Mike Campbell is what you might call a “band guy.” Currently, he’s a member of two outfits - Fleetwood Mac, which he joined in 2018, and his own act, the Dirty Knobs, a group he formed as a side project more than a dozen years ago and which is readying its debut album.

If he had more time in his schedule, he’d probably join a third band. “It’s just the way I am,” the veteran guitarist says. “Some guys join a band and use it as a springboard to go solo. I never saw the point in that. I like the idea of being in a gang and having your buddies around.” He chuckles, then adds, “It’s less lonely that way.”

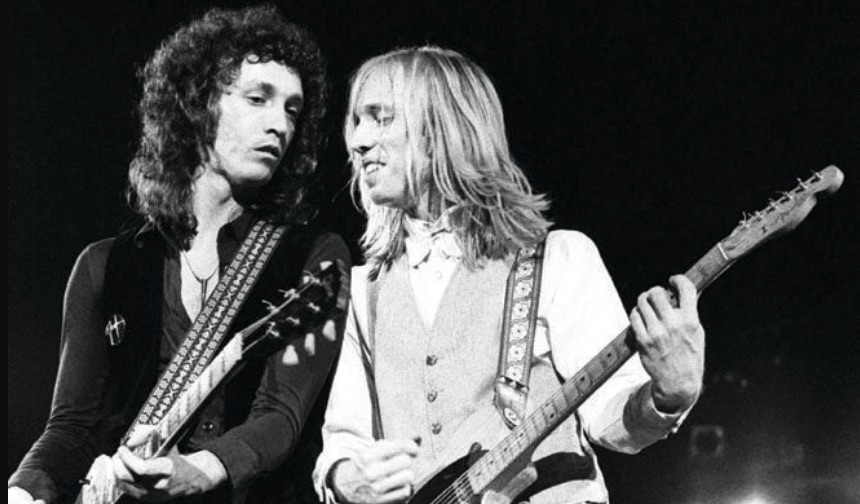

For more than 40 years, Campbell was the ace lead guitarist and sometime co-songwriter of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, and if fate had turned out differently he’d still be making music with his lifelong friend. “I’m still going through grief and processing the fact that Tom is no longer here,” he says. “I treasure the memories of what we did together.”

The Florida-born Campbell first hooked up with Petty in the early ’70s in a Gainesville-based group called Mudcrutch. The band would ultimately relocate to Los Angeles, sign a record deal and morph into Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. Before then, Campbell was playing around Gainesville in a band called Dead or Alive, which he remembers as being “pretty good.”

“We got gigs, so that put us ahead of most local bands,” he says. “We played around the college for free and did some women’s clubs here and there. ‘Oh, the women’s club wants to give us 200 bucks? No problem!’ That was big money to us in those days.”

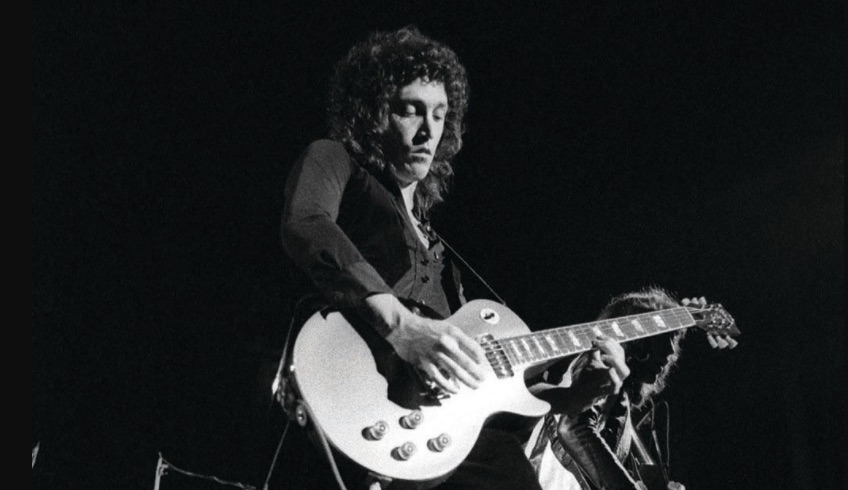

Beyond the occasional $200, Dead or Alive offered Campbell a chance to hone his craft onstage. He’d been playing guitar for only a few years, starting out on a Harmony acoustic before moving to a $60 Goya electric that his father bought in Okinawa while serving in the U.S. Air Force.

By slowing down records on his phonograph and learning the licks of his two biggest inspirations, Mike Bloomfield and Jerry Garcia, Campbell took his guitar playing to a decent level of proficiency, but he asserts that he didn’t find his own voice as a player until he started gigging.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Dead or Alive was my first band and my first real chance to play live,” he says. “We did a lot of 10-minute jams. This was an important time for me. I had learned the basics, but now I could get out there and put it together. I think with me, I got to a point where I was like, ‘I know what I’m doing. People are responding to it and I’m inspired by it.’

So that pushed me to get better, to explore the nuances of playing. Guitarists know what I’m talking about. Once you go from nothing to ‘pretty good,’ you need that opportunity to go to another level. That’s what happened with me. Playing live, I was able to establish what I was, and I stayed with it the rest of my life.”

As for that Goya guitar, Campbell continued playing it for his first few years with Petty, until the singer suggested quite pointedly, “You should get a better guitar.” Campbell bought a Gibson Firebird and, thanks to a gift from a friend, acquired a Fender Strat.

He gave the Goya away and lost track of it, but after mentioning the guitar in an interview 15 years ago, he was stunned when somebody from a Tom Petty fan club who had read the piece found the instrument and mailed it to him for his birthday. “Talk about a sweet gesture,” Campbell marvels. “We’ve always had the greatest fans.”

So let’s talk about how you joined Mudcrutch in the early 1970s. Did you have to audition for Tom to get the gig?

I don’t know if you’d call it an audition. My bass player left for Hawaii to be a surfer, so it was me and Randall Marsh, my drummer, left over. We had seen this band called Mudcrutch playing in the park. They were doing a Burrito Brothers–type thing, and they had harmonies and three-minute songs. I was impressed.

I saw a sign that said they were looking for a drummer, so I told Randall he should audition. He called them up and they came to this house that he and I were sharing.

I was in the back room, and as it turned out their guitar player had quit. So Randall said, “Hey, my friend in the back room is a guitar player.” So I came out - I had short hair and cut-off jeans - and they looked at me and said, “Oh, fuck. This guy’s a loser.” I had my little Goya guitar, and they said, “What do you know?” So I said, “How about ‘Johnny B. Goode’?”

We played that, and when we got to the end, Tom said, “I don’t know who you are, but you’re in my band forever.” I told them I was in college because I didn’t want to go to Vietnam. Tom goes, “Don’t worry, we’ll take care of that. You’re going to grow your hair out, and you’re going to be great. You’re in the band.”

Tom saw something in you, but what did you see in him?

He was writing songs. He showed us some, and I said, “I write, too.” I showed him something I had, and I think maybe he saw me as a potential writing partner. We didn’t really discuss it that much. It was just one of those destiny things - a chance meeting that changed our lives. We became fast friends, and that’s what we were till the end.

Fast forward a few years to when Mudcrutch became Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. You guys didn’t have immediate success in the States. Britain took a shine to you first. They called you “new wave.”

Yeah, that was kind of exciting. We put our record out in the States. It got a little airplay in San Francisco and Boston, but nothing happened. Somehow, the label booked us a tour in England, which was just a dream come true, to go to England to be able to play music. They picked up on what we were doing, and that energy spread back over to the States, and then things started to happen for us.

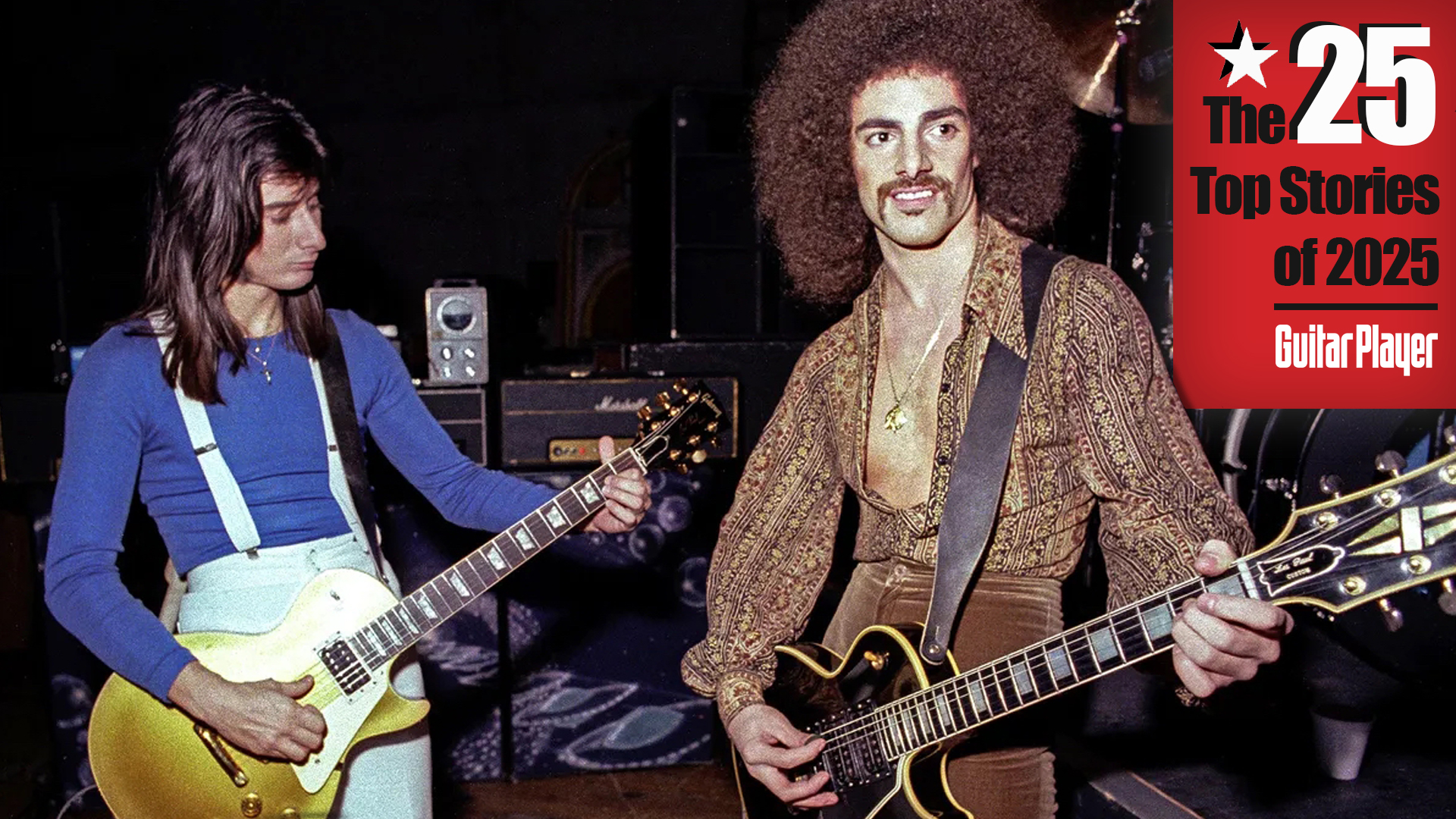

When would you say Tom and you started to perfect that chiming, dual-guitar sound?

It started on the first record. I saw a ’64 Strat for $200 in a music store, but I couldn’t afford it. Then a friend of mine got an insurance settlement from an automobile accident, and she said, “What if I buy that guitar for you?” I said, “Okay.” So she bought it for me right when Tom switched to guitar.

I let him play that, and by then I had gotten a ’50s Broadcaster and a Les Paul. We were doing the first record, and we loved George Harrison and Roger McGuinn. We said, “We should get a 12-string.” I got one for 120 bucks, and that’s the guitar on the Damn the Torpedoes cover.

On the second album, on songs like “Listen to Her Heart,” we were using the 12-string. The sound was developing, and eventually it became a go-to sound for us.

Was there a moment when you both realized, “The 12-string changes our sound, but we’re going for it”?

That happened on “American Girl,” which is interesting because we didn’t have a 12-string at the time. We wanted that sound, however, so I figured out how to play octaves on my Broadcaster to get a 12-string sound.

We cut that track, and it was like an epiphany. We found out what we were. We found a harmonic foundation for how we wanted to sound, and it worked for our personality and Tom’s voice. In my view, that’s when we became the Heartbreakers.

As a songwriter, you certainly made your mark with “Refugee.”

That was a good one. [laughs]

When you would present music to Tom, did you show him everything you had, or did you show him only what you thought was really good?

I didn’t know what was really good. I would just give him whatever I was working on and let him pick what he liked. Around the second album or so, I got a TEAC four-track, and I began working on that at home, putting music together, overdubbing and making my sound. I loved it. Tom would hear things and get inspired.

I remember our first producer, Denny Cordell, came over and heard some of my things. He said, “If you develop what you’re doing here, you’ll be a millionaire someday.” I went after it. By the time we hit “Refugee” and “Here Comes My Girl,” I was getting better at coming up with ideas and then putting one extra guitar on it. I’d add bass or whatever and make it sound like a record.

Jimmy Iovine came into the picture on the third album. Tom had written “Refugee” and “Here Comes My Girl” with me. When Jimmy heard those two songs, he said, “That’s all we need. I don’t care what the rest of the record is. Pick those two songs and we’ll be fine.”

Did you guys click with Jimmy Iovine right away?

The first record we did with Jimmy was kind of hard. We got him in because we liked the sound of the Patti Smith record “Because the Night.” We wanted a bigger sound.

Jimmy came with his engineer, Shelly Yakus, and we really worked hard to get the snare drum to sound right, the kick drum to sound right, get the guitars to sound there. On “Refugee,” we worked on the guitar sound for months. It wasn’t always fun, but it was still a labor of love.

You’re often cited for your exquisite, tasteful playing - the right note at the right time, lyrical solos… Did Tom ever show you things he wanted you to play?

Not at all. He always trusted me to come up with stuff. Tom would bring in a song, and it would be bare bones - sometimes on guitar or piano. He’d just play and let us join in. I remember with “Breakdown,” we cut the track one night, but it didn’t have an intro. I had an idea to sort it out later, so we cut the track and I noodled along with a slide. It was all off the top of my head.

I went home and went to bed, and about two hours later, the phone rings. It’s Tom going, “I’m down here at the studio with Dwight Twilley and we’re listening to that track.” He said, “There’s a lick you played at the end of the song that we want to put at the beginning.”

So I got up, went back down to the studio, and I listened to it and learned it without the slide. We went back to the top of the song and I played that bit. It became kind of a signature of the song. That’s how we would work. He would just let me do what I wanted to do, and either he liked it or he didn’t like it. But he usually liked it.

Did you and Tom ever discuss guitar configurations? I’ve never seen you both play the same guitars at the same time.

That was Tom’s stage rule, too. That started when I gave him my Strat. He would be playing rhythm and singing, so I couldn’t go for something with a thin sound. I’d go for a Les Paul or a Rickenbacker - whatever the song called for.

There wasn’t much discussion about it. Usually he would just say, “What do you think?” And I’d go, “Let’s try this.” A lot of it was instinct - or luck.

Years before you joined Fleetwood Mac, you worked with Stevie Nicks on “Stop Dragging My Heart Around” and on her Bella Donna album. She once said that she wanted to be in the Heartbreakers.

God bless her, she did. But there’s no girls in the Heartbreakers. [laughs]

Were those sessions with Stevie fun?

They were, and of course, she became a good friend. By that time, we were comfortable working with Jimmy Iovine. We had “Stop Dragging My Heart Around,” and Jimmy, in his wisdom, said, “This would be great as a duet,” so Stevie ended up singing over our track.

As I understand it, you originally played your demo for “The Boys of Summer” to Tom for the Heartbreakers to record.

Yeah. I had a LinnDrum, and I started messing around and put the track together. I had the music all laid out, but I had a different chorus at the time - it wasn’t as good as the one everybody knows. I played it for Tom and Jimmy Iovine, and it got to the chorus and Jimmy goes, “Oh, that sounds a little jazzy.” He was right. So Tom passed on it.

But a week later, Jimmy called and said, “Don Henley is looking for some music. How about that track you played us?” And I said, “Okay.” I went back and listened to it, and I thought, Before I give it to Don, I think I’ll change the chords in the chorus and make it a little easier to sing to. So I put the new chords in the chorus and sent Don the four-track demo. He loved it, and he wrote those words and melody over it.

All of those beautiful, cascading guitar licks - were they on the demo?

All those bits were there. Don would have used my demo, but the song was in the wrong key for him to sing. That demo was just me having fun and doing stuff off the top of my head. So I had to relearn those parts to re-create them for the final track. It was a struggle, but I got it.

After the song became a huge hit, did Tom kind of wish that he had done it?

We were in the studio once, and we went out to the car with a cassette to listen to the mix. As we were about to put the tape in, I turned the radio on and “Boys of Summer” came on. Tom said, “Oh, I wish I would have had the presence of mind not to let that one get away.”

In the Heartbreakers, you worked with different rhythm sections over the years. Did you adapt to their styles, or vice versa?

It was all about following Tom. It was like, “Here’s the song. Play a beat to this. Play something simple to not get in the way of these chords and this vocal.” And that’s pretty much what it was.

You’ve done a lot of outside sessions. When somebody asks you to play on their record, what are they looking for?

They’re usually looking for the Heartbreakers sound, typically. I’ve never really asked what they were looking for, but I guess if they call me, it was because they’ve heard what I’ve done. I have to like the artist, I have to like the song, and I have to have the time to do it.

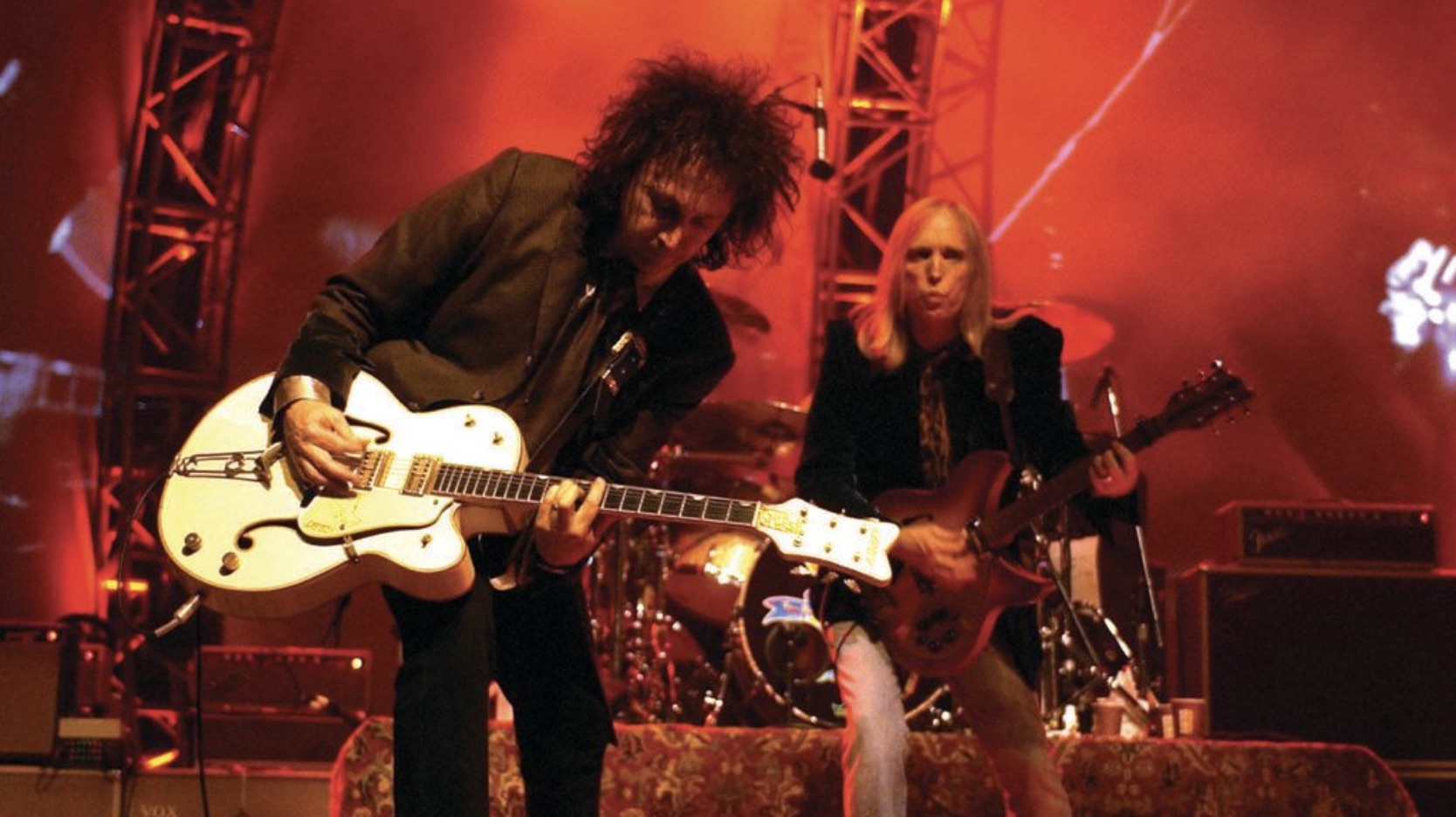

When you joined Fleetwood Mac, was it supposed to be just you on guitar, or was it already decided that the guitarists would be you and Neil Finn?

They didn’t have Neil at first. Mick Fleetwood called me on my birthday and said, “We’d like you to join the band. Are you interested?” Lindsey had just left. I said, “Give me 24 hours to think about it.” I thought about it quite a bit - what it would mean to me, how it would feel filling in someone else’s shoes.

I decided that it was a challenge I wanted to take. I love the band, I love Stevie, and I love that rhythm section. They have one of the best rhythm sections in rock history, and it’s probably the only one still together.

Mick told me I didn’t have to audition, that I was in the band, so we had a meeting and they said that they wanted to have a singer because a lot of the songs have a male voice. I don’t know who came up with Neil, but I was right onboard. We called him up, he came out, and it worked right away. He and I get along great. He plays mostly rhythm and sings, and I play the parts.

You guys did a major tour in 2018 and ’19. What’s the plan moving forward?

Yeah, that was the longest tour I’ve done in my life. We went around the world for about a year and a half. Everybody was really tired at the end, so we agreed that’s probably the last time we want to do something so extensive.

I’ve got the Dirty Knobs now for a while, so I think we’ll get back to Fleetwood Mac in a year, year and a half. Stevie wants to do a movie and probably some solo touring. At that point, if there’s a handful of gigs that sound good to us, we’ll get back together and do them. That’s how it was left.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.