“When the Vocal Stops, You Want to Make Sure That the Audience Isn’t Bored”: Neil Giraldo Details His Philosophy for Crafting Great Guitar Solos and Reflects on Career Highlights From Rick Derringer to Pat Benatar and Beyond

The multiple Grammy winning-guitarist savors his Rock Hall induction and raves for the musical ‘Invincible’

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As Pat Benatar was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame last November, she looked at the man to her left with a bright-eyed, adoring look. “And you…my partner, my love,” she said, addressing Neil Giraldo, her husband, fellow inductee and musical partner since the beginning of her recording career, in 1978. “I’m guessing we could probably have done this separately on our own, in our own ways. But it never would have been this much fun.”

While her name may be on the records she made, Benatar is adamant that the act has always been the two of them. Together they’ve sold more than 35 million albums worldwide, five of them Platinum, and scored 15 top-40 singles along with four Grammy awards. Giraldo likes to say, “I know where every note is buried,” and Benatar has never been patient with those who would give him short shrift.

“I’ve lobbied for the past 25 years to get him the credit he’s due,” she said prior to the ceremony, confirming that she’d held up discussion about their induction until she was assured Giraldo – with whom she’s had two daughters and three grandchildren – would get equal billing. “The first song we recorded was ’Heartbreaker,’ and that set the tone for everything. The synergy that happened between us was what began everything. To have done what we did, and to work side by side with my bandmate, who’s also my husband, for me that is a huge deal.”

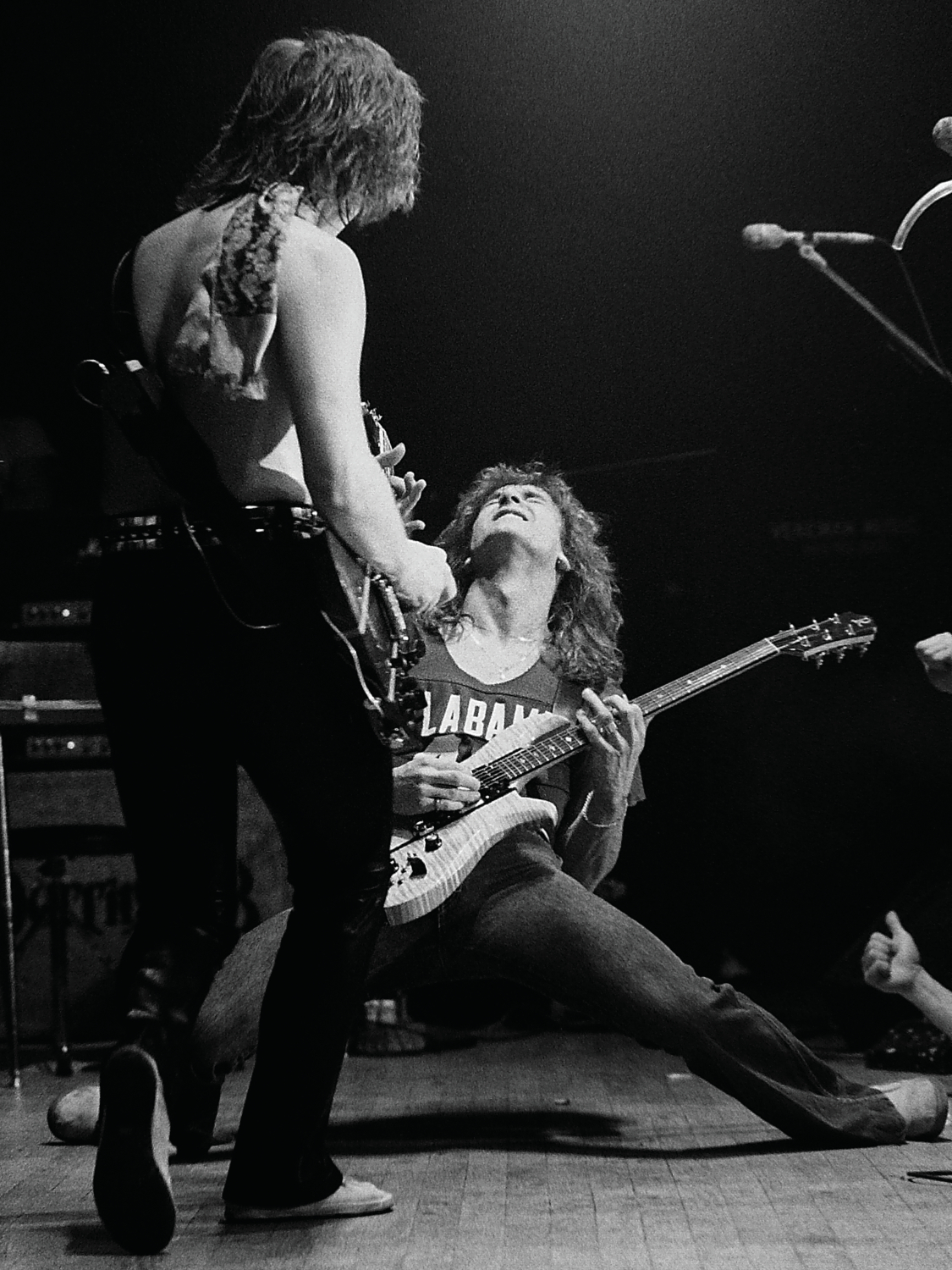

Article continues belowGiraldo’s work with Benatar, meanwhile, is just part of his musical story. He turned pro in 1978 when he joined Rick Derringer’s band and made the album Guitars and Women. He was recruited for Benatar shortly after that but also made his mark playing, writing and producing for acts like Rick Springfield (including the hits “Jessie’s Girl” and “I’ve Done Everything for You”), John Waite, the Del-Lords, Kenny Loggins, Steve Forbert, the Corrs and Beth Hart.

It’s been a while (nearly 10 years) since their last album, and three years since Giraldo and Benatar’s last single, “Together.” Their main project of late has been Invincible, a stage musical, still in development, that re-envisions Romeo and Juliet to a soundtrack of their songs. It’s another fresh adventure in a career that’s seen an abundance of twists and turns – and one that’s given Giraldo plenty to reflect upon on this afternoon at home in Los Angeles.

You’re in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame now. How was that?

I think it’s fantastic. It’s an interesting thing, because in so many ways I felt like I cut in line, y’know what I mean? There’s no Son House. There’s no Wynonie Harris in there. So it’s a slightly odd feeling. I’m certainly grateful, and it’s an honor. It’s one of those things you never think about when you’re six years old and you get a guitar and you’re practicing and playing.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The idea that the “act” is Pat and Neil is something the two of you worked hard to establish.

In the very beginning, Patricia and I entered into a 100 percent partnership. Nobody was allowed to know that. It was supposed to be kept secret and just have her name on the albums. But we found something in each other. All I’ve ever wanted was a great singer, and what I got with Patricia was exactly that.

All I wanted to do is write songs and make records and play and just do all the things I love to do with this great singer, and it didn’t matter what you called it. The record company wanted to do things a certain way, so they did. But it’s always been a partnership for both of us.

How did you and Pat get together in the first place?

I was with Rick Derringer, in the Derringer band. We did a record called Guitars and Women; I played more piano on it than guitar. I got a phone call from a record company and they say, “Listen, we signed this girl. She had a failed attempt trying to get a band together. We’ve heard great stuff about you. Could you come and meet her? If it works out well and you guys get along, then it’ll be great.”

And I say, “Sure, but can I get a free ticket back to Cleveland if it doesn’t work out?” He says, “Yeah, no problem.” And that’s when I met Patricia. I didn’t bring a guitar or nothin’; I just sat there on a piano and talked to her about songs and things – what she was looking for. And that’s how it began.

In the very beginning, Patricia and I entered into a 100 percent partnership. Nobody was allowed to know that

Neil Giraldo

Did you know what it should sound like from the get-go?

Patricia wanted a sound, a band sound. She always put it in the phrase of she wanted to be Led Zeppelin. She wanted to be this singer and frontperson, but she wanted a guitar player, a writer, a partner. And after that first record was finished, I knew something was happening. I just felt it. I remember when the record was finished and Johnny Winter heard it. He loved it. He goes, “Wow, I really love what you’ve got going on there. This is a calling for you.” That was a special moment.

The Derringer band was your big break, right?

It was. Rick auditioned over 200 guitar players. I thought I had absolutely no chance of getting that gig. I had a white T-shirt on, a rope belt, a pair of jeans, white sneakers. My hair was a mess. I had one guitar, an SG. I was listening to these other players, and they were blowing me away. They were phenomenal.

What Rick saw in me was, “Ah, he’s a guitar player, but he does other things!” I play piano. I play drums. I write songs and I love song structure and producing. It was a perfect match. And it was a perfect education period I had with him. Rick is such a brilliant, brilliant player. It was an inspiration to see him play and hear him play.

He taught me so many things when we made Guitars and Women. Todd Rundgren was producing it with him, and I was right there in it and learning the process of making records. The other thing that was interesting with Rick was I had just turned 22 when I joined his band, and he was the same age when he joined Johnny Winter, so he liked the fact that I was sort of like him in a way. It was very cool.

You started playing guitar when you were six years old. Was this interest out of left field?

No. I mean, I wanted to be [Cleveland Browns running back] Jimmy Brown, man. I played street football and wanted to be that. But my ears and my soul of music was there from the very, very beginning, so when I got that guitar it was, like, fate.

You pronounce it git-tar. Is there some southern heritage in the family?

[laughs] No, it’s because I’m Sicilian – chitarra. It’s always been git-tar to me. My dad wanted me to do Italian songs with my sister. That’s the reason he got me the guitar for my birthday.

So how did you migrate from that to rock and roll?

That was all the music I heard: Elvis and all that stuff. My mother was playing it. But the lessons and learning to play were just awful. I hated it.

What Rick [Derringer] saw in me was, 'Ah, he’s a guitar player, but he does other things!' I play piano. I play drums. I write songs and I love song structure and producing

Neil Giraldo

How did you get over the hump?

My uncle Timmy was my mentor. He’s only four years older than me. He brought to my attention the British Invasion and the Yardbirds and everything else that was going on. That’s what really got me excited.

You have mentioned in the past that playing guitar helped you in a more intensely personal way.

Yeah. I was a very sick child. I could barely go to school. I had neurosis problems; as soon as the classroom door would close I’d look around the room and see all these people, and the radiator was super hot, and I’d start sweating and have anxiety and feel like I was gonna throw up. My stomach would be turning inside out. I had a terrible stomach, which actually ended up being pancreas issues I never knew about as a kid. I had separation anxiety.

But what gave me hope was I could play guitar. I could understand the instrument. And I could understand piano when I was 10, and then drums made sense to me. It was a natural thing for me, and it gave me hope. ’Cause I couldn’t be Jim Brown. The genetics were totally wrong.

Considering that anxiety, it’s ironic that you’ve made your life’s work playing in front of large crowds of people.

I was able to manage the disease, the sickness, the neurosis. And once I found out what the pancreas issue was many, many, many years later, that helped. But, yeah, music was the only thing that gave me any kind of hope. When you play music, it releases endorphins. It feels amazing. And then when you hit on something, you go, “Wow, I can actually play that? This is great!” So it really feels satisfying.

Who were your early sources and influences?

The Kinks, the Stones and the Yardbirds. The death of Jeff Beck is so tragic, ’cause to me he was the greatest. But who I really wanted to be was Pete Townshend. I wanted to write the songs and play multiple instruments and sing some – not a lot, but enough to get the melodies across.

A lot of those British Invasion bands came out of a blues infatuation. Did you trace their steps backward into that?

I loved the blues. My mother would take me to Woolworths and Kresge and give me a dollar to buy anything I wanted, and I would buy records. You could get 10 records in cellophane – 45s without jackets on them – and I would take ’em home and put them on the record player. I would listen to all the A sides, and then I’d flip ’em over and listen to the B sides.

I loved the Beatles, but I loved George Martin more. I wanted to be Sam Phillips

Neil Giraldo

So I was listening and playing along to [American R&B singer and saxophonist] Bull Moose Jackson, Chuck Berry, other people... I didn’t know who they were. I didn’t know what they looked like. John Lee Hooker was in the batch. Muddy Waters was in there, Chess Records – all these things.

The records were cut-outs [overstocked and discontinued merchandise sold at discount], which I didn’t know about at the time. I was just picking up whatever I could and listening and playing along.

How did you get interested in the other disciplines, like producing and arranging?

I loved the Beatles, but I loved George Martin more. I wanted to be Sam Phillips. When I heard “Heartbreak Hotel” for the very first time, I felt like I was walking down Lonely Street. I heard the bass, the thunderous low end, on that record, the spaciousness of it, the vocal, the reverb on Elvis’s voice, the depth – the whole thing. I’m thinking, “Who did that? Who’s behind that?” And I realized it was Sam Phillips, and was like, I wanna be him! That’s what I wanna be. I want to write those songs. I want to produce records like that.

What’s your philosophy for crafting a guitar solo?

It’s simple: When the vocal stops, you want to make sure that the audience isn’t bored. You want to give them some sort of melodic energy to carry it through until the vocal comes back. So I would take the last note of what the vocalist was singing and start around there, whether it would be that note or the root or an octave higher, or it would be a fifth or whatever it was. I would take that note, and I had no idea what I was gonna do next, but I knew how it was gonna come out of the solo.

I just wanted it to be a conversation that related to the subject and the context of what the song was about. I would just tell the band, “When it gets to the solo section, let’s do 12 bars and see what happens” and then build it from there, but always in the context of the song and what it was about.

I had that 31 measures or whatever it is, and I was really struggling at that particular time in my life. There was way too much going on, way too fast. It was getting hard to handle, with everything that was going on with Patricia, and having a number one record with Rick Springfield’s “Jessie’s Girl,” and Ozzy wanting me to do his record, and I had John Waite’s first solo record...people calling left and right. So I was really having a tough time.

I come into the studio, and I brought a bottle of vodka in, and I said, “Listen guys, I’m only good for about half an hour. Let’s run it through a couple times. If I get it, great. If I don’t, we’ll come back another day.” I did, like, three or four passes and said, “That’s enough. Let’s listen to it tomorrow.”

And I had it. It just happened. I don’t know how it happened or why; it probably had something to do with the texture of the song. I was in a really bad place and it communicated that way. It just happened to work.

Speaking of surprises, the Invincible musical has certainly been an unexpected pleasure.

It has, yeah. Theater is a whole different animal from the recording industry. But even in theater, you have to be disruptive if you want to survive. I believe Hamilton was so successful and really so transformative because it took chances and it was disruptive. I don’t think it was that far of a stretch from the norm, but many people in theater thought it was very, very different. Hadestown was disruptive in a way; it brought a different type of music and sound to theater, which I loved.

What was it like to mess with these songs that are so well-known and established from decades of airplay and concerts?

I really like the idea of re-orchestrating and changing them. I wouldn’t want to do a jukebox musical, where you re-create the exact same arrangements and everything. I have no interest in that. So changing things up and putting a string quartet in place of the guitar – that interests me. And percussion – a lot of drums, a lot of rhythm. I enjoyed doing that, and I intend to do even more to make it more intense.

What are the plans for it now?

We’re in talks. Patricia and I are both producers as well, so we’re talking to the production team about where we’re gonna go from here with it. There’ll be some changes. Each incarnation of the show gets better and better, and the latest one took a giant leap from where it was before. I’m thinking we’ve got one, maybe two more versions at most, and then we can be where we want to be.

Anything going on in the way of new music from you guys?

My drummer buddy Myron Grombacher and I have written a bunch of songs, and we’re gonna go in and make some racket together and some new music, which I think sounds really exciting – not unlike the Black Keys. I like the idea of just the two of us making all the noise. I might incorporate another instrument in it – maybe a bass trombone or some kind of interesting combination of tones and create some different sounds.

Any plans for new music with Pat?

No, we’re not doing anything at the moment. She’s the one in charge of the administration and going forward with Invincible – talking about the direction of where that should go, how the story should be changing, what’s going to stay the same, and where she hears the music going. That’s her thing. I’m going outside the lines and working on stuff of my own – my different kind of wild trouble I can get into.

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.