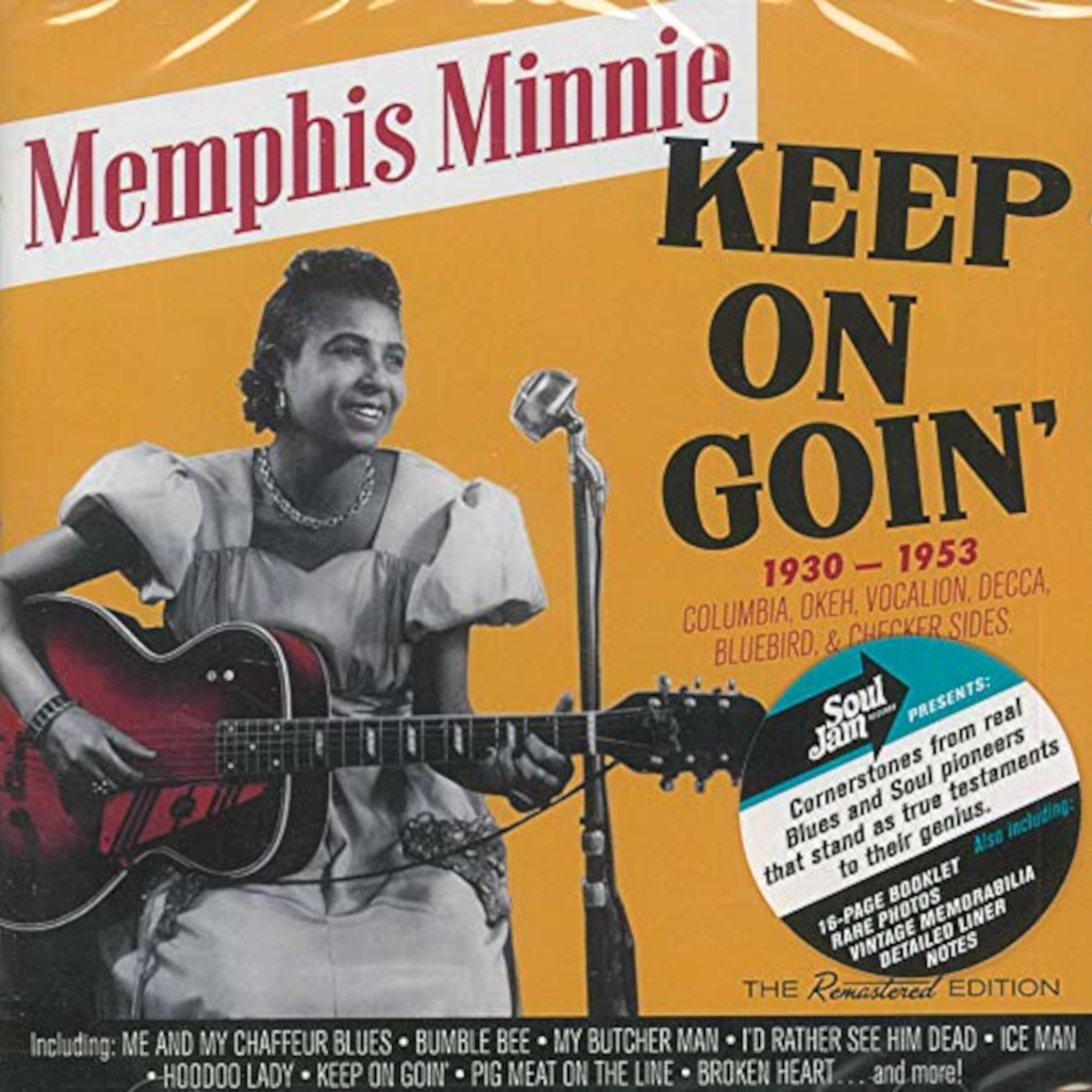

Prolific, Confessional and a No-Bullsh*t Character: How Memphis Minnie Became One of the Most Incendiary Guitarists of Her Day

The renegade star's professional career in blues is matched by no other female musician, and by very few men

You can’t talk about the leading lights of blues without mentioning Memphis Minnie.

An extremely prolific, confessional recording artist and a no-bullshit character, Minnie had a tough life, which she skillfully poured into her music.

She chewed tobacco all the time, even while singing or playing the guitar

Homesick James

Noted American blues guitar slide master Homesick James, “She chewed tobacco all the time, even while singing or playing the guitar, and always had a cup at hand in case she wanted to spit.”

Born Lizzie Douglas, in Louisiana in 1897, she ran away while in her teens to Memphis, where she played guitar and sang on street corners, supplementing her income with prostitution when she had to.

For a stint from 1916 to 1920, she toured the South with the Ringling Brothers Circus. But it was when she started performing with her first husband, Joe McCoy, in 1929, that her career took off.

Columbia Records snapped the couple up and renamed them Kansas Joe and Memphis Minnie, which is how they performed until their divorce in 1935.

Her professional career in blues is matched by no other female musician, and by very few men

By then, Minnie was an established figure on the tour scene, one who could comfortably hold her own, and so she began experimenting with different styles.

Minnie was 32 when she made her first recordings with McCoy. She was a contemporary of Delta blues guitarist Tommy Johnson and just a few years older than Son House and Skip James.

More than 20 years later, when all those men were largely forgotten, Minnie was still drawing audiences in clubs and still making records.

Her professional career in blues is matched by no other female musician, and by very few men. How she managed that is clear on the 2016 compilation Keep On Going: 1930–1953.

Listen to her intricate guitar duets with McCoy from the early ’30s; the small-band tracks from the later part of that decade; her plugged-in 1941 recordings with next-husband Ernest “Little Son Joe” Lawlars, such as her hit “Me and My Chauffeur Blues”; and the still punchy music she made in the ’50s such as “Kissing in the Dark” and “Broken Heart.”

Minnie had a tough life, which she skillfully poured into her music

What Minnie had was adaptability. Like Big Bill Broonzy – who recalled her beating him in a cutting contest in a Chicago nightclub in 1933 – she heard how the sounds and themes of the blues were changing with the times and she kept pace with them.

Johnson, House and James were greats, but this kind of musical re-invention would have been beyond them.

During the ’60s, Minnie reaped the benefits of the young generation’s renewed interest in blues, with the new wave of players and enthusiasts recognizing her role in laying crucial foundations of the genre.

In 1971, Led Zeppelin reworked her song “When the Levee Breaks” into a bigger and bolder version thanks in no small part to John Bonham’s huge drum sound. But the grounding hoodoo at the heart of it was all Minnie.

Order Memphis Minnie’s Keep On Going: 1930-1953 here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Guitar Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful guitar publication for passionate guitarists and active musicians of all ages. Guitar Player magazine is published 13 times a year in print and digital formats. The magazine was established in 1967 and is the world's oldest guitar magazine. When "Guitar Player Staff" is credited as the author, it's usually because more than one author on the team has created the story.

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue

"Get off the stage!" The time Carlos Santana picked a fight with Kiss bassist Gene Simmons and caused one of the guitar world's strangest feuds