“My Goal Was Simply Longevity – to Have a Long Career – Not to Become Famous”: Steve Lukather Looks Back on His Extraordinary Life as a Guitarist

The following appeared in the February 2018 issue of Guitar Player

When Steve Lukather was a kid, he had a recurring dream: He’d walk onto a huge stage in front of a vast audience with a guitar in his hands. “But right before I’d play my first note,” says Lukather, “I’d always wake up.”

It was only in real life, at age 19, that Lukather finally experienced that dream.

“The first real show I played was at Red Rocks Amphitheatre with Boz Scaggs,” he says. “There’s a photo of me at soundcheck with this huge grin on my face, because I’m like, ‘This is my moment. I’m having the same old dream, but, this time, I know I’m not going to wake up.’ It was a magical night. It changed everything for me.”

Fast forward to October 21, 2017, and Lukather is living another dream: He’s turning 60 years old at Planet Hollywood Resort and Casino in Las Vegas while backing a Beatle. “Why do I have Steve in my band?” says Ringo Starr before the show. “Because he was free [laughs]. He’s also good at getting the audience to stand and clap. Showbiz is his middle name.”

Lukather’s tenure with Ringo Starr and His All-Starr Band is just one of many dream gigs the guitarist has lived out on stage and in the studio. The dreamiest gig, of course, is Toto.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Showbiz is his middle name

Ringo Starr

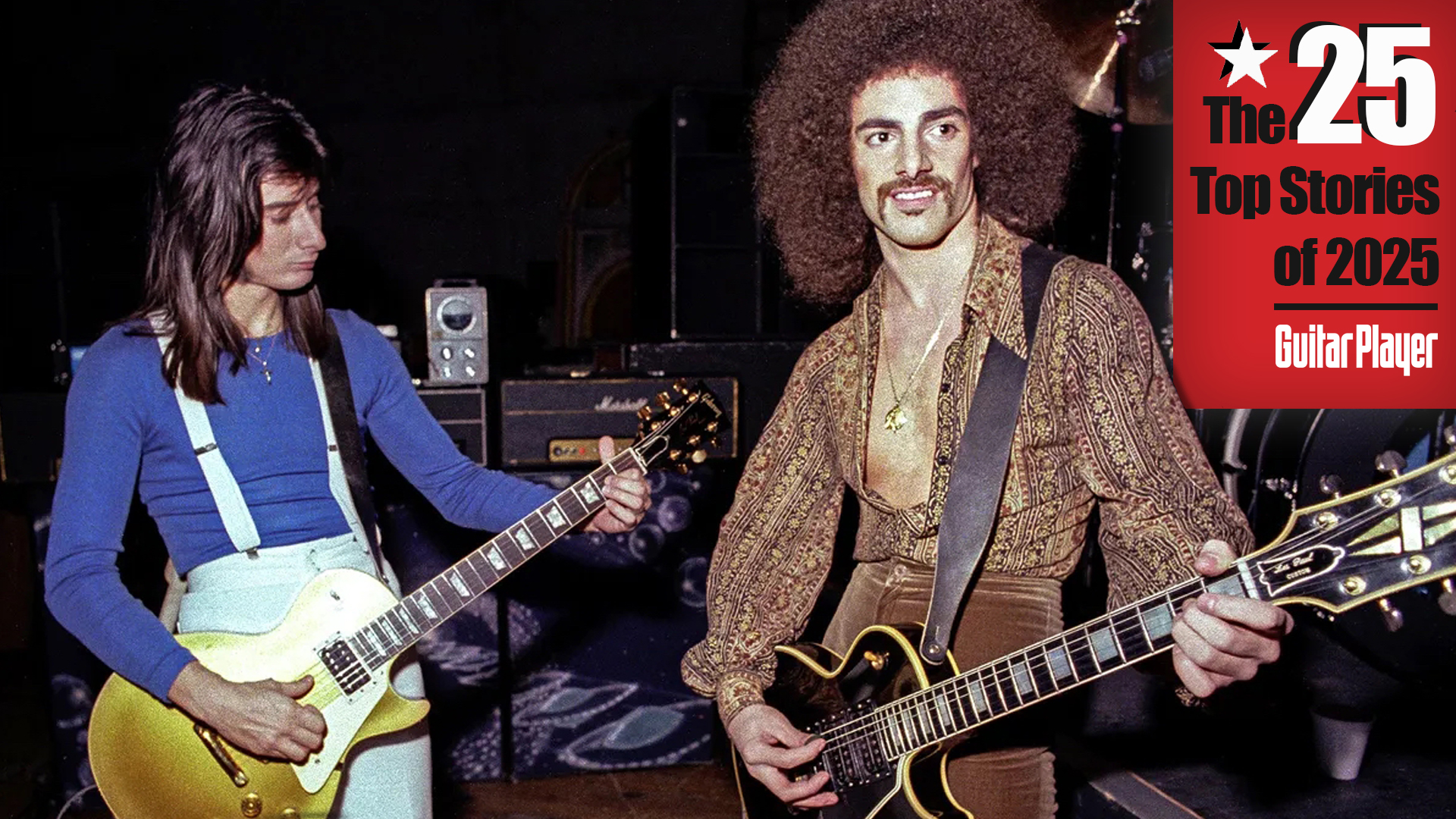

Lukather established the multi-platinum rock group in 1977 with his North Hollywood homies (keyboardist David Paich, and the Porcaro clan of keyboardist Steve, drummer Jeff, and bassist Mike) – the same posse of studio aces who worked with Lukather in various combinations on legendary recording sessions for Boz Scaggs, Randy Newman, Michael Jackson, Don Henley, Lionel Richie, Quincy Jones, and other superstars during the golden era of session work in the late ’70s/early ’80s.

You can read all about it right from the source. Lukather’s adventures during the session era and beyond are detailed in the guitarist’s autobiography (co-written by Paul Rees), Steve Lukather: The Gospel According to Luke.

“I swear on the lives of my four children that every story is true,” he says, “Everything is in there. Well, maybe not everything. Let’s just say I can never run for office [laughs].”

At the time of this interview, Lukather was celebrating 40 years of Toto and, in a numerical coincidence, 40 million album sales worldwide. To mark the occasion, the band released 40 Trips Around the Sun (Sony/Legacy), a best-of album featuring remastered hits, as well as three previously unreleased tracks.

“Things have never been better for Toto,” says Lukather. “Everything we were told could never happen for us is now happening for us. And we don’t even have a manager!”

Why doesn’t Toto have a manager?

Well, I had to become Manager Guy. I have a staff, but Toto is my only client. I found out that classic-rock bands don’t need a manager just to call the agent, and say, “Book a tour,” and then take 15 percent.

All a band like us really needs is a tour manager, a production manager, good accounting, and a guy like me working with a great agent. And this new approach has really paid off.

We’ve always done well in Europe and Japan – that has kept us and all of our families alive – but the U.S. opened up for us in a huge way in the last few years, and that’s due to hard work. I mean, how many bands get a second chance in America?

Seeing Toto play at the Greek Theater in Los Angeles was amazing, because you’re the only band I can think of that has multiplatinum radio hits and takes things to the moon and back with extended solos.

We take pride in musically pushing things out there beyond what you might expect at a typical rock show, and we do give each member a moment to shine. I like to do my guitar spot within the context of a song.

I did “Red House” last year, even though Joe Bonamassa told me, “That’s the most over-played blues song in the world.” I said, “I used to do this one with dear Mike and Jeff Porcaro 25 years ago, so it has special meaning.”

Classic-rock bands don’t need a manager just to call the agent, and say, 'Book a tour,' and then take 15 percent

Steve Lukather

Eddie Van Halen, Mike Landau, and just about every other pro musician who had the night off was watching you that night. Is it nerve-wracking playing for all those heavies?

I didn’t even think about it. I just looked at my ten-year-old daughter. Seeing her with a backstage pass and a walkie-talkie like she’s out on the road with us cracked me up.

Plus, I’m at an age where I am starting to get relaxed about things, because I’m not in competition anymore. Sure, there was a little pressure that night, but those guys are my friends. If I were to make a mistake, those guys would laugh with me, not at me.

When you were putting together 40 Trips Around the Sun, was it weird diving into the raw sessions for songs recorded way back in the early and middle ’80s?

It was like playing with Jeff, Mike, and my 23-year-old self again. I discovered some things, as well. On “Spanish Sea,” for example, we added new parts to the basic tracks, including a new chorus that I wrote.

The solo, though, was from the original ’85 session, where Paich said to me, “Just play the melody.” So that’s what I did, and, man, it’s the simplest, most non-flashy thing I’ve ever played in my life.

You’re really good at telling a story with your guitar – like on your solo tune, “Song for Jeff.”

As I get older, I realize that ‘playing pretty’ is what I do best. I can’t be Mr. Fast Guy anymore – not that I ever truly was. There are a billion guitarists who can play unbelievably ripping guitar better than I can.

I’ve changed my whole thinking about guitar. I’d rather be more like David Gilmour than anybody else. On the new songs, for example, I really held back, played simple stuff, and tried not to play the obvious notes.

It’s hard to classify what kind of guitar player you are.

I know! I’m not metal, not jazz, not country, and not funk, but I do all of it. And I do it all in my own weird little way. I’m probably more rock than anything else, but that’s a broad description. My job as guitarist in Toto has always been to put teeth on the parts.

What was it that motivated you to play music in the first place?

It was never for fame. People might think, “I want to be famous.” No, you don’t. Even at my low level of fame, it’s the weirdest, most bizarre thing in the world. I had to build a gate in front of my house, because people would just show up at my door and freak out my six-year-old autistic son. But that’s nothing. I have movie-star friends who have TMZ parked in front of their houses. That’s famous.

I started doing music because I saw the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show. By today’s standards, it might seem fairly tame. They were in suits, and they didn’t even have long hair yet. But for me, it was like that part in The Wizard of Oz when life suddenly goes from black and white to color. My life changed in one moment. My goal was simply longevity – to have a long career – not to become famous.

I thought, I’m going to turn this energy into a positive. I’m going to prove Frank [Zappa] wrong. I’m going to make it, and someday he’ll know who I am

Steve Lukather

Was there ever a moment when your faith in guitar as a career choice was shaken?

I had a humiliating audition with Frank Zappa when I was 17. He embarrassed me in a room full of other guitar players, and I walked out of there trying not to cry.

I thought my career was over. But when I got home, I thought, I’m going to turn this energy into a positive. I’m going to prove Frank wrong. I’m going to make it, and someday he’ll know who I am.

So I played mad and practiced my ass off.

When I fell in love with the radio as a ten-year-old and started playing guitar, I loved the aggressive lead guitar on Boz Scaggs’ “Breakdown Dead Ahead.” I found out later that was played by you.

That was back when guitar solos weren’t shunned, but welcomed. I was playing solos on everybody’s shit. Boz really helped us – though we really helped him, too. If it weren’t for us, he would have just been a blues guitar player working through the scene.

Paich wrote him a bunch of hits, we played on those, and we sort of became the “L.A. sound,” if you will. Whether on purpose or not, Boz nurtured that sound, and soon we were all working all the time.

What was the biggest challenge of doing sessions back then?

Walking in with no rehearsal, having no idea what song you’re going to play on – or even what genre it’s going to be – and coming up with great parts. And you had to come with a good part quickly, because if you took too long, people would lose interest.

There was no editing your part together later in Pro Tools. Take the funky clean thing I came up with for Michael Jackson’s “Human Nature.” You’re in that room, you’ve never heard the song before, and Quincy Jones is two inches in front of your face going, “Come up with something funky for me right now.” That’s what we got paid for – not for reading the dots and playing what was written on the page, but for filling in the blanks where there was nothing on the page.

Being in that club of session players was great, because once you got in, you were in – if you got in. It was a hard club to get into. But while it took a little luck to get invited through that door the first time, it wasn’t luck to get asked back through that door a second time.

You played a pretty epic solo at the end of Don Henley’s “Dirty Laundry.”

That was a great session. Aside from punching in one spot where I made a little mistake, I think that was a first take. I was extra thrilled to be on that song because Joe Walsh – who I’m the biggest fan of – did the first solo.

Even if you don’t like my band’s music, I’m probably on more than one of the records in your collection

Steve Lukather

When I was in there, I had a whole room full of people staring me down. It was intense. Jeff Porcaro was looking at me like, “You’d better bring it, asshole.” That’s how it was. We all encouraged and pushed each other, and we all became successful.

Denny Tedesco made a cool documentary about the Wrecking Crew. You guys came a generation later. Someone should make a film about you guys.

Maybe someone will someday – probably after we’re all gone. We’re all over Thriller – the biggest record in history – and we get hardly any acknowledgement for it. Sometimes, I think we’re the Rodney Dangerfield of Rock. We get no respect [laughs].

I’m not saying, “Poor, pitiful me.” That would be ridiculous, because I’ve had an incredible career, and I’m very thankful for it. I just wish the critics would take us a little more seriously, rather than “that joke ‘Africa’ band.”

If you don’t like Toto, that’s cool. I don’t like everything, either. But even if you don’t like my band’s music, I’m probably on more than one of the records in your collection. You just don’t know it.

You’re an interesting blend of alpha dog and sensitive cat.

I’m a very sensitive cat. People don’t realize that about me, because I cover it up with humor, but this is an intense business to be in. It can really eat you up.

Some people think I have an attitude because I’m defensive about my band, but try taking shit for 40 years and not have a little edge. I don’t mean to be that way. I’m the nicest guy in the world until somebody draws first blood. Then, look out.

A lot of sessions are done in home studios now. Do you think a truly great album can be recorded that way?

Some artists can get away with making a record at home with GarageBand, and that’s cool, but you can’t make Sgt. Pepper, The Wall, or Dark Side of the Moon in your living room.

There’s something about the wood of a great studio, the million-dollar console, the expensive microphones, the really great engineer, and the really great musicians and songs that make a record a classic that will last forever.

That’s why the Beatles got two billion streams in their first year on Spotify without even trying. No one’s ever going to catch up with those numbers. The Beatles are our classical music.

Speaking of the Beatles, what’s it like to play with Ringo?

It’s hard to describe how much I love playing with Ringo. Having recorded with both him and Paul McCartney on two songs on Ringo’s Give More Love album is the greatest gift I’ve ever gotten. I can die now.

Above all, I just love Ringo as a person. He’s a beautiful cat. He has a vantage you can only have if you’ve been one of the most famous people on earth for 50 years. You’re not going to get better advice than what he offers.

Plus, there would be no rock-and-roll drums without Ringo. He put drum fills on the map. Just listen to “Tomorrow Never Knows.” I’ve been with him since 2012, and he’ll have to kill me to get rid of me.

There needs to be another Beatles

Steve Lukather

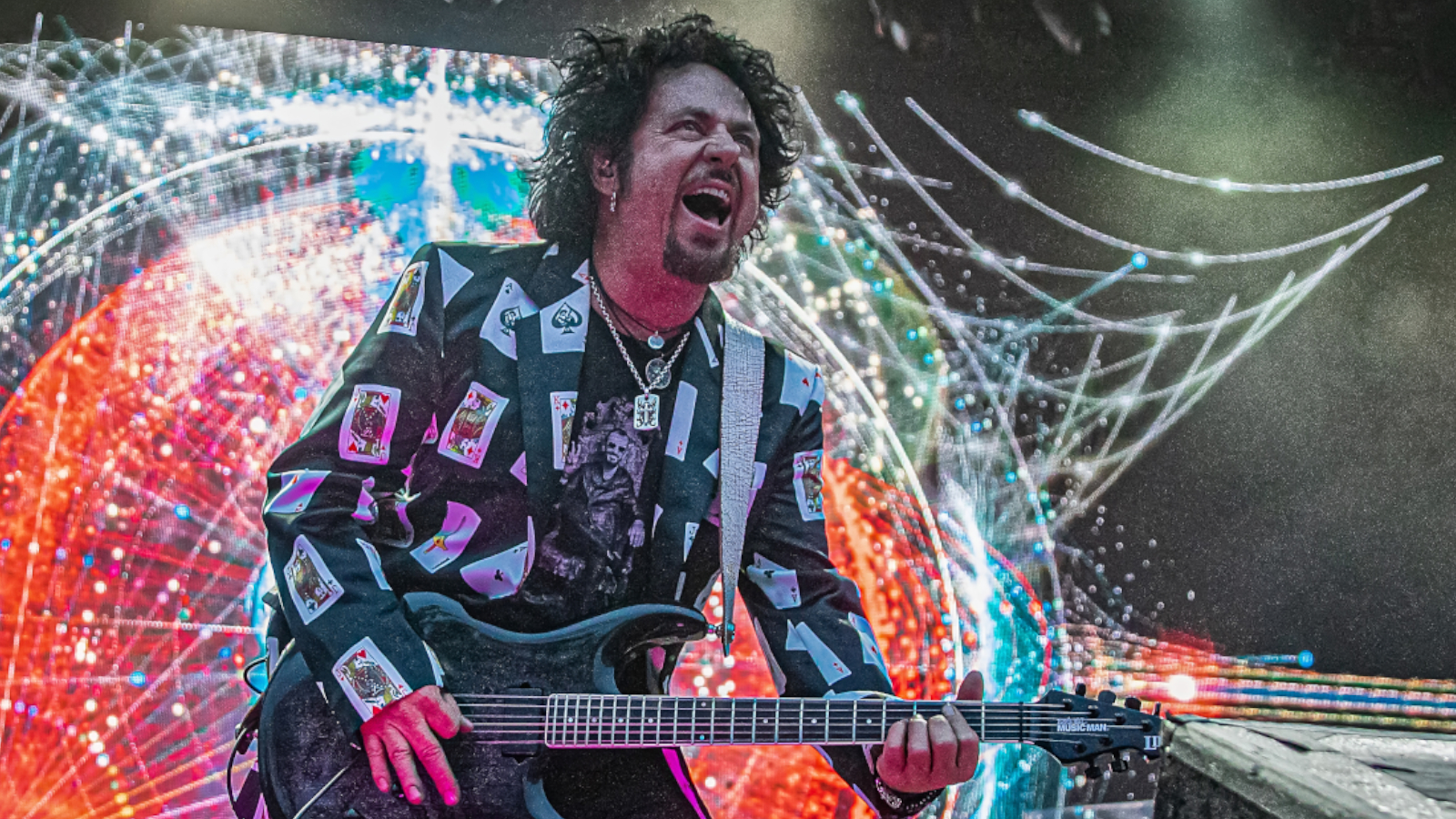

What’s your rig like these days?

It’s pretty straightforward. A few Ernie Ball Music Man guitars – including my signature models that are loaded with DiMarzio Transition pickups – and a couple of Bogner Ecstasy heads running in stereo.

I’m not even positive which pedals are in the loop these days, because my tech, Jon Gosnell, is so on top of things that I never have to think about the wiring. One pedal I use all the time, though, is The Luke. That’s my signature preamp boost from ToneConcepts. It works great as a distortion or a boost, or you can leave it on as a sort of mastering EQ for your rig.

I also use the Jam Wahcko wah and Waterfall chorus/vibrato. The Providence Anadime chorus is cool, too. No two choruses sound the same. Sadly, I’ll be forever known as the “Dytronics Tri-Stereo Chorus overuse guy,” because that title was somehow tattooed to me while I slept, due to one stupid guitar video that has followed me around forever like herpes [laughs].

There are TC Electronic and DigiTech delays, a MXR Uni-Vibe, an Xotic SP compressor, a Strymon blueSky reverb, and some other stuff on my pedalboard.

Lately, I’ve added Jeff Kollman’s signature Kollmanation pedal from T. Jauernig Electronics. I crank my Bogner up to about 8, kick on that pedal, and, amazingly, it doesn’t cause the tone to crash, as some overdrives will in that situation. It just makes things extra smooth.

Are you digging the next generation of guitarists?

Absolutely. Claims have been made lately that the electric guitar is dying, but I don’t believe it. They say sales are down, but I don’t believe that either. People are just buying stuff on eBay.

There are young kids who really get it. Sure, they start off playing the tricks and stuff – we all did that. But the cream rises to the top, and the best musicians are soon found out. I truly believe that Millennials are going rise up musically. It’s time. There needs to be an uprising of young 18-to-25-year-old kids who bring tunes that make us go, “Whoa!”

We need some amazing young kids who take a brave political, social, and musical stand, and bring on something positive. There needs to be another Beatles.

Order Toto's 40 Trips Around the Sun here.

Whether he’s interviewing great guitarists for Guitar Player magazine or on his respected podcast, No Guitar Is Safe – “The guitar show where guitar heroes plug in” – Jude Gold has been a passionate guitar journalist since 2001, when he became a full-time Guitar Player staff editor. In 2012, Jude became lead guitarist for iconic rock band Jefferson Starship, yet still has, in his role as Los Angeles Editor, continued to contribute regularly to all things Guitar Player. Watch Jude play guitar here.