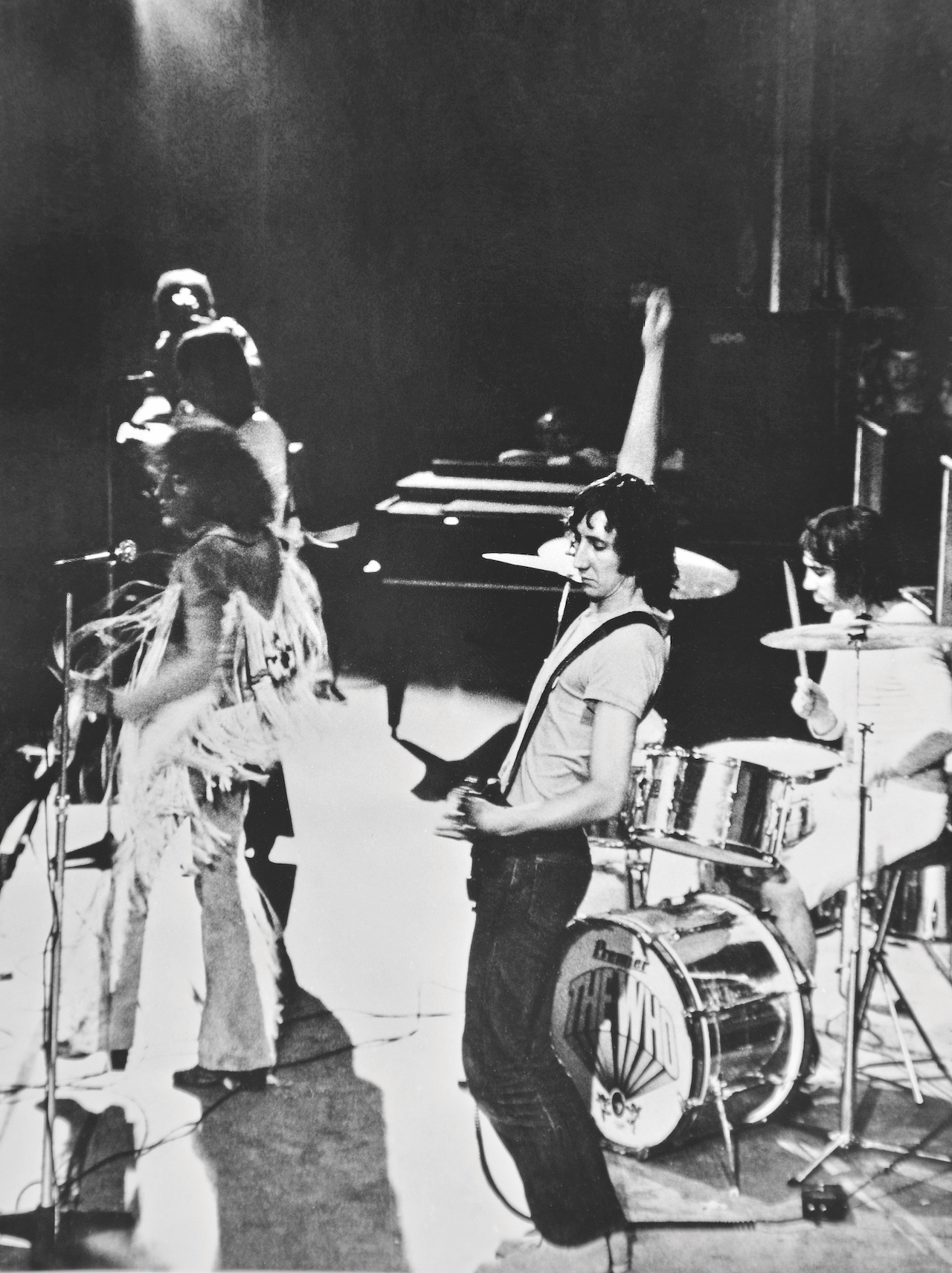

His story was backed up by two witnesses, and Wass confirmed his identity through Who performance footage in which the man can be seen. Concert archives also show that the Who played in West London, at Borough Road College in Isleworth, on January 25, around the same time that the ’61 Höfner is last seen at Apple Studios in Jackson’s fi lm. “It was amazing how much this chap fitted the bill,” Jones says. “We know he worked for the Who, we know he’s stolen things, you know? We basically decided that this guy was guilty,” was sent to Sound City in London for he says with a laugh.

“We even had a retired local police commander from the area interested,” Wass adds. “He was getting ready to go round and knock on the door.” But that theory was quickly abandoned when the Lost Bass project received a critical lead from an authoritative source: Ian Horne, a former roadie who was part of McCartney’s crew in 1972, during the early days of Paul McCartney and Wings. As Horne explained to Wass and Jones, the 1961 Höfner was among the gear he and his fellow roadie Trevor Jones were carting in a van on the night of October 10, 1972 — nearly three years after it was presumed stolen.

“Ian and Trevor had been working very late, to 10 o’clock at night,” Wass explains. “And they left the van parked up in a street in London, in Notting Hill, near Ladbroke Grove, with the gear still inside.” By the time they returned, the vehicle had been vandalized. “Somebody broke into the van and stole some of the gear, including the bass. “This,” Wass says, “was our first clear lead.” The date certainly jibes with McCartney’s recording history. McCartney and Wings were making their album Red Rose Speedway at the time, working in a number of studios, including Island, located in Notting Hill. Furthermore, Horne’s story clicked with something Wass had heard in the earliest days of his hunt. “When I was still doing the search through the Höfner site, I got a slightly strange email from a guy giving me a story about the lost bass that he’d heard from somebody else,” Wass says.

“The story actually pinpointed a particular house in Notting Hill, Ladbroke Grove, and said the bass had been taken from this particular address and then sold to somebody in a pub in West London. I didn’t actually pay a lot of attention to it. It all seemed to be far-fetched, so I just archived the story. About six months later, we got the email from Ian Horne.”

They got a wrench and tried to force Dik to tell them where the bass was

Scott Jones

Notting Hill today is an affluent neighborhood where Goldman Sachs bankers own £5m homes, the place from which Conservative politicians like future prime minister David Cameron emerged in the early part of this century. There is little to show it was once a ghetto for Indian, African, Caribbean and Asian immigrants. “But go back to 1972 and those same houses, most of them were squats,” Wass says. “Lots of bands and writers and graphic designers lived there.”

Given his line of work, Horne knew many of those musicians. And when the bass went missing, he had a strong idea who took it. “Their first thought was that it was a chap named Dik Mik,” Jones says. Michael Davies — a.k.a. Dik Mik — was a keyboardist and electronics manipulator who was among the many musicians in Hawkwind, guitarist Dave Brock’s infamous space-rock group, which in one of its early 1970s incarnations also included Dik Mik’s pal, future Motörhead bassist Lemmy Kilmister.

“Ian Horne thought Dik might have stolen the bass because he lived nearby and he knew Ian worked for McCartney. They got a wrench and tried to force Dik to tell them where the bass was. We know now that Dik wasn’t involved.” Even so, the Lost Bass project was able to begin piecing together an accurate history of the bass’s journey in the first days after it was stolen. Naomi Jones dug through newspaper archives, looking for reports of criminal activity on the night of October 10, 1972. Remarkably, three major British newspapers — The Daily Mirror, The Times and The Evening Standard — all carried news of the theft.

As Scott Jones explains, “None of those newspapers have digitized those news stories. The clippings only exist in the British Library, stored away. That’s where we found them.” These facts gave focus to the project’s efforts. It was now clear that whoever stole the bass was almost certainly in need of cash and quickly sold it. That increased the likelihood it was still in England and in the hands of some unsuspecting owner, rather than hidden away within the society of rare-guitar collectors, who could be just about anywhere in the world.

“Now that we’ve got particular addresses from that area, we can go back to the electoral register from ’72 and get names and profiles of people who lived and worked there,” Scott says. “It’s a slow process, but it’s forensic.” Slow, perhaps, and yet it has delivered results faster than anyone imagined. Within two months of the project’s launch, the team had even learned who stole the bass, although that person’s identity — like that of the former Who roadie — remains confidential. When contacted for this article in late November, Wass was all but certain the bass would be found within weeks.

“I think it’s fair to say that. I think you’ll see this bass after Christmas,” he said cryptically and with barely concealed joy. If so, perhaps the only question that remains is what took so long? Had McCartney reported the theft to the police when it happened, the ’61 Höfner might have been found within days rather than decades. His silence, it turns out, was an act of kindness. “The roadies were very loyal to Paul, and they were very good roadies,” Wass says. “And Paul’s feeling was that if this was published or made to be a big, big story, the newspapers would say, ‘Oh, these two idiots lost Paul McCartney’s bass!’ And he didn’t want that to happen. So he just kept the story quiet. Forever.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.