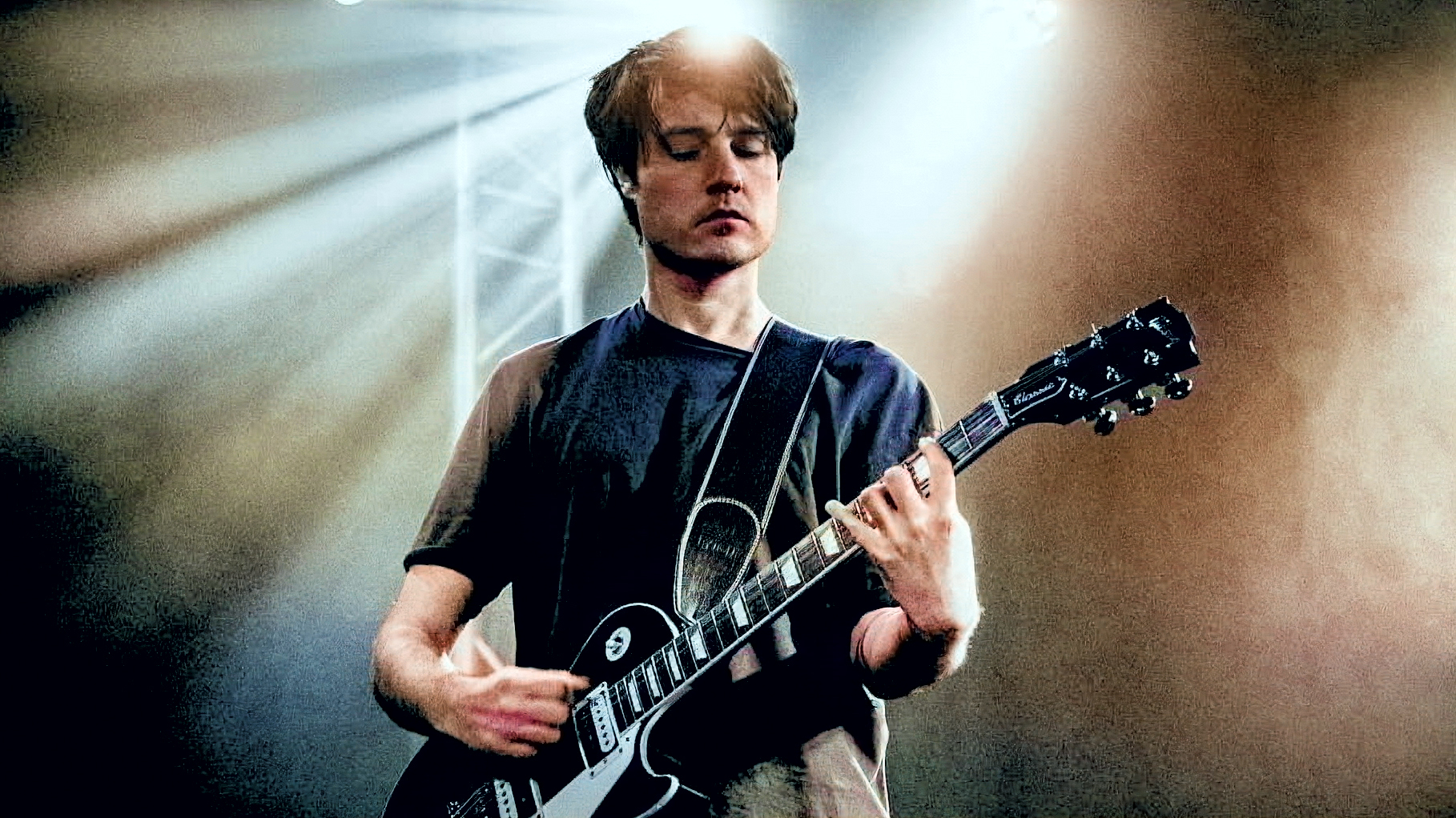

“I got into my bunk on the bus, but there was a guitar case in my way. I was like, ‘What is this doing here?’ ” Nada Surf’s Matthew Caws on vintage Gibsons, Ric Ocasek’s gift and scoring their second hit after 28 years

Twenty-eight years after they scored a bona fide hit with the indie rock classic “Popular,” Nada Surf have finally stormed the Billboard charts again, this time with “In Front of Me Now,” the breezy and wistful power pop lead single from the group’s 10th studio album, Moon Mirror. For guitarist and frontman Matthew Caws, it’s an achievement that comes with a dubious distinction: No longer can the band be packaged on various “one-hit wonder” compilations.

“In truth, we’ll see if we ever outrun that definition,” he tells Guitar Player via Zoom from his home in Cambridge, England. “I feel that glue has been set for such a long time. It’s fine, really. It was nice to have early recognition. It was better than having to struggle for years.”

Like most songs in the Nada Surf canon, “In Front of Me Now” is witty and sophisticated ear candy, and its hooks waste little time scoring knockout blows. But there’s a salient message in the track that Caws landed on when he realized that multi-tasking had started to wreak on his life and that he needed to focus on one thing at a time. “It’s my impulse to do everything at once, but the results aren’t always so great,” he explains. “I haven’t gotten to where I want to be yet, so it’s kind of an aspirational song.”

Throughout most of the band’s 32-year existence, Nada Surf have maintained the same lineup of Caws, bassist Daniel Lorca and drummer Ira Elliot (on Moon Mirror, they’re joined by keyboardist Louis Lino). But the one-time Brooklyn-based outfit is now spread out at various locations on both sides of the Atlantic (Lorca lives in Ibiza, Spain; Elliot in Sarasota, Florida; and Lino in Austin, Texas), which, according to Caws is “logistically and financially a terrible idea. However, we’re still together, and part of us still being together is that there haven't been any kind of rules like that. Live where you want to live, be with who you want to be with. It’s definitely helped us stay together.”

Critics have described the band’s sound in various ways: indie rock, power pop, alt rock. The long and the short of it is, your songs rock, but they’re also very poppy. When you’re writing or recording, do you conceptualize them to inhabit any particular sonic lane?

There’s definitely no conceptualizing, but I agree with what you're saying. I naturally do what I do, and it’s this in-between of poppy and rocky. It probably all stems from back when my best friend’s older brother sat me and my friend down and said, “You wanna listen to some music?”

We sat on his bed and he played the Ramones’ Rocket to Russia, the Velvet Underground’s Loaded and the Talking Heads’ Remain in Light. That was a big moment. Then, a year later, a friend gave me a tape of Tommy, and I started buying all the old Who records. I’m sure there’s a way to pick out all those bits in what we do. I like catchy and strong.

“Catchy and strong.” That also reminds me of Cheap Trick.

Totally. They feed off each other. If something strong makes you feel ecstatic, that feeds into wanting to find an exciting melody.

Production-wise, do you have any sort of formula or process you follow?

We’ll track together, and then we’ll replace anything that doesn’t feel right. I'm a little bit addicted to layering. I love records where you can hear the simple discrete parts. I mean, even on Yes albums — there’s four players, four parts. I admire that. I’m also hooked on double tracking things, like vocals.

But it all starts with everybody playing together in the same room.

Right. We stand in the same room, but the amps are in separate rooms.

Your basic guitar track — is it very overdriven?

It's right down the middle. It’s hot, not clean, but it’s now super power. Lately, I start with my go-to amp, a Fender Deluxe Reverb with a pedal in front — it’s a French pedal that’s like a Klon clone.

In all, how many guitars do you generally layer?

A typical song will at least have two or three in the verse and then one or two more in the chorus. That’s not every song, but it’s sort of a standard. I don’t know when that standard moved in developed — the really crunchy chorus. Did Cheap Trick invent that? I don’t know.

Am I hearing an E-Bow throughout much of “In Front of Me Now”?

No, that’s Louie Lino playing sort of a Greg Hawks-ish melody line. It’s a great mystery sound.

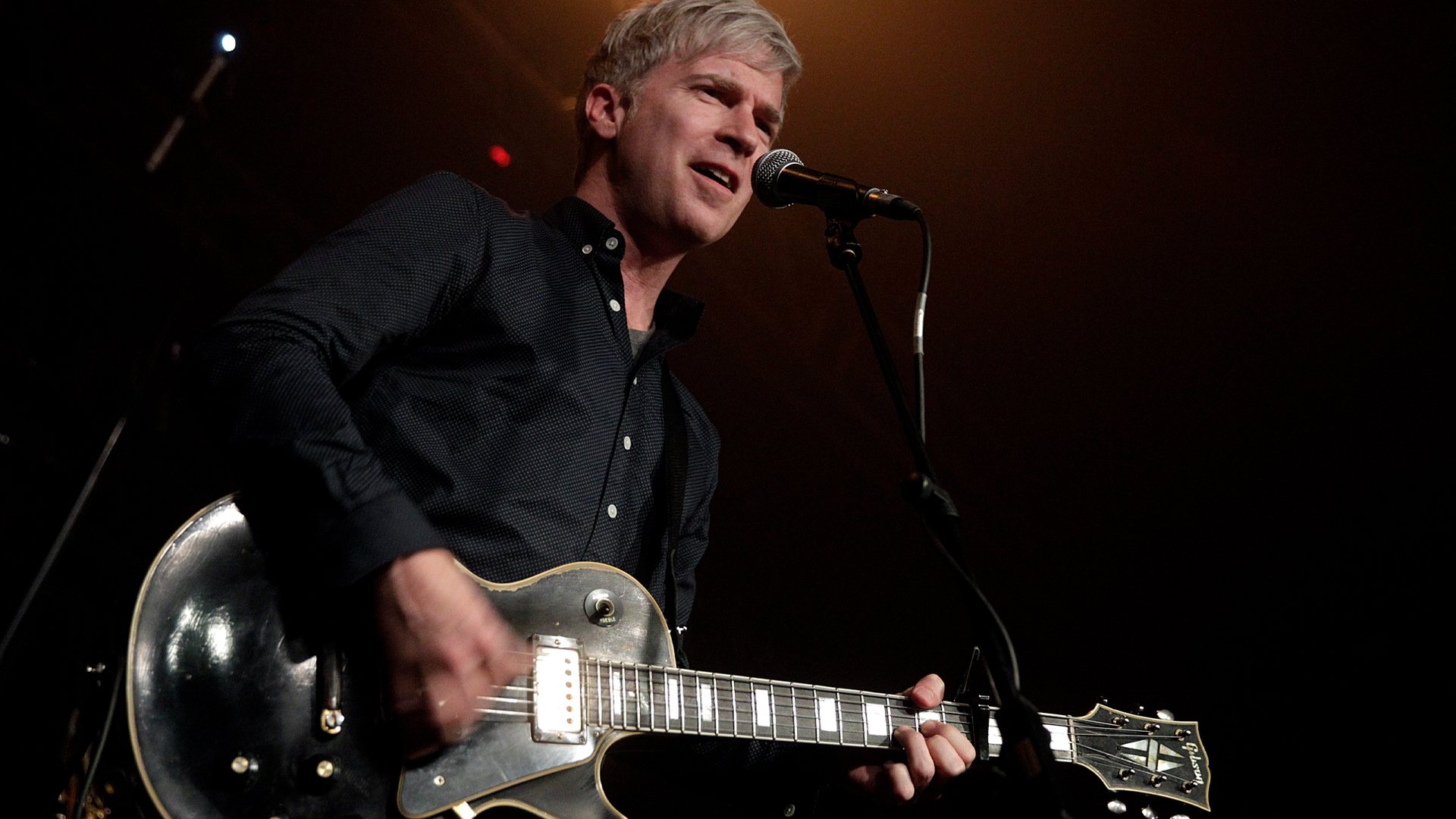

On a Cars-related note, what kind of musical lessons did you learn from working with Ric Ocasek on your first album?

The biggest lesson was learning not to worry about which take of a song was perfect. Ric’s attitude was to record a song three times, listen to the takes and then say, “Which one is the best?” He looked for an exciting performance, but he didn’t worry if it had hiccups in it. Also, when double- and triple-tracking guitars, he was really picky about them being super tight.

Honestly, the biggest thing was his support and that he liked us. For the rest of my life, I'll be so grateful that he liked us, and he expressed that by calling back when I'd give him a tape. He’d say that he really liked it, and he’d offer to record the songs again for cheap. And then he'd produce them if we ever wanted to rerecord them. He was so supportive, and getting that from somebody I really admired was an early boost of confidence that probably helped us continue to go for it.

Elektra wanted a big follow-up to “Popular,” and when they didn’t get it, they dropped the band. How difficult was that period for you? Was it hard to keep going?

My feelings were hurt. It didn't feel good. I remember the label saying, “We're not sure this record has a single. Maybe you should record some covers and stuff,” but It never occurred to me that they wouldn't put it out. The album was released in Europe, and we went there and did promo and some gigs. We knew it would work.

And then something great happened. This band from Kansas called Ultimate Fakebook that our new manager, Ben Weber, was managing, took us out on a short little tour, and they were plugged into the all-ages, unofficial-venue, sell-a-lot-of-merch kind of world that we didn’t really know. Our first manager didn’t understand that. We saw that it was much better to fill a small room than half of a big room. It was energizing.

For years, you’ve used a ’69 Les Paul Custom and a ’69 Tele. Were those your main guitars on the album?

Yeah. The Tele has this MiCawber bridge made by Armadillo. I know it’s sacrilegious for Fender people, but the Tele has a Seymour Duncan ‘59 humbucker. Plus, there’s a 1966 Vox Teardrop 12-string — I had sold it but got it back. I also used a 1960 Gibson J-150 acoustic. I saw it in a store in Dublin, but I couldn’t afford it. I mentioned it to Daniel, our bass player, and the later that night, at two in the morning, I got into my bunk on the bus, but there was something in my way — it was a guitar case. I was like, “What is this doing here?” He’d bought me the guitar!

That’s incredible.

Yeah. I never liked the pickguard, and I noticed that James Taylor had his removed on his J-150, so I had mine removed a couple of months ago. I’m so happy with it.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.