“No Matter Where You’re at in Life: There’s so Much to Learn”: Revered Singer-Songwriter Jim Lauderdale Opens up About His Decades-Long Musical Evolution

As he drops his 35th album, ‘Game Changer,’ the Americana stalwart is learning to be a better musician

It’s uncommon to find a veteran musician who has earned two Grammy awards, made 35 solo albums and amassed a Rolodex filled with first-call players, and who also readily volunteers his shortcomings at his craft. But revered Americana singer-songwriter Jim Lauderdale has elevated the practice of politely deflecting praise to an art.

Over a series of video calls from his Nashville home, he is careful to acknowledge the players who showed him licks and tricks and played on his records. “I still have so much to learn,” he admits, a sentiment he repeats during our conversations.

Lauderdale isn’t being coy. While guitar and banjo are only two of the many instruments he can play, he skipped the guitar lessons and learned to play the six-string by ear, intuition and feel. As an adherent to the singer-songwriter traditions of Gram Parsons and John Prine, his main goal over his four decades of playing music professionally has been to write compelling songs.

“Once I started writing songs in my late teens, it became a real obsession, and still is,” Lauderdale says. “Song-writers like Dylan, Robert Hunter, Elvis Costello, Lucinda Williams, Lennon-McCartney, Jagger-Richards and Gram Parsons – I gained so much inspiration from them, and they inspire me to try to improve constantly.”

Lauderdale is a chameleon of American roots music and the common denominator among some of the biggest names in the musical styles grouped together as “Americana.” He’s collaborated with Ralph Stanley and Buddy Miller, co-written with Grateful Dead lyricist Hunter, and recruited Luther and Cody Dickinson of North Mississippi Allstars to produce and play on his records.

He takes the same approach with guitar players: Only the best will do. The first record he made was a self-titled 1979 duet with mandolin player Roland White that was tracked in bluegrass pioneer Earl Scruggs’ basement and featured a young Marty Stuart. (Rejected by labels, it didn’t come out until 2018.)

His guitar cabal has also included legends James Burton and Dobro/steel master Al Perkins, two of his all-time favorite players. In recent years, Chris Scruggs (a grandson of Earl), Scottish import Craig Smith and steel player Russ Pahl, among others, have risen to the occasion.

“I was working on Time Flies [2018] when Chris first came in to play on a song called ‘It Blows My Mind,’” Lauderdale says. “And Chris’s guitar part did blow my mind. It was so creative. It changed the sound of that record for me.”

On his new album, Game Changer, it was Smith who impressed him.“I felt like Craig really went somewhere with the B-Bender solo on the title track,” he reveals. “It really grabs me when I hear that solo. It’s one of my favorite solos out there, period.”

Lauderdale’s journey to guitar wasn’t a straight line. After honing his rhythm chops on drums, he became interested in harmonica after hearing Hooker ’n Heat, the 1971 collaboration between John Lee Hooker and Canned Heat.

Following his introduction to bluegrass as a teenager, Lauderdale took up banjo. While his interest in bluegrass and traditional American music forms stuck, his instrument of choice shifted to guitar as he tried to emulate the rhythm playing of Clarence White of the Kentucky Colonels and Doc Watson.

Although his own country music career stalled in the early ’90s – his debut single, 1988’s “Stay Out of My Arms,” briefly popped onto the country radio charts, then vanished after three weeks – he has written or co-written hits for George Strait, the Chicks, Elvis Costello and Blake Shelton. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he keeps a zen-like perspective on his fortunes.

Other people recording my songs allowed me to this day to just do whatever I wanted to

Jim Lauderdale

“Other people recording my songs allowed me to this day to just do whatever I wanted to,” he says. “So I went back into bluegrass and traditional country, a kind of eclectic country, singer-songwriter, blues, rock and soul. I’ve been able to run this whole gamut of styles that I really love.”

Game Changer, his 35th long-player, spreads all the best elements of traditional country music – shuffling beats, soaring melodies, weeping steel guitar and plenty of Tele twang – over a dozen songs recorded at Blackbird Studio in Nashville and co-produced with Jay Weaver.

“Country music is constantly evolving, but I’ll always have a soft spot in my heart for steel guitar and a Telecaster,” Lauderdale says. “I have done my job on this record if people who love classic country feel like they can put it on, or have it in their collection, and it would fit right in.”

He spoke with Guitar Player about the new album, his favorite guitar and how he plans to keep getting better at playing it...

You recently said you still feel like a developing musician, yet Game Changer is your 35th album. How does that work?

With each record I do, I feel like in some ways I’m starting over, and I don’t take anything for granted. There’s a certain anticipation. I really want to create something good, or go for greatness, and you never know what’s gonna come out.

With each record I do, I feel like in some ways I’m starting over, and I don’t take anything for granted

Jim Lauderdale

A lot of times in sessions, when I have time booked and I don’t have anything done at all, it really forces me to go somewhere inside of myself and let something come out – let the creative process take hold. And I just hope and pray when that happens, that something worthwhile comes forth that day.

I have certain things in mind, conceptually. Like, “Hey, I’m gonna do a country record,” or “I’m gonna do an edgy country record,” or a bluegrass record. That helps me structure things. But I never assume it’s gonna be easy, and sometimes it runs the gamut from being exciting to fraught with anxiety and anguish. But with [Scruggs and Smith], I’m surrounded by this comfort of knowing that together we’re gonna go somewhere.

It’s such a great feeling to have this confidence in these guys that are just gonna play incredible stuff. Especially with country music. They have such a vast knowledge of tunes. They’ve played so much and played practically everything in the country music catalog, so I can say, “Hey, is this melody derivative of something?” It’s invaluable to have them go, “No,” and it’s a big relief when that happens.

You were doing this Americana-roots thing long before there was a consensus on what to call it. What’s your perspective on your stylistic meanderings under that umbrella?

Well, I’m very comfortable in this world, and I am so glad for our veteran country artists like Johnny Cash or Merle Haggard, who still get played on Americana radio. You can hear older stuff, like Hank Williams, but also roots rock that you might not hear on an oldies rock station – deep cuts of the Grateful Dead, the Band, these groups that were kind of the quintessential Americana bands – and also artists from the singer-songwriter world with people like Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, John Prine and Emmylou Harris. It’s been great to see all of that unfold and grow.

With this record, the musical theme was based in traditional country music, and steel is essential to that

Jim Lauderdale

Chris Scruggs pointed out to me how Game Changer has more steel than your last several records. Was that intentional?

It just happened that way. Ever since I first heard the steel when I was a kid, it fascinated me and touched – no pun intended – some chord inside of me. There’s just something about it, and I love it. With the new song “That Kind of Life (That Kind of Day),” that riff came to me right as that song was starting to get formed.

I’ve learned it’s okay to sing pedal-steel parts to a pedal-steel player, or sing guitar riffs to a guitar player, and that they don’t resent that, that it was okay. So I’ve done that. Sometimes it’s just totally up to the steel player and guitar player, where it’s just like, “Whatever you hear,” especially if I am under this self-imposed pressure in the studio and not really sure what we’re gonna record, and I have these incredible players waiting.

But if I hear something, I enjoy sharing that with the players, and then we build on it. I felt like, with this record, the musical theme was based in traditional country music, and steel is essential to that. The steel is kind of the backbone of this record in a lot of ways.

How did Coco, your 1994 Collings acoustic guitar, become your number one?

Luther Dickinson, who produced Black Roses [2013], really loved the sound of my first Collings, this 1994 D2H A Sunburst, and so that’s what I played on that record. And when I was recording Blue Moon Junction [2013], I borrowed some other, older guitars and brought ’em to the Butcher Shoppe, which was a place John Prine owned in Germantown in Nashville.

I auditioned about six or seven guitars, and [engineer] David Ferguson selected the D2H A. There’s something about it that just really sounds great in the studio. It has been so banged up through the years I’ve had it. I guess I’ve had it now 28 years.

Luther Dickinson, who produced 'Black Roses' [2013], really loved the sound of my first Collings, this 1994 D2H A Sunburst

Jim Lauderdale

What was your affinity for it before people began to identify it with your sound?

When I went to Gruhn Guitars in 1994, when they were downtown, I was looking at several things, and that Collings just really stood out and felt right. I took it to England several years ago, and when I got back I was getting ready to go onstage when I noticed a crack all the way around the sides of the guitar. And so I took it to Joe Glaser’s, and they fixed it, but I was very reluctant to take it out again.

I was fortunate to be asked by Jerry Douglas to go over to Scotland a few years back, and I didn’t bring Coco; I brought another Collings, a D1 mahogany, which I’ve used a whole lot. And Jerry said, “Where’s that Collings?” I told him I was afraid to bring it. He said, “You always ought to use that guitar. That’s an iconic guitar. You should never use anything else.” So I’m starting to come around. After all of these years, it has an even woodier tone.

You were a banjo player first. Did those picking techniques translate to the guitar for you?

I’m starting to do a little bit more fingerstyle stuff, but for years I just didn’t really do it at all. But that’s the beautiful thing about no matter where you’re at in life: There’s so much to learn. And when you learn these little things, they all of a sudden open up new doors. It’s such a great feeling to go, “Hey, I didn’t know this! I never played this chord like that.” So discovering new things is really fun and rewarding.

Do you spend much time learning new chords or voicings, or other new ways to express your ideas on guitar?

I’ve got a long road ahead of me, but I’m gonna enjoy learning a lot of new stuff

Jim Lauderdale

I have so much to learn still. An old friend of mine named Scott Ainslie plays clawhammer banjo and fiddle, and he’s also a great acoustic blues player. I was teaching songwriting last summer at this thing called the Swannanoa Gathering, in North Carolina, and during the songwriting week they also have guitar week.

Scott is one of the instructors, and I was taking his class in blues playing – like Reverend Gary Davis stuff, with a lot of thumb technique, which was totally new to me. At Scott’s website you can subscribe to receive his pre-taped lessons for some crazy low price. So I’m gonna dig into that.

There’s so much I have to learn with bluegrass and acoustic, Piedmont blues and Delta blues. It’s a challenge for me to be in the pocket with the rest of the band. So I’ve got a long road ahead of me, but I’m gonna enjoy learning a lot of new stuff.

I regret not taking lessons earlier. For some reason I thought it’s better just to pick things up, but I think I missed out on a lot by not having more lessons. I had a few in the early days, but not extensively.

When I was teaching the songwriting course at the Swannanoa Gathering, I took a class with Greg Ruby on gypsy swing guitar, which I love to hear, and one with Danny Knicely and Josh Goforth on bluegrass guitar.

Just being up there those five days, I learned a lot from all of those guys – like the subtleties of playing at different volumes, with different attacks. That opened up a new world for me. You get these increments of knowledge that make you wanna learn more and more. It’s gonna be a lifetime ahead of me of enjoyably learning how to play better.

The new generation of bluegrass flatpickers is turning heads. Are any artists catching your ear?

It’s gonna be a lifetime ahead of me of enjoyably learning how to play better

Jim Lauderdale

I’ve been doing some recording with a group called the Po’ Ramblin’ Boys, and they are really in that traditional Stanley Brothers/Jimmy Martin style of bluegrass that I love so much. There’s also a group called Songs from the Road Band, who are based in traditional stuff, but they have that ability to be jammy. They remind me a lot of New Grass Revival on their first album.

The thing about bluegrass, it never ceases to amaze me how performers like Billy Strings and Molly Tuttle, since they were probably nine and 10, were great players, and where they’re at now is just mind blowing. And when you think these players have reached a peak within the bluegrass style, they oftentimes will go somewhere else and further blossom as a guitar player, and then when they come back in and do bluegrass again, it’s at a whole different depth.

Watching Molly and Billy, and when I see the Punch Brothers and when I’ve seen Jerry Douglas – my jaw literally drops and I laugh out of joy from hearing such beautiful and amazing playing. I think when we hear stuff like that, it’s a healthy dose of something that hits our brains, and our bodies too, that is just transcendent.

Order Jim Lauderdale's Game Changer here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jim Beaugez has written about music for Rolling Stone, Smithsonian, Guitar World, Guitar Player and many other publications. He created My Life in Five Riffs, a multimedia documentary series for Guitar Player that traces contemporary artists back to their sources of inspiration, and previously spent a decade in the musical instruments industry.

“I did the least commercial thing I could think of.” Ian Anderson explains how an old Dave Brubeck jazz tune inspired him to write Jethro Tull’s biggest hit

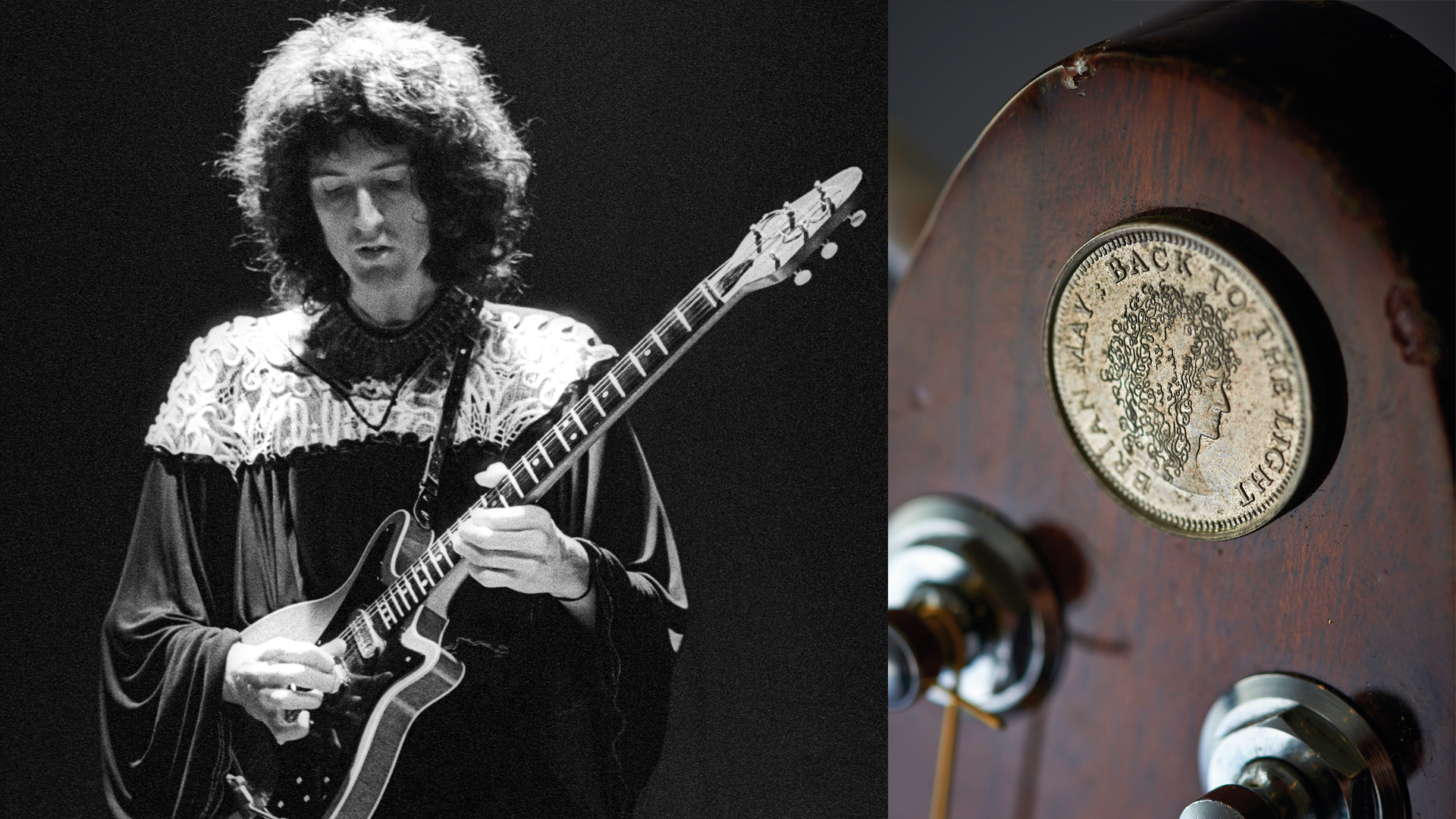

"This 'Bohemian Rhapsody' will be hard to beat in the years to come! I'm awestruck.” Brian May makes a surprise appearance at Coachella to perform Queen's hit with Benson Boone